Bhai Mati Das

| Bhai Mati Das | |

|---|---|

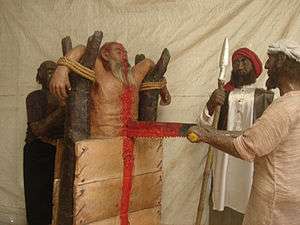

Artsistic rendering of the execution of Bhai Mati Das by the Mughals. This image is from a Sikh Ajaibghar near the towns of Mohali and Sirhind in Punjab, India | |

| Born | Karyala, in the Jhelum District (present day Pakistan) |

| Died |

1675 Chandni Chowk, Delhi, India |

| Father | Bhai Hira Nand |

| Religion | Sikhism |

Bhai Mati Das (Punjabi: ਭਾਈ ਮਤੀ ਦਾਸ; died 1675) along with his younger brother Bhai Sati Das were martyrs of early Sikh history. Bhai Mati Das, Bhai Dayala, and Bhai Sati Das were all executed at kotwali (police-station) in the Chandni Chowk area of Delhi, under the express orders of emperor Aurangzeb just before the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur. Bhai Mati Das was executed by being bound between two pillars and cut into two.[1]

Biography

Birth

Bhai Mati Das was a Brahmin of Mohyals clan[2] of the Brahmin and belonged to the Chhibber family.[3] He belonged to the ancient village of Karyala, about ten kilometres from Chakwal on the road to the Katas Raj Temple Complex, in the Jhelum District in Punjab (Pakistan). Bhai Sati Das was his younger brother and Bhai Mati Das was the son of Hira Nand, a disciple of Guru Har Gobind, under whom he had fought in many battles and was a great warrior. Hira Nand was the grandson of Lakhi Das, the son of the Bhai Praga,[4] who was also a martyr and had been a Jathedar (leader) in Guru Hargobind's first battle.[5]

Service of Guru Tegh Bahadur

During the time after Guru Har Krishan's death at Delhi and the uncertainty of the next Guru, the Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das sometimes find mention in being present looking for for [sic] the Guru[6] or directly after[7] when Baba Makhan Shah Labana found Guru Tegh Bahadur at the village of Bakala where the new Guru was then residing.

The Guru entrusted financial activity to Bhai Mati Das thus he is sometimes given the name Diwan Mati Das[8] whereas Bhai Sati Das served Guru Tegh Bahadur as a cook for the Guru.[9] The two brothers accompanied Guru Teg Bahadur during his 2-year stay at Assam.[10] Guru Tegh Bahadur bought a hillock near the village of Makhowal five miles north of Kiratpur and established a new town, Chakk Nanaki[11] now named as Anandpur Sahib (the abode of bliss) where Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das were also present.

The Guru's eastern tours

Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das were present in the Guru's eastern tours starting in August 1665 including the tours of Saifabad[12] and Dhamtan (Bangar)[13] where they were arrested perhaps because of the influence of Dhir Mal, or the Ulemas and orthodox Brahmins.[14] The Guru was sent to Delhi and detained for 1 month.[15] After being freed on December 1665 he continued his tour and Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das were again in his company particularly at Dacca, and Malda.[16]

Guru's Arrest

In 1675 the Guru was summoned by Emperor Aurangzeb to Delhi to convert to Islam.[17] Aurangzeb was very happy that all he had to do was covert one man and the rest of the Brahmins from Kashmir, Kurukshetra, Hardwar, and Beneras would follow suit.[18] The Guru left for Delhi on his own accord but was arrested at Malikpur Rangharan near Ropar.[19] While the Guru was traveling towards Delhi his company at this time consisted of his most devoted Sikhs and comprised Bhai Dayala, Bhai Udai, and Bhai Jaita (Rangretta) as well as Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das.[20] After visiting a few places where large crowds of devotees visited the Guru sent Bhai Jaita and Bhai Udai to go to Delhi so they can access the information and report it back to him and report it to Anandpur as well.[21] After being arrested Guru Tegh Bahadur was taken to Sirhind from which he was sent to Delhi in an iron cage.[22] At Delhi, the Guru and his five companions were taken into the council chamber of the Red Fort. The Guru was asked numerous questions on religion, Hinduism, Sikhism and Islam, such as why he was sacrificing his life for people that wear Janeu and Tilak when he himself was a Sikh upon which the Guru answered that the Hindus were powerless and weak against tyranny, they had come to the abode of Guru Nanak as refuge, and that with the same logic he would have sacrificed his life for Muslims as well.[23] On the Guru's emphatic refusal to abjure his faith, he was asked why he was called Teg Bahadur (gladiator or Knight of the Sword; before this, his name had been Tyag Mal). Bhai Mati Das immediately replied that the Guru had won the title by inflicting a heavy blow on the imperial forces at the young age of fourteen. Guru Tegh Bahadur was reprimanded for his breach of etiquette and outspokenness and the Guru and his companions were ordered to be imprisoned and tortured until they agreed to embrace Islam.[24]

Guru's Martyrdom

After a few days, Guru Tegh Bahadur and three of his companions were produced again before the Qazi of the city and again the Sikhs repeated their sentiments.[25] Bhai Mati Das was offered marriage of the Nawab's daughter as well as governship of the province if he converted to Islam.[26]

On November 11, 1676[27] large crowds gathered to see the Guru[28] and the executioners were called to the kotwali (police-station) near the Sunehri Masjid in the Chandni Chowk and the Guru who was kept in an iron cage[29] and all the three of his companions were moved to the place of the execution. Mughal Empire records from 17th century explain Bhai Mati Das death as punishment for challenging the authority.[30] Bhai Mati Das, Bhai Dayala and Bhai Sati Das were then tortured and executed.

Martyrdom of Bhai Mati Das

Bhai Mati Das who was the first to be martyred[31] he was asked for any final wishes which he desired to be facing towards the Guru on his execution.[32] Bhai Mati Das was made to stand erect between two posts and double headed saw[33] was placed on his head and moved across from head to the loins. While being sawed Bhai Mati Das recited the Japuji Sahib,[34] there is a mystical belief that the recitation of the Gurbani was continued and was completed even though two distinct halves of the body were made.[35] Seeing this Dyal Das abused the Emperor and his courtiers for this infernal act.[36]

Martyrdom of Bhai Dayala and Bhai Sati Das

Bhai Dayala was tied up like a round bundle and put into a huge bronze[37] cauldron of boiling oil. He was roasted alive into a block of charcoal.[38] No sign of grief was shown by the disciple of the Guru[39] and the Guru also witnessed all this savagery with divine calm.[40][41]

Bhai Sati Das was tied to a pole[42] and wrapped in cotton fibre. He was then set on fire by the executioner.[43] He remained calm and peaceful and kept uttering Waheguru Gurmantar, while fire consumed his body.

Martyrdom of the Guru

Early next morning Guru Tegh Bahadur was beheaded by an executioner called Jalal-ud-din Jallad,[44] who belonged to the town of Samana in present-day Punjab. The spot of the execution was under a banyan tree (the trunk of the tree and well near-by where he took a bath are still preserved),[45] opposite the Sunheri Masjid near the Kotwali in Chandni Chowk where he was lodged as a prisoner, on November 11, 1675.

His head was carried by Bhai Jaita,[46] a disciple of the Guru, to Anandpur where the nine-year-old Guru Gobind Singh cremated it(The gurdwara at this spot is also called Gurdwara Sis Ganj Sahib). The body, before it could be quartered, was stolen under the cover of darkness by Lakhi Shah Vanjara, another disciple who carried it in a cart of hay and cremated it by burning his hut, at this spot, the Gurdwara Rakab Ganj Sahib stands today.[47] Later on, the Gurdwara Sis Ganj Sahib, was built at Chandni Chowk at the site of Guru’s martyrdom.

Legacy

Bhai Mati Das is regarded as a great martyr by the Sikh.[48] The date of his martyrdom, is celebrated in certain parts of South Asia as a public holiday.[37][38][39] Bhai Mati Das' martydom finds explicit mention[49] in the daily supplication prayers of Ardas.

The Bhai Mati Das Sati Das Museum was built in honor of Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das in Delhi opposite Gurudwara Sis Ganj Sahib, Chandni Chowk the spot where they were martyred.[50][51]

See also

References

- ↑ Singh, Harjinder (2011). Game of Love (Second ed.). Walsall: Akaal Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 9780955458712.

- ↑ Agrawal, Lion M. G. (200 8). Freedom Fighters of India. Delhi: Gyan Publishing House. p. 87. ISBN 9788182054707. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Singh, Bakhshish (1998). Proceedings: Ed. Parm Bakhshish Singh, Volume 1 Punjab History Conference. Patiala: Publ. Bureau, Punjabi Univ. p. 113. ISBN 9788173804625.

- ↑ Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1606-1708 C.E. Atlantic Publishers. p. 593. ISBN 9788126908585.

- ↑ http://www.sikh-history.com/sikhhist/martyrs/satidass.html

- ↑ Kohli, Mohindar (1992). Guru Tegh Bahadur: Testimony of Conscience. Sahitya Akademi. p. 14. ISBN 9788172012342.

- ↑ Singh, Prithi Pal (2006). The History of Sikh Gurus. New Delhi: Lotus Press. p. 116. ISBN 9788183820752.

- ↑ Stracey, Rusell (1911). The History of the Muhiyals: The Militant Brahman Race of India. p. 24.

- ↑ Singh, Harbans (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism: S-Z. Patiala: Publications Bureau. p. 76. ISBN 9788173805301.

- ↑ Gupta, Hari (1984). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 375. ISBN 9788121502764.

- ↑ Singh, Harbans. Guru Tegh Bahadur. Sterling Publishers. p. 98.

- ↑ Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold Volume II: 1606-1708 C.E. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors,. p. 629. ISBN 9788126908585.

- ↑ Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold Volume II: 1606-1708 C.E. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors,. p. 630. ISBN 9788126908585.

- ↑ Singh, Fauja; Talib, Gurbachan (1975). Guru Tegh Bahadur: Martyr and Teacher. Patiala: Punjabi University. p. 44.

- ↑ Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold Volume II: 1606-1708 C.E. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors,. p. 631. ISBN 9788126908585.

- ↑ Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold Volume II: 1606-1708 C.E. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors,. p. 632. ISBN 9788126908585.

- ↑ Singh, Hari (1994). Sikh Heritage, Gurdwaras & Memorials in Pakistan. Asian Publication Services. p. 80.

- ↑ Singh, Trilochan (1967). Guru Tegh Bahadur Prophet and Martyr (A Biography). Sis Ganj, Chandni Chowk, Delhi: Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Parbhandak Committee. p. 376.

- ↑ Singh, Patwant (2007). The Sikhs. Crown Publishing G. ISBN 9780307429339.

- ↑ Singh, Iqbal (2014). Sikh Faith - An Epitome of Inter-Faith for Divine Realisation (Second ed.). Sant Attar Singh Hari Sadhu Ashram: Kalgidhar Trust. p. 384.

- ↑ Singh, Iqbal (2014). Sikh Faith - An Epitome of Inter-Faith for Divine Realisation (Second ed.). Sant Attar Singh Hari Sadhu Ashram: Kalgidhar Trust. p. 384.

- ↑ Singh, Patwant (2007). The Sikhs. Crown Publishing G. ISBN 9780307429339.

- ↑ Singh, Iqbal (2014). Sikh Faith - An Epitome of Inter-Faith for Divine Realisation (Second ed.). Sant Attar Singh Hari Sadhu Ashram: Kalgidhar Trust. p. 384.

- ↑ Venkatesvararavu, Adiraju (1991). Sikhs and India: Identity crisis. Sri Satya Publications. p. 36.

- ↑ Singh, Gurpreet (2017). Ten Masters. Diamond Pocket Books Pvt Ltd.

- ↑ Singh, Gurpreet (2005). Soul of Sikhism. Delhi: Fusion Books. p. 100. ISBN 9788128800856.

- ↑ Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold Volume II: 1606-1708 C.E. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors,. p. 664. ISBN 9788126908585.

- ↑ Gill, Pritam (1975). Guru Tegh Bahadur, The Unique Martyr. New Academic Pub. Co. p. 69.

- ↑ Surinder, Johar (1975). Guru Tegh Bahadur: A Bibliography. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 206. ISBN 9788170170303.

- ↑ "The Hindu: Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom". thehindu.com. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ Arneja, Simran (2009). 'Ik Onkar One God'. p. 45. ISBN 9788184650938.

- ↑ Singh, Gurpreet (2005). Soul of Sikhism. Delhi: Fusion Books. p. 100. ISBN 9788128800856.

- ↑ Gupta, Hari (1978). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 376.

- ↑ Singh, Gurpreet (2005). Soul of Sikhism. Delhi: Fusion Books. p. 100. ISBN 9788128800856.

- ↑ Singh, Harjinder (2011). Game of Love (Second ed.). Walsall: Akaal Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 9780955458712.

- ↑ Singh, H. S. (2005). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (Second ed.). New Delhi: Hemkunt Press. p. 56. ISBN 8170103010.

- ↑ Singh, Gurpreet (2005). Soul of Sikhism. Delhi: Fusion Books. p. 100. ISBN 9788128800856.

- ↑ Singh, H. S. (2005). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (Second ed.). New Delhi: Hemkunt Press. p. 56. ISBN 8170103010.

- ↑ Singh, Harjinder (2011). Game of Love (Second ed.). Walsall: Akaal Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 9780955458712.

- ↑ Gupta, Hari (1978). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 376.

- ↑ Duggal, Kartar (1980). The Sikh Gurus: Their Lives and Teachings. Vikas. p. 176. ISBN 9780706909951.

- ↑ Singh, Prithi Pal (2006). The History of Sikh Gurus. New Delhi: Lotus Press. p. 124. ISBN 9788183820752.

- ↑ Corduan, Winfried (2013). Neighboring Faiths: A Christian Introduction to World Religions. InterVarsity Press. p. 383. ISBN 9780830871971.

- ↑ Ralhan, O. P. (1997). The Great Gurus of the Sikhs: Banda Bahadur, Asht Ratnas etc. Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 9788174884794.

- ↑ Sahi, Joginder (1978). Sikh Shrines in India & Abroad. Common World. p. 60.

- ↑ Singh, H. S. (2005). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (Second ed.). New Delhi: Hemkunt Press. p. 187. ISBN 8170103010.

- ↑ Das, Madan (2014). Story Of Harry Singh & Sophie Kaur. Partridge India. p. 168. ISBN 9781482821352.

- ↑ "Bhai Mati Das Ji profile". searchsikhism.com. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ Singh, Inder Pal (1999). The Grandeur of Khalsa. Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University. p. 77.

- ↑ Kindersley, Dorling (2010). Top 10 Delhi (First ed.). New York: Penguin. p. 10. ISBN 9780756688493.

- ↑ Fodor's Essential India: with Delhi, Rajasthan, Mumbai & Kerala. Fodor's Travel. 2015. ISBN 9781101878682.

Sources

- Bhai Mati Das Ji, searchsikhism.com; accessed 12 November 2016.

- Kartar Singh, Sikh History Book 5, Hemkunt Press, New Delhi, India