Boris Karloff

| Boris Karloff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

William Henry Pratt 23 November 1887 Camberwell, Surrey, England |

| Died |

2 February 1969 (aged 81) Midhurst, Sussex, England |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1909–1969 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Sara Karloff (daughter), with Dorothy Stine[1] |

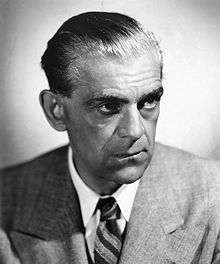

William Henry Pratt (23 November 1887 – 2 February 1969), better known by his stage name Boris Karloff (/ˈkɑːrlɒf/), was an English actor who was primarily known for his roles in horror films.[2] He portrayed Frankenstein's monster in Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Son of Frankenstein (1939). He also appeared as Imhotep in The Mummy (1932).

In non-horror roles, he is best-known for narrating and as the voice of Grinch in the animated television special of Dr. Seuss' How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966). For his contribution to film and television, Boris Karloff was awarded two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Early years

Boris Karloff was born William Henry Pratt on 23 November 1887,[3] at 36 Forest Hill Road, Camberwell, Surrey (now London), England,[4] but Pratt stated that he was born in nearby Dulwich.[5] His parents were Edward John Pratt, Jr. and Eliza Sarah Millard. His brother, Sir John Thomas Pratt, was a British diplomat.[6] His mother's maternal aunt was Anna Leonowens, whose tales about life in the royal court of Siam (now Thailand) were the basis of the musical The King and I. Pratt was bow-legged, had a lisp, and stuttered as a young boy.[7] He conquered his stutter, but not his lisp, which was noticeable throughout his career in the film industry.

Pratt spent his childhood years in Enfield, in the County of Middlesex. He was the youngest of nine children, and following his mother's death was brought up by his elder siblings. He received his early education at Enfield Grammar School, and later at the private schools of Uppingham School and Merchant Taylors' School. After this, he attended King's College London where he took studies aimed at a career with the British Government's Consular Service. However, in 1909, he left university without graduating and drifted, departing England for Canada, where he worked as a farm labourer and did various odd itinerant jobs until happening upon acting.[8]

Acting career

Pratt began appearing in theatrical performances in Canada, and during this period he chose Boris Karloff as his stage name. Some have theorised that he took the stage name from a mad scientist character in the novel The Drums of Jeopardy called "Boris Karlov". However, the novel was not published until 1920, at least eight years after Karloff had been using the name on stage and in silent films (Warner Oland played "Boris Karlov" in a film version in 1931). Another possible influence was thought to be a character in the Edgar Rice Burroughs fantasy novel H. R. H. The Rider which features a "Prince Boris of Karlova", but as the novel was not published until 1915, the influence may be backward, that Burroughs saw Karloff in a play and adapted the name for the character. Karloff always claimed he chose the first name "Boris" because it sounded foreign and exotic, and that "Karloff" was a family name (from Karlov—in Cyrillic, Карлов—a name found in several Slavic countries, including Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria[9]). However, his daughter Sara Karloff publicly denied any knowledge of Slavic forebears, "Karloff" or otherwise. One reason for the name change was to prevent embarrassment to his family. Whether or not his brothers (all dignified members of the British Foreign Service) actually considered young William the "black sheep of the family" for having become an actor, Karloff apparently worried they felt that way. He did not reunite with his family until he returned to Britain to make The Ghoul (1933), extremely worried that his siblings would disapprove of his new, macabre claim to world fame. Instead, his brothers jostled for position around him and happily posed for publicity photographs. After the photo was taken, Karloff’s brothers immediately started asking about getting a copy of their own. The story of the photo became one of Karloff’s favorites.[10]

Karloff joined the Jeanne Russell Company in 1911 and performed in towns like Kamloops (British Columbia) and Prince Albert (Saskatchewan). After the devastating tornado in Regina on 30 June 1912, Karloff and other performers helped with clean-up efforts.[11] He later took a job as a railway baggage handler and joined the Harry St. Clair Co. that performed in Minot, North Dakota, for a year in an opera house above a hardware store.

Whilst he was trying to establish his acting career, Karloff had to perform years of manual labour in Canada and the U.S. in order to make ends meet. He was left with back problems from which he suffered for the rest of his life. Because of his health, he did not enlist in World War I.

During this period, Karloff worked in various theatrical stock companies across the U.S. to hone his acting skills. Some acting companies mentioned were the Harry St. Clair Players and the Billie Bennett Touring Company. By early 1918 he was working with the Maud Amber Players in Vallejo, California, but because of the Spanish Flu outbreak in the San Francisco area and the fear of infection, the troupe was disbanded. He was able to find work with the Haggerty Repertory for a while, (according to the 1973 obituary of Joseph Paul Haggerty, he and Boris Karloff remained lifelong friends). According to Karloff, in his first film he appeared as an extra in a crowd scene for a Frank Borzage picture at Universal for which he received $5; the title of this film has never been traced.[12]

Hollywood

.jpg)

Once Karloff arrived in Hollywood, he made dozens of silent films, but this work was sporadic, and he often had to take up manual labour such as digging ditches or delivering construction plaster to earn a living. Some of his early roles were in film serials, such as The Masked Rider (1919), in Chapter 2 of which he can be glimpsed onscreen for the first time, The Hope Diamond Mystery (1920) and King of the Wild (1930). In these early roles, he was often cast as an exotic Arabian or Indian villain. A key film which brought Karloff recognition was The Criminal Code (1931), a prison drama directed by Howard Hawks in which he reprised a dramatic part he had played on stage. Another significant role in the autumn of 1931 saw Karloff play a key supporting part as an unethical newspaper reporter in Five Star Final, a film about tabloid journalism which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. Before appearing in horror films, Karloff had a small role as a mob boss in Hawks' gangster film Scarface, which was not released until 1932 because of censorship issues.

Stardom in the 1930s

Karloff acted in eighty movies before being found by James Whale and cast in his eighty-first movie, Frankenstein. Karloff's role as Frankenstein's monster in Frankenstein propelled him to stardom. The bulky costume with four-inch platform boots made it an arduous role but the costume and extensive makeup produced the classic image. The costume was a job in itself for Karloff with the shoes weighing 11 pounds (5.0 kg) each.[13] Universal Studios was quick to acquire ownership of the copyright to the makeup format for the Frankenstein monster that Jack P. Pierce had designed. Karloff was soon cast as Imhotep who is revived in The Mummy, a mute butler in The Old Dark House (with Charles Laughton) and the starring role in The Mask of Fu Manchu, which were all released within a few months of each other in late 1932. These films confirmed Karloff's new-found stardom. The 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m) brown-eyed Karloff still played roles in other genres besides horror, such as a religious First World War soldier in the John Ford epic The Lost Patrol (1934).

Horror, however, had now become Karloff's primary genre, and he gave a string of lauded performances in Universal's horror films, including several with Bela Lugosi, his main rival as heir to Lon Chaney's status as the leading horror film star. While the long-standing, creative partnership between Karloff and Lugosi never led to a close friendship, it produced some of the actors' most revered and enduring productions, beginning with The Black Cat (1934) and continuing with Gift of Gab (1934), The Raven (1935) and The Invisible Ray (1936). Karloff reprised the role of Frankenstein's monster in two further films, Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Son of Frankenstein (1939), the latter also featuring Lugosi, with Basil Rathbone replacing Colin Clive as the scientist playing god. Rathbone appeared with Karloff again in Tower of London (1939) as the murderous henchman of King Richard III. Karloff revisited the Frankenstein mythos in several later films as well, taking the starring role of the villainous Dr. Niemann in House of Frankenstein (1944), in which the monster was played by Glenn Strange. He reprised the role of the "mad scientist" in 1958's Frankenstein 1970 as Baron Victor von Frankenstein II, the grandson of the original creator. The finale reveals that the crippled Baron has given his own face (i.e., Karloff's) to the monster.

_still_1.jpg)

Between 1938 and 1940, Karloff appeared in five films for Monogram Pictures. Directed by William Nigh, Karloff portrayed character James Lee Wong, a Chinese detective. More commonly referred to as Mr. Wong, Karloff's portrayal of the character is an example of Hollywood's use of yellowface and its portrayal of East Asians in the earlier half of the 20th century.

Karloff appeared at a celebrity baseball game as Frankenstein's monster in 1940, hitting a gag home run and making catcher Buster Keaton fall into an acrobatic dead faint as the monster stomped into home plate. Meanwhile, Karloff appeared in British Intelligence (1940) with Margaret Lindsay for Warners.

The 1940s and 1950s

_1.jpg)

An enthusiastic performer, he returned to the Broadway stage in the original production of Arsenic and Old Lace in 1941, in which he played a homicidal gangster enraged to be frequently mistaken for Karloff. Frank Capra cast Raymond Massey in the 1944 film, which was shot in 1941, while Karloff was still appearing in the role on Broadway (the play’s producers allowed the film to be made under the condition that it not be released until the play closed). He reprised the role on television in the anthology series The Best of Broadway (1955), and with Tony Randall and Tom Bosley in a 1962 production on the Hallmark Hall of Fame. In 1944, he underwent a spinal operation to relieve his chronic arthritic condition.[14]

Meanwhile, his connection with Bela Lugosi continued with Black Friday (1940), You'll Find Out (also 1940) and The Body Snatcher (1945), the first of three films in a contract with RKO produced by Val Lewton. Isle of the Dead (also 1945) and Bedlam (1946) completed the trio.

In a 1946 interview with Louis Berg of the Los Angeles Times, Karloff discussed his arrangement with RKO, working with Lewton and his reasons for leaving Universal. Karloff left Universal because he thought the Frankenstein franchise had run its course. Berg wrote that the last installment in which Karloff appeared—House of Frankenstein—was what he called a "'monster clambake,' with everything thrown in—Frankenstein, Dracula, a hunchback and a 'man-beast' that howled in the night. It was too much. Karloff thought it was ridiculous and said so". Berg explained that the actor had "great love and respect for" Lewton, who was "the man who rescued him from the living dead and restored, so to speak, his soul."[15] For the Danny Kaye comedy, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947), Karloff appeared in a brief but starring role as Dr. Hugo Hollingshead, a psychiatrist. Director Norman Z. McLeod shot a sequence with Karloff in the Frankenstein monster make-up, but it was deleted from the finished film.

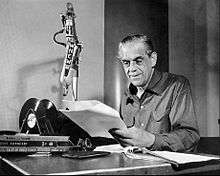

During this period, Karloff was also a frequent guest on radio programmes, whether it was starring in Arch Oboler's Chicago-based Lights Out productions (including the episode "Cat Wife") or spoofing his horror image with Fred Allen or Jack Benny. In 1949, he was the host and star of Starring Boris Karloff, a radio and television anthology series for the ABC broadcasting network.

He also appeared as the villainous Captain Hook in the play Peter Pan with Jean Arthur. He was nominated for a Tony Award for his work opposite Julie Harris in The Lark, by the French playwright Jean Anouilh, about Joan of Arc, which was reprised on Hallmark Hall of Fame.

During the 1950s, he appeared on British television in the series Colonel March of Scotland Yard, in which he portrayed John Dickson Carr's fictional detective Colonel March, who was known for solving apparently impossible crimes. Christopher Lee appeared alongside Karloff in the episode "At Night, All Cats are Grey" broadcast in 1955.[16] A little later, Karloff co-starred with Lee in the film Corridors of Blood (1958).

Karloff, along with H. V. Kaltenborn, was a regular panelist on the NBC game show, Who Said That? which aired between 1948 and 1955. Later, as a guest on NBC's The Gisele MacKenzie Show, Karloff sang "Those Were the Good Old Days" from Damn Yankees while Gisele MacKenzie performed the solo, "Give Me the Simple Life". On The Red Skelton Show, Karloff guest starred along with horror actor Vincent Price in a parody of Frankenstein, with Red Skelton as "Klem Kadiddle Monster"', and introductions for The Veil (1958) but these was never actually broadcast, and only came to light in the 1990s.

Last years

Karloff donned the monster make-up for the last time in 1962 for a Halloween episode of the TV series Route 66, which also featured Peter Lorre and Lon Chaney, Jr.[17] During this period, he hosted and acted in a number of television series, including Thriller and Out Of This World. In the 1960s, Karloff appeared in several films for American International Pictures, including The Comedy of Terrors, The Raven and The Terror (all 1963), the latter two directed by Roger Corman.

In 1966, Karloff also appeared with Robert Vaughn and Stefanie Powers in the spy series The Girl from U.N.C.L.E., in the episode "The Mother Muffin Affair," Karloff performed in drag as the titular character. That same year, he also played an Indian Maharajah on the installment of the adventure series The Wild Wild West titled "The Night of the Golden Cobra". In 1967, he played an eccentric Spanish professor who believes himself to be Don Quixote in a whimsical episode of I Spy titled "Mainly on the Plains".

In the mid-1960s, he enjoyed a late-career surge in the United States when he narrated the made-for-television animated film of Dr. Seuss' How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and also provided the voice of the Grinch, although the song "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch" was sung by the American voice actor Thurl Ravenscroft. The film was first broadcast on CBS-TV in 1966. Karloff later received a Grammy Award for "Best Recording For Children" after the recording was commercially released.[18] Because Ravenscroft (who never met Karloff in the course of their work on the show)[19] was uncredited for his contribution to How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, his performance of the song was often mistakenly attributed to him. Meanwhile back in Great Britain, he was cast in Die, Monster, Die! (a.k.a. Monster of Terror, 1965). British actress Suzan Farmer, who played his daughter in the film, later recalled Karloff was aloof during production "and wasn’t the charming personality people perceived him to be".[20] Around the same time, he also starred in the second feature film of the British director Michael Reeves,The Sorcerers (1966).

Karloff starred in Targets (1968), a film directed by Peter Bogdanovich, featuring two separate stories that converge into one. In one, a disturbed young man kills his family, then embarks on a killing spree. In the other, a famous horror-film actor contemplates then confirms his retirement, agreeing to one last appearance at a drive-in cinema. Karloff starred as the retired horror film actor, Byron Orlok, a thinly disguised version of himself; Orlok was facing an end of life crisis, which he resolved through a confrontation with the gunman at the drive-in cinema.

Around the same time, he played occult expert Professor Marsh in a British production titled The Crimson Cult (Curse of the Crimson Altar, also 1968), which was the last Karloff film to be released during his lifetime.

He ended his career by appearing in four low-budget Mexican horror films: Isle of the Snake People, The Incredible Invasion, Fear Chamber and House of Evil. This was a package deal with Mexican producer Luis Enrique Vergara. Karloff's scenes were directed by Jack Hill and shot back-to-back in Los Angeles in the spring of 1968. The films were then completed in Mexico. All four were released posthumously, with the last, The Incredible Invasion, not released until 1971, two years after Karloff's death. Cauldron of Blood, shot in Spain in 1967 and co-starring Viveca Lindfors, was also released after Karloff's death.

While shooting his final films, Karloff suffered from emphysema. Only half of one lung was still functioning and he required oxygen between takes.

Spoken word recordings and horror anthologies

He recorded the title role of Shakespeare's Cymbeline for the Shakespeare Recording Society (Caedmon Audio). The recording was originally released in 1962. A download of his performance is available from audible.com. He also recorded the narration for Sergei Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf with the Vienna State Opera Orchestra under Mario Rossi.

Records he made for the children's market included Three Little Pigs and Other Fairy Stories, Tales of the Frightened (volume 1 and 2), Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories and, with Cyril Ritchard and Celeste Holm, Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes,[21] and Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark.[22]

Karloff was credited for editing several horror anthologies, commencing with Tales of Terror (Cleveland and NY: World Publishing Co, 1943) (compiled with the help of Edmond Speare).[23] This wartime-published anthology went through at least five printings to September 1945. It has been reprinted recently (Orange NJ: Idea Men, 2007). Karloff's name was also attached to And the Darkness Falls (Cleveland and NY: World Publishing Co, 1946); and The Boris Karloff Horror Anthology (London: Souvenir Press, 1965; simultaneous publication in Canada - Toronto: The Ryerson Press; US pbk reprint NY: Avon Books, 1965 retitled as Boris Karloff's Favourite Horror Stories; UK pbk reprints London: Corgi, 1969 and London: Everest, 1975, both under the original title), though it is less clear whether Karloff himself actually edited these.

Tales of the Frightened (Belmont Books, 1963), though based on the recordings by Karloff of the same title, and featuring his image on the book cover, contained stories written by Michael Avallone; the second volume, More Tales of the Frightened, contained stories authored by Robert Lory. Both Avallone and Lory worked closely with Canadian editor and book packager Lyle Kenyon Engel, who also ghost-edited a horror story anthology for horror film star Basil Rathbone.

Personal life

Beginning in 1940, Karloff dressed as Father Christmas every Christmas to hand out presents to physically disabled children in a Baltimore hospital.[24] He never legally changed his name to "Boris Karloff." He signed official documents "William H. Pratt, a.k.a. Boris Karloff."[25]

He was a charter member of the Screen Actors Guild, and he was especially outspoken due to the long hours he spent in makeup while playing Frankenstein's Monster. [26]

He married five times and had one child, daughter Sara Karloff, by his fourth wife. One marriage was in 1946 right after his divorce.[27][28] At the time of his daughter's birth, he was filming Son of Frankenstein and reportedly rushed from the film set to the hospital while still in full makeup.[29]

Death

He spent his retirement in England at his country cottage named Roundabout in the Hampshire village of Bramshott. A longtime heavy smoker, he had emphysema which left him with only half of one lung still functioning.[30] He contracted bronchitis in 1968 and was hospitalised at University College Hospital.[31][32] He died of pneumonia at the King Edward VII Hospital, Midhurst, in Sussex, on 2 February 1969, at the age of 81.[33][3]

His body was cremated following a requested modest service at Guildford Crematorium, Godalming, Surrey, where he is commemorated by a plaque in the Garden of Remembrance. A memorial service was held at St Paul's, Covent Garden (the Actors' Church), London, where there is also a plaque.

During the run of Thriller, Karloff lent his name and likeness to a comic book for Gold Key Comics based upon the series. After Thriller was cancelled, the comic was retitled Boris Karloff's Tales of Mystery. An illustrated likeness of Karloff continued to introduce each issue of this publication for nearly a decade after his death; the comic lasted until the early 1980s. In 2009, Dark Horse Comics began publishing reprints of Boris Karloff's Tales of Mystery in a hard-bound edition.

Legacy

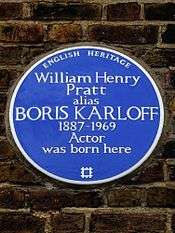

For his contribution to film and television, Boris Karloff was awarded two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, at 1737 Vine Street for motion pictures, and 6664 Hollywood Boulevard for television.[34] Karloff was featured by the U.S. Postal Service as Frankenstein's Monster and the Mummy in its series "Classic Monster Movie Stamps" issued in September 1997.[35] In 1998, an English Heritage blue plaque was unveiled in his hometown in London. The British film magazine Empire in 2016 ranked Karloff's portrayal as Frankenstein's monster the sixth-greatest horror movie character of all time.[36]

Filmography

Radio appearances

| Program | Episode | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lights Out | The Dream | March 23, 1938 | [37] |

| Lights Out | Valse Triste | March 30, 1938 | [38] |

| Lights Out | The Cat Wife | April 6, 1938 | [39] |

| Lights Out | Three Matches | April 13, 1938 | [40] |

| Lights Out | Night On The Mountain | April 20, 1938 | [41] |

| Screen Guild Players | Arsenic and Old Lace | November 25, 1946 | [42] |

| Lights Out | Death Robbery | July 16, 1947 | [43] |

| Lights Out | The Ring | July 30, 1947 | [44] |

| Philip Morris Playhouse | Journey to Nowhere | February 10, 1952 | [45] |

| Theatre Guild on the Air | "The Sea Wolf" | April 27, 1952 | [46] |

| Musical Comedy Theater | Yolanda and the Thief | November 26, 1952 | [47] |

See also

- Grammy Award for Best Album for Children

- Karloff, 2014 one-man play by Randy Bowser.[48]

References

- ↑ "The Monster's Daughter". SFGate. 2006-05-28. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ↑ Obituary Variety, 5 February 1969, page 71.

- 1 2 Biography Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ A commemorative plaque can be seen today on the property marking it as the place of his birth

- ↑ This Is Your Life TV Show (2:46)

- ↑ Jacobs, Stephen (Spring 2007). "Karloff in Saskatchewan". Saskatchewan History. 59 (1). ISSN 0036-4908. OCLC 2443952.

- ↑ Nollen, Scott A.; Sara Jane Karloff (1999). Boris Karloff: A Gentleman's Life. Baltimore: Midnight Marquee Press. p. 18. ISBN 1-887664-23-8.

- ↑ "Boris Karloff". This Is Your Life. Season 6. 20 November 1957. NBC. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ "Karlov Surname Distribution". forebears.co.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2015

- ↑ Mank, Gregory William (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff : the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. p. 140. ISBN 0786434805.

- ↑ Waiser, William A. (2005). Saskatchewan: A New History. Calgary: Fifth House. ISBN 1-894856-43-0.

- ↑ Beverley Bare Buehrer. 'Boris Karloff: A Bio-bibliography'. Greenwood Press: Westport, Connecticut (1993), pages 5–6.

- ↑ Buehrer, Beverley B. (1993). Boris Karloff: A bio-bibliography. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. p. 88. ISBN 031327715X

- ↑ "Karloff Undergoes Operation". The New York Times. July 25, 1944.

- ↑ Louis Berg (12 May 1946). "Farewell to Monsters" (PDF). The Los Angeles Times. p. F12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ↑ Johnson, Tom (2009). The Christopher Lee Filmography: All Theatrical Releases, 1948–2003. p. 79. McFarland.

- ↑ Buehrer, Beverley Bare (1993). Boris Karloff: A Bio-bibliography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 137. ISBN 978-0313277153.

- ↑ "Past Winners Search for "grinch"". Grammy.com. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "He’s Grrrrreat! The Thurl Ravenscroft Interview," Hogan's Alley No. 14, 1998

- ↑ "Suzan Farmer, stalwart of Hammer films – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ↑ Deborah Stead (11 June 1989). "Children's Books; Play me a Story: it's tape time". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ↑ The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll, read by Boris Karloff, Saland Publishing / IODA, 2008

- ↑ Mike Ashley and William G. Contento (eds) The Supernatural Index: A Listing of Fantasy, Supernatural, Occult, Weird and Horror Anthologies. Westport CT and London: Greenwood Press, 1995, p. 26.

- ↑ "Boris Karloff". Current Biography: 454–56. 1941. ISSN 0011-3344.

- ↑ "Matinee Classics - Boris Karloff Biography & Filmography". Archived from the original on 2014-07-19.

- ↑ "Five Things You Might Not Have Known About Boris Karloff" (Web). BBC America. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ↑ "Boris Karloff Gets a Divorce". The New York Times. April 10, 1946.

- ↑ "Boris Karloff Marries". The New York Times. April 12, 1946.

- ↑ "Split Screen: The men behind the masks". Yahoo! Movies. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Buehrer, Beverley Bare Boris Karloff: A Bio-Bibliography (1993) p. 18

- ↑ "Boris Karloff in Hospital". The New York Times. February 20, 1968.

- ↑ "Karloff Out of Hospital". The New York Times. United Press International. February 25, 1968.

- ↑ "Role Changed His Life. Boris Karloff, Master Horror-Film Actor, Dies". The New York Times. February 4, 1969.

- ↑ Lindsay, Cynthia (1995). Dear Boris. New York: Proscenium Publishers. ISBN 0-87910-076-1.

- ↑ "Classic Monster Movie Stamps". United States Postal Service. 12 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ↑ "The 100 best horror movie characters". Empire. 18 October 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ↑ Boris Karloff, Best of the Bogeymen, To Appear on 'Lights Out' Show - Let's all sit down and have a good scare., North Towanda News, 23 March 1938, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ 11:30 p.m.--Lights Out (WIBA, WMAQ): "Valse Triste," with Boris Karloff., Wisconsin State Journal, 30 March 1938, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ 11:30 p.m.--Lights Out (WIBA, WMAQ): Boris Karloff in "Cat Wife.", Wisconsin State Journal, 6 April 1938, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ 11:30 p.m.--Lights Out (WIBA, WMAQ): "Three Matches" with Boris Karloff, Wisconsin State Journal, 13 April 1938, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ 11:30 p.m.--Lights Out (WIBA, WMAQ): Boris Karloff in "Night on the Mountain.", Wisconsin State Journal, 20 April 1938, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ "Boris Karloff to Repeat 'Arsenic' Role Monday, WHP". Harrisburg Telegraph. November 23, 1946. p. 19. Retrieved September 13, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ 8:30 p.m.--Lights Out (WENR): returns to the air with Boris Karloff., Wisconsin State Journal, 16 July 1947, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ 8:30 p.m.--Lights Out (WENR): Boris Karloff and a disappearing hand., Wisconsin State Journal, 30 July 1947, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Digital Deli Too

- ↑ Kirby, Walter (February 10, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 38. Retrieved June 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Kirby, Walter (April 27, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 48. Retrieved May 8, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Kirby, Walter (November 23, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 48. Retrieved June 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Wright, Carlee (11 November 2014). "One-man play tells of man behind Frankenstein's monster". Statesman Journal. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boris Karloff. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Boris Karloff |

- Boris Karloff at the Internet Broadway Database

- Boris Karloff on IMDb

- Official site

- Karloff's birthplace

- Vertlieb's Views: Boris Karloff

- Literature on Boris Karloff

- Lights Out: Cat Wife (NBC, 6 April 1938)—Karloff's performance in the radio horror classic