Scarface (1932 film)

| Scarface | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Scarface by Armitage Trail |

| Starring | |

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | Edward Curtiss |

Production company |

The Caddo Company |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Box office | $600,000[2] |

Scarface (also known as Scarface: The Shame of the Nation and The Shame of a Nation) is a 1932 American pre-Code gangster film starring Paul Muni as a gangster named Antonio "Tony" Camonte. It was produced by Howard Hughes and Howard Hawks. As well as producing, Hawks also directed the film. Written by Ben Hecht, the screenplay is based on Armitage Trail's 1929 novel of the same title, which is loosely depicts the rise and fall of Al Capone. The film features Ann Dvorak as Camonte's sister, and also stars Karen Morley, Osgood Perkins, George Raft, and Boris Karloff. The plot centers on Camonte, who aggressively and violently moves up the ranks in the Chicago gangland world. A version of the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre is represented in a scene from the film.

Believing that the film was too violent and that it glorified the illegal acts of the gangster, Hollywood censorship offices called for major alterations of the film, including an alternate ending that would more clearly condemn and shame Tony Camonte. The secondary title of the film—Scarface: The Shame of a Nation—and a prologue condemning gangster crimes were both added by request of the censorship offices. Due to the censors, the film was released a year late; however, some showings retained the original, violent ending. Audience reception was positive, but censors banned the film in several cities and states, forcing Howard Hughes to remove the film from circulation and store it in his vault. The rights to the film were recovered after the death of Hughes in the 1970s. Along with Little Caesar and The Public Enemy (both 1931), Scarface is regarded as among the most significant gangster films, and it greatly influenced the future of the genre.

Scarface was added to the National Film Registry in 1994 by the Library of Congress. In 2008, the American Film Institute listed Scarface as the sixth best film in the gangster film genre in its "Ten Top Ten". The film was the basis for the Brian De Palma 1983 film of the same name starring Al Pacino.

Plot

In 1920s Chicago, Italian immigrant Antonio "Tony" Camonte acts on the orders of Italian mafioso John "Johnny" Lovo and kills "Big" Louis Costillo, the leading crime boss of the city's South Side. Johnny then takes control of the South Side with Tony as his key lieutenant, selling large amounts of illegal beer to speakeasies and muscling in on bars run by rival outfits. However, Johnny repeatedly warns Tony not to mess with the Irish gangs led by O'Hara, who runs the North Side. Tony soon starts ignoring these orders, shooting up bars belonging to O'Hara, and attracting the attention of the police and rival gangsters. Johnny realizes that Tony is out of control and has ambitions to take his position.

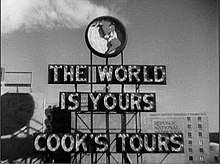

Meanwhile, Tony pursues Johnny's girlfriend Poppy with increasing confidence. At first, she is dismissive of him but pays him more attention as his reputation rises. At one point, she visits his "gaudy" apartment where he shows her his view of an electric billboard advertising Cook's Tours, which features the slogan that has inspired him: "The World is Yours."

Tony eventually decides to declare war and take over the North Side. He sends the coin flipping Guino Rinaldo, one of his best men and close friend, to kill O'Hara in a florist's shop that he uses as his base. This brings heavy retaliation from the North Side gangs, now led by Gaffney and armed with Thompson submachine guns—a weapon that instantly captures Tony's dark imagination. Tony leads his own forces to destroy the North Side gangs and take over their market, even to the point of impersonating police officers to gun down several rivals in a garage. Tony kills Gaffney as he makes a strike at a bowling alley. The South side gang and Poppy go to a club and Tony and Poppy dance together in front of Johnny. After Tony conspicuously shows his intention to steal Poppy, Johnny believes that his protégé is trying to take over, and he arranges for Tony to be assassinated while driving in his car. Tony manages to escape this attack, and he and Guino kill Johnny, leaving Tony as the undisputed boss of the city. In order to elude the increasingly aggravated police force, Tony and Poppy leave Chicago for a month.

Tony's actions have provoked a public outcry, and the police are slowly closing in. After he sees his beloved sister Francesca ("Cesca") with Guino, he kills his friend in a jealous rage before the couple can inform him of their secret marriage. His sister runs out distraught and tells the police what he has done. The police move to arrest Tony for Guino's murder, and Tony holes up in his house and prepares to shoot it out. Cesca comes back, planning to kill him, but ends up helping him to fight the police. Tony and Cesca arm themselves and Tony begins shooting at the police from the window, laughing maniacally. Moments later, however, Cesca is killed by a stray bullet. Calling Cesca's name as the apartment fills with tear gas, Tony leaves down the stairs, and the police confront him. Tony pleads for his life, but then makes a break for it, only to be gunned down by an unknown officer with a Tommy gun. He stumbles for a moment and then falls down in the gutter and dies. Among the sounds of cheering, outside, the electric billboard blazes "The World is Yours."

Cast

- Paul Muni as Antonio "Tony" Camonte

- Ann Dvorak as Francesca "Cesca" Camonte

- George Raft as Guino Rinaldo

- Osgood Perkins as John "Johnny" Lovo

- Karen Morley as Poppy

- Boris Karloff as Tom Gaffney

- C. Henry Gordon as Inspector Ben Guarino

- Vince Barnett as Angelo

- Purnell Pratt as Garston

- Tully Marshall as Managing editor

- Inez Palange as Mrs. Camonte

- Edwin Maxwell as Chief of Detectives

- Harry J. Vejar as Big Louis Costillo (uncredited)[3]

- Howard Hawks as Man on Bed (uncredited)[4]

Production

Background and development

Multimillionaire business tycoon Howard Hughes, who occasionally dabbled in filmmaking, wanted to make a box office hit after his success with the film The Front Page. Gangster films had become popular in the early 1930s in the age of Prohibition and Hughes wanted to make a gangster film based on the life of Al Capone that would be superior to all other films in the genre. He was strongly advised against making the film, because there had been many gangster films made since sound movies had been invented. Little Caesar and The Public Enemy were already popular films; Warner Bros. claimed that there was nothing new that could be done with the gangster genre. Furthermore, censors in the industry were becoming concerned with the glamorization of the dangerous and illicit life of gangsters in media. Despite all this, Hughes bought the rights to the Armitage Trail's novel Scarface, which was inspired by the life of Al Capone.[5] Trail (pseudonym for Maurice Coons) wrote for a number of detective story magazines during the early 20s, but died of a heart attack at the age of 28, shortly before the release of the 1932 film.[6] Overall, the novel bears little resemblance to the film.[5] However, the film contains the same major characters, plot points and incestual undertones as the novel and changes were made in order to reduce the length of the film, the number of characters, and to satisfy the requests of censorship offices. Generally, Tony's character was made to appear less intelligent and more brutish than his counterpart in the novel. This was done to make the gangster character look less admirable due to the danger of portraying criminals with positive characteristics recognized by censorship offices. Similarly, the sibling relationship between Tony and the police officer from the novel was removed to avoid showing corruption of law enforcement.[7]

Hughes managed to hire Fred Pasley, a New York reporter and authority on Capone, as a writer. Howard Hughes asked Ben Hecht, the first winner of the Academy Award for best original screenplay in 1929 for his silent crime film Underworld (1927 film), if he would write the screenplay.[8] Suspicious of Hughes as an employer, Hecht strictly requested that he would only write if he was paid one thousand dollars every day at six o'clock. Hecht claimed that this way, he would only waste a day's labor if Hughes turned out to be a fraud.[9] Howard Hughes wanted prominent film director Howard Hawks to direct and co-produce the film.[10] Hughes admired Hawks's Film The Dawn Patrol, even though he had previously attempted to prevent the release of the film claiming that Hawks had ripped off his film Hell's Angels. Hawks was surprised by the job offer as the only encounters with Hughes that he had were poor, including when Hughes tried suing him because he had become interested in a play that Hughes had already bought the rights to for filming. Hughes attempted to persuade Hawks during a game of golf. Hughes promised to drop the lawsuit, and by the eighteenth hole, Hawks was more willing to direct the film. Hawks became even more convinced to work on the film when he found out that Ben Hecht would be the head writer.[11] Hecht and Hawks worked together well, both interested in the idea of portraying the Capones as if they were from the House of Borgia, including echoing and augmenting a subtle hint of incest between the main character and his sister also present in Trail's novel.[12]

The film was adapted by Hecht in eleven days in January 1931 from Trail's novel. Additional writing was provided by Fred Pasley and W. R. Burnett, author of the novel Little Caesar upon which the 1931 film of the name name was based. Fred Pasley wrote the screenplay with influences from Pasley's own book Al Capone: Biography of a Self-Made Man that begins with a barbershop scene with Al Capone similar to the one introducing Tony Camonte in the film. John Lee Mahin and Seton I. Miller rewrote and altered the script for continuity and dialogue. Pasley was not credited for his work on the film.[13] Because there were five writers, it is difficult to distinguish which components were contributed by which writer; however, the ending of Scarface is similar to Hecht's first gangster film Underworld where gangster Bull Weed traps himself in his apartment with his lover and shoots it out with hordes of police outside, and thus was likely a Hecht contribution.[14]

Ties to Capone

Both the film and novel are loosely based upon the life of Al Capone, whose nickname was "Scarface".[15] In his memoir about his time as a young reporter in Chicago, Gaily, Gaily (1963), Ben Hecht reminisced about having known "Big Jim" Colosimo socially and briefly meeting a young Capone.[16] He also said that Capone sent two of his men to visit him to make sure that the film was not based on Capone's life.[9] He told them that the character of "Scarface" was a parody of numerous people with whom he was acquainted. He claimed that the reason that he called it "Scarface" was not because it was about Capone (which it was), but because Capone was one of the most famous men of the time and that title would intrigue people to go see the film. After that, the two left him alone.[9] However, the film was intended to be a biopic and the names of the characters and locations were changed only minimally in order to maintain historical accuracy of the film. Capone became Camonte and Moran became Doran. According to some of the original scripts, Colosimo was intended to be changed to Colisimo and O'Bannion was intended to be changed to Bannon, but later the names were changed to Costillo and O'Hara respectively. This, including other alterations made to characters and other identifying locations to maintain anonymity, were due to censorship and Hawks's concern about the overuse of historical details.[17]

There are many obvious references to Capone and actual events from the Chicago gang wars, especially to audiences at the time of the film's release. First, Capone had a large, visible scar on the side of his face, like the Paul Muni character. The film reveals that Tony got the scar in a barroom brawl. Capone received his scar in a similar way: in a bar fight at the Harvard Inn after making a pass at a patron's sister.[18] Also, the police in the film mention that Camonte is a member of the Five Points Gang in Brooklyn, of which Capone was a known member.[19][20] Another example is that Tony kills his boss "Big Louis" Costillo in the lobby of his club; Capone was involved in the murder of his first boss "Big Jim" Colosimo in 1920.[21] Moreover, rival boss O'Hara is murdered in his flower shop; Capone's men murdered Dean O'Bannion in his flower shop in 1924.[22] In addition, the assassination of seven men in a garage, with two of the gunmen costumed as police officers, mirrors the St. Valentine's Day Massacre of 1929. Additionally, the leader of this rival gang in the film (Karloff) narrowly escapes the shooting, which is precisely what happened to gang leader Bugs Moran in the actual St. Valentine's Day Massacre.[23] Finally, the beginning shot of the film shows a streetlight and an intersection: 22nd Street and Wabash Avenue which was located in the middle of Capone's South Side and served as the site for many of Capone's crimes.[24]

Despite the clear references to Al Capone in the film, Capone was rumored to have liked the film so much that he owned a print of it.[25] Ironically, Capone was imprisoned in Atlanta for tax evasion during the film's release.[22]

Casting

Hawks and Hughes had a difficult time casting popular actors, because most of them were under contract and studios were reluctant to let their actors freelance to independent producers.[26] Irving Thalberg first suggested that Hawks consider Clark Gable, but Hawks felt that Gable was a personality, not an actor.[27] After having seen Muni on Broadway, talent agent Al Rosen suggested that Hughes consider Paul Muni for the lead role. When Muni was first asked if he would be interested in the role of Tony, he declined, feeling that he wasn't physically suited for the role. After reading the script, his wife Bella urged him that it would be a good opportunity.[28] After a test run in New York, Hughes, Hawks, and Hecht approved Muni for the role.[29] Critics didn't agree with the casting of British actor Boris Karloff as British gangster Gaffney, believing that his accent was out of place in a gangster film. However, some critics considered him a high point of the film.[30] Jack La Rue was originally chosen to play Tony Camonte's sidekick Guino Rinaldo, but because he was taller than Muni, Hawks was worried that La Rue would overshadow Muni's tough Scarface persona.[27] George Raft, a struggling actor at the time, was chosen instead to play character Guino Rinaldo, modeled after Al Capone's bodyguard Frank Rio, after Hawks encountered him at a prizefight.[31]

Even though Karen Morley was under contract at MGM, Hawks was close with MGM studio executive Eddie Mannix, who loaned out Morley for the film. She was reportedly given the choice between the role of Poppy or Cesca. She forewent the stronger role of Cesca, because she wanted to help her friend Ann Dvorak's film career and she thought Dvorak might be better fit for the role of Cesca. She considered this, "probably the nicest thing [she] did in [her] life".[32] Morley invited twenty-year old Dvorak to a party at Howard Hawks' house in order to introduce them. According to Hawks, at the party, Dvorak zeroed in on George Raft who would be playing her love interest in the film. He initially declined her invitation to dance. She tried to dance in front of him in order to lure him; eventually he gave in, and their dance together stopped the party.[33] After this event, Hawks was interested in casting her, but had reservations about her lack of experience. After a screen test, he gave her the part, and MGM was willing to release her from her contract as a chorus girl.[34] Dvorak had to both receive permission from her mother Anna Lehr and to win a petition presented to the Superior Court to be able to sign on with Howard Hawks as a minor.[35]

Filming

Filming lasted six months, which was long for films made in the early 1930s.[36] Howard Hughes remained off-set to avoid interfering with the filming of the movie. Hughes urged Hawks to make the film as visually exciting as possible by adding car chases, crashes, and machine gun fire.[37] Hawks shot the film at three different locations: Metropolitan Studios, Harold Lloyd Studios and the Mayan Theater in Los Angeles. Shooting took three months with the cast and crew working seven days a week. For the most violent scene of the film in the restaurant, Hawks cleared the set to avoid harming extras and then had the set fired on by machine guns. The actors acted out the scene in front of a screen with the shooting projected in the back, so as everyone crowded under the tables in the restaurant, it looked like the room was simultaneously under fire.[38]

During filming, Hawks and Hughes met with the Hays Office to discuss revisions. Despite that, Scarface was still filmed and put together quickly. In September 1931, a rough cut of the film was screened for the Production Code Administration and the film was subsequently shown to the California Crime Commission and police officials, none of whom thought the movie was a dangerous influence for audiences or would illicit a criminal response. Irving Thalberg was given an advanced screening and was impressed by the film. Among all the positive feedback the film was given, the Hays Office was insistent on changes before final approval.[39]

Censorship

Scarface was produced and filmed before the Motion Picture Association (MPAA) was founded and before the "R" rating was established. Will Hays was the chairman of the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) at the time. This board later became known as the Hays Office. The goal of the Hays office was to censor out nudity, sexuality, drug use and crime.[40] More specifically, the Hays Office wanted to avoid the sympathetic portrayal of crime by either showing criminals recognizing the error of their ways or showing the criminals get punished.[41] J.E. Smyth called Scarface, "one of the most highly censored films in Hollywood history."[42] Howard Hawks believed the censorship office had personal vendettas against the movie specifically, while Hughes believed the censorship was due to "ulterior and political motives" of corrupt politicians.[43] However, James Wingate of the New York censor boards rebutted that Hughes was preoccupied with "box office publicity" in producing the film.[44] After repeated demands for a script rewrite from the Hays Office, Hughes ordered Hawks to shoot the film, "Screw the Hays Office, make it as realistic, and grisly as possible."[45] The Hays Office was outraged by Scarface when they screened it. The Hays office called for scenes to be deleted, scenes to be added that condemn gangsterism, and a different ending. They believed that Tony's death at the end of the film was too glorifying. In addition to the violence, the MPPDA felt that an inappropriate relationship between the main character and his sister was too overt, especially in one scene where he holds her in his arms after he slaps her and tears her dress; they ordered this scene be deleted. Hughes, in order to receive the MPPDA's approval, deleted some of the more violent scenes, added a prologue to condemn gangsterism, and wrote a new ending.[46] In addition, a couple scenes were added to overtly condemn gangsterism such as a scene in which a newspaper publisher looks at the screen and directly admonishes the government and the public for their lack of action in fighting against mob violence and a scene in which the chief detective denounces the glorification of gangsters.[47] Hawks refused to shoot the extra scenes and the alternate ending so they were directed by Richard Rossen, earning Rossen the title of "co-director".[48] Hughes was instructed to change the title to The Menace, Shame of the Nation or Yellow to clarify the subject of the film; after month of haggling, he compromised by titling it Scarface, Shame of the Nation and adding a foreword condemning the "gangster" in a general sense.[49] Hughes also made an attempt to release the film under the title "The Scar" when the original title was disallowed by the Hays office.[50] Besides the title, the term "Scarface" was removed completely from the film. In the scene where Tony kills Rinaldo, Cesca says the word "murderer", but she can be seen actually mouthing the word "Scarface".[51]

The original script had Tony's mother loving her son unconditionally, praising his lifestyle, and even accepting money and gifts from him. In addition, there was a politician who, despite campaigning against gangsters on the podium, is shown partying with them after hours. The script ending had Tony staying in the building, unaffected by tear gas and a multitude of bullets fired at him. It is not until the building is on fire that Tony is forced to exit the building, guns blazing. He is sprayed with police gun fire but appears unfazed. Upon noticing the police officer who had been arresting him throughout the film, he fires at him, only to hear a single "click" noise implying that his gun is empty. He is then killed after being shot several times by said police officer. A repeated clicking noise is heard on the soundtrack implying that he was still attempting to fire while he was dying.[45]

Alternate ending

The first version of the film (Version A) was completed on September 8, 1931, but censors required that the ending be modified or they would refuse to grant Scarface a license. Paul Muni was unable to re-film the ending in 1931 due his work on Broadway. To combat this Hawks used a body double. The body double was mainly filmed by way of shadows and long shots in order to mask the fact that Muni was not in the ending of the film.[52] The alternate ending (Version B) differs from the original ending in the manner that Tony is caught and in which he dies. Unlike the original ending where Tony escapes the police and dies after getting shot several times, the alternate ending starts with Tony reluctantly handing himself over to the police. After the encounter, Tony's face is not shown again. A scene follows where a judge is addressing Tony during sentencing. The next scene is the finale, in which Tony (seen from a bird's eye view) is brought to the gallows, where he is finally put to an end by being hanged.[53]

However, Version B still did not pass the New York censors and Chicago censors. Howard Hughes felt the Hays office had suspicious intentions in rejecting the film, because Hays was friends with Louis B. Mayer and Hughes believed censorship was to prevent wealthy independent competitors from producing films. Confident that his film could stand out among audiences more than Mayer's films, Hughes organized a press showing of the film in Hollywood and New York.[54] The New York Herald-Tribune praised Hughes for his courage to stand up against censors. Hughes disowned the censored film and finally in 1932 released Version A—with the added text introduction in states that lacked strict censors (Hughes also attempted to take the New York censors to court). This 1932 release version led to bona-fide box office status and positive critical reviews. Hughes was successful in subsequent lawsuits against the boards that censored the film.[55][56] Due to criticism from the press, Hays claimed that the version being shown in theaters was actually the censored film that he had previously approved.[54]

Music

Due to the film's urban setting, nondiegetic music (not visible on the screen or implied to be present in the story) was not used in the film.[57] The only music that appears in the film is during the opening and closing credits and during scenes in the movie where music would appear naturally in the film's action such as in the nightclub. Adolf Tandler served as the film's musical director, while Gus Arnheim served as the orchestra's conductor. Gus Arnheim and his Cocoanut Grove Orchestra perform "Saint Louis blues" by W. C. Handy and "Some of These Days" by Shelton Brooks in the nightclub.[58] The tune that Tony whistles in the film is the sextet from Gaetano Donizetti's popular opera Lucia di Lammermoor.[5] This tune is accompanied by words that translate to, "What restrains me in such a moment?", and this tune continues to appear during violent scenes in the movie.[59] The song Cesca sings while playing the piano is "Wreck of the Old 97".[60]

Cultural references

The serious play that Tony and his friends go to see, leaving at the end of Act 2, is John Colton and Clemence Randolph's Rain, based on W. Somerset Maugham's story "Miss Sadie Thompson". The play opened on Broadway in 1922 and ran throughout the 1920s. (A film version of the play, also titled Rain and starring Joan Crawford, was released by United Artists the same year as Scarface.)[61] Though fairly inconspicuous in the film, and unnoticed by most viewers, the Capone family was meant to be partially modeled after the Italo-Spanish Borgia family. This was most prominent thought the subtle and arguably incestuous relationship that Tony Camonte and his sister share.[12] Camonte's excessive jealousy of his sister's affairs with other men hint at this relationship.[62] Coincidentally, Donizetti wrote the opera for Lucrezia Borgia, about the Borgia family, and Lucia di Lammermoor from where Tony Camonte's whistle tune comes.[63]

Release

After battling with censorship offices, the film was released almost a year late, behind The Public Enemy and Little Caesar which had been filmed at the same time. Scarface was released in theaters on April 9, 1932.[42] Due to the fact that each state had a different board of censors, the film was released with the original ending in some states and was released with the alternate ending in others.[64] The film was released on DVD on May 22, 2007, and was released again on August 28, 2012, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of Universal Studios, by Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Both versions of the DVD include an introduction by Turner Classic Movies host and film historian Robert Osborne and the film's alternate ending.[65][66] On video and on television, the film maintains Hawks's original ending but still contains the other alterations he was required to make during filming.[67] A completely unaltered and uncensored version of the film is not known to exist.[68]

Reception

On the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes, Scarface holds a 100% "Fresh" rating with all 27 reviews being positive.[69] At the time of release, audience reception was generally positive.[37] According to George Raft, who met Al Capone a few times at casinos, even Capone himself liked the film adding, "you tell 'em that if any of my boys are tossin' coins, they'll be twenty-dollar gold pieces."[70] Variety cited Scarface as having, "that powerful and gripping suspense which is in all gangster pictures is in this one in double doses and makes it compelling entertainment," and that the actors play, "as if they'd been doing nothing else all their lives."[71] The National Board of Review named Scarface as one of the best pictures of 1932.[72] However, at the time of release in 1932, there was a general public outcry about the film and the gangster genre in general which negatively affected box office earnings of the film.[73] Jack Alicoate gave Scarface a scathing review in The Film Daily saying the violence and subject matter of the film left him with, "the distinct feeling of nausea". He goes on to say the film, "should never have been made" and showing the film would, "do more harm to the motion picture industry, and every one connected with it, than any picture ever shown."[74] The film earned $600,000 at the box office and while Scarface was more of a financial success than some of Hughes's other films at the time, due to the large cost of production, it is unlikely that the film did any better than break even.[73]

The film initiated outrage among Italian organizations and individuals of Italian descent, because they remarked a tendency of filmmakers to portray gangsters and bootleggers in their films as Italian. In the film, an Italian American makes a speech condemning gangster activities; this was added later in production to appease censors. This, however, didn't prevent the Italian embassy from disapproving Scarface.[75] Believing the film to be offensive to the Italian community, the Order Sons of Italy in America formally denounced the film and other groups urged community members to boycott the film and other films derogatory towards Italians or Italian-Americans.[76] Will Hays wrote to the ambassador in Italy, excusing himself from scrutiny by stating that the film was an anachronism, because it had been held up in production for two years and didn't represent the current practice of censorship at the time.[75] Nazi Germany permanently prohibited showings of the film.[77] Some cities in England banned the film as well, believing the British Board of Film Classification's policy on gangster films was too lax.[64] Several cities in the United States including Chicago and some states refused to show the film. The magazine Movie Classics ran an issue urging the people to demand to see the film at theaters despite the censorship bans.[78] The film broke box office records at the Woods Theatre in Chicago after premiering Thanksgiving Day, November 20, 1941 after having been banned from showing in Chicago by censors for nine years.[79] Despite the favorable reception of the film among the public, the censorship battles and the unflattering reviews from some press contributed to the film's generally poor performance at the box office. Upset at the inability to make money from Scarface, Howard Hughes removed the film from circulation.[47] The film remained unavailable until 1979 except for occasional release prints of suspect quality from questionable sources.[80]

Hughes had plans in 1933 to direct and produce a sequel to Scarface, but due to strict censorship rules, the film was never made.[81]

Industry reception

In 1994, Scarface was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[82] The character of Tony Camonte ranked at number 47 on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains list.[83] The film was named the best American sound film by critic and director Jean-Luc Godard in Cahiers du Cinéma.[84][85] In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "Ten Top Ten"—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Scarface was acknowledged as the sixth best in the gangster film genre. The 1983 version was placed 10th, making Scarface the only film to make the same "10 Top 10" list as its remake.[86]

Analysis

The classification of Scarface as a film with historical significance or as merely a Hollywood gangster-era flick has been greatly debated by scholars.[87] Its historical significance was augmented by the film's writing credits: W.R. Burnett, author of gangster novel Little Caesar from which the film of the same name was based on, Fred D. Pasley, a prominent Chicago gangland historian, and ex-Chicago reporter Ben Hecht.[88] Events similar to the assassination of Jim Colismo and the St. Valentine's Day Massacre contribute to the film's realism and authenticity.[62] Film critic Robert E. Sherwood stated that the film, "merits...as a sociological or historical document...[and] an utterly inexcusable attempt has been made to suppress it—not because it is obscene...but because...it comes to close to telling the truth."[89]

Excess

According to film studies professor Fran Mason, one of the most prominent themes of the film is excess. The opening of the film sets the stage as Big Louie Costillo sits in the remnants of a wild party, convincing his friends that his next party will be bigger, better, and have "much more everything".[90] This indicates the excessive life of a gangster, whether in pleasure or in violence. The death scene of Costillo sets the next tone of excess. In this scene, the audience only sees the shadow of Tony Camonte with a gun, hears the shots and the sound of the body hitting the floor. The violent scenes become more severe as the film progresses. Most of the violence in the film is shown through montage, as scenes go by in sequence, showing the brutal murders that Tony and his gang commit such as roughing up bar owners, a drive by bombing, and the massacre of seven men up against a wall. There is a scene in which a peel-off calendar shown rapidly changing dates is being shot by a machine gun, making the excessive violence clear. The violence is not only perpetrated by the gangsters. The police in the final scene with Tony and Cesca spare no effort to catch the notorious Camonte siblings, visible through the disproportionate number of police officers and cars surrounding the apartment complex to apprehend one man. Tony and the police's excessive use of violence throughout the film normalizes it.[91] An element of parody underlies Tony's excessive and abnormal joy in using Tommy guns. In the scene in the restaurant in which men from the North side gang attempt to shoot Tony down with a Tommy, he obtains pleasure from the power. Rather than cowering beneath the tables, he tries to peek out to watch the guns in action, laughing maniacally from his excitement. He reacts jovially upon getting his first Tommy gun and enthusiastically leaves to, "write [his] name all over the town with it."[92]

The gangster's excessive consumption is comically represented through Tony's quest to obtain expensive goods and show them off. In Tony's first encounter with Poppy alone on the staircase, he boasts about his new suit, jewelry, and bullet-proof car. Poppy largely disregards his advances calling his look, "kinda effeminate".[92] His feminine consumption and obsession with looks and clothes is juxtaposed by his masculine consumption which is represented by his new car. Later, Tony shows Poppy a stack of new shirts, claiming that he will wear each shirt only once. His awkwardness and ignorance of his own exorbitance makes this Gatsby style scene more comical than serious. His consumption serves to symbolize the disintegration of values of modernity, specifically represented by his poor taste and obsession with money and social status. Tony's excessiveness transcends parody and becomes dangerous, because he represents a complete lack of restraint that ultimately leads to his downfall.[93]

Tony's excess is also manifest in the gang wars in the city. He is given express instruction to leave O'Hara, Gaffney, and the rest of the North side gang alone. He disobeys because of his lust for more power, violence, and territory. Not only does he threaten the external power structure of the gangs in relation to physical territory, he also disrupts the internal power structure of his own gang by blatantly disobeying his boss Johnny Lovo.[94] Gaffney's physical position juxtaposes that of Tony. Throughout the film, Gaffney's movement is restricted by both setting and implication because of the crowded spaces in which he is shown onscreen and his troupe of henchmen that he is constantly surrounded by. Although Tony is able to move freely in the beginning of the film, by the end he has become just as confined and restricted as Gaffney. He is surrounded by henchmen and cannot move as freely throughout the city. This, however, is self-imposed by his own excessive desire for territory and power.[94]

The theme of excessiveness is further exemplified by Tony's incestuous desires for his sister, Cesca, whom he attempts to control and restrict. Their mother acts as the voice of reason, but Tony does not listen to her, subjecting his family to the excess and violence that he brings upon himself.[94] His lust for violence mirror's Cesca's lust for sexual freedom, symbolized by her seductive dance for Rinaldo at the club. Rinaldo is split between his loyalty for Tony and his passion for Cesca, serving as a symbol of the power struggle between the Camonte siblings. Rinaldo is also a symbol of Tony's power and prominence; his murder signifies Tony's lack of control and downfall, which ends in Tony's own death.[95]

American Dream

Camonte's rise to prominence and success is modeled after the American Dream, but more overtly violent. As the film follows the rise and fall of the Italian gangster, Tony becomes increasingly more Americanized. When Tony comes up from under the towel at the barbershop, this is the first time the audience gets a look at his face. He appears foreign with a noticeable Italian accent and slicked hair and an almost Neanderthal appearance with the scars on his cheek.[59] As the movie progresses, he becomes more Americanized as he loses his accent and his suits change from gaudy to elegant.[59] By the end of the film, his accent is hardly noticeable. Upon the time of his death, he had accumulated many "objects" that portray the success suggested by the American Dream: his own secretary, a girlfriend of significant social status (more important even is the fact that she was the mistress of his old boss), as well as a fancy apartment, big cars, and nice clothes. Camonte exemplifies the idea of the American Dream that one can obtain success in America by following Camonte's own motto to, "Do it first, do it yourself, and keep on doin' it."[96] On the other hand, Camonte represents the American urge to reject modern life and society, in turn rejecting Americanism itself. The gangster strives for the same American Dream as anyone else, but through violence and illicit activity, approaches it in a way that is at odds with modern societal values.[97]

Gangster territory

Control of territory is a theme in the gangster film genre of both a physical sense and on the movie screen. Tony works to control the city by getting rid of competing gangs and gaining literal physical control of the city, but he also gains control of the movie screen in his rise to power. This is most evident in scenes and interactions involving Tony, Johnny, and Poppy. In an early scene in the film, Tony comes to Johnny's apartment to receive his payment after killing Louie Costillo. There are two visible rooms in the shot, the main room, where Tony sits and the room in the background where Poppy sits and where Johnny keeps his money. Lovo goes into the back room but Tony does not, so this room represents the power and territory that Johnny controls but Tony does not. The men are sitting across from each other in the scene with Poppy sitting in the middle of them in the background representing the trophy that they are both fighting for. However, the fact that they are both equally taking up room in the shot represents their equality of power at that point. Later, in the nightclub scene, Tony sits himself in between Poppy and Johnny showing that he is in control through his centrality in the shot. At this point, he has achieved the most power and territory, as indicated by "winning" Poppy.[98]

Fear of technology

Ideas in Scarface represent the American fears and confusion that stemmed from the technological advancement of the time: whether technological advancement and mass production should be feared or celebrated. There was an overall anxiety of the time about whether new technology would cause ultimate destruction in the future or whether it would help make lives easier and bring happiness. In the film, Tony excitedly revels in the possibilities that machine guns can bring by killing more people, more quickly and from further away. This represents the question of whether mass production equals mass destruction or mass efficiency.[99]

Objects and gestures

The use of playful motifs throughout the film showcased Howard Hawks's dark comedy he expressed through his directing.[62] In the bowling alley scene, where rival gang leader Tom Gaffney was murdered, when Gaffney throws the ball, the shot remains on the last standing bowling pin, which falls to represent the death of kingpin Tom Gaffney. In that same scene, before the death of Gaffney, a shot shows an "X" on the scoreboard, foreshadowing that Gaffney would die.[100] Hawks used the "X" foreshadowing technique 15 to 20 times throughout the film (seen first in the opening credits) that was chiefly associated with death appearing many times (but not every scene) when a death is portrayed; the motif shows up in numerous places, most prominently as Tony's "X" scar on his left cheek.[5] The motifs in the film serve to mock the life of the gangster.[62] The gangster's hat is a common theme throughout gangster films specifically Scarface as representative of conspicuous consumption.[101] Hand gestures were a common motif that Hawks included in his films. In Scarface, George Raft was instructed to repetitively flip a coin, which he does throughout the film.[102]

"The World is Yours"

Camonte's apartment looks out on a neon, flashing sign that says "The World Is Yours". This sign represents the modern American city as a place of opportunity and individualism. As attractive as the slogan is, the message is impossible, yet Tony doesn't understand this. The view from his apartment represents the rise of the gangster. When Camonte is killed in the street outside his building, the camera pans up to show the billboard, representative of the societal paradox of the existence of opportunity yet the inability to achieve it.[103] According to Robert Warshow, the ending scene represents how the world is not ours, but not his either. The death of the gangster momentarily releases us from the idea of the concept of success and the need to succeed.[104] In regards to the theme of excess, the sign is a metaphor for the dividing desires created by modernity seen through the lens of the excessive desires of the gangster persona.[95]

Style

"Sharp" and "hard-edged", Scarface set the visual style for the gangster films of the 1930s.[105] Hawks created a violent, gripping film through his use of strong contrast of black and white in his cinematography, for example, dark rooms, silhouettes of bodies against drawn shades, and pools of carefully placed light. Much of the film is shown to take place at night. Tight grouping of subjects within the shot and stalking camera movement followed the course of action in the film.[59] The cinematography is dynamic and characterized by highly varied camera placement and mobile framing.[106]

Legacy

Despite its lack of success at the box office, Scarface was one of the most discussed films of 1932 due to its subject matter, and its struggle and triumph over censor boards.[89] Scarface is cited (often along with Little Caesar and The Public Enemy) as the archetype of the gangster film genre, because it set the early standard for the genre of gangster films that have continued to appear in Hollywood.[107] However, Scarface would be the last of the three big gangsters films of the early 1930s, as the outrage at the pre-Code violence caused by the three films, particularly Scarface sparked the creation of the Production Code Administration in 1934.[108] Howard Hawks cited Scarface as one of his favorite works and the film was an subject of pride for Howard Hughes. Hughes locked the film up in his vaults a few years after it was released, refusing many profitable offers to distribute the film or to buy its rights. After his death in 1976, filmmakers were able to gain access to the rights to the film which sparked the 1983 remake starring Al Pacino.[109]

Paul Muni's performance in Scarface as "the quintessential gangster anti-hero" contributed greatly to his rapid ascent into his acclaimed film career.[110] Paul Muni received significant accolades for his performance as Tony Camonte. Critics praised Muni for his robust and fierce performance.[29] Al Pacino stated that he was greatly inspired by Paul Muni and that Muni influenced his own performance in the 1983 Scarface remake.[111] However, despite the impressive portrayal of a rising gangster, critics claim that the character minimally resembled Al Capone. Unlike Camonte, Capone avoided grunt work and typically employed others to do his dirty work for him. Moreover, Muni's Scarface at the end revealed the Capone character to be a coward as he pled for mercy and then tried to run for it before getting shot in the street. Capone wasn't known for his cowardice and didn't die in battle.[112]

Scarface would be Ann Dvorak's best and most well-known film.[113] The film launched Raft's lengthy career as a leading man. Raft, in the film's second lead, had learned to flip a coin without looking at it, a trait of his character, and he made a strong impression in the comparatively sympathetic but colorful role. It was Howard Hawks's idea to get Raft to use this in the film to camouflage his lack of acting experience.[114] A reference is made in Raft's later role as gangster Spats Columbo in Some Like it Hot (1959), wherein he asks a fellow gangster (who is flipping a coin) "Where did you pick up that cheap trick?"[115]

The movie Scarface had an influence on actual gangster life four years after the film was released. In 1936, Jack McGurn who was thought to be responsible for the St. Valentine's Massacre depicted in the film, was murdered by rivals in a bowling alley.[116]

Italian language versions

In October 1946, after World War II and the relations between Italy and the United States softened, Titanus, an Italian film production company was interested in translating Scarface into Italian. Initially, upon requesting approval from the Italian film office, the request was rejected due censorship concerns of the portrayal of violence and crime throughout the film. There was no initial concern about the film's portrayal of Italians.[117] Titanus appealed to the Italian film office calling Scarface, "one of the most solid and constructive motion pictures ever produced overseas".[118] They lobbied that bringing in a foreign language film would help save domestic film producers money in the Italian economy damaged by the recent war. After receiving approval at the end of 1946, Titanus translated a script for dubbing the film.[118] One difference in the Italian script versus the American script is that the names of the characters were changed from Italian sounding to more American sounding. For example, Tony Camonte was changed to Tony Kermont, and Guino Rinaldo was changed to Guido Reynold.[118] This, and several other changes were made to conspicuously remove any reference to Italians. Another example is the difference in the scene in the restaurant with Tony and Johnny. In the American version, Tony makes an comical statement about the garlic in the pasta, whereas in the Italian translation, the food in question is a duck liver pâté, a less overtly Italian reference to food.[119] Moreover, in the American version, the gangsters are referred to as illegal immigrants by the outraged community; however, in the Italian dubbed version, the citizen status of the criminals is not mentioned but merely the fact that they are repeat offenders.[120]

The film was redubbed into Italian in 1976 by the broadcasting company Radio Televisione Italiana (RAI) with a new script translated by Franco Dal Cer and dubbing directed by Giulio Panicali. Pino Locchi dubbed the voice of Tony Camonte for Paul Muni and Pino Colizzi dubbed the voice of Gunio Rinaldo for George Raft. A difference between the 1947 version and the 1976 version is that all of the Italian names are and Italian cultural references were untouched and stayed true to the original American script.[121] The 1976 version celebrates the Italian backgrounds of the characters, even going as far to add some noticeably different Italian dialects to specific characters.[122] This version of the dubbed film translates the opening and closing credit scenes as well as the newspaper clippings shown into Italian; however, the translation of the newspaper clippings were not done with particular aesthetic care.[123]

The film was redubbed one more time sometime in the 1990s and released on the Universal's digital edition. The consensus from scholars is that the 1990 dub is a combination of re-voicing and reuse of audio from the 1976 redub.[124]

Related films

After the rights for Scarface were obtained after the death of Howard Hughes, Brian de Palma released a remake of the film in 1983 featuring Al Pacino as Scarface. The film was set in contemporary Miami and is known for its inclusion of graphic violence and obscene language, uncharacteristic of the 1932 film.[55][125] The 2003 DVD "Anniversary Edition" limited edition box set of the 1983 film included a copy of its 1932 counterpart. At the end of the 1983 film, a title reading "This film is dedicated to Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht" appears over the final shot.[126][127][128]

Universal announced in 2011 that the studio is developing a new version of Scarface. The studio claims that the new film is neither a sequel nor a remake, but will take elements from both the 1932 and the 1983 version, including the basic premise of a man who becomes a kingpin in his quest for the American Dream. Martin Bregman produced the 1983 remake, and he will produce this new version, as well.[129] David Ayer will write the screenplay.[130] On August 11, 2016, it was announced that Antoine Fuqua is in talks to direct the remake.[131] On February 10, 2017, Fuqua left the remake and the Coen brothers are rewriting the script.[132] As of 2018, Fuqua was back on the project.[133]

Scarface has been associated with other films of the classic sound gangster films era. Scarface is often associated with other Pre-Code gangster films released in the early 1930s such as The Doorway to Hell (1930), Little Caesar (1931) and The Public Enemy (1931).[134] According to Fran Mason of the University of Winchester, Scarface is more similar to the film The Roaring Twenties than its early 1930s gangster film contemporaries, because of its excessiveness.[135]

See also

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

References

- ↑ "SCARFACE (A)". British Board of Film Classification. May 7, 1932. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars. 1. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-299-23004-3. OCLC 262883574.

- ↑ Eagan 2010, p. 192.

- ↑ Parish & Pitts 1976, p. 347.

- 1 2 3 4 Dirks, Tom. "Scarface: The Shame of the Nation". Filmsite Movie Review. American Movie Classics Company. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Server 2002, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Roberts 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Clarens 1980, p. 84; Thomas 1985, p. 70; Kogan, Rick (February 25, 2016). "Remembering Ben Hecht, the first Oscar winner for original screenplay". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Hecht 1954, pp. 486–487.

- ↑ "Scareface (1932)". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas 1985, pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 Clarens 1980, p. 85.

- ↑ Smyth 2004, p. 552; Thomas 1985, p. 71; Clarens 1980, p. 85

- ↑ McCarty 1993, pp. 43, 67.

- ↑ Smyth 2006, pp. 75–77.

- ↑ Hecht 1963, p. 92.

- ↑ Smyth 2006, pp. 78, 380.

- ↑ Bergreen 1994, p. 49.

- ↑ Andrews, Evan. "7 Infamous Gangs of New York". History.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Doherty 1999, p. 148

- ↑ Langman & Finn 1995, pp. 227–228; "How Did Big Jim Colosimo Get Killed?". National Crime Syndicate. National Crime Syndicate. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Clarens 1980, p. 86.

- ↑ Langman & Finn 1995, pp. 227–228; O'Brien, John. "The St. Valentine's Day Massacre". Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 24, 2018. ; "St. Valentine's Day Massacre". History. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ↑ Smyth 2004, p. 554.

- ↑ MacAdams 1990, p. 128.

- ↑ Yablonsky 1974, p. 64.

- 1 2 Guerif 1979, pp. 48–52.

- ↑ Thomas 1985, p. 72.

- 1 2 Thomas 1985, p. 74.

- ↑ Bookbinder 1985, pp. 21–24.

- ↑ Yablonsky 1974, p. 64; Rice 2013, p. 52

- ↑ Rice 2013, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Rice 2013, pp. 3, 53.

- ↑ Rice 2013, p. 53.

- ↑ Rice 2013, p. 55.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 107; Bookbinder 1985, pp. 21–24

- 1 2 Thomas 1985, p. 75.

- ↑ Clarens 1980, p. 87.

- ↑ Rice 2013, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ "Howard Hawks' Scarface and the Hollywood Production Code". Theater, Film, and Video. PBS. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ↑ Smith 2004, p. 48.

- 1 2 Yogerst 2017, pp. 134–144.

- ↑ Yogerst 2017, pp. 134–144; Doherty 1999, p. 150

- ↑ Doherty 1999, p. 150.

- 1 2 Black 1994, p. 126.

- ↑ Thomas 1985, p. 75; Clarens 1980, p. 88

- 1 2 McCarty 1993, p. 68.

- ↑ Smith 2004, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Smyth 2006, p. 80; Clarens 1980, p. 89

- ↑ Hagemann 1984, pp. 30–40.

- ↑ Rice 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Thomas 1985, pp. 75; Smyth 2006, p. 80

- ↑ "Scarface: The Shame of the Nation (1932)". www.filmsite.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2018. ; Smith 2004, p. 44

- 1 2 Smyth 2004, p. 557.

- 1 2 Thomas 1985, p. 76

- ↑ "Cinema: The New Pictures: Apr. 18, 1932". TIME. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011.

- ↑ Slowik 2014, p. 229.

- ↑ "SCARFACE (1932)". The Library of Congress. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Clarens 1980, p. 93.

- ↑ Hagen & Wagner 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ "Rain". Film Article. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Langman & Finn 1995, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Ashbrook 1965, pp. 500–501; Grønstad 2003, pp. 399–400

- 1 2 Springhall 2004, p. 139.

- ↑ "Scarface (1932)". Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Universal City, California: Universal Studios. May 27, 2007. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Scarface, Universal Studios Home Entertainment, August 28, 2012, archived from the original on February 28, 2013, retrieved August 1, 2018

- ↑ Smith 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ Smith 2004, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ "Scarface (1932)" Archived November 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ↑ Yablonsky 1974, p. 76.

- ↑ "Scarface". Variety. May 24, 1932. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ↑ "The National Board of Review". The Hollywood Reporter. January 21, 1933. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- 1 2 Balio 2009, p. 111.

- ↑ Alicoate, Jack (April 14, 1932). ""Scarface"...a mistake". The Film Daily. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- 1 2 Vasey 1996, p. 218.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 109.

- ↑ Clarens 1980, p. 91.

- ↑ Donaldson, Robert. "Shall the Movies Take Orders from the Underworld" (April). Movie Classics. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ↑ ""Scarface" Breaks Record on "Premiere"". Charles E. Lewis. Showmen's Trade Review. November 29, 1941. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ↑ Brookes 2016, p. 27;Smith 2004, pp. 44–45

- ↑ "Hughes Will Produce Sequel to 'Scarface'". The Hollywood Reporter. January 27, 1933. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ↑ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Congress.gov. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ↑ "A Young Jean-Luc Godard Picks the 10 Best American Films Ever Made (1963)". openculture.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Johnson, Eric C. "Jean-Luc Godard's Top Ten Lists 1956–1965". alumnus.caltech.edu. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ Smyth 2004, p. 535.

- ↑ Smyth 2006, p. 76.

- 1 2 Smyth 2004, p. 558.

- ↑ Mason 2002, p. 25.

- ↑ Mason 2002, pp. 25–26.

- 1 2 Mason 2002, p. 26.

- ↑ Mason 2002, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 Mason 2002, p. 27.

- 1 2 Mason 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Clarens 1980, p. 95.

- ↑ Grieveson, Sonnet & Stanfield 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Mason 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Benyahia 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Phillips 1999, p. 46;Langman & Finn 1995, pp. 227–228

- ↑ Grieveson, Sonnet & Stanfield 2005, p. 173.

- ↑ McElhaney 2006, pp. 31–45; Neale 2016, p. 110

- ↑ Benyahia 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Warshow 1954, p. 191.

- ↑ Martin 1985, p. 35.

- ↑ Danks 2016, p. 46.

- ↑ Brookes 2016, p. 2; Hossent 1974, p. 14

- ↑ Grønstad 2003, p. 387.

- ↑ Thomas 1985, p. 76.

- ↑ Silver & Ursini 2007, p. 261;Thomas 1985, p. 74

- ↑ Leight, Elias (April 20, 2018). "'Scarface' Reunion: 10 Things we Learned at Tribeca Film Festival Event". Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ↑ Hossent 1974, p. 21.

- ↑ Rice 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ Aaker 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (2001). "That Old Feeling: Hot and Heavy". Time, Inc. Time. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Fetherling 1977, p. 96.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Keating 2016, p. 112.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 113.

- ↑ Keating 2016, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 115.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 116.

- ↑ Keating 2016, p. 117.

- ↑ Keating 2016, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ "Scarface (1983)". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ AP (2018). "Al Pacino, Brian de Palma reflect on legacy of "Scarface" 35 years later". CBS Interactive Inc. CBS News. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Chaney, Jen (2006). "'Scarface': Carrying Some Excess Baggage". The Washington Post Company. Washington Post. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Martin 1985, p. xii

- ↑ Fleming, Jr., Mike (September 21, 2011). "Universal Preps New 'Scarface' Movie". Deadline Hollywood. United States: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Fleming Jr., Mike (November 29, 2011). "David Ayer To Script Updated 'Scarface'". Deadline Hollywood. United States: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Fleming, Jr., Mike (August 10, 2016). "Antoine Fuqua Circling New 'Scarface' At Universal". Deadline Hollywood. United States: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ Wrap Staff (February 10, 2017). "Coen Brothers to Bring Back 'Scarface' in 2018". The Wrap. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ↑ Fleming Jr, Mike (February 26, 2018). "Antoine Fuqua Back in 'Scarface' Talks". Penske Business Media. Deadline. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ↑ Smyth 2006, p. 59.

- ↑ Mason 2002, p. 24.

Bibliography

- Aaker, Everett (2013). The Films of George Raft. McFarland & Company. p. 24.

- Ashbrook, William (1965). Donizetti. London: Cassell & Company.

- Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780299230043.

- Benyahia, Sarah Casey (2012). Crime. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9780415581417.

- Bergreen, Laurence (1994). Capone: The Man and the Era. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 49. ISBN 0671744569.

- Black, Gregory D. (1994). Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0521452996. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Bookbinder, Robert (1985). Classic Gangster Films. New York: Citadel Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 0806514671.

- Brookes, Ian, ed. (2016). Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. ISBN 9781844575411.

- Clarens, Carlos (1980). Crime Movies: From Griffith to the Godfather and Beyond. Toronto: George J. McLeod Ltd. ISBN 0393009408.

- Danks, Adrian (2016). "'Ain't There Anyone Here for Love?' Space, Place and Community in the Cinema of Howard Hawks". In Brookes, Ian. Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. p. 46. ISBN 9781844575411.

- Doherty, Thomas (1999). Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231110944.

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: Continuum. p. 192. ISBN 9780826418494. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- Fetherling, Doug (1977). The Five Lives of Ben Hecht. Lester and Orpen Limited. ISBN 0919630855.

- Grieveson, Lee; Sonnet, Esther; Stanfield, Peter, eds. (2005). Mob Culture: Hidden Histories of the American Gangster Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813535565.

- Grønstad, Asbjørn (2003). "Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's 'Scarface'". Nordic Journal of English Studies. 2 (2). Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- Guerif, Francois (1979). Le Film Noir Americain. Artigues-pres-Bordeaux: Editions Henri Veyrier. pp. 48–52. ISBN 2851992066.

- Hagemann, E.R. (1984). "Scarface: The Art of Hollywood, Not "The Shame of a Nation"". The Journal of Popular Culture (Summer): 30–40.

- Hagen, Ray; Wagner, Laura (2004). Killer Tomatoes: Fifteen Tough Film Dames. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 52. ISBN 9780786418831.

- Hecht, Ben (1954). A Child of the Century. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 486–487.

- Hecht, Ben (1963). Gaily, Gaily. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. p. 92.

- Hossent, Harry (1974). The Movie Treasury Gangster Movies: Gangsters, Hoodlums and Tough Guys of the Screen. London: Octopus Books Limited. ISBN 0706403703.

- Keating, Carla Mereu (2016). "'The Italian Color': Race, Crime Iconography and Dubbing Conventions in the Italian-language Versions of "Scarface" (1932)". Altre Modernita (Ideological Manipulation in Audiovisual Translation).

- Langman, Larry; Finn, Daniel (1995). A Guide to American Crime Films of the Thirties. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0313295328.

- MacAdams, William (1990). Ben Hecht: The man behind the legend. Scribner. p. 128. ISBN 0-684-18980-1.

- Martin, Jeffrey Brown (1985). Ben Hecht: Hollywood Screenwriter. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. ISBN 083571571X.

- Mason, Fran (2002). American Gangster Cinema: From Little Caesar to Pulp Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0333674529.

- McCarty, John (1993). Hollywood Gangland: The Movies' Love Affair with the Mob. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312093063.

- McElhaney, Joe (Spring–Summer 2006). "Howard Hawks: American Gesture". Journal of Film and Video. 58 (1–2): 31–45. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- Neale, Steve (2016). "Gestures, Movements and Actions in Rio Bravo". In Brookes, Ian. Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. p. 110. ISBN 9781844575411.

- Parish, James Robert; Pitts, Michael R. (1976). Taylor, T. Allan, ed. The Great Gangster Pictures. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 347. ISBN 0810808811.

- Phillips, Gene D. (1999). Major Film Directors of the American and British Cinema (Revised ed.). Associated University Presses. p. 46. ISBN 0934223599. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Rice, Christina (2013). Ann Dvorak: Hollywood's Forgotten Rebel. Lexington, KT: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813144269.

- Roberts, Marilyn (2006). "Scarface, The Great Gatsby, and the American Dream". Literature/Film Quarterly. 34 (1). Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- Server, Lee (2002). Encyclopedia of Pulp Fiction Writers. New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0816045771.

- Silver, Alain; Ursini, James, eds. (2007). Gangster Film Reader. Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Limelight Editions. p. 261. ISBN 9780879103323. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- Slowik, Michael (2014). After the Silents: Hollywood Film Music in the Early Sound Era, 1926–1934. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780231535502. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- Smith, Jim (2004). Gangster Films. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0753508389.

- Smyth, J.E. (2006). Reconstructing American Historical Cinema: From Cimarron to Citizen Kane. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813124063.

- Smyth, J.E. (2004). "Revisioning modern American history in the age of "Scarface" (1932)". Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television. 24 (4): 535–563. doi:10.1080/0143968042000293865. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- Springhall, John (2004). "Censoring Hollywood: Youth, moral panic and crime/gangster movies of the 1930s". The Journal of Popular Culture. 32 (3). Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- Thomas, Tony (1985). Howard Hughes in Hollywood. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press. ISBN 0806509708.

- Vasey, Ruth (1996). "Foreign Parts: Hollywood's Global Distribution and the Representative of Ethnicity". In Couvares, Francis G. Movie Censorship and American Culture. Washington & London: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1560986689.

- Warshow, Robert (March–April 1954). "Movie Chronicle: The Westerner". Partisan Review. 21 (2): 191. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Yablonsky, Lewis (1974). George Raft. McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0070722358.

- Yogerst, Chris (June 20, 2017). "Hughes, Hawks, and Hays: The Monumental Censorship Battle Over Scarface (1932)". The Journal of American Culture. 40 (2): 134–144. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

Further reading

- Cavallero, Jonathan J.; Plasketes, George (2004). "Gangsters, Fessos, Tricksters, and Sopranos: The Historical Roots of Italian American Stereotype Anxiety". Journal of Popular Film and Television. 32 (2): 50–73. doi:10.3200/JPFT.32.2.49-73. ISSN 0195-6051.

- Hagemann, E.R. (1984). "Scarface: The Art of Hollywood, Not "The Shame of a Nation"". The Journal of Popular Culture. 18 (1): 30–42. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1984.1801_30.x. ISSN 0022-3840.

- Klemens, Nadine (2006). Gangster mythology in Howard Hawks' "Scarface - Shame of the nation". GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-47698-0.

- Majumdar, Gaurav (2004). ""I Can't See": Sovereignty, Oblique Vision, and the Outlaw in Hawks's Scarface". CR: The New Centennial Review. 4 (1): 211–226. doi:10.1353/ncr.2004.0024. ISSN 1539-6630.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scarface (1932 film). |

- Scarface on IMDb

- Scarface at the TCM Movie Database

- Scarface at Rotten Tomatoes

- Scarface at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Scarface at AllMovie

- Scarface free download with Portuguese subtitles from Internet Archive