C/1861 J1

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | John Tebbutt |

| Discovery date | May 13, 1861[1] |

| Orbital characteristics A | |

| Epoch |

JD 2400920.5 (921.0?) (May 25, 1861) |

| Aphelion | 109 AU |

| Perihelion | 0.822 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 55.1 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.985 |

| Orbital period | 409 a |

| Inclination | 85.4° |

| Last perihelion | June 12, 1861 |

| Next perihelion | 2265[2] |

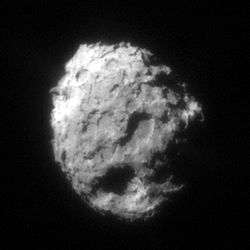

The Great Comet of 1861 formally designated C/1861 J1 and 1861 II, is a long-period comet that was visible to the naked eye for approximately 3 months.[3] It was categorized as a Great Comet, one of the eight greatest comets of the 19th century, according to Donald Yeomans.[3]

It was discovered by John Tebbutt of Windsor, New South Wales, Australia, on May 13, 1861, with an apparent magnitude of +4, a month before perihelion (June 12). It was not visible in the northern hemisphere until June 29, but it arrived before word of the comet's discovery.

On June 29, 1861, comet C/1861 J1 passed 11.5 degrees from the Sun.[4] On the following day, June 30, 1861, the comet made its closest approach to the Earth at a distance of 0.1326 AU (19,840,000 km; 12,330,000 mi).[1] During the Earth close approach the comet was estimated to be between magnitude 0[3] and −2[1] with a tail of over 90 degrees.[3] As a result of forward scattering C/1861 J1 even cast shadows at night (Schmidt 1863; Marcus 1997).[5] During the night of 1861 June 30 – July 1, the famed comet observer J. F. Julius Schmidt watched in awe as the great comet C/1861 J1 cast shadows on the walls of the Athens Observatory.[5] The comet may have interacted with the Earth in an almost unprecedented way. For two days, when the comet was at its closest, the Earth was actually within the comet's tail, and streams of cometary material converging towards the distant nucleus could be seen.

By the middle of August the comet was no longer visible to the naked eye, but it was visible in telescopes until May 1862. An elliptical orbit with a period of about 400 years was calculated, which would indicate a previous appearance about the middle of the 15th century, and a return in the 23rd century.

I. Hasegawa and S. Nakano suggest that this comet is identical with C/1500 H1 that came to perihelion on 1500 April 20 (based on 5 observations).[6]

By 1992 this Great Comet had traveled more than 100 AU from the Sun, making it even farther away than dwarf planet Eris. It will come to aphelion around 2063.

It was hypothesized that C/1861 G1 (Thatcher) and this comet are related, and that in a previous perihelion (possibly the 1500 one) and that C/1861 G1 broke off of this comet, as the two comets have many similar orbital characteristics. However, this was disproved in 2015 by Richard L. Branham Jr., who used modern computing technology and statistical analysis to calculate a corrected orbit for C/1861 J1.[7]

Tebbutt's account

In his Astronomical Memoirs Tebbutt gave an account of his discovery:[8]

... On the evening of May 13, 1861, while searching the western sky for comets, I detected a faint nebulous object near the star Lacaille 1316 in the constellation Eridanus. In my marine telescope the object appeared much diffused, and it was with the greatest difficulty that I estimated its distance from three well known fixed stars. The object was hardly distinguishable in the small telescope attached to the sextant, and I found it necessary to employ a coloured glass between the index and horizon glasses, for the superior brilliance of the reference stars Procyon, Sirius and Canopus, when they were brought into the field of view, quite extinguished its feeble light. The measurements gave R.A. = 3 h. 54 m. 12 s. Declin. = —30° 44′ as the place of the object at 6 h. 57 m. local mean time. Every comet hunter knows how necessary it is to the carrying out of his work to have at hand a copious catalogue of nebulae, but this valuable adjunct I unfortunately did not possess. I could not, however, find the object in the limited catalogues at my command. I accordingly made up my mind to watch it, and it is well that I did so, otherwise I should have missed one of the best opportunities for introducing myself to the astronomical world. ...

Observations in writing

Granville Stuart noted the observation of this comet in a journal entry on July 1, 1861 while living in western Montana. The entry reads as follows: "Saw a huge comet last night in the northwest. Its tail reached half across the heavens. It has probably been visible for sometime, but as it has been cloudy lately I had not observed it before."[9]

June 1861

June 30

| “ | The evening of the escape of the Sumter was one of those Gulf evenings, which can only be felt, and not described. The wind died gently away, as the sun declined, leaving a calm, and sleeping sea, to reflect a myriad of stars. The sun had gone down behind a screen of purple, and gold, and to add to the beauty of the scene, as night set in, a blazing comet, whose tail spanned nearly a quarter of the heavens, mirrored itself within a hundred feet of our little bark, as she ploughed her noiseless way through the waters.[10] | ” |

“At 9.p.m. a large luminous disc surrounded by a nebulous haze became visible in the N.W. horizon. At 9.40 it unmistakably assumed the character, to the naked eye, of a comet, having a large nucleus & a fan-like tail projecting vertically towards the zenith. It was permanently brilliant until sunrise the next morning[?] − travelling with apparent rapidity, but slight declination, from N.W. to N.E.”[11]

July 1861

July 1

| “ | Light rains this morning, I went with Mrs. Brewer, to visit Mrs. Hampton. O. busy, preparing C. to attend a camp-drill of some weeks above here. A brilliant and beautiful comet appeared tonight in the same part of the heavens as that a few years ago, the train of this it the longest that I ever saw, pointing directly upwards.[12] | ” |

| “ | Day passed into night, and with the night came the brilliant comet again, lighting us on our way over the waste of waters. The morning of the second of July, our second day out, dawned clear, and beautiful, the Sumter still steaming in an almost calm sea, with nothing to impede her progress.[13] | ” |

| “ | Its appearance was sublime, as it extended over nearly half of the heavens...many wondered if the world was not coming to an end.[14][15] | ” |

"A very brilliant comet had been visible in the Northern sky during the preceding week. I measured its tail with a quadrant, the extreme length of which was 93 degrees 50 minutes."[16]

July 5, 1861 . "I awoke in the night at 1 o’clock, when I had a glorious sight of the largest comet I ever beheld. The head, or nucleus, was large as Venus, and very bright and blazing, and about 20 degrees above the horizon, pointed to the north, while the bright, long tail reached full half way across the heavens. It was a most wonderful sight." James Riley Robinson, on the schooner Conchita, in the Mexican harbor of Agiabampo.[17]

References

- 1 2 3 Kronk, Gary W (2001–2005). "C/1861 J1 (Great Comet of 1861)". Cometography.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ↑ C/1861 J1 ( Great comet ) Seiichi Yoshida

- 1 2 3 4 Donald K. Yeomans (April 2007). "Great Comets in History". Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology (Solar System Dynamics). Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ↑ Horizons output. "Observer Table for Comet C/1861 J1 (Great comet)". Retrieved 2011-08-22. (Observer Location:500)

- 1 2 Marcus, Joseph C. (2007). "Forward-Scattering Enhancement of Comet Brightness. I. Background and Model". International Comet Quarterly. 29 (2): 39–66. Bibcode:2007ICQ....29...39M.

- ↑ Hasegawa, Ichiro; Nakano, Syuichi (October 1995). "Periodic Comets Found in Historical Records". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 47 (5): 699–710. Bibcode:1995PASJ...47..699H.

- ↑ Branham Jr., Richard L. (2015). "Do comets C/1861 G1 (Thatcher) and C/1861 J1 (Great comet) have a common origin?" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 51: 247–253. Bibcode:2015RMxAA..51..247B. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Tebbutt, John (1908). "evening of May 13, 1861". Astronomical Memoirs. Sydney. pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Stuart, Granville. Forty Years on the Frontier p. 178.

- ↑ Semmes, Raphael. Memoirs of Service Afloat, During the War Between the States Pg. 121.

- ↑ Samuel Elliott Hoskins, Meteorological Register, Guernsey. (He also recorded that the comet was visible on July 2.)

- ↑ Sarah R. Espy (1859–1868). "Private journal". Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ↑ Semmes, Raphael. Memoirs of Service Afloat, During the War Between the States Pg. 125.

- ↑ Emily Holder, wife of Joseph Bassett Holder, while stationed at Fort Jefferson, Florida

- ↑ Reid, Thomas. America's Fortress. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 48. ISBN 9780813030197.

- ↑ Martin Bienvenu, officer on ship at Bangkok, unpublished journal.

- ↑ Diary of John R. Robinson, Feb 14 to Sept 15, 1861: His journey to Batopilas, Mexico in Inspect Silver Mines, with a View to Purchase. http://www.torski.com/family/jrrobinson/pgjrr1stdiarymain.htm. Also located in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

External links

- C/1861 J1 (Great Comet of 1861) on Cometography.com

- The Comet of 1861, Gallery of Natural Phenomena

- JPL DASTCOM Comet Orbital Elements

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris