Fur

Fur is the hair covering of non-human mammals, particularly those mammals with extensive body hair that is soft and thick. The stiffer bristles on animals such as pigs are not generally referred to as fur.

The term pelage – first known use in English c. 1828 (French, from Middle French, from poil for "hair", from Old French peilss, from Latin pilus[1]) – is sometimes used to refer to the body hair of an animal as a complete coat. Fur is also used to refer to animal pelts which have been processed into leather with the hair still attached. The words fur or furry are also used, more casually, to refer to hair-like growths or formations, particularly when the subject being referred to exhibits a dense coat of fine, soft "hairs". If layered, rather than grown as a single coat, it may consist of short down hairs, long guard hairs, and in some cases, medium awn hairs. Mammals with reduced amounts of fur are often called "naked", as with the naked mole-rat, or "hairless", as with hairless dogs.

An animal with commercially valuable fur is known within the fur industry as a furbearer.[2] The use of fur as clothing or decoration is controversial; animal welfare advocates object to the trapping and killing of wildlife, and to the confinement and killing of animals on fur farms.

Composition

The modern mammalian fur arrangement is known to have occurred as far back as docodonts, haramiyidans and eutriconodonts, with specimens of Castorocauda, Megaconus and Spinolestes preserving compound follicles with both guard hair and underfur.

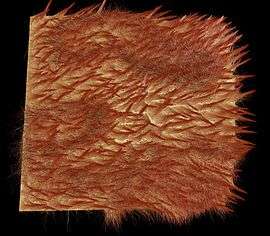

Fur may consist of three layers, each with a different type of hair.

Down hair

Down hair (also known as undercoat or ground hair) is the bottom—or inner—layer, composed of wavy or curly hairs with no straight portions or sharp points. Down hairs, which are also flat, tend to be the shortest and most numerous in the coat. Thermoregulation is the principal function of the down hair, which insulates a layer of dry air next to the skin.

Awn hair

The awn hair can be thought of as a hybrid, bridging the gap between the distinctly different characteristics of down and guard hairs. Awn hairs begin their growth much like guard hairs, but less than half way to their full length, awn hairs start to grow thin and wavy like down hair. The proximal part of the awn hair assists in thermoregulation (like the down hair), whereas the distal part can shed water (like the guard hair). The awn hair's thin basal portion does not allow the amount of piloerection that the stiffer guard hairs are capable of. Mammals with well developed down and guard hairs also usually have large numbers of awn hairs, which may even sometimes be the bulk of the visible coat.

Guard hair

Guard hair is the top—or outer—layer of the coat. Guard hairs are longer, generally coarser, and have nearly straight shafts that protrude through the layer of softer down hair. The distal end of the guard hair is the visible layer of most mammal coats. This layer has the most marked pigmentation and gloss, manifesting as coat markings that are adapted for camouflage or display. Guard hair repels water and blocks sunlight, protecting the undercoat and skin in wet or aquatic habitats, and from the sun's ultraviolet radiation. Guard hairs can also reduce the severity of cuts or scratches to the skin. Many mammals, such as the domestic dog and cat, have a pilomotor reflex that raises their guard hairs as part of a threat display when agitated.

Mammals without fur

Computer-generated

Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals; however, several species or breeds have considerably reduced amounts of fur. These are often called "naked" or "hairless".

Natural selection

Some mammals naturally have reduced amounts of fur. Some semiaquatic or aquatic mammals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds and hippopotamuses have evolved hairlessness, presumably to reduce resistance through water. The naked mole-rat has evolved hairlessness, perhaps as an adaptation to their subterranean life-style. Two of the largest extant mammals, the elephant and the rhinoceros, are largely hairless. The hairless bat is mostly hairless but does have short bristly hairs around its neck, on its front toes, and around the throat sac, along with fine hairs on the head and tail membrane. Most hairless animals cannot go in the sun for long periods of time, or stay in the cold for too long. [3]

Humans are the only primate species that have undergone significant hair loss. The hairlessness of humans compared to related species may be due to loss of functionality in the pseudogene KRTHAP1 (which helps produce keratin) in the human lineage about 240,000 years ago.[4] Mutations in the gene HR can lead to complete hair loss, though this is not typical in humans.[5]

Sheep have not become hairless; however, their pelage is usually referred to as "wool" rather than fur.

Artificial selection

At times, when a hairless domesticated animal is discovered, usually owing to a naturally occurring genetic mutation, humans may intentionally inbreed those hairless individuals and, after multiple generations, artificially create breeds that are hairless. There are several breeds of hairless cats, perhaps the most commonly known being the Sphynx cat. Similarly, there are several breeds of hairless dogs. Other examples of artificially selected hairless animals include the hairless guinea-pig, nude mouse, and the hairless rat.

Use in clothing

Carl Ben Eielson (1897-1929)

USAF pilot & Arctic explorer

In clothing, fur is usually leather with the hair retained for its aesthetic and insulating properties. Fur has long served as a source of clothing for humans, including Neanderthals. Animal furs used in garments and trim may be dyed bright colors or to mimic exotic animal patterns, or shorn down to imitate the feel of a soft velvet fabric. The term "a fur" is often used to refer to a fur coat, wrap, or shawl.

Usual animal sources for fur clothing and fur trimmed accessories include fox, rabbit, mink, beavers, ermine, otters, sable, seals, coyotes, chinchilla, raccoon, and possum. The import and sale of seal products was banned in the U.S. in 1972 over conservation concerns about Canadian seals. The import and sale is still banned even though the Marine Animal Response Society estimates the harp seal population is thriving at approximately 8 million.[6] The import, export and sales of domesticated cat and dog fur were also banned in the U.S. under the Dog and Cat Protection Act of 2000.[7]

The manufacturing of fur clothing involves obtaining animal pelts where the hair is left on the animal's processed skin. In contrast, making leather involves removing the hair from the hide or pelt and using only the skin. The use of wool involves shearing the animal's fleece from the living animal, so that the wool can be regrown but sheepskin shearling is made by retaining the fleece to the leather and shearing it.[8] Shearling is used for boots, jackets and coats and is probably the most common type of skin worn.

Fur is also used to make felt. A common felt is made from beaver fur and is used in high-end cowboy hats.[9]

History

Fur clothing predates written history and has been recovered from various archaeological sites world wide. The kings and queens of England ordered proclamations to regulate fur aka “sumptuary legislation”.[10] Sumptuary legislation established the stigmatism of fur being limited to the higher social statuses and convey the idea of exclusivity. Exotic furs such as fox, marten, grey squirrel and ermine were reserved for aristocratic elites. The middle class were known to wear fox, hare and beaver while the less fortunate wore goat, wolf and sheepskin. Due to clothing being loose and garments were known to be layered, fur was primarily used for visible linings. Different kinds of fur were worn during seasons and social classes. Animals with fur decreased in West Europe and began to be imported from the Middle East and Russia.[11]

As new kinds of fur entered Europe, other uses were made with fur other than clothing. Beaver was most desired but used to make hats which became a popular headpiece especially during the wartime. Swedish soldiers wore broad-brimmed hats made exclusively from beaver felt. Due to the limitations of beaver fur, hat-makers relied heavily on North America for imports as beaver was only available in the Scandinavian peninsula.[12]

Other than the military, fur has been used for accessories such as hats, hoods, scarves, and muffs. Design elements including the visuals of the animal were considered acceptable with heads, tails and paws still being kept on the accessories. During the ninetieth century, seal and karakul were made into indoor jackets. The twentieth century was the beginning of the fur coats being fashionable in West Europe with full fur coats. With lifestyle changes as a result of developments like indoor heating, the international textile trade affected how fur was distributed around the world. Europeans focused on using local resources giving fur association with femininity with the increasing use of mink. In 1970, Germany was the world’s largest fur market. The International Fur Trade Federation banned endangering species furs like silk monkey, ocelot, leopard, tiger, and polar bear in 1975. The use of animal skins were brought to light during the 1980s by animal right organisations and the demand for fur decreased. Anti-fur organisations raised awareness of the controversy between animal welfare and fashion. Fur farming became banned in Britain in 1999. During the twenty-first century, fox and mink have been bred in captivity with Denmark, Holland and Finland being leaders of mink production. [13]

Awn hair (#3-4)

Guard hairs (#5-8)

Domestic tabby cat

Controversy

Most animal rights activists are opposed to the trapping and killing of wildlife, and the confinement and killing of animals on fur farms. According to Humane Society International, over 8 million animals are trapped yearly for fur, while more than 30 million were raised in fur farms.[14]

According to Statistics Canada, 2.6 million fur-bearing animals raised on farms were killed in 2010. Another 700,000 were killed for fur by traps.[15][16]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pelage". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ↑ Peterson, Judy Monroe (2011-01-15). Varmint Hunting. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 9781448823666.

- ↑ Thomson, Paul (2002). "Cheiromeles torquatus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ↑ Winter, H.; Langbein, L.; Krawczak, M.; Cooper, D. N.; Jave-Suarez, L. F.; Rogers, M. A.; Praetzel, S.; Heidt, P. J.; Schweizer, J. (2001). "Human type I hair keratin pseudogene phihHaA has functional orthologs in the chimpanzee and gorilla: Evidence for recent inactivation of the human gene after the Pan-Homo divergence". Human Genetics. 108 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1007/s004390000439. PMID 11214905.

- ↑ "Molecular evolution of HR, a gene that regulates the postnatal cycle of the hair follicle". Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ↑ "Harp Seal", Marine Animal Response Society.

- ↑ Rules and Regulations Under the Fur Products Labeling Act Archived 2008-07-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Australian Wool Corporation, Australian Wool Classing, Raw Wool Services, 1990.

- ↑ Chamber's journal, Published by Orr and Smith, 1952, p. 200, Original from the University of Michigan.

- ↑ "Savannah College of Art and Design". 0-www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com.library.scad.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- ↑ "Savannah College of Art and Design". 0-www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com.library.scad.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- ↑ "Savannah College of Art and Design". 0-www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com.library.scad.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- ↑ "Savannah College of Art and Design". 0-www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com.library.scad.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- ↑ Humane Society International Fur Trade

- ↑ "Fur production, by province and territory"

- ↑ The fur industry. Peta, n.d.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Furs. |