Battle of San Carlos (1982)

The Battle of San Carlos was a major battle between aircraft and ships that lasted from 21 to 25 May 1982 during the British landings on the shores of San Carlos Water (which became known as "Bomb Alley"[2][3]) in the 1982 Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas). Low-flying land-based Argentine jet aircraft made repeated attacks on ships of the British Task Force.

It was the first time in history that a modern surface fleet armed with surface-to-air missiles and with air cover backed up by STOVL carrier-based aircraft defended against full-scale air strikes. The British sustained severe losses and damage, but were able to create and consolidate a beachhead and land troops.

Background

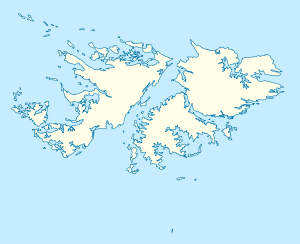

After the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands the United Kingdom initiated Operation Corporate, sending a Task Force 12000 km south in order to retake the islands. Under the codename Operation Sutton the British forces planned amphibious landings around San Carlos, on an inlet located off Falkland Sound, the strait between East Falkland and West Falkland. The location was chosen as the landing force would be protected by the terrain against Exocet and submarine attacks, and it was distant enough from Stanley to prevent a rapid reaction from Argentine ground troops stationed there.[4]

The landing took the Argentines completely by surprise; Argentine Navy officers had considered that the location was not a good choice for such an operation, and had left the zone without major defences.[5]

Argentine aircraft

Argentine forces operated under range and payload limitations as they had limited refuelling resources and were operating at maximum range.

- A-4 Skyhawk: The A-4 was used by both the Argentine Air Force (FAA) and Argentine Naval Aviation (COAN). In spite of using two 295-gallons drop tanks, they needed aerial refuelling twice during missions. Bomb load used during the conflict was one British-made 1000 lb (Mk 17) unguided bomb or four 227 kg Spanish/American built retarding tail bombs. The aircraft were armed with two 20 mm Colt Mk 12 cannon.

- IAI Dagger: The Israeli-built Mirage 5 did not have aerial refuelling capacity, and even using two 550-gallon drop tanks to carry extra fuel, they were flying at the absolute limit of their range. Their main weapon during the conflict was the British-made 1000 lb (Mk 17) unguided bomb. They retained their 30 mm DEFA cannon.

- Mirage IIIEA: The French-built interceptor has an internal fuel tank smaller than that of the Dagger, so they could not fly low enough to escort the strike aircraft. They carried a pair of R550 Magic IR missiles in their high-altitude flights to the islands, but the British Harrier combat air patrols concentrated on the low-flying bombers.

- FMA IA-58 Pucara: The Argentine-built counter-insurgency aircraft operated from the Goose Green grass airstrip during the battle. The aircraft were armed with rocket pods, two 20 mm cannons, and four 7.62 mm machine guns.

British amphibious force

British air cover was provided for the first time by "Harrier carriers". These carriers deployed short-takeoff, vertical-landing Harriers.

- Air Cover:

- Aircraft carrier HMS Hermes (R12)

- 800 Squadron (BAE Sea Harrier)

- 809 Squadron (BAE Sea Harrier)

- Aircraft carrier HMS Invincible (R05)

- 801 Squadron (BAE Sea Harrier)

- 809 Squadron (BAE Sea Harrier)

- Aircraft carrier HMS Hermes (R12)

- Landing force: HMS Fearless, HMS Intrepid, RFA Sir Geraint, RFA Sir Tristram, RFA Sir Galahad, RFA Sir Percivale, RFA Sir Lancelot, SS Canberra, RFA Fort Austin, Europic Ferry 4 and Elk 5.

- Escort force: HMS Antrim, HMS Coventry, HMS Broadsword, HMS Brilliant, HMS Ardent, HMS Antelope, HMS Argonaut, HMS Plymouth and HMS Yarmouth

Engagements

Due to the distance required to fly to the islands, two minutes was the average time Argentine attack aircraft had available in the target area.

This is a list of the main sorties carried out by Argentine air units showing approximate local time, Aircraft and Call signal.

21 May

The Argentine Army force on site was a section from the 25th Infantry Regiment named Combat team Güemes (Spanish: Equipo de Combate Güemes) located at Fanning Head. The British fleet entered San Carlos during the night and at 02:50 was spotted by EC Güemes which opened fire with 81mm mortars and two recoilless 105mm rifles. They were soon engaged by British naval gunfire and a 25-man SBS team and forced to retreat, losing their communications equipment but shooting down two Gazelle helicopters with small-arms fire, killing three members of the two aircrews.

1st Lt Carlos Daniel Esteban from EC Güemes informed Goose Green garrison about the landings at 08:22 (he was finally evacuated by helicopter on 26 May). The Argentine high command at Stanley initially thought that a landing operation was not feasible at San Carlos and the operation was a diversion. At 10:00, a COAN Aermacchi MB-339 jet based on the islands was dispatched to San Carlos on a reconnaissance flight. In the meantime, the FAA had already started launching their mainland-based aircraft at 09:00.

Between 10:15 and 17:12 seventeen sorties were carred out by FAA and COAN. Dagger and A-4C of the FAA made attacks on HMS Antrim, HMS Argonaut, HMS Broadsword, HMS Brilliant, HMS Ardent, HMS Brilliant. Sorties of MIIIEA aircraft were used as diversions as-well. While many of the bombs did not explode, HMS Ardent and HMS Argonaut were hit, sustaining damage and casualties. Sea Harriers intercepted some of the attackers, destroying 8 FAA aircraft.

22 May

Bad weather over the Patagonia airfields prevented the Argentines from carrying out most of their air missions; only a few Skyhawks managed to reach the islands. The British completed their surface-to-air Rapier battery launcher deployments.

23 May

On 23 May Argentine aircraft resumed attacking, striking HMS Antelope, HMS Broadsword, HMS Yarmouth, and HMS Antelope. Only HMS Antelope was damaged, sinking after an unexploded bomb detonated while being defused. Of the attacking aircraft, two were shot down. An additional COAN pilot was killed after ejecting from his A-4Q after a tyre burst upon landing.

24 May

On 24 May the Argentine pilots on the continent openly expressed their concern about the lack of collaboration between the three branches of the armed forces, and protested with passive resistance. General Galtieri, acting president of Argentina, decided to visit Comodoro Rivadavia the next day, 25 May (Argentina's National Day), to try to convince them to keep fighting, but when he arrived in the morning the pilots had changed their minds and were already flying to the islands.[7]

Six sorties were launched by the FAA against the British forces. RFA Sir Lancelot and probably Sir Galahad and Sir Bedivere and ground targets were attacked. Four attack aircraft were shot down, with one pilot killed.

25 May

Attacks by the FAA on 25 May proved more successful than the previous day. HMS Coventry was sunk after being hit with 500 lb (230 kg) bombs. Attacks on HMS Broadsword damaged the frigate's communication systems and hydraulics and shattered the nose of her Sea Lynx helicopter. RFA Sir Lancelot was also attacked. One sortie accidentally attacked Goose Green, mistaking it for Ajax bay, and were hit by small arms friendly fire. Three attackers were shot down; one by a Rapier Missile from 'T' Battery of 12 Regiment Royal Artillery, and two by Sea Dart fired by HMS Coventry.

| List of Sorties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Branch | Aircraft | Callsign | Pilot(s) | Summary |

| 21 May | |||||

| 10:15 | COAN | MB339 | 4-A-115 | Lt Guillermo Owen Crippa | A reconnaissance flight flew over the landing force twice to determine the exact composition of the fleet, earning the highest national military decoration, the Argentine Nation to the Heroic Valour in Combat Cross. He attacked HMS Argonaut and an unidentified RFA ship with guns and rockets, then withdrew. |

| 10:15 | FAA | Pucara | Tigre | Cpt Benítez Mj Tomba 1st Lt Micheloud | Three (of four) planes scrambled from Goose Green and were engaged by gunfire from HMS Ardent. Cpt Benítez was shot down by a Stinger missile fired by the Special Air Service; he ejected and walked back to his base, arriving at 19:00. The other two pilots, Mj Tomba and 1st Lt Micheloud, fired 2.75-inch rockets at a shed apparently used by British forces as an observation post, but were intercepted by two Sea Harriers during their escape. Mj Tomba was shot down (ejecting safely) by pilot Nigel Ward,[8] while Lt Micheloud's aircraft escaped and landed at Port Stanley's airfield. |

| 10:20 | FAA | MIIIEA | Four aircraft made a diversion north of the islands. | ||

| 10:25 | FAA | Dagger | Leon | Cpt Dimeglio Lt Castillo | From San Julian, Cpt Dimeglio and Lt Castillo attacked HMS Antrim with their 30mm cannon. Their 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs failed to explode. |

| 10:30 | FAA | Dagger | Ñandú | Cpt Rodhe Lt Bean | From Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego, Cpt Rodhe and Lt Bean attacked HMS Argonaut, Lt Bean was shot down by a Sea Wolf SAM from HMS Broadsword; Broadsword was attacked by pilot Cpt Janet. |

| 10:35 | FAA | Dagger | Zorro | Cpt Dellepine Cpt Diaz Cpt Aguirre-Faget | Cpt Dellepine, Cpt Diaz and Cpt Aguirre-Faget bombed and strafed HMS Brilliant but the bombs hang-up. |

| 10:50 | FAA | Dagger | Perro | Mj Martinez Cpt Moreno Lt Volponi | Mj Martinez, Cpt Moreno and Lt Volponi attacked HMS Antrim. Their 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs did not explode, but one of them hit the stern of the destroyer, which also received damage from 30 mm strafing. During their escape, Sea Harriers launched Sidewinders against the Daggers but the missiles fell short. |

| 12:45 | FAA | A-4C | Pato | Cpt Almoño Cpt Garcia 1st Lt Daniel Manzotti Lt Nestor Lopez | Intercepted by Sea Harriers; Manzotti and López were shot down and killed by Sidewinders. |

| 12:45 | FAA | A-4B | Mula | Cpt Carballo Ensign Carmona | Mula 2 attacked an unknown ship, most probably the abandoned Argentine cargo vessel Rio Carcaraña, and withdrew,[9] Carballo continued alone and attacked HMS Ardent straddling her with two bombs, both of which failed to explode.[10] |

| 13:37 | FAA | A-4B | Leo | 1st Lt Filippini Lt Autiero Lt Osses Lt Robledo Ensign Vottero | Hit HMS Argonaut with 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs which did not explode, with one crashing through her Sea Cat magazine, detonating two missiles and causing damage and two fatalities among Argonaut's crew. |

| 14:30 | FAA | MIIIEA | Two aircraft took off as a diversion. | ||

| 14:35 | FAA | Dagger | Cueca | Cpt Mir Gonzales Cpt Robles 1st Lt Luna Lt Bernhard. | Intercepted by Sea Harriers, and Lt Luna was hit by a Sidewinder but ejected safely. The other three pilots attacked HMS Ardent, and hit the warship with 30 mm gunfire and two 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs on her stern before returning safely to their base. The frigate's Sea Lynx helicopter was destroyed. |

| 14:53 | FAA | Dagger | Laucha | Mj Puga 1st Lt Román | Attacked HMS Brilliant. The third pilot attacked an unknown ship, probably HMS Antrim. |

| 14:58 | FAA | Dagger | Raton | Mj Piuma Cpt Donadille 1st lt Senn. | Intercepted by Sea Harriers of Nigel Ward and Lt Thomas. The Daggers dropped their ordnance −2 fuel tanks and one 1,000 lb (450 kg)- and tried to escape, but the three were shot down by Sidewinders, with all pilots ejecting safely. After recovering the pilots, the FAA realised that the San Julian-based Daggers' approach corridor had been discovered and made efforts to correct the situation. |

| 15:15 | COAN | A-4Q | Tabanos | Cpt Philipi Lt Arca Lt Marquez | Hit HMS Ardent with several 500 lb (230 kg) retarding tail bombs and cannon fire. Two aircraft were shot down by Sea Harriers during their escape, killing Lt Marcelo Márquez. Lt. Philippi ejected safely and, after being sheltered by local farmer Tony Blake during the night,[11] he rejoined the Argentine forces. The third A-4Q, Lt Arca, was damaged and the pilot bailed out into the sea approximately 800 to 1,000 meters off Cape Pembroke, Port Stanley. Arca was rescued from the water by Capt. Jorge “Picho” Svendsen's Huey UH-1H from the Army's 601 Helicopter Battalion. HMS Ardent sank. Both crew were decorated with the Valour in Combat Medal. |

| 17:02 | FAA | A-4C | No ships found. | ||

| 17:12 | FAA | A-4B | No ships found. | ||

| 23 May | |||||

| 13:30 | FAA | A-4B | Nene | Carballo 1st Lt Guadagnini Lt Rinke Ensign Gomez | Attacked HMS Broadsword and HMS Antelope. Carballo's plane was damaged by a Sea Cat missile, fired from Antelope, during his bombing run, so he broke off the attack and returned to Rio Gallegos. A second Argentine plane dropped a 1,000 lb (450 kg) bomb on Antelopes starboard side, killing Crewman Mark R. Stephens. Lieutenant Guadagnini was hit and killed by HMS Antelope's 20mm cannon and crashed through her main mast while carrying out his bombing run; his bombs pierced the frigate's hull without exploding.[12] After the attack, one of these detonated while being defused, sinking the ship. |

| 13:45 | COAN | A-4Q | Tabanos | Cpt Castro Fox Cpt Zubizarreta Lt Benitez | Attacked HMS Broadsword, HMS Yarmouth and HMS Antelope without visible success. Cpt Carlos María Zubizarreta was killed in Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego when his parachute did not fully open after he ejected from his A-4Q due to a tyre bursting on landing with his bombs still loaded. The plane stopped by itself and did not suffer any damage.[13][14] |

| 15:10 | FAA | Dagger | Puñal | Mj Martinez Lt Volponi | Intercepted by Sea Harriers, which shot down the second aircraft, whilst Martinez returned to base. |

| 15:10 | FAA | Dagger | Daga | Struck targets inside Ajax Bay | |

| 15:10 | FAA | Dagger | Coral | Struck targets inside Ajax Bay | |

| 24 May | |||||

| 10:15 | FAA | A-4B | Chispa Nene | Com Mariel 1st Lt Sanchez Lt Roca Lt Cervera Ensign Moroni | Attacked ships inside the bay. RFA Sir Lancelot was hit by a 1,000 lb (450 kg) bomb, which did not explode. Two LCUs are also attacked. |

| 11:02 | FAA | Dagger | Azul | Cpt Mir Gonzalez Cpt Maffeis Cpt Robles Lt Bernhardt | Attacked unidentified ships, probably RFA Sir Bedivere, inside the bay. |

| 11:07 | FAA | Dagger | Plata | Cpt Dellepiane 1st Lt Musso Lt Callejo | Struck ground targets with 500 lb (230 kg) retarding tail bombs. |

| 11:08 | FAA | Dagger | Oro | Mj Puga Cpt Diaz 1st Lt Castillo | Intercepted and shot down by Sea Harriers. Castillo was killed and the other two ejected safely. |

| 11:20 | FAA | A-4C | Halcon | Cpt Pierini 1st Lt Ureta Lt Mendez | Intercepted by Sea Harriers but managed to return to base. |

| 11:30 | FAA | A-4C | Jaguar | 1st Lt Vazquez Lt Bono Ensign Martinez | Attacked unidentified ships, possibly RFA Sir Galahad, inside the bay. The three aircraft all received battle damage with Bono's aircraft crashing during the return flight. The other two Skyhawks were rescued by a KC-130 tanker, which approached the islands and delivered 30,000 litres of fuel while accompanying them to the airfield at San Julian. |

| 25 May | |||||

| 09:00 | FAA | A-4B | Marte | Cpt Hugo Palaver Lt Daniel Gálvez | Cpt Hugo Palaver's aircraft was damaged in a friendly fire incident when he and Lt Daniel Gálvez accidentally flew over Goose Green and strafed the pier there, in the belief that they were over Ajax Bay.[15] The main anti-aircraft artillery identified the fighters as friendly and did not fire, but soldiers on the ground engaged with small arms fire.[16] When they returned to the strait, Palaver was shot down by a Sea Dart missile fired by HMS Coventry |

| 12:25 | FAA | A-4C | Toro | Cpt Garcia Lt Lucero Lt Paredi Ensign Issac | Attacked ships inside the bay, probably RFA Sir Lancelot. After the attack Lucero was shot down by a Rapier Missile, from 'T' Battery of 12 Regiment Royal Artillery. He successfully ejected over the landing force,[17] was rescued and then transferred to the hospital ship SS Uganda. A Sea Dart, fired by HMS Coventry, shot down Garcia, whose aircraft had been damaged by small arms fire during the attack, to the North of San Carlos. Cpt Garcia ejected, but was not recovered and died. Ensign Isaac was losing fuel but was rescued by the KC-130, which accompanied him to his base while refuelling him in flight. |

| 15:20 | FAA | A-4B | Vulcano | Cpt Carballo Lt Carlos Rinke | Attacked HMS Broadsword,picture from shipdamaging the frigate's communication systems and hydraulics and electrics[18] and shattering the nose of her Sea Lynx helicopter Pictures of the Damage |

| 15:20 | FAA | A-4B | Zeus | 1st Lt Velasco Ensign Barrionuevo | Attacked and sank destroyer HMS Coventry after hitting the ship with three 500 lb (230 kg) bombs.British video Argentine video |

Aftermath

I think the Argentine pilots are showing great bravery, it would be foolish of me to say anything else

In spite of the British air defence network, the Argentine pilots were able to attack their targets but some serious procedural failures prevented them from getting better results – most notably problems with their bombs' fuses. Thirteen bombs[20] hit British ships without detonating. Lord Craig, the retired Marshal of the Royal Air Force, is said to have remarked: "Six better fuses and we would have lost".[21]

The British warships, although themselves suffering most of the attacks, were successful in keeping the strike aircraft away from the landing ships, which were well inside the bay.[22] With the British troops on Falklands soil, a land campaign followed until Argentine General Mario Menéndez surrendered to British Major General Jeremy Moore on 14 June in Stanley.

The subsonic Harrier jump-jet, armed with the most advanced variant of the Sidewinder air-to-air missile, proved capable as an air superiority fighter.

The actions had a profound impact on later naval practice. During the 1980s most warships from navies around the world were retrofitted with close-in weapon systems and guns for self-defence. First reports of the number of Argentine aircraft shot down by British missile systems were subsequently revised down.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ [9 Dagger, 5 A-4C, 3 A-4Q, 3 A-4B & 2 Pucara]

- ↑ Yates, David (2006). Bomb Alley – Falkland Islands 1982. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-417-3.

- ↑ "Americas | Charles ends Falklands tour on sombre note". BBC News. 15 March 1999. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ "Julian Thompson interview". clarin. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ Commodore Ruben Oscar Moro: La Guerra Inaudita, ISBN 987-96007-3-8, ... consideraban que el desembarco Britanico no podia ser alli ... debido a un concepto naval que asociaba la capacidad de una flota con su espacio de maniobra para un desembarco ...

- ↑ "Argentine Airpower in the Falklands War: An Operational View". Airpower.maxwell.af.mil. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ Costa, Eduardo José (1988). Guerra Bajo la Cruz del Sur. Hyspamérica, p. 334. ISBN 950-614-749-3 (in Spanish)

- ↑ "Major Carlos Tomba's Pucara". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ↑ Some sources identify this ship as the Rio Carcaraña but other sources place the cargo vessel in Bahía Rey ( King George Bay ? ) at the time

- ↑ "Board of Inquiry – Report into the Loss of HMS Ardent, page 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ La balada del piloto bahiense y el estanciero kelper (in Spanish)

- ↑ "Primer Teniente Guadagnini". Google. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "''3ra. Escuadrilla Aeronaval de Caza y Ataque''". Institutoaeronaval.org. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "Carlos Zubizarreta". Archived from the original on 17 December 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ Official site of the Argentine Air Force: Fuerza Aérez Argentina – Martes 25 de Mayo Archived 4 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine. (in Spanish)

- ↑ Piaggi, Italo A. (1986). Ganso Verde. Ed. Planeta, p. 83. ISBN 950-37-0186-4. (in Spanish)

- ↑ "Cpt Tomas Lucero interview". Youtube. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "HMS Broadsword damage control". Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "Google". Los Angeles Times. May 27, 1982. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "British Ships Sunk and Damaged – Falklands War 1982". Naval-history.net. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Gethin Chamberlain (5 April 2002). "Would British forces be able to retake the Falklands today?". The Scotsman. p. 12. Archived from the original on 5 April 2002. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Pablo Carballo: Halcones sobre Malvinas

- ↑ Of 14 kills and 6 probables, only one Argentine aircraft was shot down by Rapier, as originally noted by Ethell and Price. Similar discrepancies arose over other weapons systems, notably Blowpipe (one confirmed kill as against nine confirmed and two probables in the White Paper) and Sea Cat (zero to one against eight confirmed and two probables in the White Paper). FREEDMAN, Sir Lawrence, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign (Abingdon, 2005). Volume II, page 732-735

References

External links

- Interview Video on HMS Ardent attack

- Bomb Alley video – Lt Tomas Lucero rescued by HMS Fearless

- Painting of Lt Owen Crippa solo attack on the frigate "Argonaut"

.png)