Bougainville Island

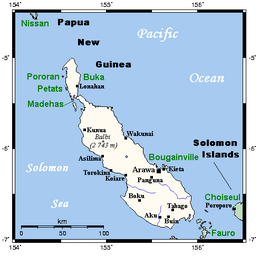

Bougainville and neighbouring islands | |

Bougainville Bougainville Island (Papua New Guinea) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Melanesia |

| Coordinates | 6°14′40″S 155°23′02″E / 6.24444°S 155.38389°E |

| Archipelago | Solomon Islands |

| Area | 9,318 km2 (3,598 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,715 m (8,907 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Balbi |

| Administration | |

|

Papua New Guinea | |

| Province | Bougainville Province |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 234,280 (2011) |

| Pop. density | 18.80 /km2 (48.69 /sq mi) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

Bougainville Island is the main island of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville of Papua New Guinea. This region is also known as Bougainville Province or the North Solomons. Its land area is 9,300 km2 (3591 sq miles). The population of the province is 234,280 (2011 census), which includes the adjacent island of Buka and assorted outlying islands including the Carterets. Mount Balbi at 2,700 m is the highest point.

Bougainville Island is the largest of the Solomon Islands archipelago, forming part of the Northern Solomon Islands, which is politically separate from the sovereign country also called Solomon Islands.

History

Bougainville was first settled some 28,000 years ago. Three to four thousand years ago, Austronesian people arrived, bringing with them domesticated pigs, chickens, dogs and obsidian tools. The first European contact with Bougainville was in 1768, when the French explorer Louis de Bougainville arrived and named the main island for himself.

Germany laid claim to Bougainville in 1899, annexing it into German New Guinea. Christian missionaries arrived on the island in 1902.

During World War I, Australia occupied German New Guinea, including Bougainville. It became part of the Australian Territory of New Guinea under a League of Nations mandate in 1920.

In 1942, during World War II, Japan invaded the island, but allied forces launched the Bougainville campaign to regain control of the island in 1943.[1][2] Despite heavy bombardments, the Japanese garrisons remained on the island until 1945. Following the war, the Territory of New Guinea, including Bougainville, returned to Australian control.

In 1949, the Territory of New Guinea, including Bougainville, merged with the Australian Territory of Papua, forming the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, a United Nations Trust Territory under Australian administration.

On 9 September 1975, the Parliament of Australia passed the Papua New Guinea Independence Act 1975. The Act set 16 September 1975 as date of independence and terminated all remaining sovereign and legislative powers of Australia over the territory. Bougainville was to become part of an independent Papua New Guinea. However, on 11 September 1975, in a failed bid for self-determination, Bougainville declared the Republic of the North Solomons. The republic failed to achieve any international recognition, and a settlement was reached in August 1976. Bougainville was then absorbed politically into Papua New Guinea with increased self-governance powers.

Between 1988 and 1998, the Bougainville Civil War claimed over 15,000 lives. Peace talks brokered by New Zealand began in 1997 and led to autonomy. A multinational Peace Monitoring Group (PMG) under Australian leadership was deployed. In 2001, a peace agreement was signed including promise of a referendum on independence from Papua New Guinea.

Geography

Bougainville is the largest island in the Solomon Islands archipelago. It is part of the Solomon Islands rain forests ecoregion. Bougainville and the nearby island of Buka are a single landmass separated by a deep 300-metre-wide strait. The island has an area of 9000 square kilometres, and there are several active, dormant or inactive volcanoes which rise to 2400 m. Mount Bagana in the north central part of Bougainville is conspicuously active, spewing out smoke that is visible many kilometres distant. Earthquakes are frequent, but cause little damage.

Ecology

The daily volume of wild rivers appears to be decreasing. This has been affected by deforestation caused by the increased demand for gardens to feed the growing population.[3] Mining with its use of chemicals and its aftereffects poses other environmental issues, e.g. alluvial gold mining and the now decommissioned Rio Tinto-owned Panguna mine.[4]

Climate

| Climate data for Bougainville | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32 (89) |

32 (89) |

31 (88) |

31 (87) |

31 (87) |

31 (87) |

30 (86) |

31 (87) |

31 (87) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

31 (87) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

22 (71) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

22 (71) |

22 (71) |

22 (71) |

22 (71) |

22 (71) |

22 (71) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 564 (22.2) |

191 (7.5) |

373 (14.7) |

290 (11.4) |

282 (11.1) |

241 (9.5) |

505 (19.9) |

323 (12.7) |

353 (13.9) |

582 (22.9) |

417 (16.4) |

488 (19.2) |

4,608 (181.4) |

| Source: Weatherbase[5] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Bougainville has one of the world's largest copper deposits. This had been under development since 1972; one of its reserves has almost 915 million tonnes of copper with an average grade of 0.46% Cu. Mining and export of copper was the basis of the economy.

Demographics

Religion

The majority of people on Bougainville are Christian, an estimated 70% being Roman Catholic and a substantial minority United Church of Papua New Guinea since 1968. Few non-natives remain as most were evacuated following the civil wars.

Languages

There are many indigenous languages in Bougainville Province, belonging to three language families. The languages of the northern end of the island, and some scattered around the coast, belong to the Austronesian family. The languages of the north-central and southern lobes of Bougainville Island belong to the North and South Bougainville families.

The most widely spoken Austronesian language is Halia and its dialects, spoken in the island of Buka and the Selau peninsula of Northern Bougainville. Other Austronesian languages include Nehan, Petats, Solos, Saposa (Taiof), Hahon and Tinputz, all spoken in the northern quarter of Bougainville, Buka and surrounding islands. These languages are closely related. Bannoni and Torau are Austronesian languages not closely related to the former, which are spoken in the coastal areas of central and south Bougainville. On the nearby Takuu Atoll a Polynesian language is spoken, Takuu.[6]

The Papuan languages are confined to the main island of Bougainville. These include Rotokas, a language with a very small inventory of phonemes, Eivo, Terei, Keriaka, Nasioi (Kieta), Nagovisi, Siwai (Motuna), Baitsi (sometimes considered a dialect of Siwai), Uisai and several others. These constitute two language families, North Bougainville and South Bougainville.

None of the languages are spoken by more than 20% of the population, and the larger languages such as Nasioi, Korokoro Motuna, Telei, and Halia are split into dialects that are not always mutually understandable. For general communication most Bougainvilleans use Tok Pisin as a lingua franca, and at least in the coastal areas Tok Pisin is often learned by children in a bilingual environment. English and Tok Pisin are the languages of official business and government.

Human rights

A 2013 United Nations survey of 843 men found that 62% (530 respondents) of those have at least once raped a woman or girl, with 41% (217 respondents) of the men reported having raped a non-partner, whereas 14% (74 respondents) reported having committed gang rape. Additionally, the survey also found that 8% (67 respondents) of the men had raped other men.[7]

Popular culture

The Coconut Revolution, a documentary about the struggle of the indigenous population to save their island from environmental destruction and gain independence was made in 1999.[8]

An Evergreen Island (2000), a film by Australian documentary filmmakers Amanda King and Fabio Cavadini of Frontyard Films, showed the ingenuity with which the Bougainvillean people survived for almost a decade without trade or contact with the outside world.[9][10][11]

Mr. Pip (2012), a film by New Zealand director Andrew Adamson based on the book Mister Pip by Lloyd Jones, is largely set in a village on Bougainville Island during the 1990s civil war.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Hall, R. Cargill (1991). Lightning Over Bougainville: The Yamamoto Mission Reconsidered. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-012-5.

- ↑ Gailey, Harry A. (1991). Bougainville, 1943–1945: The Forgotten Campaign. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1748-8.

- ↑ "Water crisis looms from deforestation; alluvial mining". Bougainville 24 – BCL news blog.

- ↑ "UNEP to help Bougainville manage clean-up of Rio Tinto mine". ABC News.

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Bougainville, Papua New Guinea". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on 24 November 2011.

- ↑ Irwin, H. (1980). Takuu Dictionary. : A Polynesian language of the South Pacific. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. 428pp. ISBN 978-0858836372.

- ↑ http://unwomen-asiapacific.org/docs/WhyDoSomeMenUseViolenceAgainstWomen_P4P_Report.pdf

- ↑ "Coconut Revolution, The (Bougainville story)".

- ↑ "An Evergreen Island". National Film and Sound Archive. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Bougainville film shows courage and community". Green Left Weekly. 26 July 2000. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ "An Evergreen Island". New Internationalist.

- ↑ "Mr. Pip". Retrieved 6 March 2018.

Bibliography

Further reading

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bougainville. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bougainville Island. |

- Robert Young Pelton, Hunter Hammer and Heaven, Journeys to Three Worlds Gone Mad. ISBN 1-58574-416-6

Coordinates: 6°14′40″S 155°23′02″E / 6.24444°S 155.38389°E