Great Comet of 1577

.png)

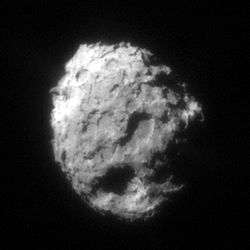

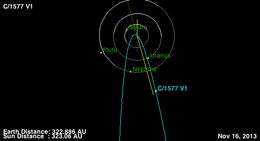

The Great Comet of 1577 (official designation: C/1577 V1) is a non-periodic comet that passed close to Earth during the year 1577 AD. Having an official designation beginning with "C" classes it as a non-periodic comet, and so it is not expected to return. In 1577, the comet was viewed by people all over Europe, including the famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and Turkish astronomer Taqi ad-Din. From his observations of the comet, Brahe was able to discover that comets and similar objects travel above the Earth's atmosphere.[1] The best fit using JPL Horizons suggests that the comet is currently about 320 AU from the Sun (based on 24 of Brahe's observations spanning 74 days from 13 November 1577 to 26 January 1578).[2][3]

Observations by Brahe and others

Using all the records to estimate the orbit, it seems that the perihelion was on October 27. The first recorded observation is from Peru[4], 5 days later: the accounts noted that it was seen through the clouds like the moon. On November 7, in Ferrara (Italy), architect Pirro Ligorio described "the comet shimmering from a burning fire inside the dazzling cloud."[5] On November 8, it was reported by Japanese astronomers with a Moon-like brightness and a white tail spanning over 60 degrees[6] [4]

Tycho Brahe, who is said to have first viewed the comet slightly before sunset on November 13[7] after having returned from a day of fishing,[8] was the most distinguished observer and documenter of the comet's passing.

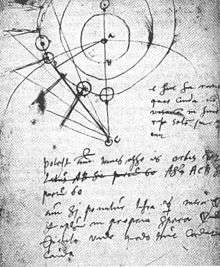

Sketches found in one of Brahe's notebooks seem to indicate that the comet may have travelled close to Venus. These sketches depict the Earth at the centre of the Solar System, with the Sun and moon in orbit and the other planets revolving around the Sun, a model that was later displaced by heliocentricity.[1] Brahe made thousands of very precise measurements of the comet's path, and these findings contributed to Johannes Kepler's theorising of the laws of planetary motion and realisation that the planets moved in elliptical orbits.[9] Kepler, who was Brahe's assistant during his time in Prague, believed that the comet's behavior and existence was proof enough to displace the theory of celestial spheres, although this view turned out to be overly optimistic about the pace of change.[10]

Brahe's discovery that the comet's coma faced away from the Sun was also significant.

One failing Brahe had in his measurements was in exactly how far out of the atmosphere the comet was, and he was unable to supply meaningful and correct figures for this distance;[11] however, he was, at least, successful in proving that the comet was beyond the orbit of the Moon about the Earth,[8] and, further to this, was probably near three times further away.[12] He did this by comparing the position of the comet in the night sky where he observed it (the island Hven, near Copenhagen) with the position observed by Thadaeus Hagecius (Tadeáš Hájek) in Prague at the same time, giving deliberate consideration to the movement of the Moon. It was discovered that, while the comet was in approximately the same place for both of them, the Moon was not, and this meant that the comet was much further out.[13]

Brahe's finding that comets were heavenly objects, while widely accepted, was the cause of a great deal of debate up until and during the seventeenth century, with many theories circulating within the astronomical community. Galileo claimed that comets were optical phenomena, and that this made their parallaxes impossible to measure. However, his hypothesis was not accepted.[11]

Several other observers[14] have recorded seeing the comet: The astronomer Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf[15] recorded the passage of the comet. The Sultan Murad III saw these observations as a bad omen for the war and blamed al-Din for the plague which spread at the time.[16] Other observers include Helisaeus Roeslin, William IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel,[17] Cornelius Gemma, who noted the comet had two tails[4][18] and Michael Mästlin[19] — also identified it as superlunary. Additionally it was also observed by Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, who recorded the comet's passage in the Akbarnama [4]

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe Observations by Brahe of the Great Comet of 1577

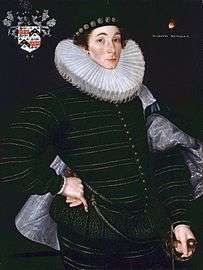

Observations by Brahe of the Great Comet of 1577 Richard Goodricke, by Cornelis Ketel c.1578, with comet top right.

Richard Goodricke, by Cornelis Ketel c.1578, with comet top right.

In art and literature

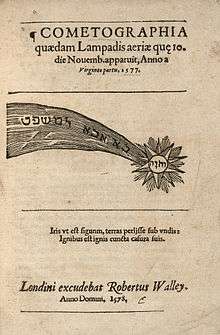

The literature resulting from the passing of the comet was prolific, and these works, as well as the ideas presented by many astronomers, caused much controversy. However, the idea that comets were heavenly objects became a respected theory, and many took this concept to be true.[11] Artwork inspired by the event was also made—artist Jiri Daschitzky made an engraving that was inspired by the passing of the comet over Prague on November 12, 1577. Cornelis Ketel painted the portrait of Richard Goodricke around 1578. Goodricke had reached adulthood in 1577 and apparently saw the comet as an omen and had it included in the painting. Roeslin also produced one of the more complex of the representations of the Great Comet, described as "an interesting, though crude, attempt".[20]

Contemporary references

This comet was mentioned in the book entitled "Sêfer Chazionot - The Book Of Visions - By Rabbi Hayyim ben Joseph Vital: "1577. Rosh Hodesh Kislev (November 11), after sunrise, a large star with a long tail, pointing upward, was seen in the southwestern part of the sky. Part of the tail was also pointing eastward. It lingered there for three hours. Then it sank in the west behind the hills of Safed. This continued for more than fifty nights. On the fifteenth of Kislev, I went to live in Jerusalem".

In Ireland, the Great Comet was observed, and an account of its passing was later inserted in the Annals of the Four Masters:

- A wonderful star appeared in the south-east in the first month of winter: it had a curved bow-like tail, resembling bright lightning, the brilliancy of which illuminated the earth around, and the firmament above. This star was seen in every part of the west of Europe, and it was wondered at by all universally. (Annals of the Four Masters (M1577.20))

Notes

- 1 2 "The comet of 1577". Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- 1 2 NASA. JPL Small-body database browser plot and approximate distance. (needs Java)

- ↑ NASA. JPL HORIZONS current ephemeris more accurate position, no plot.

- 1 2 3 4 Kapoor, R. C. "Abū'l Faẓl, independent discoverer of the Great Comet of 1577". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage (ISSN 1440-2807), Vol. 18, No. 3, p. 249-260.

- ↑ Ginette Vagenheim (2014). "Une description inédite de la grande comète de 1577 par Pirro Ligorio avec une note sur la rédaction des Antichità Romane à la cour du duc Alphonse II de Ferrare" (PDF). La festa delle arti (in French). Rome: 304-305.

- ↑ Rao, Joe (December 23, 2013). "'Comets of the Centuries': 500 Years of the Greatest Comets Ever Seen". space.com.

- ↑ Seargent, p.105

- 1 2 Grant, p.305

- ↑ Gilster, p.100

- ↑ Seargent, p. 107

- 1 2 3 "The Galileo Project". Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ↑ Seargent, p.107

- ↑ Lang, p.240

- ↑ Moritz Valentin Steinmetz: Von dem Cometen welcher im November des 1577. Jars erstlich erschienen, und noch am Himmel zusehen ist, wie er von Abend und Mittag, gegen Morgen und Mitternacht zu, seinen Fortgang gehabt, Observirt und beschrieben in Leipzig ..., Gedruckt bey Nickel Nerlich Formschneider, 1577

- ↑ Ünver, Ahmet Süheyl (1985). İstanbul Rasathanesi. Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu Türk Tarih Kurumu yayınları. pp. 3–6.

- ↑ "The Story of the Two Astronomers Who Studied the Great Comet of 1577". Interesting Engineering. September 5, 2016.

- ↑ Tofigh Heidarzadeh. A History of Physical Theories of Comets, From Aristotle to Whipple. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 47.

- ↑ Gemma, Cornelius (1577). De naturae divinis characterismis. Antwerpen: Plantin, Christophe.

- ↑ J J O'Connor and E F Robertson. "biography of Michael Mästlin".

- ↑ Robert S. Westman, "The Comet and the Cosmos: Kepler, Mästlin, and the Copernican Hypothesis", in The Reception of Copernicus' Heliocentric Theory: Proceedings of a Symposium Organized by the Nicolas Copernicus Committee of the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science, Torun, Poland, 1973 (Springer, 1973), pp. 10 and 28. For a description and reproduction of Helisaeus Roeslin's diagram, see pp. 28–29 online.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Comet of 1577. |

- Seargent, David (2009). The Greatest Comets in History. Springer. ISBN 0-387-09512-8.

- R. Lang, Kenneth; Charles Allen Whitney (1991). Wanderers in Space. CUP Archive. p. 240. ISBN 0-521-42252-3.

- Gilster, Paul (2004). Centauri Dreams. Springer. p. 100. ISBN 0-387-00436-X.

- Grant, Robert. History of Physical Astronomy, from the Earliest Ages to the Middle of the 19th Century. R. Baldwin, 1852. p. 305.