Bullitt

| Bullitt | |

|---|---|

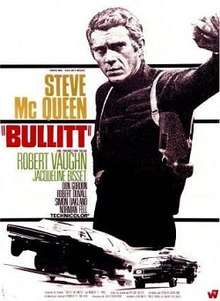

Film poster by Michel Landi | |

| Directed by | Peter Yates |

| Produced by | Philip D'Antoni |

| Screenplay by |

Alan R. Trustman Harry Kleiner |

| Based on |

Mute Witness by Robert L. Fish |

| Starring |

Steve McQueen Robert Vaughn Jacqueline Bisset |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

| Cinematography | William A. Fraker |

| Edited by | Frank P. Keller |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.-Seven Arts |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million[1] |

| Box office | $42.3 million[2] |

Bullitt is a 1968 American thriller film directed by Peter Yates and produced by Philip D'Antoni. The picture stars Steve McQueen, Robert Vaughn, and Jacqueline Bisset.[3] The screenplay by Alan R. Trustman and Harry Kleiner was based on the 1963 novel, Mute Witness,[4][5][6][7] by Robert L. Fish, writing under the pseudonym Robert L. Pike.[8][9] Lalo Schifrin wrote the original jazz-inspired score, arranged for brass and percussion. Robert Duvall has a small part as a cab driver who provides information to McQueen.

The film was made by McQueen's Solar Productions company, with his partner Robert E. Relyea as executive producer. Released by Warner Bros.-Seven Arts on October 17, 1968, the film was a critical and box-office smash, later winning the Academy Award for Best Film Editing (Frank P. Keller) and receiving a nomination for Best Sound. Writers Trustman and Kleiner won a 1969 Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America for Best Motion Picture Screenplay. Bullitt is also notable for its car chase scene through the streets of San Francisco, which is regarded as one of the most influential in movie history.[10][11][12][13]

In 2007, Bullitt was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[14]

Plot

Ambitious San Francisco politician Walter Chalmers is about to present a surprise star witness in a Senate subcommittee hearing on organized crime. Johnny Ross, a defector from the Organization in Chicago, is to be put under protective custody over the weekend until his Monday morning appearance. Seeking to associate himself and his grandstanding mob-busting effort with a high-visibility SFPD detective, Chalmers requests Lieutenant Frank Bullitt be put in charge. Bullitt and his team, Delgetti and Stanton, put Ross under around-the-clock protection in a cheap hotel selected by Chalmers. After Delgetti goes off shift, Stanton is on solo duty when the desk clerk unexpectedly calls at 1:00 a.m., Saturday morning to announce that Chalmers and an unidentified man want to come up. While Stanton checks by phone with Bullitt, Ross unchains the hotel room door. Two hitmen burst in and shoot Stanton and Ross, seriously wounding both occupants.

At the hospital, Chalmers holds Bullitt responsible. Later, Bullitt thwarts a second assassination attempt on Ross before it can materialize, but Ross soon dies of his original wounds. Helped by a sympathetic Dr. Willard, who had been snubbed by Chalmers, Bullitt delays news of the death by spiriting the body out of the hospital by private ambulance service, registering it as a John Doe at the city morgue. Bullitt finds the cab driver who drove Ross to the hotel, and recreates Ross' movements upon arriving in town, learning that he made a long distance call from a phone booth. Bullitt's confidential informant, Eddy, reveals that Ross was caught stealing $2 million ($14.1 million today) from the Chicago mob and fled to San Francisco after escaping an attempted hit in Chicago. Meanwhile, Chalmers serves Bullitt's captain with a writ of habeas corpus to force Bullitt to produce Ross.

While driving in San Francisco, Bullitt is pursued by the hitmen in a 1968 Dodge Charger R/T. He flips the chase, turning the hunters into the hunted. They attempt to escape, and a high-speed chase ensues through the steep streets of Russian Hill (actually a composite location combined with Potrero Hill) and out onto the highway, ending when Bullitt's 1968 Ford Mustang GT forces the Charger off the road and into a gas station, where it explodes in a huge fireball.

Bullitt and Delgetti face their superiors on Sunday morning. They reveal that Ross is dead and their only leads are phone records showing Ross's call was to a Dorothy Simmons in a hotel in nearby San Mateo. The detectives are given until Monday to deliver results. With his car out of commission, Bullitt gets a ride from his girlfriend Cathy in her Porsche 356. The detectives find Simmons strangled in her hotel room. Cathy sees police rushing in and follows, fearing for Bullitt. Horrified by the crime scene, she later confronts him about his violent world, wondering whether she really understands him and where the life he leads will take them.

Back in San Francisco, Bullitt and Delgetti search Simmons' luggage, discovering brand new sets of clothing, an airline ticket and passport folders, a travel brochure for Rome, and thousands of dollars in traveler's checks made out to an Albert and Dorothy Renick. Bullitt requests passport information for the Renicks and a fingerprint check for the dead Ross. Chalmers again confronts Bullitt, demanding a signed admission that Ross died while in his custody. But Bullitt refuses to comply. A facsimile of Albert Renick's passport application arrives, showing the man they believed to be Ross was actually Renick, a used car salesman from Chicago with no criminal record bearing a startling resemblance to Ross. Bullitt points out that Chalmers was duped by the real Ross, who used him to fake his own death by setting up Renick to die in his place, then murdered the wife to complete the cover-up.

Delgetti discovers reservations for the Renicks on an evening flight to Rome. He and Bullitt go to San Francisco International Airport to look for Ross, traveling as Renick. They stake out the Rome flight gate, only to find that Ross has switched to a slightly earlier flight to London that is already taxiing toward takeoff. Chalmers shows up to lay claim to his witness, even though he is now wanted for murder, and is again rebuffed by Bullitt. Bullitt has the plane stopped, but Ross escapes by jumping out the rear cabin door. Bullitt jumps as well, and a foot chase across the busy runways ends in a tense pursuit inside the crowded passenger terminal. When Ross bolts and shoots a security guard, Bullitt shoots and kills Ross. The empty-handed Chalmers skulks away, and is driven off in his limousine bearing a "Support Your Local Police" bumper sticker.

Early the next morning, Bullitt walks home and observes Cathy's car upon approaching his apartment. He looks in and sees her sleeping in his bedroom, but does not wake her. He takes off his shoulder holster and balances it on a banister. As he begins to wash up at the bathroom sink, he looks up into his own reflection and contemplates himself for a long moment.

Cast

- Steve McQueen as Lt. Frank Bullitt

- Don Gordon as Delgetti

- Robert Vaughn as Walter Chalmers

- Simon Oakland as Captain Sam Bennett

- Felice Orlandi as Albert "Johnny Ross" Renick

- Pat Renella as Johnny Ross

- Jacqueline Bisset as Cathy

- Carl Reindel as Carl Stanton

- Paul Genge as Mike, The Hitman

- Bill Hickman as Phil, The Hitman's Partner

- Robert Duvall as Weissberg (cab driver)

- Norman Fell as Captain Baker

- Georg Stanford Brown as Dr. Willard

- Justin Tarr as Eddy the Informant

- Al Checco as Desk Clerk

- Victor Tayback as Pete Ross

- Robert Lipton as Chalmers' 1st Aide

- Ed Peck as Westcott (reporter at hospital)

- John Aprea as Killer

Production

Bullitt was co-produced by McQueen's Solar Productions and Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, the film pitched to Jack L. Warner as "doing authority differently."[15]

Development

Bullitt was director Yates' first American film. He was hired after McQueen saw his 1967 UK feature, Robbery, with its extended car chase.[16] Joe Levine, whose Embassy Pictures had distributed Robbery, didn't much like it, but Alan Trustman, who saw the picture the very week he was writing the Bullitt chase, insisted that McQueen, Relyea and D'Antoni (none of whom had ever heard of Yates) see Robbery and consider Yates as director for Bullitt.

Casting

McQueen based the character of Frank Bullitt on San Francisco Inspector Dave Toschi, with whom he worked prior to filming.[17][18] McQueen even copied Toschi's unique "fast draw" shoulder holster. Toschi later became famous, along with Inspector Bill Armstrong, as the lead San Francisco investigators of the Zodiac Killer murders that began shortly after the release of Bullitt. Toschi is played by Mark Ruffalo in the film Zodiac, in which Paul Avery (Robert Downey Jr.) mentions that "McQueen got the idea for the holster from Toschi".[18][19]

Realism

Bullitt is notable for its extensive use of actual locations rather than studio sets, and its attention to procedural detail, from police evidence processing to emergency room procedures. Director Yates' use of the new lightweight Arriflex cameras allowed for greater flexibility in location shooting.[20]

Car chase

At the time of the film's release, the car chase scene generated prodigious excitement.[10] Leonard Maltin has called it a "now-classic car chase, one of the screen's all-time best."[11] Emanuel Levy wrote in 2003 that, "Bullitt contains one of the most exciting car chases in film history, a sequence that revolutionized Hollywood's standards."[12] In his obituary for Peter Yates, Bruce Weber wrote, "Mr. Yates’ reputation probably rests most securely on Bullitt (1968), his first American film – and indeed, on one particular scene, an extended car chase that instantly became a classic."[13] The editing of this scene likely won editor Frank P. Keller the Academy Award for Best Editing.[21]

Filming

The chase scene starts at 1h:05m into the film. The total time of the scene is 10 minutes and 53 seconds, beginning in the Fisherman's Wharf area of San Francisco, at Columbus and Chestnut (although Bullitt first notices the hitmen following his car while driving west on Army, now Cesar Chavez, just after passing under Highway 101), followed by Midtown shooting on Hyde and Laguna Streets, with shots of Coit Tower and locations around and on Filbert and University Streets. The scene ends outside the city at the Guadalupe Canyon Parkway in Brisbane.[22] The route is geographically impossible to take place in real time.[23]

Two 1968 390 V8 Ford Mustang GT Fastbacks (325 hp) with four-speed manual transmissions were used for the chase scene, both lent by the Ford Motor Company to Warner Bros. as part of a promotional agreement. The Mustangs' engines, brakes and suspensions were heavily modified for the chase by veteran car racer Max Balchowsky. Ford also originally lent two Galaxie sedans for the chase scenes, but the producers found the cars too heavy for the jumps over the hills of San Francisco. They were replaced with two 1968 375 hp 440 Magnum V8-powered Dodge Chargers. The engines in both Charger models were left largely unmodified, but the suspensions were mildly upgraded to cope with the demands of the stunt work.

The director called for maximum speeds of about 75–80 miles per hour (121–129 km/h), but the cars (including the chase cars filming) at times reached speeds of over 110 miles per hour (180 km/h). Driver's point-of-view shots were used to give the audience a participant's feel of the chase. Filming took three weeks, resulting in nine minutes and 42 seconds of pursuit. Multiple takes were spliced into a single end product resulting in discontinuity: heavy damage on the passenger side of Bullitt's car can be seen much earlier than the incident producing it, and the Charger appears to lose five wheel covers, with different ones missing in different shots. Shooting from multiple angles simultaneously and creating a montage from the footage to give the illusion of different streets also resulted in the speeding cars passing the same vehicles at several different times, including, widely noted, a green Volkswagen Beetle.[24] At one point the Charger crashes into the camera in one scene and the damaged front fender is noticeable in later scenes. Local authorities did not allow the car chase to be filmed on the Golden Gate Bridge, but did permit it in Midtown locations including Bernal Heights and the Mission District, and on the outskirts of neighboring Brisbane.[25]

McQueen, an accomplished driver, drove in the close-up scenes, while stunt coordinator Carey Loftin, stuntman and motorcycle racer Bud Ekins, and McQueen's usual stunt driver, Loren Janes, drove for the high-speed part of the chase and performed other dangerous stunts.[26] Ekins, who doubled for McQueen in The Great Escape sequence where McQueen's character jumps over a barbed wire fence on a motorcycle, lays one down in front of a skidding truck during the Bullitt chase. The Mustang's interior rear view mirror goes up and down depending on who is driving: when the mirror is up, McQueen is visible behind the wheel, when it is down, a stunt man is driving.

The black Dodge Charger was driven by veteran stunt driver Bill Hickman, who played one of the hitmen and helped with the chase scene choreography. The other hitman was played by Paul Genge, who played a character who had ridden a Dodge off the road to his death in an episode of Perry Mason ("The Case of the Sausalito Sunrise") two years earlier. In a magazine article many years later, one of the drivers involved in the chase sequence remarked that the Charger – with a larger engine (big-block 440 cu. in. versus the 390 cu. in.) and greater horsepower (375 versus 325) – were so much faster than the Mustang that the drivers had to keep backing off the accelerator to prevent the Charger pulling away from the Mustang.[25]

Editing

The editing of the car chase likely won Frank P. Keller the editing Oscar for 1968,[21] and has been included in lists of the "Best Editing Sequences of All-Time".[27] Paul Monaco has written, "The most compelling street footage of 1968, however, appeared in an entirely contrived sequence, with nary a hint of documentary feel about it – the car chase through the streets of San Francisco in Bullitt, created from footage shot over nearly five weeks. Billy Fraker, the cinematographer for the film, attributed the success of the chase sequence primarily to the work of the editor, Frank P. Keller. At the time, Keller was credited with cutting the piece in such a superb manner that he made the city of San Francisco a "character" in the film."[28] The editing of the scene was not without difficulties; Ralph Rosenblum wrote in 1979 that "those who care about such things may know that during the filming of the climactic chase scene in Bullitt, an out-of-control car filled with dummies tripped a wire which prematurely sent a costly set up in flames, and that editor Frank Keller salvaged the near-catastrophe with a clever and unusual juxtaposition of images that made the explosion appear to go off on time."[29] This chase scene has also been cited by critics as groundbreaking in its realism and originality.[30] In the release print and the print shown for many years, a scene in which the Charger actually hits the camera causing a red flare on screen, which many feel added to the realism, was edited out on DVD prints to the disappointment of many fans.

Music

The original score was composed by Lalo Schifrin. The tracks on the soundtrack album are alternative versions of those heard in the film, re-recorded by Schifrin with leading jazz musicians, including Bud Shank (flute), Ray Brown (bass), Howard Roberts (guitar) and Larry Bunker (drums).[31]

In 2000, the original arrangements as heard in the movie were recreated by Schifrin in a recording session with the WDR Big Band in Cologne, Germany, and released on the Aleph label.[32] This release also includes re-recordings of the 1968 soundtrack album arrangements for some tracks.

In 2009, the never-before-released original recording of the score heard in the movie, recorded by Schifrin on the Warner Bros. scoring stage with engineer Dan Wallin, was made available by Film Score Monthly. Some score passages and cues are virtually identical to the official soundtrack album, while many softer, moodier cues from the film were not chosen or had been rewritten for the soundtrack release. Also included are additional cues that didn't make it into the film. In addition, the two-CD set features the official soundtrack album, newly mixed from the 1" master tape.[31]

In the restaurant scene with McQueen and Bissett, the live band playing in the background is Meridian West, a jazz quartet that McQueen had seen performing at famous Sausalito restaurant, The Trident.[33]

Release

Bullitt garnered both critical acclaim and box office success.

Box office performance

Produced on a $5.5 million budget, the film grossed over $42.3 million in the US,[2] making it the 5th highest-grossing film of 1968.

Critical reception

Bullitt was well received by critics and is considered by some to be one of the best films of 1968.[34][35][36] At the time, Renata Adler made the film a New York Times Critics' Pick, calling it a "terrific movie, just right for Steve McQueen –-fast, well acted, written the way people talk." According to Adler, "the ending should satisfy fans from Dragnet to Camus."[37]

In 2004, The New York Times placed the film on its list of The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made.[30] In 2011, Time magazine listed it among "The 15 Greatest Movie Car Chases of All Time," describing it as "the one, the first, the granddaddy, the chase on the top of almost every list," and saying "Bullitt‘s car chase is a reminder that every great such scene is a triumph of editing as much as it is stunt work. Naturally, it won that year's Academy Award for Best Editing".[38] Among 21st-century critics, it holds a 97% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, representing positive reviews from 34 of 35 critics with an average rating of 7.7/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Steve McQueen is cool as ice in this thrilling police procedural that also happens to contain the arguably greatest car chase ever."[39]

Awards and honors

The film was nominated for and won several critical awards.[40] Frank P. Keller won the 1969 Academy Award for Best Film Editing, and it was also nominated for Best Sound.[41] Five nominations at the BAFTA Film Awards for 1969 included Best Director for Peter Yates, Best Supporting Actor for Robert Vaughn, Best Cinematography for William A. Fraker, Best Film Editing for Frank P. Keller, and Best Sound Track. Robert Fish, Harry Kleiner, and Alan Trustman won the 1969 Edgar Award for Best Motion Picture.[42] Keller won the American Cinema Editors Eddie Award for Best Edited Feature Film. The film also received the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Cinematography (William A. Fraker) and the Golden Reel Award for Best Sound Editing – Feature Film. It was successful at the 1970 Laurel Awards, winning Golden Laurel awards for Best Action Drama, Best Action Performance (Steve McQueen) and Best Female New Face (Jacqueline Bisset). In 2000, the Society of Camera Operators awarded Bullitt its "Historical Shot" award to David M. Walsh.

Legacy

The famous car chase was later spoofed in Peter Bogdanovich's screwball comedy film, What's Up, Doc?, the Clint Eastwood film, The Dead Pool, in the Futurama episode, "Bendin' in the Wind," and in the Archer season six episode, "The Kanes." Bullitt producer Philip D'Antoni went on to film two more car chases, for The French Connection and The Seven-Ups, both set and shot in New York City.

The Ford Mustang name has been closely associated with the film. In 2001, the Ford Motor Company released the Bullitt edition Ford Mustang GT.[43] Another version of the Ford Mustang Bullitt, which is closer to resembling the original film Mustang, was released in 2008, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the film.[44][45] A third version is planned for 2019.[46] In 2009, Bud Brutsman of Overhaulin' built an authentic-looking replica of the Bullitt Mustang, fully loaded with modern components, for the five-episode 2009 TV series, Celebrity Rides: Hollywood's Speeding Bullitt, hosted by Chad McQueen, son of Steve McQueen.[47][48]

Steve McQueen's likeness as Frank Bullitt was used in two Ford commercials. The first was for the Europe-only 1997 Ford Puma, which featured a special effects montage of McQueen (who died in 1980) driving a new Puma around San Francisco before parking it in a studio apartment garage beside the film Mustang and the motorcycle from The Great Escape.[49] In a 2004 commercial for the 2005 Mustang, special effects are again used to create the illusion of McQueen driving the new Mustang, after a man receives a Field of Dreams-style epiphany and constructs a racetrack in the middle of a cornfield.[50]

The Mustang is featured in the 2003 video game, Ford Racing 2, in a Drafting challenge, on a course named Port Side. It appears in the Movie Stars category, along with other famous cars like the Ford Torino from Starsky & Hutch and the Ford Mustang Mach 1 from Diamonds Are Forever.[51][52] In the 2011 video game, Driver: San Francisco, the "Bite the Bullet" mission is based on the famous chase scene, with licensed versions of the Mustang and Charger from the film.[53]

In the opening scene of 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003), the main protagonist, Brian O'Conner (Paul Walker), is called "Bullitt" by his friends Suki (Devon Aoki) and Tej Parker (Chris Bridges).

During the only season of the 2012 TV series Alcatraz, Det. Rebecca Madsen (Sarah Jones) drives a green 1968 390 V8 Ford Mustang fastback like Bullitt's. In the series finale, she finds herself in a 2013 Ford Mustang GT, the modern equivalent of the 1968 fastback, giving chase to a black LX Dodge Charger driven by series antagonist Thomas "Tommy" Madsen (David Hoflin). The sequence pays homage to Bullitt's car chase, including Madsen buckling the seatbelt in his Charger before starting, and two passes by a green Volkswagen Beetle.

The Blue Bloods TV series 2015 episode "The Bullitt Mustang" centers around the reported theft of one of the Mustangs used in the film, valued at a half million dollars, a case which detectives Danny Reagan and Maria Baez pick up.

Several items of clothing worn by McQueen's Bullitt received a boost in popularity thanks to the film: desert boots, a trench coat, a blue turtleneck sweater and, most famously, a brown tweed jacket with elbow patches.[54]

The last remaining Charger and one of the two Mustangs were scrapped after filming because of damage and liability concerns, while the other was sold to an employee of Warner Bros.[55] The car changed hands several times, with McQueen at one point making an unsuccessful attempt to buy it in late 1977.[56] The car is currently owned by Sean Kiernan in Tennessee whose father bought the car for $6,000 in 1974 after responding to a listing in Road & Track.[46] The stunt Mustang used for filming was found in 2016 at a junkyard in Mexico. The car was verified by an automobile authentication expert who conclusively determined from the vehicle's VIN and other identifying information.[57]

See also

References

- ↑ British Director to Film U.S. Dilemma Lesner, Sam. Los Angeles Times 9 Feb 1968: c14.

- 1 2 "Box Office Information for Bullitt". The Numbers. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Bullitt". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ↑ Monush 2009, p. 274.

- ↑ Eagan 2009, p. 641.

- ↑ Eliot, Marc (2011). Steve McQueen: A Biography (1st ed.). New York City: Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-0307453211.

- ↑ Murphy 1999, p. 179.

- ↑ Pike, Robert L. (1963). Mute Witness. New York City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-9997527875.

- ↑ Kabatchnik 2012, p. 231.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (December 23, 1968). "Bullitt". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

"Bullitt," as everybody has heard by now, also includes a brilliant chase scene. McQueen (doing his own driving) is chased by, and chases, a couple of gangsters up and down San Francisco's hills. They slam into intersections, bounce halfway down the next hill, scrape by half a dozen near-misses, sideswipe each other, and leave your stomach somewhere in the basement for about 11 minutes.

- 1 2 Maltin, Leonard, ed. (2004). Leonard Maltin's 2004 Movie and Video Guide. Penguin Group. p. 195.

Taut action-film makes great use of San Francisco locations, especially in now-classic car chase, one of the screen's all-time best; Oscar-winning editing by Frank Keller.

- 1 2 Levy, Emanuel (2008). "Bullitt". emanuellevy.com. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- 1 2 Weber, Bruce (January 11, 2011). "Peter Yates, Filmmaker, Is Dead at 81". The New York Times.

- ↑ "National Film Registry 2007". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Sandford 2003, p. 224.

- ↑ Jessica Winter; Lloyd Hughes; Richard Armstong; Tom Charity (2007). The Rough Guide to Film. Rough Guides Limited. p. 618. ISBN 1843534088.

- ↑ Steve McQueen – The Making Of Bullitt, 1968 Warner Bros. promotional short film.

- 1 2 Graysmith, Robert. (1986). Zodiac, p. 96. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-89895-9

- ↑ IMDB The Zodiac

- ↑ Eagan 2009, pp. 641–642.

- 1 2 Hartl, John. "Top 10 car chase movies". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 2010-09-16. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

Bullitt (1968). Philip D’Antoni, who went on to produce The French Connection, warmed up for it with this Steve McQueen crime drama, set in San Francisco, where the steep hills seem to yearn for cars to go sailing over them. The director, Peter Yates, makes the most of the locations, especially during a gravity-defying chase sequence that earned an Oscar for its editor, Frank P. Keller.

- ↑ Brebner, Anne; Morrison, John (February 23, 2011). "Aspect Ratio – February 2011" Archived November 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. Blip.tv. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- ↑ Wojdyla, Ben (January 11, 2008). "Bullitt Chase Sequence Mapped, Proves a Tough Route". Jalopnik.com. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- ↑ Cowen, Nick & Hari Patience (September 19, 2008). "Wheels On Film: Bullitt". The Telegraph. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- 1 2 Encinas, Susan (March 1987). "The Greatest Chase of All". Muscle Car Review.

- ↑ Myers, Marc (2011-01-26). "Chasing the Ghosts of 'Bullitt'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ↑ Dirks, Tim. "Best Film Editing Sequences of All-Time, From the Silents to the Present: Part 5". Filmsite.org. AMC Networks.

- ↑ Monaco, Paul (2003). Harpole, Charles, ed. The Sixties. History of the American Cinema. 8. University of California Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-520-23804-4.

- ↑ Rosenblum, Ralph; Karen, Robert (1979). When the Shooting Stops ... The Cutting Begins. Viking Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-670-75991-0.

- 1 2 "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made – Reviews – Movies – New York Times". Nytimes.com. 2003-04-29. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- 1 2 "Bullitt (1968)". Film Score Monthly. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Payne, D. Lalo Schifrin discography accessed July 25, 2013.

- ↑ "By 1968 the group was performing at The Trident, a prominent jazz club in Sausalito and the group became a regular performer at Glide Memorial on Sundays. By March of 1968, Meridian West had been noticed by Steve McQueen, the actor, who was captivated by a performance at The Trident. McQueen gave the group a visual cameo appearance in the movie, "Bullitt," which was being filmed in San Francisco in April." - Meridian Meridian West web site (archived at WebCite). A similar account is available at Meridian West Folk Jazz Ensemble with Allan Pimentel (archived at WebCite).

- ↑ "Greatest Films of 1968". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "The Best Movies of 1968 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1968". IMDb.com. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ Adler, Renata (October 18, 1968). "Bullitt (1968)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ↑ Cruz, Gilbert (May 5, 2011). "The 15 Greatest Movie Car Chases of All Time". Time. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ↑ "Bullitt (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Bullitt Awards and Nominations". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "The 41st Academy Awards (1969) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ↑ "Category List – Best Motion Picture". Edgars Database. Mystery Writers of America. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ The Auto Channel – Ford Mustang Bullitt (2001)

- ↑ 2008 Ford Mustang Bullitt – First Test from Motor Trend

- ↑ Stewart, Ben (November 5, 2007). "Ford Mustang Bullitt Test Drive (with Burnout Video): L.A. Auto Show Preview". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- 1 2 Strassmann, Mark (January 22, 2018). "The return of a Hollywood legend: Steve McQueen's Mustang". CBS News. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ↑ McQueen's '68 "Bullitt" Mustang Tribute Build Archived 2014-05-28 at the Wayback Machine. from BoldRide.com

- ↑ "Celebrity Rides: Hollywood's Speeding Bullitt". TV Guide. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ "A Word from Our Sponsors... Steve McQueen Drives a Puma". TheCathodeRayChoob.com. WordPress. March 4, 2009. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ↑ AutoBlog – Ford Mustang Steve McQueen Ad Revealed from autoblog.com

- ↑ Wilcox, Greg. "Ford Racing 2". Game Tour (Multimedia Empire Inc.). Archived from the original on March 13, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Ford Racing 2 - Amazon.com". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ "The films that influenced Driver: San Francisco". ComputerAndVideoGames. August 10, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ Bonhams Lot 100 From The Chad McQueen Collection: The Bullitt Jacket. Retrieved March 22, 2014. In 1968's Bullitt, McQueen made the most unlikely items extremely fashionable – desert boots, a trench coat, a blue turtleneck sweater and a brown tweed jacket. Only McQueen could make those clothing items ... global trends... The jacket, much like the man, occupies a very special place in cinematic history, it is unquestionably one of the most important pieces of film –and McQueen memorabilia extant. (WebCite archive)

- ↑ Stone, Matt (2007). McQueen's Machines: The Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon. Minneapolis, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7603-38957.

One of the Mustangs was so badly damaged during filming it was judged unrepairable and scrapped. The second, chassis 8R02S125559, was sold to a Warner Bros. employee after filming was completed.

- ↑ "1968 Ford Mustang Fastback (Bullitt – '559)". Historic Vehicle Association. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ↑ Gastelu, Gary (March 6, 2017). "Ford Mustang found in Mexican junkyard is from 'Bullitt,' expert confirms". Fox News. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

Sources

- Monush, Barry (2009). Everybody's Talkin': The Top Films of 1965-1969. Milwaukee: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books. p. 274. ISBN 978-1557836182.

- Eagan, Daniel (2009). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 641–642. ISBN 978-0826418494.

- Murphy, Bruce (1999). Encyclopedia of Murder and Mystery (1st ed.). New York City: St. Martin's Minotaur. p. 179. ISBN 978-0312215545.

- Kabatchnik, Amnon (2012). Blood on the Stage, 1975-2000: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection (1st ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0810883543.

- Sandford, Christopher (2003). McQueen: The Biography. Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-0878333073.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bullitt |

- Bullitt at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Bullitt on IMDb

- Bullitt at the TCM Movie Database

- Bullitt at AllMovie

- Bullitt at the Internet Movie Cars Database

- Bullitt at Box Office Mojo

- Bullitt at Rotten Tomatoes