Censorship in Venezuela

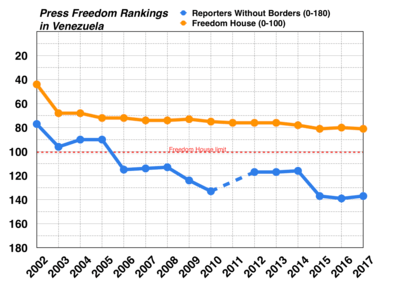

Sources: Freedom House's Freedom of the Press and Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index

Note: Freedom House rank limited to 100 (worst)

| Part of a series on | ||

| Censorship by country | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Countries | ||

|

|

||

| See also | ||

Censorship in Venezuela refers to all actions which can be considered as suppression in speech in the country. Reporters Without Borders ranked Venezuela 137th out of 180 countries in its World Press Freedom Index 2015[1] and classified Venezuela's freedom of information in the "difficult situation" level.[2]

The Constitution of Venezuela says that freedom of expression and press freedom are protected. Article 57 states that "Everyone has the right to freely express his or her thoughts, ideas or opinions orally, in writing or by any other form of expression, and to use for such purpose any means of communication and diffusion, and no censorship shall be established." It also states that "Censorship restricting the ability of public officials to report on matters for which they are responsible is prohibited." According to Article 58, "Everyone has the right to timely, truthful and impartial information, without censorship..."[3]

Human Rights Watch said that during "the leadership of President Chávez and now President Maduro, the accumulation of power in the executive branch and the erosion of human rights guarantees have enabled the government to intimidate, censor, and prosecute its critics" and reported that broadcasters may be censored if they criticize the government.[4][5]

Reporters Without Borders said that the media in Venezuela is "almost entirely dominated by the government and its obligatory announcements, called cadenas.[6]

In 1998, independent television represented 88% of the 24 national television channels while the other 12% of channels were controlled by the Venezuelan government. By 2014, there were 105 national television channels with only 48 channels, or 46%, representing independent media while the Venezuelan government and the "communitarian channels" it funded accounted for 54% of channels, or the 57 remaining channels.[7] Freedom House has also stated that there is "systematic self-censorship" encouraged toward the remaining private media due to pressure by the Venezuelan government.[8]

Resource drains and media buyouts

Both President Chávez and President Maduro would pressure media organizations until they failed by preventing them from acquiring necessary resources. The Venezuelan government would manipulate foreign exchange rates for media organizations so that they could no longer import their resources or fine them heavily. The government would then use a front company to give the troubled organization a "generous" offer to purchase the company. Following the buyout, the front company would promise that the staff would not change but would slowly release them and change their coverage to be in favor of the Venezuelan government.[9]

Soon after Nicolas Maduro became President of Venezuela, El Universal, Globovisión and Últimas Noticias, three of some of the largest Venezuelan media organizations, were sold to owners that were sympathetic to the Venezuelan government.[10][11][12][13] Shortly after, employees of the affected media organizations began to resign, some supposedly due to censorship enforced by the new owners of the organizations.[14][15]

Following nearly 83 years of printing newspapers to the Venezuelan public, on 17 March 2016, the newspaper released its final edition of its physical newspaper, discontinuing the use of printed material. On its final front-page editorial, El Carabobeño explained that the government agency that has the responsibility of distributing newsprint had not attempted to sell the necessary resources to the newspaper.[16]

Following the election of President Maduro, 55 newspapers in Venezuela stopped circulation due to difficulties and government censorship between 2013 and 2018.[17]

Radio censorship

In 2001, there were 500 independent radio stations in Venezuela and only 1 state-sanctioned station.[18]

On August 1 of 2009, Diosdado Cabello, then director of CONATEL, ordered the intervention of 32 radio and 2 television stations, decision that received the name of Radiocide.

In 2017, the Maduro government removed 46 radio stations from the air according to the National Union of Workers of the Press.[19]

Television censorship

In 2008, Reporters Without Borders reported that following "years of 'media war,' Hugo Chavez and his government took control of almost the entire broadcast sector".[20]

During the 2014 Venezuelan protests, Colombian news channel NTN24 was taken off the air by CONATEL (the Venezuelan government agency appointed for the regulation, supervision and control over telecommunications) for "promoting violence".[21] President Maduro then denounced the Agence France-Presse (AFP) for manipulating information about the protests.[22][23] After an opposition Twitter campaign asked participants of the Oscar ceremony to speak out in support of them, for the first time in decades, private television channel Venevisión did not show The Oscars, where Jared Leto showed solidarity with the opposition "dreamers" when he won his award.[24]

When a TV series portraying Hugo Chávez titled El Comandante was to be aired for the first time, the Bolivarian government censored the episode with President Maduro saying that El Comandante was "a series to try to disfigure a true leader and a Latin American and world hero", while the National Commission of Telecommunications tweeted to Venezuelans that they should inform the commission "if any cable operator insults the legacy of Hugo Chavez transmitting the series ‘El Comandante,’ ... #NobodySpeaksIllOfChavezHere".[25]

During the 2017 Venezuelan protests, CNN en Español was taken off air by CONATEL. On August 24 CONATEL blocked Caracol TV and RCN Colombia.[26] According to the National Union of Workers of the Press, three television channels were removed in the months up to August 2017.[19]

Internet censorship

Freedom House[27]

In the Freedom on the Net 2014 report by Freedom House, Venezuela's internet was ranked as "partly free", with the report stating that social media, apps, political and social content had been blocked, while also noting that bloggers and Internet users had been arrested.[27] In 2014, Reporters Without Borders originally stated that Venezuela did not fit the categories of either "surveillance", "censorship", "imprisonment" or "disinformation"[28] but later warned of "rising censorship in Venezuela's Internet service, including several websites and social networks facing shutdowns". They condemned actions performed by the National Commission of Telecommunications (Conatel) after Conatel restricted access to websites with the unofficial market rate and "demanded social networks, particularly Twitter, to filter images related to protests taking place in Venezuela against the government".[29] The Venezuelan government published a statement replying to censorship allegations on Twitter and with images on Twitter, implying that it was a technical problem.[30]

Previous research conducted in 2011 by the OpenNet Initiative report said that Internet censorship in Venezuela was "non-existent"[31] In 2012, OpenNet Initiative found no evidence of Internet filtering in the political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas.[31][32] Recently, OpenNet Initiative stated that actions by the Venezuelan government suggests that the government promotes self-censorship, information control and that changes in Venezuelan law may target websites in government information control efforts.[33]

In May 2015, Juan Carlos Alemán, a Venezuelan official speaking on television, announced that the Venezuelan government was in the process of removing the use of servers from Google and Mozilla and using Venezuelan satellites in order to have more control over the internet of Venezuelans.[34]

By 2017, Freedom House declared in its Freedom on the Net 2017 report that Venezuela's internet was ranked as "not free", citing the blockage of social media applications, political content being blocked, attacks of online reports by law enforcement and the arrests of internet users.[35] Since late-2017, the Venezuelan government censored the website El Pitazo, blocking it with DNS methods.[36]

Following the 2018 Venezuelan presidential election, the website for El Nacional was sanctioned by the state-run CONATEL on 22 May 2018, with the violation of Article 27 of the Social Responsibility in Radio, Television and Electronic Media being cited by the Venezuelan government.[37]

Law

In December 2004, the government of Venezuela approved a law named "Social Responsibility in Radio, Television and Electronic Media" (Ley de Responsabilidad Social en Radio, Televisión y Medios Electrónicos). The law is intended to exercise control over content that could "entice felonies", "create social distress", or "question the legitimate constituted authority". The law indicates that the website's owners will be responsible for any information and contents published, and that they will have to create mechanisms that could restrict without delay the distribution of content that could go against the aforementioned restrictions. The fines for individuals who break the law will be of the 10% of the person's last year's income. The law was received with criticism from the opposition on the grounds that it is a violation of freedom of speech protections stipulated in the Venezuelan constitution, and that it encourages censorship and self-censorship.[38]

In November 2013 the Venezuelan telecommunications regulator, the National Commission of Telecommunications (CONATEL), began ordering ISPs to block websites that provide the black market exchange rate. ISPs must comply within 24 hours or face sanctions, which could include the loss of their concessions. Within a month ISPs had restricted access to more than 100 URLs. The order is based on Venezuela's 2004 media law which makes it illegal to disseminate information that could sow panic among the general public.[39]

According to Spanish newspaper El País, CONATEL verifies that ISPs do not allow their subscribers to access content which is "an aggression to the Venezuelan people" and "causes unstabilization", in their criteria. El País also warns that Conatel could force ISPs to block web sites in opposition to the government's interests.[40] It was also reported by El País that there will be possible automations of DirecTV, CANTV, Movistar and possible regulation of YouTube and Twitter.[40]

Following the election establishing the 2017 Constituent National Assembly, the president of the assembly Delcy Rodríguez decreed that there will be "regulation of the emission of messages of hatred and intolerance (and) strong penalties when it is in presence of a crime of hatred and intolerance", singling out opposition politicians while also threatening those who criticized her brother, Jorge Rodriguez.[41] On 8 November 2017, the pro-government Constituent National Assembly approved of increased censorship that would close media organization that promote "hate and intolerance".[42]

Currency exchange websites

It is disallowed for websites to publish the black market currency exchange rate,[39] as the government claims that this contributes to severe economic problems the country is currently reported to be facing.

In 2013, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro banned several internet websites, including DolarToday, to prevent its citizens accessing the country's exchange rates. Maduro, however, accused DolarToday of fueling an economic war against his government and manipulating the exchange rate.[43]

2014 Venezuelan protests

During the 2014 Venezuelan protests, it was reported that Internet access was unavailable in San Cristóbal, Táchira for up to about half a million citizens. Multiple sources claimed that the Venezuelan government blocked Internet access.[44][45][46][47][48] Internet access was reported to be available again one day and a half later.[49]

Social media

Also during the 2014 Venezuelan protests, images on Twitter were reported to be unavailable for at least some users in Venezuela for 3 days (12–15 February), with claims that the Venezuelan government blocked them, indicating that it appeared to be an attempt to limit images of protests against shortages and the world's highest inflation rate.[50][51] Twitter spokesman Nu Wexler stated that, "I can confirm that Twitter images are now blocked in Venezuela" adding that "[w]e believe it's the government that is blocking".[52][53] However, the Venezuelan government published a statement saying that they did not block Twitter or images on Twitter, and implied that it was a technical problem.[30]

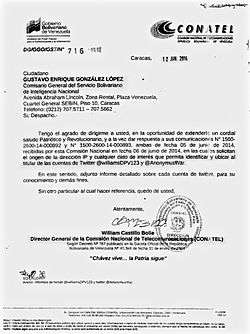

In 2014, multiple Twitter users were arrested and faced prosecution due to the tweets they made.[54] Alfredo Romero, executive director of the Venezuelan Penal Forum (FPV), stated that the arrests of Twitter users in Venezuela was a measure to instill fear among those using social media that were critical against the government.[54] In October 2014, eight Venezuelans were arrested shortly after the death of PSUV official Robert Serra.[55] Though the eight Venezuelans were arrest in October 2014, the Venezuelan government had been monitoring them since June 2014 in leaked documents with the state telecommunications agency, Conatel, providing IP addresses and other details to the Venezuelan intelligence agency SEBIN in order to arrest Twitter users.[55]

Zello

The company Zello announced that CANTV blocked the use of its walkie-talkie app which is used by the opposition.[56] In an interview with La Patilla, Chief Technology Officer of Zello, Alexey Gavrilov, said that after they opened four new servers for Venezuela, it still appeared that the same direct blocking from CANTV is the cause of the Zello outage.[57] The government said Zello was blocked due to "terrorist acts" and made statements on TeleSUR about radical opposition after monitoring staged messages from "Internet trolls" that used a Honeypot trap against authorities.[58]

Public employees

The Ministry of Urban Agriculture forced public employees to email their social media usernames to managers and supervisors in August 2017. This was done in order to "conquer the fourth generation war" against the Bolivarian government, with the government monitoring the Facebook, Instagram and Twitter profiles of their workers.[59]

Legal barriers

Law on Social Responsibility of Radio and Television

The Law on Social Responsibility of Radio and Television (Ley de Responsabilidad de Radio y Televisión in Spanish) entered into force in December 2004. Its stated aim is to "strike a democratic balance between duties, rights, and interests, in order to promote social justice and further the development of the citizenry, democracy, peace, human rights, education, culture, public health, and the nation's social and economic development."

Supporters of the law and detractors have debated its significance in terms of freedom of expression and journalism in the country. Some complained about the fact that it limits violent and sexual content on television and radio during daytime hours in order to protect children. For example, Human Rights Watch argued that these limits are not fair for broadcasters, "making it necessary for them to present a sanitized version of the news during the day".[60] It also suggested that "insult laws" in articles 115, 121 and 125 of the bill could result in political censorship.

Broadcast licences

In May 2007, controversies on press freedom were further exacerbated when RCTV (Radio Caracas Television)'s terrestrial broadcast licence expired, with the government declining to renew it. An article by Reporters Without Borders stated that:

"Reporters Without Borders condemns the decision of the Venezuela Supreme Court to rule an appeal by Radio Caracas Televisión (RCTV) against the loss of its license as "inadmissible". The appeal, lodged on 9 February 2007, was rejected on 18 May, putting a stop to any further debate. President Hugo Chávez said on 28 December 2006 that he would oppose renewal of the group's broadcast license, accusing the channel of having supported the 11 April 2002 coup attempt in which he was briefly removed from office. According to the government the license expired on 27 May 2007, a date contested by RCTV, which insists its license is valid until 2022. Without waiting for the 27 May or the Supreme Court's decision, Hugo Chávez on 11 May awarded RCTV's channel 2 frequency by decree to a new public service channel, Televisora Venezolana Social (TVes)".[61]

This government action fueled student demonstrations and contentious forms of political demonstrations.

After the closure of the TV station on 2007, the station launched a new channel named RCTV International that was broadcast on cable/satellite TV. Following its move to cable, RCTV relaunched itself as RCTV International, in an attempt to escape the regulation of the Venezuelan media law. In mid-2009 the National Commission of Telecommunications (CONATEL) Venezuelan state media regulator, declared that cable broadcasters would be subject to the new media law if 70% or more of their content and operations were domestic.[62] In January 2010 CONATEL concluded that RCTV met that criterion (being more than 90% domestic according to CONATEL), and reclassified it as a domestic media source, and therefore subject to the requirements to broadcast state announcements, known as cadenas. Along with several other cable providers, RCTV refused to do so and was sanctioned with temporary closure. It reopened on cable, which is widely available in Venezuela. Other sanctioned channels include the American Network, America TV and TV Chile. TV Chile, an international channel of Chilean state television, had failed to respond to a January 14 deadline for clarifying the nature of its content.[63] Cable network providers have been encouraged by the Venezuelan government to remove those channels that are found to be in violation of existing media regulations.[64]

Case studies

Ángel Sarmiento

Dr Ángel Sarmiento is President of the State Bar Association of Medical Doctors in Aragua. Besides being a doctor, he is often in the political spotlight because he is a strong advocacy of democracy.[65] In September 2014, the prestigious doctor went on the radio and pronounced eight people dead of the same unknown disease in a hospital in Maracay. All of the deceased patients exhibited the same symptoms which include, fever, respiratory problems, and a rash. Soon after his public statement he was denounced and discredited by public officials.[66] Immediately the governor of Aragua, Tarek El Aissami accused the doctor of launching a terrorist campaign fueled by anxiety. Not much longer after that President Maduro himself publicly condemned the doctor for waging biological and psychological warfare on Venezuela.[67] Both government authorities then asked prosecutors to open an investigation against Sarmiento on grounds of terrorism and for being a "spokesman of the fascist opposition".[66] The Attorney General then appointed a prosecutor for the case with the support of the National Assembly. The official statement from the government on the issue was that this was that they would condemn "media terrorism by right-wing factors of the health sector" and that "psychological terrorism would be severely punished."[68] Two days following his defamation, Dr. Angel Sarmiento fled the country and has not returned since.

Context

"Sarmiento’s statements were made at a time when Venezuela was facing a high number of cases of mosquito-transmitted diseases."[69] Amongst other shortages, medical shortages were debilitating hospitals across the country and the government was unable to provide sufficient medical attention for many patients.[70] There are depleted resources such as medical instruments, drugs, and a lack of basic hospital amenities such as sheets.[71] When Doctor Sarmiento declared the reason of death unknown for the eight deceased in the Maracay Hospital, he simultaneously drew more attention to these problems.[72] Eleven days after the outbreak, doctors were finally able to compile enough resources to discover the cause of death.[73] The death was eventually attributed to chikungunya, a mosquito-borne virus that has treatable symptoms. Some officials who were investigating the deaths reported that the fatal incident was an unidentified hemorrhagic fever. However, after analyzing samples in nongovernmental labs report that there is little doubt that it is chikungunya.[74]

Social media

Social media outlets are important to democracy. They encourage dialogue about candidates and issues, prompting more people to be involved, eventually leading to a better voter turnout.[75] In recent years there has been little to no published information regarding parliamentary affairs. This includes the legislative agenda, appropriations, records of representatives’ votes, and session scripts. Aside from that, the government has classified documents and legislative records that bar anyone inquiring from seeing the actual groundwork of the assembly.[76] The administration under President Maduro has recently said that it is important for the government to keep such things classified to protect children.[77] Private and community media outlets have been barred from hosting press conferences and covering assembly activities. There is no coverage of the representative accomplishments, actions taken, or any form of news to validate their words.[78] Instead of encouraging a diverse landscape of opinion and opposition, anything published that is not aligned with government ideals is denounced and discredited, so politicians rely on social media.[79] Citizens, government officials, and media sources alike are all practicing self-censorship in fear of prosecution and ridiculous accusations. Before a tweet has been sent, the politician sending it has politically charged motivations and has to consider the ramifications if he publishes anything dissenting with the government.[80] Otherwise he could face the same fate as Sarmiento. On December 6, 2015, Venezuelans had elections for the National Assembly. For the first time in many years the opposition took majority. The new opposition majority has promised to restore transparency to the government and to limit President Maduro's ability to exercise his extensive powers.[81]

See also

References

- ↑ "WORLD PRESS FREEDOM INDEX 2015". Report. Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 27 August 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ "Freedom of the Press Worldwide in 2014". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ "Constitution of Venezuela in English" 1999 Constitution of Venezuela

- ↑ "WORLD REPORT | 2014" (PDF). Report. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela: Halt Censorship, Intimidation of Media". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Americas". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Corrales, Javier (April 2015). "The Authoritarian Resurgence". Journal of Democracy. 26 (2): 37–51.

- ↑ "Venezuela - 2014 Scores". Freedom House. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

pressure from the central government on private media ... fosters systematic self-censorship

- ↑ Pomerantsev, Peter (23 June 2015). "Beyond Propaganda". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ "In Venezuela's latest media shift, El Universal newspaper sold". Reuters. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ Otis, John. "Venezuela's El Universal criticized for being tamed by mystery new owners". Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Rueda, Manuel (12 March 2013). "Is Venezuela's Government Silencing Globovision?". ABC News. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Lozano, Daniel (4 June 2013). "Otro avance chavista: se queda con el diario más vendido del país". La Nación. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuelan opposition TV channel Globovision sold". BBC. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Renuncia Jefa de Investigación de Últimas Noticias por censura". Colegios Nacional de Periodistas. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela newspaper prints final edition due to failing economy". Fox News Latino. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "En cinco años, 55 medios impresos dejaron de circular en Venezuela - LaPatilla.com". LaPatilla.com (in Spanish). 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- ↑ Heritage, Andrew (December 2002). Financial Times World Desk Reference. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 618–21. ISBN 9780789488053.

- 1 2 "Para el régimen informar es delito: 49 medios han sido cerrados durante el 2017 por orden de Maduro". La Patilla (in Spanish). 30 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ Arthur Brice (5 June 2009). "Venezuela takes actions against critical TV station". CNN.

- ↑ "Señal del canal NTN24 fue sacada de la parrilla de cable" ("NTN24 channel signal was taken from the wire") (in Spanish), El Universal, 13 February 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ Schipani, Andres (16 February 2014). "Fears grow of Venezuela media crackdown". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro: Denuncio a la Agencia France Press (AFP) porque está a la cabeza de la manipulación – RT". Actualidad.rt.com. 14 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "No Oscars Show for Broadcast TV in Venezuela". ABC News. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ↑ S., Alex Vasquez (2 February 2017). "Outraged with series about Chavez's life, Venezuela prez orders a remake". Fox News. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ "Caracol TV y RCN ya no se ven en Venezuela por orden del gobierno". El Nacional. 24 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Venezuela". Freedom House. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ http://12mars.rsf.org/2014-en/#slide3

- ↑ "Reporters without Borders warn about Internet censorship in Venezuela". El Universal. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- 1 2 OpenNet Initiative "Summarized global Internet filtering data spreadsheet", 29 October 2012 and "Country Profiles", the OpenNet Initiative is a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- ↑ Due to legal concerns ZOpenNet Initiative does not check for filtering of child pornography and because their classifications focus on technical filtering, they do not include other types of censorship.

- ↑ "Venezuela". OpenNet Initiative. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Lopez, Linette (26 May 2015). "Venezuela says it's working on a way to kill Google and Mozilla so no one knows about its currency crash". Business Insider. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela Country Report | Freedom on the Net 2017". Freedom House. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ↑ "Denuncian que Cantv bloqueó acceso a web de El Pitazo". La Patilla (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ↑ "El Nacional Web responde sobre proceso sancionatorio de Conatel". La Patilla (in Spanish). 22 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ "Aprueban ley que regula contenidos de Internet y medios en Venezuela (new law regulates contents on the Internet in Venezuela), El Tiempo.com, 20 December 2010

- 1 2 "Venezuela forces ISPs to police Internet", John Otis, Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), 12 December 2013.

- 1 2 Meza, Alfredo (13 March 2014). "El régimen venezolano estrecha el cerco sobre internet". El Pais. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ "ANC cubana regulará uso de redes sociales para sancionar "delitos de odio"". La Patilla. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ "Venezuela Passes 'Anti-Hate Law' to Clamp Down on the Media". Bloomberg. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ December 5, 2013. "Venezuela cracks down on the Internet's hugely popular Bitly site". Associated Press. Daily News. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Táchira militarizada y sin Internet luego de 16 días de protestas" Archived 2014-03-10 at the Wayback Machine. ("Táchira without Internet militarized after 16 days of protests") (in Spanish), Eleonora Delgado, Adriana Chirinos, and Cesar Lira, El Nacional, 21 February 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Táchira amanece sin Internet por segundo día" Archived 2014-03-10 at the Wayback Machine. ("Táchira dawns without Internet for second day") (in Spanish), Eleonora Delgado, El Nacional, 21 February 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela: Táchira se quedó militarizada y sin internet" ("Venezuela: Táchira remained militarized without internet") (in Spanish), Terra, 20 February 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Denuncian que en el Táchira no hay agua, internet, ni servicio telefónico" ("They claim that in Tachira no water, internet, or phone service") (in Spanish), Informe21, 20 February 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ O'Brien, Danny. "Venezuela's Internet Crackdown Escalates into Regional Blackout". EFF. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ http://el-informe.com/21/02/2014/general/vuelve-internet-a-san-cristobal-donde-manifestaciones-y-disturbios-no-cesan/

- ↑ "Twitter reports image blocking in Venezuela", USA Today (AP), 14 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuelans Blocked on Twitter as Opposition Protests Mount", Patricia Laya, Sarah Frier and Anatoly Kurmanaev, Bloomberg News, 14 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Twitter confirma bloqueo de imágenes en Venezuela". BBC. 15 February 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ "Empresa de telecomunicaciones de Venezuela niega bloqueo de Twitter". El Tiempo. 14 February 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Venezuela: ya son siete los tuiteros detenidos por "opiniones inadecuadas"". Infobae. 1 November 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Netizen Report: Leaked Documents Reveal Egregious Abuse of Power by Venezuela in Twitter Arrests". Global Voices Online. 17 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Bajack, Frank (21 February 2014). "Venezuela Cuts Off Internet, Blocks Communication For Protestors". Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Zello se actualizó para ayudar a los venezolanos (Entrevista Exclusiva)". La Patilla. 22 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ "Zello: la "aplicación terrorista" de los estudiantes venezolanos". Infobae. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Espionaje socialista: Gobierno vigilará a trabajadores públicos a través de redes sociales". La Patilla (in Spanish). 11 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch, "2003 World Report"

- ↑ Reporters Without Borders (2007) press releases: Americas, "Supreme Court rules RCTV's appeal against loss of its license 'inadmissible'" Archived September 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Venezuelanalysis, 22 January 2010, Venezuela Applies Media Social Responsibility Law to Cable Channels

- ↑ Santiago Times, 26 January 2010, TV Chile faces "temporary" ban for refusing to broadcast Chavez speech

- ↑ Venezuelanalysis, 25 January 2010, Venezuela Sanctions Cable Television Channels for Failure to Comply with Media Law

- ↑ "Entrevista Ángel Sarmiento Presidente del Colegio Médico del estado Aragua - Vuclip". vu6.vuclip.com. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- 1 2 "Report: Even low-profile critics in Venezuela being muzzled by courts". miamiherald. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Maduro denuncia guerra biológica contra Venezuela | Globovisión". archivo.globovision.com. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Venezuela: Critics Under Threat". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Venezuela: Critics Under Threat". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ Neuman, William (2015-12-08). "Opposition in Venezuela Now Has to Fix the Ills That Led to Its Victory". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Venezuela Healthcare Crisis: Under Maduro, Medical Shortages Reaching Critical Level". International Business Times. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Maduro's muzzle". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Virus mortal se extiende en Venezuela, gobierno lo niega". CubaNet Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "In Venezuela, doctor flees after being accused of terrorism amid fever outbreak". news.sciencemag.org. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Facts about Venezuela's Presidential Elections and the Voting Process | venezuelanalysis.com". venezuelanalysis.com. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ Anita, Breuer; Yanina, Welp, eds. (2014-01-01). Digital technologies for democratic governance in Latin America: opportunities and risks. Routledge.

- ↑ "World Report 2014: Venezuela". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ Acosta-Alzuru, Carolina. "Propaganda and self-censorship in Venezuelan media". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Refworld | Venezuela: Critics Under Threat". Refworld. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Inciting self-censorship". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ 12, November; English, 2015Click to read this article in Spanish Click to read this article in. "157 legislators call for "free, transparent and democratic" elections in Venezuela". Retrieved 2015-12-12.

External links

- CONATEL, official web site in Spanish. (English translation)