Library of Ashurbanipal

| Established | 7th century BC |

|---|---|

| Location | Nineveh, capital of Assyria |

| Collection | |

| Size | over 30,000 cuneiform tablets[1] |

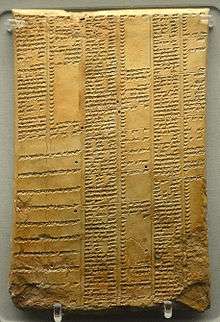

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, is a collection of thousands of clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BC. Among its holdings was the famous Epic of Gilgamesh.

Ashurbanipal's Library was buried by invaders centuries before the Library of Alexandria was erected and also gives modern historians information regarding people of the ancient Near East.

The materials were found in the archaeological site of Kouyunjik (ancient Nineveh, capital of Assyria) in northern Mesopotamia. The site is in modern-day northern Iraq, near the city of Mosul.[2][3]

Old Persian and Armenian traditions indicate that Alexander the Great, upon seeing the great library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, was inspired to create his own library. Alexander died before he was able to create his library, but his friend and successor in Egypt, Ptolemy, oversaw the beginnings of Alexander's library—a project that was to grow to become the renowned Library of Alexandria.[4]

Discovery

The library is an archaeological discovery credited to Austen Henry Layard; most tablets were taken to England and can now be found in the British Museum, but a first discovery was made in late 1849 in the so-called South-West Palace, which was the Royal Palace of king Sennacherib (705–681 BC).

Three years later, Hormuzd Rassam, Layard's assistant, discovered a similar "library" in the palace of King Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC), on the opposite side of the mound. Unfortunately, no record was made of the findings, and soon after reaching Europe, the tablets appeared to have been irreparably mixed with each other and with tablets originating from other sites. Thus, it is almost impossible today to reconstruct the original contents of each of the two main "libraries".

Contents

Ashurbanipal was known as a tenacious martial commander; however, he was also a recognized intellectual who was literate, and a passionate collector of texts and tablets.[5] As an apprentice scribe he mastered both the Akkadian and the Sumerian languages[5] He sent scribes into every region of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to collect ancient texts. He hired scholars and scribes to copy texts, mainly from Babylonian sources.[2][3]

Ashurbanipal was not above using war booty as a means of stocking his library. Because he was known for being a scholar and being cruel to his enemies, Ashurbanipal was able to use threats to gain materials from Babylonia and surrounding areas.[6] Ashurbanipal's intense interest in collecting divination texts was one of his driving motivations in collecting works for his library. His original motive may have been to "gain possession of rituals and incantations that were vital to maintain his royal power."[7]

The royal library consists of approximately 30,000 tablets and writing boards with the majority of them being severely fragmented.[8] It can be gleaned from the conservation of the fragments that the number of tablets that existed in the library at the time of destruction was close to two thousand and the number of writing boards within the library can be placed at a total of three hundred.[8] The majority of the tablet corpus (about 6,000) included colloquial compositions in the form of legislation, foreign correspondences and engagements, aristocratic declarations, and financial matters.[8] The remaining texts contained divinations, omens, incantations and hymns to various gods, while others were concerned with medicine, astronomy, and literature. For all these texts in the library only ten contain expressive rhythmic literary works such as epics and myths.[8]

The Babylonian texts of the Ashurbanipal libraries can be separated into two different groups: the literary compositions such as divination, religious, lexical, medical, mathematical and historical texts as well as epics and myths, on the one hand, and the legal documents on the other hand. The group of the legal documents covers letters, contracts and administrative texts and consists of 1128 Babylonian tablets and fragments. Within the group of the literary compositions, of which 1331 tablets and fragments are classified so far, the divination texts can further be differentiated between 759 so-called library texts, such as tablets of the various omen series and their commentaries, and 636 so-called archival texts such as omen reports, oracle enquiries and the like.[9]

The Epic of Gilgamesh, a masterpiece of ancient Babylonian poetry, was found in the library, as was the Enûma Eliš creation story, the myth of Adapa, the first man, and stories such as the Poor Man of Nippur.[10][11][12]

Another group of literary texts is the lexical texts and sign lists. There are twenty fragments of different tablets with archaic cuneiform signs arranged according to the syllabary A, whereas one is arranged according to the syllabary B. The Assyrian scribes of the Ashurbanipal Libraries needed sign lists to be able to read the old inscriptions and most of these lists were written by Babylonian scribes! The other groups of Babylonian written texts in Nineveh are the epics and myths and the historical texts with 1.4% each. There is only one mathematical text that is said to be excavated at Nineveh.[13]

The texts were principally written in Akkadian in the cuneiform script; however many of the tablets do not have an exact derivation and it is often difficult to ascertain their original homeland. Many of the tablets are indeed composed in the Neo-Babylonian Script, but many were also known to be written in Assyrian as well.[8]

The tablets were often organized according to shape: four-sided tablets were for financial transactions, while round tablets recorded agricultural information.(In this era, some written documents were also on wood and others on wax tablets.) Tablets were separated according to their contents and placed in different rooms: government, history, law, astronomy, geography, and so on. The contents were identified by colored marks or brief written descriptions, and sometimes by the "incipit," or the first few words that began the text.[14]

Nineveh was destroyed in 612 BC by a coalition of Babylonians, Scythians and Medes, an ancient Iranian people. It is believed that during the burning of the palace, a great fire must have ravaged the library, causing the clay cuneiform tablets to become partially baked.[11] This potentially destructive event helped preserve the tablets. As well as texts on clay tablets, some of the texts may have been inscribed onto wax boards which, because of their organic nature, have been lost.

The British Museum’s collections database counts 30,943 "tablets" in the entire Nineveh library collection, and the Trustees of the Museum propose to issue an updated catalogue as part of the Ashurbanipal Library Project.[15] If all smaller fragments that actually belong to the same text are deducted, it is likely that the "library" originally included some 10,000 texts in all. The original library documents however, which would have included leather scrolls, wax boards, and possibly papyri, contained perhaps a much broader spectrum of knowledge than that known from the surviving clay tablet cuneiform texts. Certainly, we must expect that a large share of Ashurbanipal's libraries consisted of writing-boards and not clay tablets.[16]

List of significant tablets

- Azekah Inscription

- Esarhaddon's Treaty with Ba'al of Tyre

- Nimrud Tablet K.3751

- Sargon II's Prism A

- Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa

- Epic of Gilgamesh

- Enûma Eliš

See also

References

- ↑ Ashurbanipal Library Project (phase 1) from the British Museum

- 1 2 Polastron, Lucien X.: "Books On Fire: The Tumultuous Story Of The World's Great Libraries" 2007, pages 2-3, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

- 1 2 Menant, Joachim: "La bibliothèque du palais de Ninive" 1880, Paris: E. Leroux

- ↑ Phillips, Heather A., "The Great Library of Alexandria?". Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010

- 1 2 Roaf, M. (1990). Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East. New York: Facts on File.

- ↑ "Assurbanipal's Library" Archived 2012-08-25 at WebCite, Knowledge and Power in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, British Museum

- ↑ Fincke, Jeanette (2004). "The British Museum's Ashurbanipal Library Project". Iraq, 66, Ninevah.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parpola, S. (1983). Assyrian Library Records. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 42(1), 1-29.

- ↑ Jeanette C., Fincke. "The British Museum's Ashurbanipal Library Project." Iraq, 2004, p. 55.

- ↑ Jeanette C. Fincke (2003-12-05). "Nineveh Tablet Collection". Fincke.uni-hd.de. Archived from the original on 2011-12-29. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- 1 2 Polastron, Lucien X.: "Books On Fire: The Tumultuous Story Of The World's Great Libraries" 2007, page 3, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

- ↑ Menant, Joachim: "La bibliothèque du palais de Ninive" 1880, page 33, Paris: E. Leroux, "Quels sont maintenant ces livres qui étaient recueillis et conservés avec tant de soin par les rois d'Assyrie dans ce précieux dépôt ? Nous y trouvons des livres sur l'histoire, la religion, les sciences naturelles, les mathématiques, l'astronomie, la grammaire, les lois et les coutumes; ..."

- ↑ Jeanette C., Fincke. "The British Museum's Ashurbanipal Library Project." Iraq, 2004, p. 55.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009) The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago, IL: Skyhorse Publishing (p.9)

- ↑ "Ashurbanipal Library Phase 1". Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ↑ Jeanette C., Fincke. "The British Museum's Ashurbanipal Library Project." Iraq, 2004, p. 55.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Library of Ashurbanipal. |

External links

- BBC audio file. In our time discussion programme. 45 minutes.