Brooksville, Florida

| Brooksville, Florida | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| ||

| ||

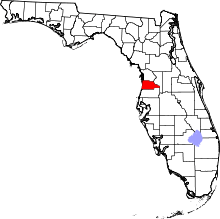

Location in Hernando County and the state of Florida | ||

Brooksville, Florida Location in the United States | ||

| Coordinates: 28°33′13″N 82°23′19″W / 28.55361°N 82.38861°WCoordinates: 28°33′13″N 82°23′19″W / 28.55361°N 82.38861°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Florida | |

| County | Hernando | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 11.28 sq mi (29.22 km2) | |

| • Land | 11.18 sq mi (28.96 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.10 sq mi (0.26 km2) | |

| Elevation | 194 ft (59 m) | |

| Population (2010)[2] | ||

| • Total | 7,719 | |

| • Estimate (2017)[3] | 8,147 | |

| • Density | 728.52/sq mi (281.27/km2) | |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) | |

| Area code(s) | 352 | |

| FIPS code | 12-08800[4] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0279446[5] | |

Brooksville is a city in and the county seat of Hernando County, Florida, United States.[6] As of the 2010 census it had a population of 7,719,[2] up from 7,264 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Brooksville was named in 1856 to honor Preston Brooks, a Democratic congressman from South Carolina. Brooks was an extreme advocate of chattel slavery. In 1856, Massachusetts senator and staunch abolitionist Charles Sumner gave an impassioned speech condemning slavery, in which he insulted Brooks' relative, Senator Andrew Butler. In response, Brooks attacked Sumner with a cane on the floor of Senate, severely injuring him; Brooks did not stop until physically restrained by others.[7] This incident inflamed antebellum tensions throughout the country, emboldened secessionist movements throughout the American south and, eventually, contributed to the outbreak of the American Civil War.[8] Brooksville is home to historic buildings and residences including the home of former Florida Governor William Sherman Jennings and football player Jerome Brown.

Geography

Brooksville is located in east-central Hernando County, 45 miles (72 km) north of Tampa and 51 miles (82 km) southwest of Ocala. The geographic center of Florida is 12 miles (19 km) north-northwest of Brooksville.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Brooksville has a total area of 10.9 square miles (28.3 km2), of which 10.8 square miles (28.1 km2) are land and 0.12 square miles (0.3 km2), or 0.90%, are water.[2]

Brooksville was once a major citrus production area and was known as the "Home of the Tangerine".[9]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 512 | — | |

| 1900 | 641 | 25.2% | |

| 1910 | 979 | 52.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,011 | 3.3% | |

| 1930 | 1,405 | 39.0% | |

| 1940 | 1,607 | 14.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,818 | 13.1% | |

| 1960 | 3,301 | 81.6% | |

| 1970 | 4,060 | 23.0% | |

| 1980 | 5,582 | 37.5% | |

| 1990 | 7,440 | 33.3% | |

| 2000 | 7,264 | −2.4% | |

| 2010 | 7,719 | 6.3% | |

| Est. 2017 | 8,147 | [3] | 5.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

As of Census 2010,[4] there were 7,719 people, 3,504 households, and 1,927 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,469.5 people per square mile (567.7/km2). There were 3,504 occupied housing units at an average density of 793.0 per square mile (306.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.7% White, 19.1% African American, 1% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 2.1% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.6% of the population, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander composed 0.2% of the population.

There were 3,220 households out of which 23.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.9% were married couples living together, 14.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.1% were non-families. 38.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 19.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.14 and the average family size was 2.82.

In the city, 22.1% of people were under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 21.7% from 25 to 44, 18.7% from 45 to 64, and 29.7% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 44 years. For every 100 females, there were 80.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.4 males.

Economy

Personal income

The median income for a household in the city was $25,489, and the median income for a family was $31,060. Males had a median income of $29,837 versus $21,804 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,265. About 16.8% of families and 21.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.9% of those under age 18 and 11.5% of those age 65 or over.

Industry

Tourism

The city hosted an annual Blueberry Festival in downtown Brooksville until 2017[11] with music performances that have included Easton Corbin. The Festival has moved to Plant City since.

The city has historic homes along brick streets. There is also a Native American outpost in a log cabin,[12], the Brooksville Railroad Depot Museum, and The Hernando Heritage Museum, located in the May-Stringer House. The Historic Brooksville Walking/Driving Tour features many historic homes; a guidebook is available at the City of Brooksville website and at the Main library on Howell Avenue.

The first annual GET HEALTHY Brooksville Cycling Classic was held in 2010 and attracted cyclists from all over the state. The Brooksville Business Alliance has sponsored the annual Brooksville Founders Week Celebration since 2006.[13] There is a monthly live music performance, antique car show, and other events.

History

Fort DeSoto, established about 1840 to give protection to settlers from Native Americans, was located at the northeastern edge of present-day Brooksville on Croom Road about one-half mile east of U.S. Highway 41. The fort was also a trading post and a regular stop on the Concord stagecoach line which ran from Palatka to Tampa.

The fort was built on top of a heavy bed of limestone, a fact which they were unaware of at the time, and this made it exceedingly difficult to obtain water, thus causing the location to be abandoned as a community site. As a result, in the early 1840s the population shifted about 3 miles (5 km) to the south, where a settlement first formed by the Hope and Saxon families became known as "Pierceville". About this time, another community about 2 miles (3 km) northwest of Pierceville, named "Melendez", was formed.

On September 12, 1842, Seminole Indians attacked the McDaniel party near the community of Chocachatti, south of Brooksville, killing Charlotte (Mrs. Richard) Crum.

In 1850 a post office was established at Melendez. In 1854 it was replaced by a post office at Pierceville. Both towns were situated in the area that would become Brooksville.

In 1856 the county seat of Hernando County became the newly named town of Brooksville. The name was chosen to honor Preston Brooks, a congressman who had caned abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner nearly to death in 1856 on the floor of the Senate after Sumner gave an anti-slavery speech and disparaged Brooks' uncle, Senator Andrew Butler.[14] The Pierceville post office was renamed "Brooksville" in 1871.

Brooksville was settled by four families: the Howell family which settled the northern part of town; the Jon L. Mays family which settled the eastern part of town; the Hale family on the west; and the Parsons family on the south. The city was incorporated on October 13, 1880.

Slavery, lynchings and discrimination

A study of lynchings recorded in Hernando County in the late 19th and early 20th centuries revealed it had one of the highest per capita rates of violence against blacks in the United States.[15] In Brooksville, the county seat, several African-Americans were killed in the 1870s and 1920s. Arthur St. Clair, a community leader, was murdered in 1877 after he presided over an interracial marriage. After the murder, the investigation was stymied by local actions in defense of the white men accused in his killing.[16] In 1882, there was a brief uprising by blacks, three of whom were killed and many of whom were wounded by whites.[17] The 1920s saw a resurgence of Ku Klux Klan activity and lynchings; as a result, many black residents left the area.[18] Brooksville instituted a zoning law segregating neighborhoods in 1948.[15] Schools remained segregated until the late 1960s.[19]

One of the most notorious examples of racism in the city was the creation of the "Lewis Plantation and Turpentine Still", which claimed to show life in African-American rural communities, but in reality contained black residents dressing and acting in grotesque stereotypes as a means of entertaining white tourists.[20]

Depression Era

During the Great Depression, Brooksville suffered from a lack of currency. The school board paid teachers with chits, and Weeks Hardware "accepted chickens and sides of bacon" as payment.[21]

Recent times

Brooksville is a residential-commercial community. There are several modern medical facilities in the area including Bayfront Health Brooksville, Oak Hill Community Hospital, and Bayfront Health Spring Hill. A campus of Pasco–Hernando State College is a mile north of the city limits. The business section includes eleven shopping centers, and Brooksville–Tampa Bay Regional Airport is 6 miles (10 km) south of the city. There are three city parks with walking trails, sports, and picnicking facilities, including a nine-hole golf course and a library. The region also offers abundant hunting, fishing, biking, canoeing, kayaking and camping opportunities.

Jerome Brown, defensive tackle for the Philadelphia Eagles, graduated from Brooksville's Hernando High School, where he was often seen in the off season running laps around the track. In June 1988, he received praise for his calm demeanor as he helped disperse a group of Ku Klux Klan protesters in his hometown of Brooksville.[22] Brown died on June 25, 1992, at the age of 27, after he lost control of his ZR1 Chevrolet Corvette at high speed and crashed into a utility pole in Brooksville. Both he and his 12-year-old nephew, Gus, were killed in the accident. Brown was buried in Brooksville. In 2000, the Jerome Brown Community Center was opened in Brooksville in memory of Brown.[23]

A minor controversy arose in the summer of 2010 when local media and residents brought attention to the origin of the town's name, calling it "shameful".[24] The suggestion was made that the town should change its name in order to distance itself from its pro-slavery history. The idea was opposed by locals and not entertained by the city council. However, the city's official website did remove a page which discussed the Brooks/Sumner encounter and had cast Brooks in a positive light.

Public transportation

Media

- WWJB (1450 AM), radio station based in Brooksville

- The Hernando Times, an issue of the Tampa Bay Times, is published each Friday.

Notable people

- Tammy Alexander, murder victim known as "Caledonia Jane Doe", disappeared from Brooksville in 1979

- Bronson Arroyo, Major League Baseball pitcher; pitched for Hernando High School and graduated in 1995[26]

- Jerome Brown, defensive tackle for the Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League[27][28]

- John Capel, sprinter and professional football player

- Paul Farmer, co-founder of international social justice and health organization Partners In Health

- Wayne Garrett, Major League Baseball infielder, member of the 1969 Miracle Mets

- Mike Hampton, Major League Baseball player for the Houston Astros; born in Brooksville

- DuJuan Harris, former Central High (Brooksville) standout and current running back for the Jacksonville Jaguars

- William Sherman Jennings, governor of Florida 1901-1905

- George Lowe, television actor, grew up in Brooksville, worked for WWJB AM 1450, a local radio station

- Bill McCollum, U.S. congressman and Florida Attorney General; birthplace and childhood home

- Maulty Moore, former NFL defensive tackle for the Miami Dolphins, Cincinnati Bengals, and Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Tori Murden, the first woman to row solo across the Atlantic Ocean, and to ski to the geographic South Pole

- Jon Oliva, Savatage frontman and Trans-Siberian Orchestra composer[29]

- Taylor Rotunda, WWE wrestler, better known as Bo Dallas

- Windham Rotunda, WWE wrestler, better known as Bray Wyatt

- Stephen M. Sparkman, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Florida; born on a farm in Hernando County just south of Brooksville on July 29, 1849

- Hughie Thomasson, guitarist, songwriter, lead vocalist and leader of the Outlaws; lived in Brooksville

Cultural

- Canadian director Bob Clark's 1974 horror film Deathdream (aka Dead of Night; The Night Andy Came Home) was filmed entirely in Brooksville.[30]

References

- ↑ "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Sep 20, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Brooksville city, Florida". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

website = www

.ci .brooksville .fl .us - ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Canefight! Preston Brooks and Charles Sumner". Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ↑ Nancy E. Marion; Willard Oliver (22 July 2014). Killing Congress: Assassinations, Attempted Assassinations and Other Violence against Members of Congress. Lexington Books. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-0-7391-8360-1.

The assault on Sumner had such an impact on the sentiments that it is said to have intensified the animosity between the North and the South and was a major step in driving the country to Civil War.

- ↑ "Brooksville the home of the tangerine". University of South Florida. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Amidst controversy, Florida Blueberry Festival won't return to Brooksville". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ↑ "Peace Tree Trading Post".

- ↑ Brooksville Business Alliance - founders week slide show

- ↑ "The Compromise of 1850, The Kansas/Nebraska Act, Dred Scott, and John Brown's Raid". The University of Alabama. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- 1 2

- ↑ DeWitt, Dan (October 4, 2013). "Hernando's 100-year-old courthouse part of long, slow journey to justice". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ↑ Judge E. C. May of Inverness according to accounts by John W. Davis of Lecanto (July 3, 1955). "Negroes Tried 'To Take' Brooksville 70 Years Ago". Tampa Tribune. fivay.org. Retrieved April 26, 2017. . The event actually occurred in 1882.]

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "The Lewis Plantation". Florida Memory Blog. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ DeWitt, Dan (2003-12-24). "Hernando: A throwback that still thrives: Walking into Weeks Hardware, the oldest active business in town, is like going through a time warp to a business style that is rare today". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ↑ Scheiber, Dave (1988-08-29). "Cool Under Fire: WHEN THE KKK SHOWED UP IN HIS HOMETOWN, JEROME BROWN OF THE EAGLES PLAYED EXCELLENT DEFENSE". SI Vault - Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ↑ "Jerome Brown". City of Brooksville, Florida. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ↑ "Resident shines light on shameful old story behind Brooksville's name," St. Petersburg Times, July 25 2010

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-27. Retrieved 2013-11-26.

- ↑ http://www.tampabay.com/hometeam/blog/baseball-hernando-retire-bronson-arroyos-jersey/3790/

- ↑ http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/1992-06-26/sports/9202160584_1_eagles-defensive-line-palm-tree-dub-palmer

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-04-05. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Jon Oliva Biography on Savintage.com Archived August 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 1971 Ford Custom of the Brooksville Police Department (Internet Movie Cars Database)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brooksville, Florida. |