Autonomous Region of Bougainville

| Autonomous Region of Bougainville | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

.svg.png) Bougainville Province in Papua New Guinea | ||

| Coordinates: 6°0′S 155°0′E / 6.000°S 155.000°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Capital | Arawa | |

| Districts | ||

| Government | ||

| • President | John Momis (2010–present) | |

| • Vice-President | Raymond Masono (2017–present) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 9,384 km2 (3,623 sq mi) | |

| Population (2011 census) | ||

| • Total | 249,358 | |

| • Density | 27/km2 (69/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC+11 (Bougainville Standard Time) | |

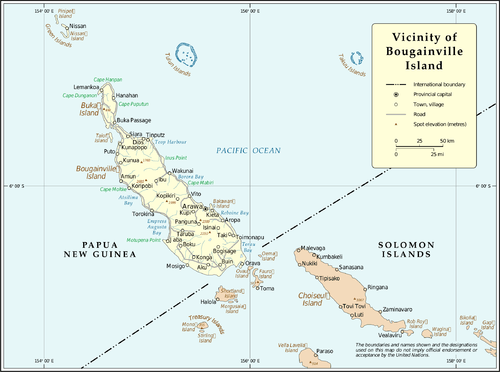

The Autonomous Region of Bougainville (/ˈboʊɡənˌvɪl/ BOH-gən-VIL), previously known as the North Solomons Province, is an autonomous region in Papua New Guinea. The largest island is Bougainville Island (also the largest of the Solomon Islands archipelago). The province also includes Buka Island and assorted outlying nearby islands including the Carterets. The capital is temporarily Buka, though it is expected that Arawa will be the permanent provincial capital. The population of the province is 249,358 (2011 census).

Bougainville Island is ecologically and geographically part of the Solomon Islands archipelago but is not politically part of the nation of Solomon Islands. Buka, Bougainville, and most of the Solomons are part of the Solomon Islands rain forests ecoregion. The region's biodiversity is heavily threatened by mining activities, mostly conducted by foreign investors.[1]

History

The island was named after the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville, who made expeditions to the Pacific. He is also the namesake of the tropical flowering vines of the genus Bougainvillea. In 1885, the island was taken over by a German administration as part of German New Guinea. Australia occupied it in 1914 during World War I. After the war the League of Nations designated it as a mandatory power and administered the island from 1918 until the Japanese invaded it in 1942 during World War II.

Australia took over administration of the island when that war ended in 1945, managing it until Papua New Guinea independence in 1975. Bougainville was appointed as a United Nations mandatory power, Australia having accepted dominion sovereignty under the Statute of Westminster 1931 in the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 and therefore being formally empowered to do so. It administered British and German New Guinea, but was not the official colonial power.

During World War II, the island was occupied by Australian, American and Japanese forces. It was an important base for the RAAF, RNZAF and USAAF. On 8 March 1944, during the Pacific War, American forces were attacked by Japanese troops on Hill 700 on this island. The battle lasted five days, ending with a Japanese retreat.

Independence (1975) to present

The island is rich in copper and gold. A large mine was established at Panguna in the early 1970s by Bougainville Copper Limited, a subsidiary of Rio Tinto. Disputes by regional residents with the company over adverse environmental impacts, failure to share financial benefits, and negative social changes brought by the mine resulted in a local revival for a secessionist movement that had been dormant. Activists proclaimed the independence of Bougainville (Republic of North Solomons) in 1975 and in 1990, but both times government forces suppressed the separatists.

In 1988, the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) increased their activity significantly. Prime Minister Sir Rabbie Namaliu ordered the Papua New Guinea Defence Force (PNGDF) to put down the rebellion, and the conflict escalated into a civil war. The PNGDF retreated from permanent positions on Bougainville in 1990, but continued military action. The conflict involved pro-independence and loyalist Bougainvillean groups as well as the PNGDF. The war claimed an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 lives.[2][3]

In 1996, Prime Minister Sir Julius Chan hired Sandline International, a private military company previously involved in supplying mercenaries in the civil war in Sierra Leone, to put down the rebellion. The Sandline affair was a controversial incident that resulted from use of these mercenary troops.

Government and politics

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Bougainville |

|

The Bougainville conflict ended in 1997, after negotiations brokered by New Zealand. A peace agreement was completed in 2000 and, together with disarmament, provided for the establishment of an Autonomous Bougainville Government. The parties agreed to have a referendum in the future on whether the island should become politically independent.[4]

Elections for the first autonomous government were held in May and June 2005; Joseph Kabui, an independence leader, was elected President. He died in office on 6 June 2008. After interim elections to fill the remainder of his term, John Momis was elected as president in 2010 for a five-year term. He supports autonomy within a relationship with the national government of Papua New Guinea.

On 25 July 2005 rebel leader Francis Ona died after a short illness. A former surveyor with Bougainville Copper, Ona was a key figure in the secessionist conflict and had refused to formally join the island's peace process.

In 2015 Australia announced it will establish a diplomatic post in Bougainville for the first time.[5]

2019 independence referendum

President John Momis confirmed that Bougainville will hold an independence referendum some time before 2020 once the region has resolved some remaining issues.[6] The governments of both Bougainville and Papua New Guinea have set a tentative date of June 15, 2019 for the vote, which is the final step in the Bougainville Peace Agreement.[7] However, certain criteria on Bougainville's part must be met before any vote can occur, including having a viable economy and controlling the flow of illegal weapons.[8] As of September 27, 2017, none of these prerequisites have been met, with Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O'Neill expressing doubt that such conditions will be met before the target date of the referendum.[9] Australian Strategic Policy Institute analyst Karl Claxton said there is a wide expectation Bougainville will vote to become independent.[10]

Economy

A small percentage of the region's economy is from mining. Majority of economic growth comes from agriculture and aquaculture. The region's biodiversity, which is one of the most important in Oceania, is heavily threatened by mining activities, mostly conducted by the rich bracket of society. Mining activities have caused civil unrest in the region many times. In January 2018, a moratorium on one mine was imposed by the Papua New Guinea government, in a bid to calm civil unrest against mining in the region.[1]

Districts and LLGs

Each province in Papua New Guinea has one or more districts, and each district has one or more Local Level Government (LLG) areas. For census purposes, the LLG areas are subdivided into wards, and those into census units.[11]

| District | District Capital | LLG Name |

|---|---|---|

| Central Bougainville District | Arawa-Kieta | Arawa Rural |

| Wakunai Rural | ||

| North Bougainville District | Buka | Atolls Rural |

| Buka Rural | ||

| Kunua Rural | ||

| Nissan Rural | ||

| Selau Suir Rural | ||

| Tinputz Rural | ||

| South Bougainville District | Buin | Bana Rural |

| Buin Rural | ||

| Siwai Rural | ||

| Torokina Rural | ||

Regional leaders

Bougainville has been headed by several different types of administration: a decentralised administration headed by a Premier (as North Solomons Province from 1975 to 1990), an appointed administrator during the height of the Bougainville Civil War (from 1990 to 1995), a Premier heading the Bougainville Transitional Government (from 1995 to 1998), the co-chairmen of the Bougainville Constituent Assembly (1999), a Governor heading a provincial government as in other parts of Papua New Guinea (2000 to 2005) and the Autonomous Bougainville Government (since 2005).[12][13][14]

President of the secessionist Republic of North Solomons (1975)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| Alexis Sarei | 1975 |

Premiers (1975–1990)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| Alexis Sarei | 1975–1980 |

| Leo Hannett | 1980–1984 |

| Alexis Sarei | 1984–1987 |

| Joseph Kabui | 1987–1990 |

Administrators (1990–1995)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| Sam Tulo | 1990–1995 |

Premiers (1995–1998)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| Theodore Miriung | 1995–1996 |

| Gerard Sinato | 1996–1998 |

Bougainville Constituent Assembly co-chairmen (1999)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| Gerard Sinato and Joseph Kabui | January 1999 – December 1999 |

Governors (1999–2005)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| John Momis | 1999–2005 |

Presidents of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville (2005–present)

| Premier | Term |

|---|---|

| Joseph Kabui | 2005–2008 |

| John Tabinaman (acting) | 2008–2009 |

| James Tanis | 2009–2010 |

| John Momis | 2010–present |

See also

References

- 1 2 Davidson, Helen (10 January 2018). "Bougainville imposes moratorium on Panguna mine over fears of civil unrest". the Guardian.

- ↑ Saovana-Spriggs, Ruth (2000). "Christianity and women in Bougainville" (PDF). Development Bulletin (51): 58–60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ "EU Relations with Papua New Guinea". European Commission. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Will Marshall, "Papua New Guinea government obtains shaky weapons disposal pact in Bougainville", World Socialist Web Site, May 23, 2001. Accessed on line March 4, 2008.

- ↑ Medhora, Shalailah. "Papua New Guinea not told of Australia's plans for new diplomatic post there". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ "Bougainville confirms independence referendum before 2020 | Pacific Beat". www.radioaustralia.net.au. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ "Ball rolling on Bougainville referendum". Radio New Zealand. 2016-05-22. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ "Bougainville MP confident of ongoing international help". Radio New Zealand. 2016-05-30. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ↑ Tlozek, Eric (2017-09-27). "Bougainville independence referendum 'may not be possible': PNG PM". ABC News. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ↑ Australian Associated Press, "PNG leader apologises to Bougainville for bloody 1990s civil war", 29 January 2014 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/29/papua-new-guinea-apologises-bougainville-civil-war

- ↑ "Pacific Regional Statistics - Secretariat of the Pacific Community". www.spc.int.

- ↑ May, R. J. "8. Decentralisation: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back". State and society in Papua New Guinea: the first twenty-five years. Australian National University. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Provinces". rulers.org. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Parliamentary Education in Bougainville" (PDF). Parliament of Queensland. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

Further reading

- Oliver, Douglas (1973). Bougainville: A Personal History. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Oliver, Douglas (1991). Black Islanders: A Personal Perspective of Bougainville, 1937–1991. Melbourne: Hyland House. Repeats text from previous 1973 reference and updates with summaries of Papua New Guinea press reports on the Bougainville Crisis

- Quodling, Paul. Bougainville: The Mine And The People.

- Regan, Anthony; Griffin, Helga, eds. (2005). Bougainville Before the Crisis. Canberra: Pandanus Books.

- Pelton, Robert Young (2002). Hunter Hammer and Heaven, Journeys to Three World's Gone Mad. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-416-6.

- Gillespie, Waratah Rosemarie (2009). Running with Rebels: Behind the Lies in Bougainville's hidden war. Australia: Ginibi Productions. ISBN 978-0-646-51047-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Autonomous Region of Bougainville. |

![]()

- Autonomous Bougainville Government

- Autonomous Bougainville Government – Facebook feed

- Bougainville Inward Investment Bureau

- Full text of the Peace Agreement for Bougainville

- Constitution of Bougainville

- UN Map #4089 — United Nations map of the vicinity of Bougainville Island, PDF format

- Conciliation Resources – Bougainville Project

- The Coconut Revolution, a documentary film about the Bougainville Revolutionary Army.

- Bougainville – Our Island, Our Fight(1998) by the multi-award-winning director Wayne Coles-Janess. The first footage of the war from behind the blockade. The critically acclaimed and internationally award-winning documentary is shown around the world. Produced and directed by Wayne Coles-Janess. Production company: ipso-facto Productions

- ABC Foreign Correspondent- World in Focus – Lead Story (1997) Exclusive interview with Francis Ona. Interviewed by Wayne Coles-Janess.