Bowerchalke

| Bowerchalke | |

|---|---|

Holy Trinity church, Bowerchalke | |

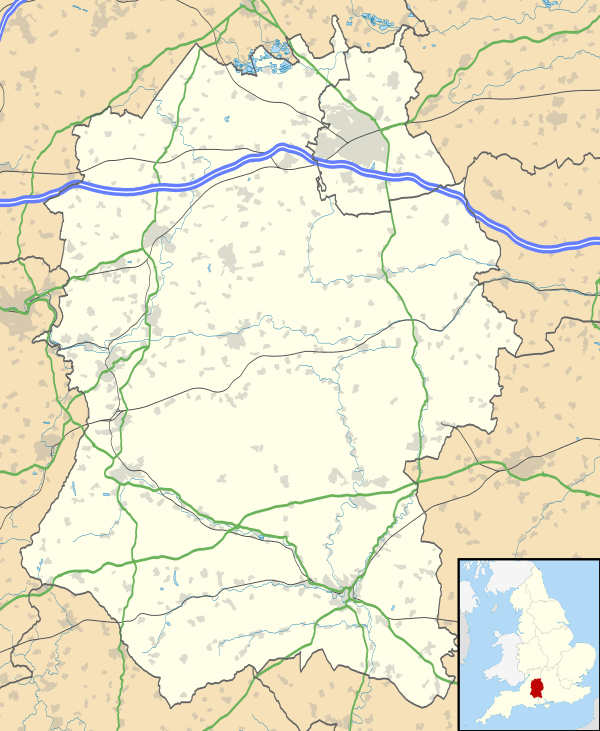

Bowerchalke Bowerchalke shown within Wiltshire | |

| Population | 379 (in 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU018228 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Salisbury |

| Postcode district | SP5 |

| Dialling code | 01722 |

| Police | Wiltshire |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| EU Parliament | South West England |

| UK Parliament | |

Bowerchalke is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about 9 miles (14 km) southwest of Salisbury. It is in the south of Wiltshire, about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the county boundary with Dorset and 2 miles (3.2 km) from that with Hampshire. The parish includes the hamlets of Mead End, Misselfore and Woodminton.

Bowerchalke is in the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, which is part of the Southern England Chalk Formation. The River Chalke, a classic chalk stream, rises in the village and joins the River Ebble at Broad Chalke, flowing into the Hampshire Avon south of Salisbury. The Bowerchalke Downs, also known as Woodminton Down, Marleycombe Down and Knowle Down, were defined as a 318 acres (129 ha) Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1971.

The Grade II* listed church of the Holy Trinity dates from the 13th century,[2][3] and Nobel Prize winning novelist William Golding is buried in the churchyard.

Origins

It is not known when Bowerchalke was first inhabited or what it was called but fragmentary records from Saxon times indicate that the whole Chalke Valley area was thriving, the River Ebble also being known as the River Chalke.[4]

The earliest signs

The earliest known sign of inhabitation is the bowl barrow on 'Marleycombe Down', which was probably built in either the Neolithic or the Bronze Age (3300–1200 BCE). The Bowerchalke Barrel Urn was excavated here in 1925 by Dr R Clay, and the repaired urn is part of the collection at the Wiltshire Museum, Devizes.[5]

4th century

Two hoards of gold and silver coins and rings from the 4th century were discovered by metal detectorists near Bowerchalke in the 20th and 21st centuries. They were used by the Durotriges, a Celtic tribe that lived in South Wiltshire and Dorset before the Roman occupation, became Romanised by c. 79 and gave their name to Dorset. The first discovery was a hoard of 17 gold staters (coins), examples of which are now displayed in the Salisbury Museum.[6] The second hoard of 2 gold rings and 5 silver coins dated to 380 was found in 2002 near the first.[7]

9th century

An Anglo-Saxon charter of 826 records the name of the area including Bowerchalke and Broad Chalke as Cealcan gemere.[8]

10th century

In 955 the Anglo-Saxon King Eadwig granted the nuns of Wilton Abbey an estate called Chalke which included land in Broad Chalke and Bowerchalke. The charter records the village name as aet Ceolcan.[8][9][10]

A charter in 974 records the name as Cheolca or Cheolcam.[8]

11th century

The Domesday Book in 1086 divided the Chalke Valley into eight manors, Chelke or Chelce or Celce (Bowerchalke and Broad Chalke), Eblesborne (Ebbesbourne Wake), Fifehide (Fifield), Cumbe (Coombe Bissett), Humitone (Homington), Odestoche (Odstock), Stradford (Stratford Tony and Bishopstone) and Trow (about Alvediston and Tollard Royal).[4]

12th century

In the 12th century the area was known primarily as the Stowford Hundred then subsequently as the Chalke Hundred. This included the parishes of Berwick St John, Ebbesbourne Wake, Fifield Bavant, Semley, Tollard Royal and 'Chalke'.[4] A charter of 1165 records the village name as Chalca, and the Pipe Rolls in 1174 record it as Chalche.[8]

13th century

The Curia Regis Rolls of 1207 records the village name as ChelkFeet of Fines, and another of 1242 records it as Chalke.[8] The name Burchelke first appeared in 1225.[4] The church of the Holy Trinity dates from the 13th century.

14th century

A Saxon charter of 1304 records the village name as Cheolc and Cheolcan. The Feudal Aids of 1316 uses Chawke, whilst a Saxon Cartulary of 1321 uses Cealce. The Tax lists of 1327, 1332 and 1377 variously record the name as Chalk Magna and Chalke Magna.[8] Brode Chalk was first mentioned in 1380.[4]

16th century

c. 1536 Henry VIII granted Chalke to William Herbert (later Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke) during the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[10] Henry VIII 'much valued' William Herbert, a successful and ambitious soldier, who also became his brother-in-law through his marriage to Anne Parr, sister of Henry's last wife Catherine Parr. King Henry heaped favours and honours (Knighthood) upon Herbert and granted the estates of Wilton, Remesbury (north Wiltshire), and Cardiff Castle.

19th century

Chalke was a comparatively large, disconnected estate that was separated into the two ecclesiastical parishes of Broad Chalk and Bowerchalke in 1880. Additionally, much of the land of the new Bowerchalke parish was annexed from Fifield Bavant in 1885.[4]

William Thick was born in 1845 at 'Misselfore Green' but left the village in 1868 to join the Metropolitan Police at Whitechapel in London (warrant No 49989). In 1889, while investigating the Whitechapel murders, Sergeant Thick was named in letters as a prospective perpetrator, to wit I have very good grounds to believe that the person who has committed the Whitechapel Murders is a member of the police force. ... Sergeant William Thick. (Sergeant Thick is no longer a suspect.)[11]

From 1878 until 1924 a unique village newspaper was written, printed, published and sold for a farthing by the Reverend Edward Collett, documenting the social history of the village. Two original sets of the papers still exist. One set is retained by Bodleian Library at Oxford and the second is on loan to the Wiltshire and Swindon Archive by its custodian Paul Lee, where it can be viewed in their offices at Chippenham. The papers were researched and published by Rex Sawyer as The Bowerchalke Parish Papers in 1989 after he had discovered the original printing press in his garden. In 2004 they were republished by The Hobnob Press as Collett's Farthing Newspaper: the Bowerchalke Village Newspaper, 1878-1924. ( ISBN 0-946418-22-5). Collett was also a keen amateur photographer and the majority of the photographs featured in the book are taken from his photograph album of that period.

20th century

Anglo-Canadian poet Marjorie Pickthall (1883–1922) lived in Bowerchalke from 1913 to 1919, spending summers at Chalke Cottage where she wrote prolifically. She also attempted to start an enterprise in market gardening as part of the war effort.[12]

In 1919 Reginald Herbert, 15th Earl of Pembroke started to sell the individual farms.[10]

First World War poet Siegfried Sassoon lived in the village for a while before moving to Heytesbury.

The Nobel Prize winning novelist William Golding, author of Lord of the Flies, The Inheritors, etc. is buried in the village churchyard, having lived the middle part of his life in a cottage on the banks of the River Chalke. He also named the Gaia hypothesis which was conceived by his fellow walking companion Dr James Lovelock who lived in the village from c. 1960-1980 at both 'Pixies Cottage' Misselfore and at 'Clovers Cottage' Mead End.

International violinist Iona Brown lived in the village at 'Misselfore Cottage' from 1968 until her death in 2004. She took part in an episode of BBC Radio 4's Kaleidoscope programme and explained how hard it was to play her signature piece The Lark Ascending by Ralph Vaughan Williams, she said that the lark song during long walks on nearby 'Marleycombe Down' was a central tenet of her performance.

Andy Barter photographer was born and lived at Woodminton farm, Bowerchalke 1967.

The village was the location for the fire in Stanley Kubrick's 1975 film Barry Lyndon based on William Makepeace Thackeray's novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon at 51°0′30.75″N 1°59′18.30″W / 51.0085417°N 1.9884167°W. The village school closed in 1976 and children from Bowerchalke now attend the school in neighbouring Broad Chalke. The old school buildings now serve as the Village Hall.

The village pub, The Bell Inn, closed in 1988 and is now a residential dwelling known as 'Bell House'.

The once renowned village cricket team, thanks in part to the dynasty of 'cricketing Gullivers' (Brian, David, Derek, Richard and Robin), closed c. 1973/74.

21st century

The village post office and general stores closed in 2003. The nearest post office is in Broad Chalke.

An article about the closures called Village of the Damned, written by David McKie, was published in The Guardian on 30 June 2005.[13] A response titled Bowerchalke is not the village of the Damned was written by Will Heaven, Assistant Comment Editor of the Daily Telegraph on 30 August 2009.[14]

In 2010 the Chalke Valley Cricket Club moved the cricket ground from the Chalke Valley Sports Centre in Broad Chalke to a new ground at Butt's Field, Bowerchalke, behind the Church under Marleycombe Hill, to allow a longer season and better facilities.

In 2011 Bowerchalke's new cricket ground became the main venue for the first Chalke Valley History Festival, organised by local author James Holland.[15]

Site of Special Scientific Interest

Marleycombe Down, Knowle Down and Woodminton Down are chalk grasslands which comprise the entire southern outlook of the village. They are jointly known as the Bowerchalke Downs, a Site of Special Scientific Interest with many species of plants, insects and butterflies.

Geology

The rocks of Bowerchalke that can be seen today were deposited underwater between 120 and 70 million years ago (mya) until they were then uplifted from the sea and have been sculpted by periglacial weathering and erosion over the last 1 million years.

The unseen underlying rocks of Bowerchalke started to form in shallow seas surrounding volcanic islands up to 1,000 million years ago (Proterozoic), about 60-70 degrees south of the equator, the latitude of present-day Argentina. 'Proto-Bowerchalke' and the rest of England and Wales are part of Avalonia, a micro-continent that broke away from the southern landmass, and was 50 degrees south of the equator about 500 mya. It joined with Baltica just south of the equator 400 mya, and was crushed between Baltica, and Laurasia (North America), and Gondwanaland (Africa, Australia, Antarctica and South America) 350 mya whilst near the equator (Variscan orogeny). Avalonia was landlocked and buffeted within Pangaea just north of the equator 270 mya, and became part of a desert in the northern tropics 230 mya. Eventually it formed the west coast of Eurasia as America split away to form the Atlantic Ocean 120 mya. Bowerchalke then laid under warm chalk forming seas until being uplifted 70 mya as Africa started to collide with the European plate in the (Alpine Orogeny), and in the cooler shallow water river clay sediments capped the chalk. In the last million years the periglacial weathering has completely removed several hundred feet of chalk.

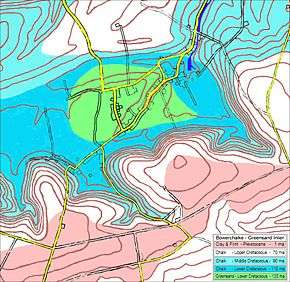

The main portion of the village is formed on the unique 'Bowerchalke greensand inlier' (an area of older rock completely surrounded by younger layers), highlighted in green on the adjacent map. It is not immediately obvious to the naked eye or on the standard Ordnance Survey maps with 10 metre contours[16] but the apex is strikingly characterised by the 'island' drawn on the Andrews 1773 map. Its presence can be detected in the friable sandy soils in the centre of the village.

The Greensand inlier is a dome shaped area of hard, coarse, olive-green coloured sandstone rock which has had its covering of softer chalk eroded away by 60 million years of weathering since the region was lifted out of the sea. The Cretaceous Upper Greensand is about 120 million years old and was deposited in brackish, oxygen depleted, water when Bowerchalke was located at around 35 degrees north of the equator, roughly equivalent to southern Spain and Portugal. At that time it was still part of the supercontinent Pangea which was just starting to split and form the Atlantic Ocean. The nearest continuous Upper Greensand exposure is along the A30 in the Nadder valley at Fovant. The closest 'unique greensand inlier' is near Andover in Hampshire.

Surrounding the greensand is a ring of younger Lower Cretaceous Chalk which is about 100 million years old (darker blue on the adjacent map). The chalk was formed in warm, shallow, well oxygenated waters from the remains of micro-organisms (coccolithophores), over millions of years. At this time the Atlantic Ocean was about 100 miles wide and Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Somerset were a single island with rivers draining their nutrients into the warm sea that covered Wiltshire, Hampshire, the east of England, Northern France, Denmark and northern Germany.

Surrounding the lower chalk is a ringlike region of still younger Middle Cretaceous chalk (about 80 my)(light blue on the adjacent map). The whole area is bounded by the 'vast expanse' of Upper Cretaceous chalk (shown white on the adjacent map) that continued to form when Bowerchalke was about 45 degrees north, roughly equivalent to Bordeaux or the Dordogne in France. It was still under a shallow sea but Somerset, Ireland and Scotland had become separate islands. Bowerchalke was probably 15–30 miles offshore from the 'coast' between Shaftesbury and Dorchester.

Above the exposed Cretaceous chalk slopes of Marleycombe the hilltops are covered with a very young layer of Pleistocene 'clay with flint' that is about 1-10 million years old and formed by alluvial sediments in cold shallow waters (pink on the adjacent map). The flints were formed in multiple layers as the clay sediment built up, and were then concentrated into a single dense layer as the last million years of sub glacial weathering washed the minute clay particles away.

The steepness of the north facing Marleycombe Down contrasts with the gentle rolling slopes towards Ebbesbourne Wake. This is mainly due to erosion during the sustained permafrost and tundra like conditions in the periglacial zones of multiple ice ages. Although the southern limit of the main glaciation is a line across North Wiltshire that corresponds to the M4 corridor, the sun rarely melted the north facing snow pockets on Marlecombe Down, thus they eroded the soft chalks and clays by eating back into them, leaving the very steep scarp faces. The sporadic melting of snow and ice was forced to drain north east along the course of the River Chalke and River Ebble in occasional summers, plus scouring the now dry channel that forms Church Street and Costers Lane. The southern boundary between the greensand and chalk, is concealed beneath a layer of heavy clay that has accumulated at the bottom Marleycombe Down due to the periglacial solifluction. This scouring has also located the natural spring that supplies the River Chalke, whereby the rainfall from the surrounding watershed, having been filtered and channeled through the porous chalk, rises at the natural spring at 'Mead End' where the water table sits on the underlying impervious greensand layer.

References

- ↑ "Wiltshire Community History - Census". Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Church of Holy Trinity, Bower Chalke (1198318)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bowerchalke - Holy Trinity". Chalke Valley Church. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ebbesbourne Wake through the Ages by Peter Meers

- ↑ "Bowerchalke Barrel Urn". Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ "Gold Coins". The Salisbury Museum. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bowerchalke Hoard is declared treasure". thisiswiltshire.co.uk. 10 October 2002. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Broad Chalke, A History of a South Wiltshire Village, its Land & People Over 2,000 years. By 'The People of the Village', 1999

- ↑ British History Online (.ac.uk) Broad Chalke

- 1 2 3 "Broad Chalke". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ Moody, Frogg. "Sergeant William Thick". Casebook: Jack the Ripper. Thomas Schachner. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ Godard, Barbara. "Pickthall, Marjorie Lowry Christie". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ McKie, David (30 June 2005). "Village of the damned". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ Heaven, Will (30 August 2009). "Bowerchalke is not 'the village of the damned'". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ Chalke Valley History Festival

- ↑ www.streetmap.co.uk Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bowerchalke. |

- Bowerchalke at the BBC Domesday Project

- Images of Bowerchalke at Geograph.com

- The Durotriges at Romans in Britain

- Cranborne Chase - Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

- Cranborne Chase AoONB - Geology map showing Bowerchalke inlier

- Bowerchalke church tower at the Salisbury Diocesan Guild of Bell Ringers

- Bowerchalke at Wiltshire Community History

- Wiltshire Community History copy of Andrews' and Dury's map - 1773

- Wiltshire Community History copy of Andrews' and Dury's map - 1810