Fatal Attraction

| Fatal Attraction | |

|---|---|

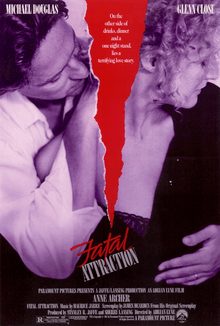

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Adrian Lyne |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | James Dearden |

| Based on |

Diversion by James Dearden |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

| Cinematography | Howard Atherton |

| Edited by | |

Production company |

Jaffe/Lansing Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $14 million |

| Box office | $320.1 million[1] |

Fatal Attraction is a 1987 American psychological erotic thriller film directed by Adrian Lyne and written by James Dearden. It is based on Dearden's 1980 short film Diversion. Featuring a cast of Michael Douglas, Glenn Close, Anne Archer and Ellen Hamilton Latzen, the film centers on a married man who has a weekend affair with a woman who refuses to allow it to end and becomes obsessed with him.

The film was a massive box office hit, finishing as the second-highest-grossing film of 1987 in the United States and the highest-grossing film of the year worldwide. Critics were enthusiastic about the film, and it received six Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture (which it lost to The Last Emperor), Best Actress for Close, and Best Supporting Actress for Archer. Both lost to Cher and Olympia Dukakis, respectively, for Moonstruck.

Plot

Dan Gallagher is a successful, happily married Manhattan lawyer whose work leads him to meet Alexandra "Alex" Forrest, an editor for a publishing company. While his wife, Beth, and daughter, Ellen, are out of town for the weekend, Dan has an affair with Alex. Though it was initially understood by both as just a fling, Alex starts clinging to him.

Dan spends a second unplanned evening with Alex after she persistently asks him over. When Dan tries to leave, she cuts her wrists in a suicide attempt. He helps her bandage the cuts and then leaves. He thinks the affair is forgotten, but she shows up at various places to see him. She waits at his office one day to apologize and invites him to a performance of Madame Butterfly, but he politely turns her down. She then continues to call him until he tells his secretary that he will no longer take her calls. Alex then phones his home at all hours, claiming that she is pregnant and plans to keep the baby. Although he wants nothing to do with her, she argues that he must take responsibility. After he changes his home phone number, she shows up at his apartment (which is for sale) and meets Beth, feigning interest as a buyer. Later that night, Dan goes to Alex's apartment to confront her, which results in a scuffle. In response, she replies that she will not be ignored.

Dan moves his family to Bedford, but this does not deter Alex. She has a tape recording delivered to him filled with verbal abuse. She stalks him in a parking garage, pours acid on his car, and follows him home one night to spy on him, Beth, and Ellen from the bushes in their yard; the sight of their content family literally makes her sick to her stomach. Her obsession escalates further when Dan approaches the police to apply for a restraining order against Alex (claiming that it is "for a client"). The lieutenant claims that he cannot violate her rights without probable cause, and that the "client" has to own up to his adultery.

At one point, while the Gallaghers are not home, Alex kills Ellen's pet rabbit, and puts it on their stove to boil. After this, Dan tells Beth of the affair and Alex's supposed pregnancy. Enraged, she demands that Dan leave. Before he goes, Dan calls Alex to tell her that Beth knows about the affair. Beth gets on the phone and warns Alex that she will kill her if she persists. Without Dan and Beth's knowledge, Alex picks up Ellen from school and takes her to an amusement park. Beth panics when she realizes that she does not know where Ellen is. She drives around frantically searching and rear-ends a car stopped at an intersection. Beth gets injured and is then hospitalized. Alex later takes Ellen home, asking her for a kiss on the cheek. Following Beth's release from the hospital, she forgives Dan and they return home.

Dan barges into Alex's apartment and attacks her, choking her and coming close to strangling her. He stops himself, but as he does, she lunges at him with a kitchen knife. He overpowers her but decides to put the knife down and leave, while Alex is leaning against the kitchen counter, smiling. The police begin to search for her after Dan confronts them about having her arrested.

Beth prepares a bath for herself when Alex suddenly appears, again with the kitchen knife. She starts to explain her resentment of Beth, nervously fidgeting (which causes Alex to cut her own leg) and then attacks Beth. Dan hears the screaming, rushes in, wrestles Alex into the bathtub, and seemingly drowns her. She suddenly emerges from the water, swinging the knife. Beth, who went searching for Dan's gun, shoots Alex in the chest, killing her. The final scene shows police cars outside the Gallaghers' house. As Dan finishes delivering his statement to the police, he walks inside, where Beth is waiting for him. They embrace and proceed to the living room as the camera focuses on a picture of them and Ellen.

Cast

- Michael Douglas as Dan Gallagher

- Glenn Close as Alexandra "Alex" Forrest

- Anne Archer as Beth Rogerson Gallagher

- Ellen Hamilton Latzen as Ellen Gallagher

- Stuart Pankin as Jimmy

- Ellen Foley as Hildy

- Fred Gwynne as Arthur

- Meg Mundy as Joan Rogerson, Beth's mother

- Tom Brennan as Howard Rogerson, Beth's father

- Lois Smith as Martha, Dan's secretary

- Mike Nussbaum as Bob Drimmer

- J. J. Johnston as O'Rourke

- Michael Arkin as Lieutenant

- Jane Krakowski as Christine, the babysitter

Production

Writing

The film was adapted by James Dearden (with some help from Nicholas Meyer[2]) from Diversion, an earlier 1980 short film by Dearden for British television. In Meyer's book "The View from the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood", he explains that in late 1986 producer Stanley R. Jaffe asked him to look at the script developed by Dearden, and he wrote a four-page memo making suggestions for the script including a new ending for the movie. A few weeks later he met with director Adrian Lyne and gave him some additional suggestions. Ultimately Meyer was asked to redraft the script on the basis of his suggestions, which ended up being the shooting script.

Casting

Producers Sherry Lansing and Stanley Jaffe both had serious doubts about casting Glenn Close because they didn't think she could be sexual enough for the role of Alex.[3] Close was persistent, so that after meeting with Jaffe several times in New York, she was asked to fly out to Los Angeles to read with Michael Douglas in front of Adrian Lyne and Lansing. Before the audition, she let her naturally frizzy hair "go wild" because she was impatient at putting it up, and she wore a slimming black dress she thought made her look "fabulous" to audition.[4] This impressed Lansing, because Close "came in looking completely different...right away she was into the part."[5] Close and Douglas performed a scene from early in the script, where Alex flirts with Dan in a café, and Close came away "convinced my career was over, that I was finished, I had completely blown my chances."[3] Lansing and Lyne, however, were both convinced that she was right for the role; Lyne stated that "an extraordinary erotic transformation took place. She was this tragic, bewildering mix of sexuality and rage—I watched Alex come to life.”[6]

To prepare for her role, Glenn Close consulted several psychologists, hoping to understand Alex's psyche and motivations. She was uncomfortable with the bunny boiling scene, which she thought was too extreme, but she was assured on consulting the psychologists that such an action was entirely possible and that Alex's behavior corresponded to someone who had experienced incestual sexual abuse as a child.[3]

Alternate ending

Alex Forrest was originally scripted slashing her throat at the film's end with the knife Dan had left on the counter, so as to make it appear that Dan had murdered her. After seeing her husband being taken away by police, Beth finds a revealing cassette tape that Alex sent Dan in which she threatens to kill herself. Upon realizing Alex's intentions, Beth takes the tape to the police, which acquits Dan of the murder. The last scene shows, in flashback, Alex taking her own life by slashing her throat while listening to Madame Butterfly.

After doing test screenings, Joseph Farrell (who handled the test screenings) suggested Paramount to reshoot a new ending.[7][8] Alex was killed by a gunshot during the three-week reshoot of the action scene. Alex's murder by Beth juxtaposes the relationship between the two characters; with Alex being victimized and Beth violently protecting her family.[9]

In the 2002 Special Edition DVD, Close comments that she had doubts about re-shooting the film's ending because she believed the character would "self-destruct and commit suicide".[9] Close eventually gave in on her concerns, and filmed the new sequence after having fought against the change for two weeks.[9] Close has described how protective she was of her character, whom she "never thought of as a villain",[10] stating that: "I wasn't playing a generality, I wasn't playing a cliché. I was playing a very specific, deeply disturbed, fragile human being, whom I had grown to love."[3] However, though the ending made Alex into a "psychopath" against Close's wishes, she has also acknowledged that the film would not have experienced the enormous success it did without the new ending, because it gave the audience "...a sense of catharsis, a hope, that somehow the family unit would survive the nightmare." [3]

The film was initially released in Japan with the original ending. The original ending also appeared on a special edition VHS and LaserDisc release by Paramount in 1992, and was included on the film's DVD release a decade later.[11]

Roles

In the earlier phase of the film, when it was under the title Diversion, Alex committed suicide in the end. After showing this version to a test audience, they felt this was not a good enough way for Alex to go. Instead, the producers decided to shoot the last scene as a more vengeful and violent death for Alex.[12] Close has spoken of the decision to change the ending as "a terrible betrayal of the character that I created...I desperately wanted to remind the audience that this character was more self-destructive than destructive."

After spending $1.3 million, Alex's death and Beth's survival was determined to be the official ending of the film. However, this presented a more traditionalist message to the audience. This new ending gave the idea that a professional woman and a wife/mother are two very divided choices. With Alex being shot by Beth, in the official ending of the film, this is viewed as death to the bad woman (a career woman), and a win for the good woman (a wife/mother).[12] Close insisted on adding the shot in the confrontation scene where Alex mutilates her own leg with a kitchen knife to show that she was "as self-destructive as she was aggressive".[3] However, according to Close, "the image of Alex wielding that knife was too horrifying for any subtle nuance, and it transformed her into a psychopath as a result. And she became the most hated woman in America."[3]

Reception

After its release, Fatal Attraction engendered much discussion of the potential consequences of infidelity. Some feminists, meanwhile, did not appreciate what they felt was the depiction of a strong career woman who is at the same time psychopathic.[9] Feminist Susan Faludi discussed the film in Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, arguing that major changes had been made to the original plot in order to make Alex wholly negative, while Dan's carelessness and the lack of compassion and responsibility raised no discussion, except for a small number of fundamentalist men's groups who said that Dan was eventually forced to own up to his irresponsibility in that "everyone pays the piper".[13]

Feminist scholars have also stated that in many ways the film has used its correlation of career woman to psychopathy in order to create its horror element. As described by Deborah Jermyn, the use of the "monstrous-feminine" as a tool in the 1980s horror genre was a way to portray a man's worst fears', where a woman has rejected familial values and reverted to hysteria, questioning the true values of woman and what it means to be feminine.[14] There are also many ways that Alex (Close) portrays womanhood in a more traditional light, with the character befriending her lover's wife and drinking tea in their home, while contrastingly, his wife slowly turns more assertive and violent. The fluidity of these female characters' monstrous and fearful tendencies is what makes the "fear" more real, according to feminist study. The fact that a woman who rejects traditional womanhood for a more career-based lifestyle can swap in just a matter of moments to the "housewife", and vice-versa provides the horror that this movie begs. Women feared both becoming this career-driven "monster" and being the oblivious housewife, while men feared that their companion could in fact be both of these things at once.

The film has left an indelible impression on male viewers. Close was quoted in 2008 as saying, "Men still come up to me and say, 'You scared the shit out of me.' Sometimes they say, 'You saved my marriage.'"[15]

The film spent eight weeks at #1 in the U.S. and eventually grossed $156.6 million domestically, making the film the second-highest-grossing film of 1987 in the U.S. behind Three Men and a Baby. It also grossed $163.5 million overseas for a total gross of $320.1 million, making it the biggest film of 1987 worldwide.[16] This in turn led to several similarly-themed psychological thrillers being made throughout the late 1980s and 1990s.

Overall, the film received positive reviews from critics. Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 78% based on reviews from 46 critics, with the site's consensus "A potboiler in the finest sense, Fatal Attraction is a sultry, juicy thriller that's hard to look away from once it gets going."[17] On Metacritic, the film has a rating of 67/100 based on reviews from 16 critics.[18]

Academic analysis

The character of Alex Forrest has been discussed by psychiatrists and film experts, and has been used as a film illustration for the condition borderline personality disorder.[19] The character displays the behaviors of impulsivity, emotional lability, frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, frequent severe anger, self-harming, and changing from idealization to devaluation; these traits are consistent with the diagnosis, although generally aggression to the self rather than others is a more common feature in borderline personality disorder.[20] Some have instead considered the character to be a psychopath.[9]

As referenced in Orit Kamirs' Every Breath You Take: Stalking Narratives and the Law, "Glenn Close's character Alex is quite deliberately made to be an erotomaniac. Gelder reports that Glenn Close 'consulted three separate shrinks for an inner profile of her character, who is meant to be suffering from a form of obsessive condition known as de Clérambault's syndrome' (Gelder 1990, 93—94)".[21]

The popular term "bunny boiler", often used to describe an obsessive, spurned woman, derives from the scene where it is discovered that Alex has boiled the pet rabbit.[22][23]

Mental health and gender

As Alex Forrest is portrayed as a psychotic, love-obsessed woman seeking revenge, behaviors that represent stalking are present. According to a study of 148 people conducted by Randy and Lori Sansone, over half of the people who were found guilty of stalking-related incidents also experienced borderline personality disorder among other mental health concerns. It can be noted that Alex Forrest's femininity was seen as toxic and fearful to the people in the film that she interacted with, which is a crucial representation of women as possessive and psychotic when it comes to dominance over a man. People who experience borderline personality disorder can also have higher risks of issues like bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.[24]

Further, most stalking situations occur from people who were previously involved in relationships with the person who is being stalked, according to research by Spitzberg and Vekslet.[25] In the case of Alex Forrest, her obsession was for a man that she could not have due to other circumstances in his life. These circumstances, Beth and Ellen, are his family, and though Alex and Dan did not have a deep or meaningful relationship, Alex's clinginess caused assumptions of mental health issues.

Alex's representation of poor mental health in this film shows exactly the clinginess and attachment that people with stalking behaviors present. Slitting her wrists and pretending to be pregnant are manipulative techniques that someone with a personality and attachment disorder would use to regain the desired intimacy with a former partner. Women tend to stalk former partners as well as the women associated with those former partners, much like one can see in the 1992 film Single White Female.[26]

Awards

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Picture | Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing | Nominated |

| Best Director | Adrian Lyne | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | James Dearden | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Glenn Close | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Anne Archer | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Michael Kahn Peter E. Berger |

Nominated | |

| ACE Eddie | Best Edited Feature Film | Nominated | |

| ASCAP Award | Top Box Office Films | Maurice Jarre | Won |

| BAFTA Awards | Best Actor | Michael Douglas | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actress | Anne Archer | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Michael Kahn and Peter E. Berger | Won | |

| Casting Society of America | Best Casting for Feature Film, Drama | Risa Bramon Garcia | Nominated |

| Billy Hopkins | Nominated | ||

| David di Donatello | Best Foreign Actor | Michael Douglas | Nominated |

| Best Foreign Actress | Glenn Close | Nominated | |

| Directors Guild of America | Outstanding Directing – Feature Film | Adrian Lyne | Nominated |

| DVD Exclusive Award | Original Retrospective Documentary, Library Release | Jon Barbour | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Stanley R. Jaffe | Nominated |

| Sherry Lansing | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | Adrian Lyne | Nominated | |

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Glenn Close | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture | Anne Archer | Nominated | |

| Goldene Kamera | Golden Camera for Best International Actor | Michael Douglas | Won |

| Golden Camera for Best International Actress | Glenn Close | Won | |

| Golden Screen | Won | ||

| Grammy Award | Best Album Written for a Motion Picture or Television | Maurice Jarre | Nominated |

| NBR Award | Top Ten Films | Won | |

| People's Choice Award | Favorite Dramatic Motion Picture | Won | |

| Writers Guild of America | Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium | James Dearden | Nominated |

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills—#28[27]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains: Alex Forrest—Villain—#7[28]

Home media

A Special Collector's Edition of the film was released on DVD in 2005.[29] Paramount released Fatal Attraction on Blu-ray Disc on June 9, 2009.[30] The Blu-ray release contained several bonus features from the 2005 DVD, including commentary by director Adrian Lyne, cast and crew interviews, a look at the film's cultural phenomenon, a behind-the-scenes look, rehearsal footage, the alternative ending, and the original theatrical trailer.

In other media

Play

A play based on the movie opened in London's West End at the Theatre Royal Haymarket in March 2014.[31] It was adapted by the movie's original screenwriter James Dearden.[32]

TV series

On July 2, 2015, Fox announced that a TV series based on the film is being developed by Mad Men writers Maria and Andre Jacquemetton.[33] On January 13, 2017, it was announced that the project was canceled.[34]

See also

References

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ↑ Meyer, Nicholas (2009). The View from the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood. Penguin Books. ISBN 9781101133477.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Oxford Union (2018-05-04). Glenn Close Full Address & Q&A Oxford Union. YouTube.com. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ↑ Jess Cagle (2011-10-07). "From the archives: Fatal Attraction's Glenn Close, Michael Douglas reunite". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ↑ Fatal Attraction (1987) The Making Of Part 1 & 2. YouTube.com. 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ↑ James S. Kunen (1987-10-26). "The Dark Side of Love". People Magazine. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/26/business/joseph-farrell-dies-at-76-used-market-research-to-shape-films.html

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/1999/nov/07/magazine/tm-30884

- 1 2 3 4 5 Remembering Fatal Attraction 2002 DVD Special Features

- ↑ Fatal Attraction Reunion Interview. YouTube.com. 2010-03-06. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction (Special Collector's Edition) (1987)". Amazon (United States). Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- 1 2 Bromley, Susan; Hewitt, Pamela (1992). "Fatal Attraction: The Sinister side of Women's Conflict about Career and Family". The Journal of Popular Culture. 26 (3): 17–23. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1992.2603_17.x.

- ↑ See "Fatal and Foetal Visions: The Backlash in the Movies", Chapter 5 of Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, published by Chatto & Windus, 1991

- ↑ Jermyn, D (1996). "Rereading the bitches from hell: A feminist appropriation of the female psychopath". Screen. 37 (3): 251–67. doi:10.1093/screen/37.3.251.

- ↑ "Close says boiling that bunny saved marriages". The Times. 2008-01-06. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction Reviews". Metacritic. 18 September 1987.

- ↑ Robinson, David J. (1999). The Field Guide to Personality Disorders. Rapid Psychler Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-9680324-6-X.

- ↑ Wedding D, Boyd MA, Niemiec RM (2005). Movies and Mental Illness: Using Films to Understand Psychopathology. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe. p. 59. ISBN 0-88937-292-6.

- ↑ Kamir, Orit (2001). Every Breath You Take: Stalking Narratives and the Law. University of Michigan Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-472-11089-6.

- ↑ Singh, Anita. "Fatal Attraction: My sympathy for the bunny-boiler". The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "The meaning and origin of the expression: Bunny boiler". phrases.org.uk.

- ↑ Sansone, R. A; Sansone, L. A (2010). "Fatal attraction syndrome: Stalking behavior and borderline personality". Psychiatry. 7 (5): 42–6. PMC 2882283. PMID 20532158.

- ↑ Spitzberg, B. H; Veksler, A. E (2007). "The personality of pursuit: Personality attributions of unwanted pursuers and stalkers". Violence and victims. 22 (3): 275–89. PMID 17619634.

- ↑ Purcell, Rosemary; Pathé, Michele; Mullen, Paul E (2001). "A Study of Women Who Stalk". American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (12): 2056–60. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2056. PMID 11729025.

- ↑ "America's Most Heart-Pounding Movies" (PDF). AFI. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains". AFI. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction (Special Collector's Edition) [DVD] (2005)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction [Blu-ray]". Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ "Fatal Attraction and Strangers On A Train head to West End stage". bbc.co.uk/news. BBC News. 20 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ "'Fatal Attraction' to become a stage play, will debut in London". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ Leane, Rob. "Fatal Attraction TV series in development". denofgeek.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ http://deadline.com/2017/01/fatal-attraction-remake-dead-fox-1201885804/

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fatal Attraction |