Beit HaShita

| Beit HaShita | |

|---|---|

Beit HaShita | |

Beit HaShita | |

| Coordinates: 32°33′15″N 35°26′15″E / 32.55417°N 35.43750°ECoordinates: 32°33′15″N 35°26′15″E / 32.55417°N 35.43750°E | |

| District | Northern |

| Council | Gilboa |

| Affiliation | Kibbutz Movement |

| Founded | 12 December 1935[1] |

| Founded by | Kvutzat HaHugim/Tnuat HaMahanot HaOlim members |

| Population (2017)[2] | 1,251 |

| Website | www.beithashita.org.il |

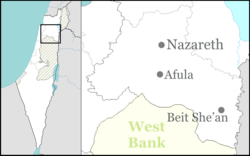

Beit HaShita (Hebrew: בֵּית הַשִּׁטָּה, lit. House of the Acacia) is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located between Afula and Beit She'an, it falls under the jurisdiction of Gilboa Regional Council. In 2017 it had a population of 1,251.[2]

Geography

The built-up area of Beit Hashita ranges from sea level to 70 meters below.[3]

History

Ottoman era

During the Ottoman era, a village named Shutta was located at the site of the kibbutz.[4] It has been suggested that Shutta was marked on the map Pierre Jacotin compiled in 1799, misnamed as Naim.[5]

While travelling in the region in 1838, Edward Robinson noted Shutta as a village in the general area of Tamra,[6] while during his travels in 1852 he noted it as being a village north of the Jalud.[7]

When Victor Guérin visited in 1870, he found here "a good many silos cut in the ground and serving as underground granaries to the families of the village", and "The women have to go for water to the canal of ´Ain Jalud - marked on the map as the Wady Jalud."[8]

In 1881, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Shutta as a small adobe village on rising ground, surrounded by hedges of prickly pear and plough-land.[9]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, Shutta had a population of 280; 277 Muslims and 3 Orthodox Christians,[10][11] decreasing in the 1931 census to 255; 2 Jews, 3 Christians and 250 Muslims, in a total of 85 houses.[12]

The kibbutz traces its origin to a group meeting held in Hadera in 1928, by "Kvuzat HaHugim" of the HaMahanot HaOlim movement from Haifa and Jerusalem.[13] The first members lived at nearby Ein Harod until 1934, when establishment of the kibbutz began at its present location about 1 km east of the village of Shatta.[13]

The land of the kibbutz, part of the village land of Shutta including the village itself, was purchased by the Palestine Land Development Company from its Arab owners in 1931.[14][15] The tenants contested the purchase, claiming to be the rightful owners, but the Beisan Civil Court ruled against them.[14] The fate of the tenants and workers, numbering more than 200, became a matter of dispute between the government, the sellers, and the buyers.[14] The Jewish Agency maintained that the terms of sale were for the land to be delivered free of residents, while the main seller Raja Ra'is apparently made use of loopholes in the law to provide the tenants with compensation below that to which they were entitled.[14] The case led to a 1932 amendment of the law to better protect evicted tenants.[14] In 2015, a grandchild of kibbutz residents, Jasmine Donahaye, published a book "Losing Israel" in which she expressed her disillusionment on learning of the eviction of Arabs on the founding of the kibbutz.[16]

The kibbutz was later named after the biblical town Beit Hashita, where the Midianites fled after being beaten by Gideon (Judges 7:22),[17][18] thought to be located where Shatta was. It falls under the jurisdiction of Gilboa Regional Council.

In the 1945 statistics, Beit hash Shitta had 590 inhabitants, all Jews. It was noted that Shatta was an alternative name.[19][20]

Post-1948

In 1948, Beit HaShita took over 5,400 dunams of land from the newly depopulated Arab villages of Yubla and Al-Murassas.[21]

Eleven kibbutz members fell during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the largest number as a percentage of the population than any other town in Israel.[22]

Economy

Beit Hashita produced cotton, wheat, melons, olives and citrus fruits. There was also a dairy barn, chickens and a fish farm. In the 1960s, Beit HaShita established a pickling factory which produces and markets pickles, olives and pickled vegetables under the brand name Beit HaShita.[23] The factory also produces syrups for making juices under the brand name Vitaminchick. The factory was bought from the kibbutz in 1998 by the Israeli food manufacturer, Osem.[24]

Religion and culture

The Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture, an organization that preserves the cultural heritage of the kibbutz, was established by kibbutz member Aryeh Ben-Gurion, nephew of Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion.[25] Beit Hashita served as the basis for the 1981 English language book Kibbutz Makom, which described the kibbutz society.[26] Many of the member families of the kibbutz are secular. There is however a small orthodox synagogue.

Archaeology

Ceramics and coins from the Byzantine era were found in the region of Beit Hashita.[27]

Notable residents

References

- ↑ State of Israel (1952) Supplement page III

- 1 2 "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Survey of Israel, Topographic map

- ↑ The name probably derives from "a river bank", according to Palmer, 1881, p. 167

- ↑ Karmon, 1960, p. 169

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 219

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1856, p. 339

- ↑ Guérin, 1874, pp. 301-302; as given in Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 126

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 86

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table IX, p. 31

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XV, p. 48

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 80

- 1 2 "Historical summary on kibbutz website".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stein, 1984, pp. 125,134,263–264.

- ↑ Kark, 1997

- ↑ Nathan Abrams, A Disillusioned Zionist's Bird’s-eye View of Israel, Haaretz, 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Carta's Official Guide to Israel and Complete Gazetteer to all Sites in the Holy Land. (3rd edition 1993) Jerusalem, Carta, p.110 , ISBN 965-220-186-3 (English)

- ↑ Yizhaqi, Arie (ed.): Madrich Israel (Israel Guide: An Encyclopedia for the Study of the Land), Vol.8: The Northern Valleys, Samaria and Mount Carmel, Jerusalem 1980, Keter Press, p.401 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 6

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 43

- ↑ Fischbach, 2012, p. 13

- ↑ A Yom Kippur melody spun from grief, atonement and memory Times of Israel, 25 September 2012

- ↑ Scattered Tribe: Traveling the Diaspora from Cuba to India to Tahiti & Beyond, Ben Frank

- ↑ "Beit Hashita | Factories Osem". Osem. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- ↑ Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture

- ↑ Michal Palgi & Shulamit Reinharz (2014) One Hundred Years of Kibbutz Life: A Century of Crises and Reinvention, Transaction Publishers, 31 Jan 2014, p123

- ↑ Dauphin, 1998, p. 776

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0860549054.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Donahaye, Jasmine (2015). Losing Israel. Seren Books. ISBN 1781722528.

- Fischbach, Michael R. (2012). Records of dispossession: Palestinian refugee property and the Arab–Israeli conflict (Illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12978-7.

- Guérin, V. (1874). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Kark, Ruth (1997). "Mamlūk and Ottoman Cadastral Surveys and Early Mapping of Landed Properties in Palestine". Agricultural History. 71 (1): 46–70.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Hadawi, Sami (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Lieblich, A. (1981). Kibbutz Makom: Report From an Israeli kibbutz. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-50724-X.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- State of Israel (1952). Government Year-book (English ed.).

- Stein, K. (1984). The Land Question in Palestine. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4178-5.

External links

- Official website

- Survey of Western Palestine, map 9: IAA, Wikimedia commons