Feline infectious peritonitis

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is the name given to an uncommon, but usually fatal, aberrant immune response to infection with feline coronavirus (FCoV).[1]

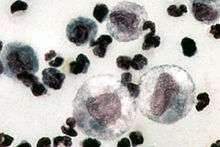

The virus and pathogenesis of FIP

FCoV is a virus of the gastrointestinal tract: most infections are either asymptomatic, or cause diarrhea, especially in kittens, as maternally derived antibody wanes at between 5 and 7 weeks of age. The virus is a mutation of feline enteric coronavirus (FECV). From the gut, the virus very briefly undergoes a systemic phase,[2] returning to the gut, from where it is shed in the feces. The pathogenesis of FIP is complicated: the reductionist view is that it is entirely due to mutation of the virus, enabling it to enter, or replicate more successfully in, monocytes.[3] The holistic approach is that FIP occurs as a result of a number of factors, including viral virulence (some strains are undoubtedly more virulent than others), and the immune status and general health of the host.

Virus transmission

FCoV is common in places where large groups of cats are housed together indoors (e.g. breeding catteries, animal shelters, etc.). The virus is shed in feces and cats become infected by ingesting or inhaling the virus, usually by sharing cat litter trays, or by the use of contaminated litter scoops or brushes transmitting infected microscopic cat litter particles to uninfected kittens and cats.[4] Direct, cat-to-cat, virus transmission does not commonly occur.

Clinical signs

There are two main forms of FIP: effusive (wet) and non-effusive (dry). While both types are fatal, the effusive form is more common (60–70% of all cases are wet) and progresses more rapidly than the non-effusive form.

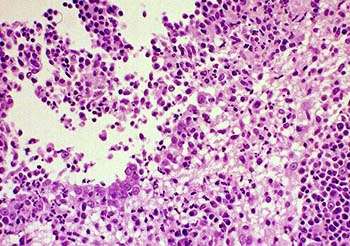

Effusive (wet) FIP

The hallmark clinical sign of effusive FIP is the accumulation of fluid within the abdomen or chest, which can cause breathing difficulties. Other symptoms include lack of appetite, fever, weight loss, jaundice, and diarrhea.

Non-effusive (dry) FIP

Dry FIP will also present with lack of appetite, fever, jaundice, diarrhea, and weight loss, but there will not be an accumulation of fluid. Typically a cat with dry FIP will show ocular or neurological signs. For example, the cat may develop difficulty in standing up or walking, becoming functionally paralyzed over time. Loss of vision is another possible outcome of the disease.

Diagnosis

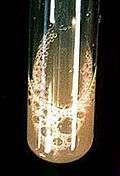

Diagnosing effusive FIP

Diagnosis of effusive FIP has become more straightforward in recent years: detection of viral RNA in a sample of the effusion, by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is diagnostic of effusive FIP.[5][6][7] However, that does require that a sample be sent to an external veterinary laboratory. Within the veterinary hospital there are a number of tests which can rule out a diagnosis of effusive FIP within minutes:

- Measure the total protein in the effusion: if it is less than 35g/l, FIP is extremely unlikely.

- Measure the albumin to globulin ratio in the effusion: if it is over 0.8, FIP is ruled out, if it is less than 0.4, FIP is a possible—but not certain—diagnosis[8]

- Examine the cells in the effusion: if they are predominantly lymphocytes then FIP is excluded as a diagnosis.

Diagnosing non-effusive FIP

Non-effusive FIP is more difficult to diagnose than effusive FIP because the clinical signs tend to be more vague and varied: the list of differential diagnoses is therefore much longer. Non-effusive FIP diagnosis should be considered when the following criteria are met:[9]

- History: the cat is young (under 2 years old) and purebred: over 70% of cases of FIP are in pedigree kittens.

- History: the cat experienced stress such as recent neutering or vaccination[10]

- History: the cat had an opportunity to become infected with FCoV, such as originating in a breeding or rescue cattery, or the recent introduction of a purebred kitten or cat into the household.

- Clinical signs: the cat has become anorexic or is eating less than usual; has lost weight or failed to gain weight; has pyrexia of unknown origin; intra-ocular signs; icterus.[11]

- Biochemistry: hypergammaglobulinaemia; raised bilirubin without liver enzymes being raised.

- Hematology: lymphopenia; non-regenerative—usually mild—anaemia.

- Serology: the cat has a high antibody titre to FCoV: this parameter should be used with caution, because of the high prevalence of FCoV in breeding and rescue catteries.

Non-effusive FIP can be ruled out as a diagnosis if the cat is seronegative, provided the antibody test has excellent sensitivity. In a study which compared various commercially available in-house FCoV antibody tests,[12] the FCoV Immunocomb (Biogal) was 100% sensitive; the Speed F-Corona rapid immunochromatographic (RIM) test (Virbac) was 92.4% sensitive and the FASTest feline infectious peritonitis (MegaCor Diagnostik) RIM test was 84.6% sensitive.

Treatment

Because FIP is an immune-mediated disease, treatment falls into two categories: direct action against the virus itself and modulation of the immune response.

Antiviral drugs

The most commonly available antiviral drugs for treating FIP are either feline recombinant interferon omega (Virbagen Omega, Virbac) or human interferon. Since the action of interferon is species-specific, feline interferon is more efficacious than human interferon.

An experimental antiviral drug called GC 376 was used in a field trial of 20 cats: 7 cats went into remission, 13 cats responded initially but relapsed and were euthanized. [13] This drug is not yet commercially available.

Modulation of the immune response

The go-to immunosuppressive drug in FIP is prednisolone.

An experimental polyprenyl immunostimulant (PI) is manufactured by Sass and Sass and tested by Dr. Al Legendre, who described survival over 1 year in three cats diagnosed with FIP and treated with the medicine.[14] In a subsequent field study of 60 cats with non-effusive FIP treated with PI, 52 cats (87%) died before 200 days, but eight cats survived over 200 days from the start of PI treatment for and four of those survived beyond 300 days.[15] There are anecdotal reports on the internet of cats surviving even longer.[16]

Prevention of FIP

Vaccination

There is one intra-nasal FIP vaccine available: its use is controversial but in an independent study the authors concluded that vaccination can protect cats with no or low FCoV antibody titres and that in some cats vaccine failure was probably due to pre-existing infection.[17]

Prevention of FCoV infection, and therefore FIP, in kittens

Kittens are protected from infection by maternally derived antibody until it wanes, usually around 5–7 weeks of age, therefore it is possible to prevent infection of kittens by removing them from sources of infection.[18] However, FCoV is a very contagious virus and such prevention does require rigorous hygiene.

See also

References

- ↑ Addie D, Belák S, Boucraut-Baralon C, et al. Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 594–604

- ↑ Porter E, Tasker S, Day MJ, Harley R, Kipar A, Siddell SG, Helps CR. 2014 Amino acid changes in the spike protein of feline coronavirus correlate with systemic spread of virus from the intestine and not with feline infectious peritonitis. Vet Res. 45:49.

- ↑ Pedersen NC. An update on feline infectious peritonitis: virology and immunopathogenesis. Vet J. 2014 Aug;201(2):123-32.

- ↑ How cats become infected with feline coronavirus: animation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkqUjeQNEQs

- ↑ Felten S, Leutenegger CM, Balzer H-J, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction detecting feline coronavirus mutations in effusion and serum/plasma of cats to diagnose feline infectious peritonitis. BMC Vet Res 2017; 13: 228.

- ↑ Doenges SJ, Weber K, Dorsch R, et al. Comparison of real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, serum and cell-free body cavity effusion for the diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 344–350.

- ↑ Longstaff L, Porter E, Crossley VJ, et al. Feline coronavirus quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on effusion samples in cats with and without feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 240–245.

- ↑ Addie:Diagnosis of FIP. http://www.catvirus.com/WhatIsFIP.htm#Diagnosis%20of%20FIP

- ↑ Diagnosis of FIP. http://www.catvirus.com/WhatIsFIP.htm#Diagnosis%20of%20FIP

- ↑ Riemer F, Kuehner KA, Ritz S, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of cats with feline infectious peritonitis – a retrospective study of 231 confirmed cases (2000–2010). J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 348–356.

- ↑ Addie: FIP and Coronavirus. 2013. ISBN 978-1480208971

- ↑ Addie DD, le Poder S, Burr P, et al. Utility of feline coronavirus antibody tests. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 152–162.

- ↑ Pedersen NC, Kim Y, Liu H, Galasiti Kankanamalage AC, Eckstrand C, Groutas WC, Bannasch M, Meadows JM, Chang KO. 2017 Efficacy of a 3C-like protease inhibitor in treating various forms of acquired feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg.

- ↑ Legendre AM, Bartges JW. 2009 Effect of Polyprenyl Immunostimulant on the survival times of three cats with the dry form of feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg. 11 624-626

- ↑ Legendre AM, Kuritz T, Galyon G, Baylor VM, Heidel RE. Polyprenyl Immunostimulant Treatment of Cats with Presumptive Non-Effusive Feline Infectious Peritonitis In a Field Study. Front Vet Sci. 2017 Feb 14;4:7.

- ↑ "Hope for Nearly Fatal Cat Disease". Cat Channell. Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ↑ Fehr D, Holznagel E, Bolla S, Hauser B., Herrewegh AAPM, Horzinek MC, Lutz H. 1997. Placebo-controlled evaluation of a modified life virus vaccine against feline infectious peritonitis: safety and efficacy under field conditions. Vaccine 15 10 1101-1109

- ↑ Addie D.D., Jarrett O. 1992 A study of naturally occurring feline coronavirus infection in kittens. Vet. Rec. 130 133-137

External links

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis and Coronavirus Website

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis from vetinfo.com

- Research on Feline Infectious Peritonitis from University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine

- FIP: A 2012 Update

- FIP Informational Brochure from the Cornell Feline Health Center

- UC Davis Center for Companion Animal Health

- Animal Health Channel

- Feline Advisory Bureau

- FIP (Felipedia.org)