Amrita Sher-Gil

| Amrita Sher-Gil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

30 January 1913 Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Died |

5 December 1941 (aged 28) Lahore, British India (today Pakistan) |

| Nationality | Hungarian / British Indian |

| Education |

Grande Chaumiere École des Beaux-Arts (1930–34) |

| Known for | Painting |

Amrita Sher-Gil (30 January 1913 – 5 December 1941) was an eminent Hungarian-Indian painter. She has been called "one of the greatest avant-garde women artists of the early 20th century" and a "pioneer" in modern Indian art.[1] Drawn towards painting since a young age, Sher-Gil started getting formal lessons in the art, at the age of eight. She first gained recognition at the age of 19, for her oil painting titled- Young Girls (1932).

Sher-Gil traveled throughout her life to various countries including Turkey, France, and India, deriving heavily from their art styles and cultures. Sher-Gil is considered an important painter of 20th-century India, whose legacy stands on a level with that of the pioneers from the Bengal Renaissance.[2][3] She was also an avid reader and a pianist. Sher-Gil's paintings are among the most expensive by Indian women painters today, although few acknowledged her work when she was alive.[4][5] Her letters reveal same-sex affairs.[6]

Early life and education

Amrita Sher-Gil was born on 30 January 1913[7] in Budapest, Hungary,[8] to Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Majithia, a Jat sikh aristocrat and a scholar in Sanskrit and Persian, and Marie Antoniette Gottesmann, a Hungarian-Jewish opera singer who came from an affluent bourgeois family.[9][1] Her parents first met in 1912, while Marie Antoinette was visiting Lahore.[9] Her mother came to India as a companion of Princess Bamba Sutherland, the granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.[10][11] Sher-Gil was the elder of two daughters; her younger sister was Indira Sundaram (née Sher-Gil), born in March 1914), mother of the contemporary artist Vivan Sundaram. She spent most of early childhood in Budapest.[9] She was the niece of Indologist Ervin Baktay. Baktay noticed Sher-Gil's artistic talents during his visit to Shimla in 1926 and was an advocate of Sher-Gil pursuing art.[1] He guided her by critiquing her work and gave her an academic foundation to grow on. When she was a young girl she would paint the servants in her house, and get them to model for her.[12] The memories of these models would eventually lead to her return to India.[13]

Her family faced financial problems in Hungary. In 1921, her family moved to Summer Hill, Shimla, India, and Sher-Gil soon began learning piano and violin.[12] By age nine she, along with her younger sister Indira, was giving concerts and acting in plays at Shimla's Gaiety Theatre at Mall Road, Shimla.[14] Though she was already painting since the age of five she formally started learning painting at age eight.[14] Sher-Gil started getting formal lessons in the art by Major Whitmarsh, who was later replaced by Beven Pateman. In Shimla Sher-Gil lived a relatively privileged lifestyle.[9] As a child, she was expelled from her convent school for declaring herself an atheist.[9]

In 1923, Marie came to know an Italian sculptor, who was living at Shimla at the time. In 1924, when he returned to Italy, she too moved there along with Amrita and got her enrolled at Santa Annunziata, an art school at Florence. Though Amrita didn't stay at this school for long and returned to India in 1924, it was here that she was exposed to works of Italian masters.[15]

At sixteen, Sher-Gil sailed to Europe with her mother to train as a painter at Paris, first at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière under Pierre Vaillent and Lucien Simon (where she met Boris Taslitzky) and later at the École des Beaux-Arts (1930–34).[16][17] She drew inspiration from European painters such as Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin,[18] while working under the influence of her teacher Lucien Simon and the company of artist friends and lovers like Tazlitsky. While in Paris she is said to have painted with a conviction and maturity rarely seen in a 16-year old.[1]

In 1931 Sher-Gil was briefly engaged to Yusuf Ali Khan, but rumors spread that she was also having an affair with her first cousin and later husband Victor Egan.[19]

Career

1932–1936: Early career, European and Western styles

Sher-Gil's early paintings display a significant influence of the Western modes of painting, especially as practiced in the Bohemian circles of Paris in the early 1930s. Her 1932 oil painting, Young Girls, came as a breakthrough for her; the work won her accolades, including a gold medal and election as an Associate of the Grand Salon in Paris in 1933. She was the youngest ever member,[20][21][22] and the only Asian to have received this recognition.[15] Her work during this time include a number of self-portraits, as well as life in Paris, nude studies, still life studied, and portraits of friends and fellow students.[23] The National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi describes her self-portraits she made while in Paris as "[capturing] the artist in her many moods – somber, pensive, and joyous – while revealing a narcissistic streak in her personality." [23]

When she was in Paris one of her professors often said that judging by the richness of her coloring that Sher-Gil was not in her element in the west, and that her artistic personality would find its true atmosphere in east.[5] In 1933, Sher-Gil "began to be haunted by an intense longing to return to India [...] feeling in some strange way that there lay my destiny as a painter." Sher-Gill returned to India at the end of 1934.[24][5] In May 1935, Sher-Gil met the English journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, then working as Assistant Editor and leader writer for The Calcutta Statesman.[25] Both Muggeridge and Sher-Gil stayed at the family home at Summer Hill, Shimla and a short intense affair took place during which she painted a casual portrait of her new lover, the painting now with the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi. By September 1935 Amrita saw Muggeridge off as he traveled back to England for new employment.[26] She left herself for travel in 1936 at the behest of an art collector and critic, Karl Khandalavala, who encouraged her to pursue her passion for discovering her Indian roots.[18] In India, she began a quest for the rediscovery of the traditions of Indian art which was to continue till her death. She was greatly impressed and influenced by the Mughal and Pahari schools of painting and the cave paintings at Ajanta.

1937–1941: Later career, influence of Indian art

Later in 1937, she toured South India[18] and produced her South Indian trilogy of paintings Bride's Toilet, Brahmacharis, and South Indian Villagers Going to Market following her visit to the Ajanta caves, when she made a conscious attempt to return to classical Indian art. These paintings reveal her passionate sense of colour and an equally passionate empathy for her Indian subjects, who are often depicted in their poverty and despair.[27] By now the transformation in her work was complete and she had found her 'artistic mission' which was, according to her, to express the life of Indian people through her canvas.[7] While in Saraya Sher-Gil wrote to a friend thus: "I can only paint in India. Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque.... India belongs only to me".[28] Her stay in India marks the beginning of a new phase in her artistic development, one that was distinct from the European phase of the interwar years when her work showed an engagement with the works of Hungarian painters, especially the Nagybanya school of painting.[29]

Sher-Gil married her Hungarian first cousin, Dr. Victor Egan when she was 25.[9] Dr. Egan had helped Sher-Gil obtain abortions on at least two occasions prior to their marriage.[9] She moved with him to India to stay at her paternal family's home in Saraya, Sardar nagar, Chauri Chaura in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh. Thus began her second phase of painting which equals in its impact on Indian art with the likes of Rabindranath Tagore and Jamini Roy of the Bengal school of art. The 'Calcutta Group' of artists, which transformed the Indian art scene, was to start only in 1943, and the 'Progressive Artist's Group', with Francis Newton Souza, Ara, Bakre, Gade, M. F. Husain and S. H. Raza among its founders, lay further ahead in 1948.[30][31][32] Amrita's art was strongly influenced by the paintings of the two Tagores, Rabindranath and Abanindranath who were the pioneers of the Bengal School of painting. Her portraits of women resemble works by Rabindranath while the use of 'chiaroscuro' and bright colours reflect the influence of Abanindranath.[33]

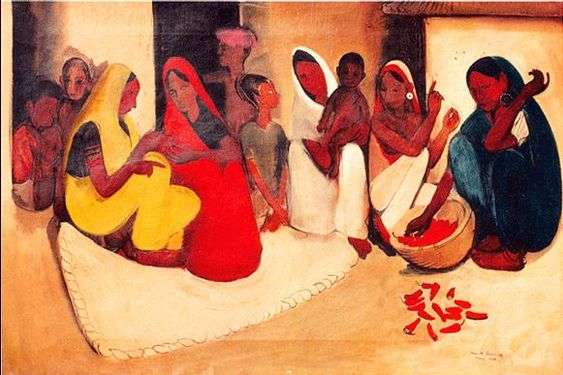

It was during her stay at Saraya that she painted the Village Scene, In the Ladies' Enclosure and Siesta all of which portray the leisurely rhythms of life in rural India. Siesta and In the Ladies' Enclosure reflect her experimentation with the miniature school of painting while Village Scene reflects influences of the Pahari school of painting.[34] Although acclaimed by art critics Karl Khandalavala in Bombay and Charles Fabri in Lahore as the greatest painter of the century, Amrita's paintings found few buyers. She travelled across India with her paintings but the Nawab Salar Jung of Hyderabad returned them and the Maharaja of Mysore chose Ravi Varma's paintings over hers.[35]

Although from a family that was closely tied to the British Raj, Amrita herself was a Congress sympathiser. She was attracted to the poor, distressed and the deprived and her paintings of Indian villagers and women are a meditative reflection of their condition. She was also attracted by Gandhi's philosophy and lifestyle. Nehru was charmed by her beauty and talent and when he went to Gorakhpur in October 1940, he visited her at Saraya. Her paintings were at one stage even considered for use in the Congress propaganda for village reconstruction.[28] However, despite being friends with Nehru Sher-Gil never drew his portrait, supposedly because the artist thought he was "too good looking."[36] Nehru attended her exhibition held in New Delhi in February 1937.[36] Sher-Gil exchanged letters with Nehru for a time, but those letters were burned by her parents when she was away getting married in Budapest.[36]

In September 1941, Victor and Amrita moved to Lahore, then in undivided India and a major cultural and artistic centre. She lived and painted at 23 Ganga Ram Mansions, The Mall, Lahore where her studio was on the top floor of the townhouse she inhabited. Amrita was known for her many affairs with both men and women[24] and many of the latter she also painted. Her work Two Women is thought to be a painting of herself and her lover Marie Louise.[37] Some of her later works include Tahitian (1937), Red Brick House (1938), Hill Scene (1938), and The Bride (1940) among others. Her last work was left unfinished by her just prior to her death in December 1941.

In 1941, at age 28, just days before the opening of her first major solo show in Lahore, she became seriously ill and slipped into a coma.[24][38][39] She later died around midnight[27] on 6 December 1941, leaving behind a large volume of work. The reason for her death has never been ascertained. A failed abortion and subsequent peritonitis have been suggested as possible causes for her death.[40] Her mother accused her doctor husband Victor of having murdered her. However, the day after her death Britain declared war on Hungary and Victor was sent to jail as a national enemy. Amrita was cremated on 7 December 1941 at Lahore.[35]

Legacy

Sher-Gil's art has influenced generations of Indian artists from Sayed Haider Raza to Arpita Singh and her depiction of the plight of women has made her art a beacon for women at large both in India and abroad.[41] The Government of India has declared her works as National Art Treasures,[30][12] and most of them are housed in the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi.[42][23] Some of her paintings also hang at the Lahore Museum.[43] A postage stamp depicting her painting 'Hill Women' was released in 1978 by India Post, and the Amrita Shergil Marg is a road in Lutyens' Delhi named after her. Her work is deemed to be so important to Indian culture that when it is sold in India, the Indian government has stipulated that the art must stay in the country – fewer than ten of her works have been sold globally.[19] In 2006, her painting Village Scene sold for ₹6.9 crores at an auction in New Delhi which was at the time the highest amount ever paid for a painting in India.[34]

The Indian cultural center in Budapest is named the Amrita Sher-Gil Cultural Center.[38] Contemporary artists in India have recreated and reinterpreted her works.[44]

Besides remaining an inspiration to many a contemporary Indian artists, in 1993, she also became the inspiration behind the Urdu play Tumhari Amrita.[45][12]

UNESCO announced 2013, the 100th anniversary of Sher-Gil's birth, to be the international year of Amrita Sher-Gil.[46]

Sher-Gil's work is a key theme in the contemporary Indian novel Faking It by Amrita Chowdhury.[47]

Aurora Zogoiby, a character in Salman Rushdie's 1995 novel The Moor's Last Sigh, was inspired by Sher-Gil.[48]

Sher-Gil was sometimes known as India's Frida Kahlo because of the "revolutionary" way she blended Western and traditional art forms.[9][30]

In 2018, The New York Times published a belated obituary for her.[49]

Gallery

Self-portrait, 1930

Self-portrait, 1930 Self-portrait (untitled), 1931

Self-portrait (untitled), 1931 Klarra Szepessy, 1932

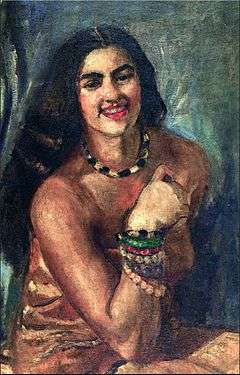

Klarra Szepessy, 1932 Hungarian Gypsy Girl, 1932

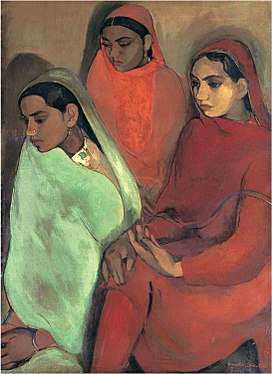

Hungarian Gypsy Girl, 1932 Group of Three Girls, 1935

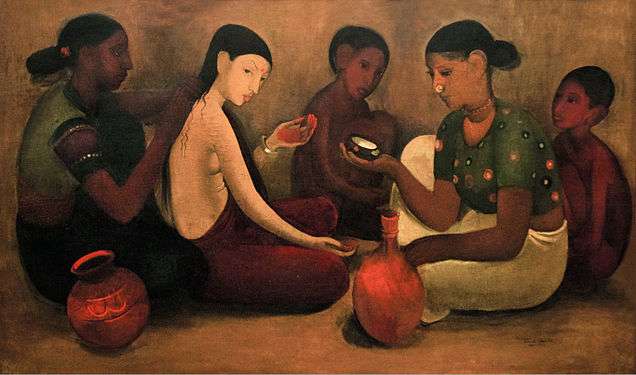

Group of Three Girls, 1935 Bride's Toilet, 1937

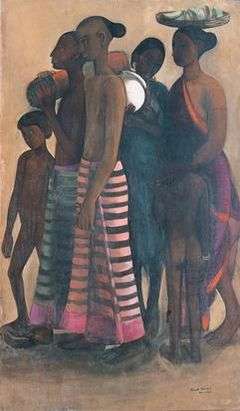

Bride's Toilet, 1937 Village Scene, 1938

Village Scene, 1938

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Revolution personified | Christie's'". Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ First Lady of the Modern Canvas Indian Express, 17 October 1999.

- ↑ Women painters at 21stcenturyindianart.com Archived 20 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Most expensive Indian artists. Us.rediff.com.

- 1 2 3 Dalmia, Yashodhara (2014). Amrita Sher-Gil: Art & Life: A Reader. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-809886-7.

- ↑ (Some names have been changed to protect their identities). "A life not so gay". Telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 2018-06-23.

- 1 2 Great Minds, The Tribune, 12 March 2000.

- ↑ "Budapest Diary". Outlook. 20 September 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Indian Frida Kahlo". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ Kang, Kanwarjit Singh (20 September 2009). "The Princess who died unknown". The Sunday Tribune. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Singh, Khushwant (27 March 2006). "Hamari Amrita". Outlook. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Google's Doodle Honours Amrita Sher-Gil. Here Are 5 Things You Should Know about Her". The Better India. 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ On Amrita Sher-Gil: Claiming a Radiant Legacy By Nilima Sheikh

- 1 2 Amrita Shergill at sikh-heritage. Sikh-heritage.co.uk (30 January 1913).

- 1 2 Amrita Shergill Biography at. Iloveindia.com (6 December 1941).

- ↑ Archives 'Amrita Shergil' project www.hausderkunst.de.

- ↑ Amrita Sher-Gil profile at. Indianartcircle.com.

- 1 2 3 Amrita Sher-Gil Exhibition at tate.org

- 1 2 Singh, Rani. "Undiscovered Amrita Sher-Gil Self-Portrait And Rare Indian Emerald Bangles Up For Auction". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ Anand, Armita Sher-Gil

- ↑ Works in Focus, Tate Modern, 2007.

- ↑ Amrita Shergil at tate. En.ce.cn.

- 1 2 3 "National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi". www.ngmaindia.gov.in. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- 1 2 3 Laid bare – the free spirit of Indian art The Daily Telegraph, 24 February 2007.

- ↑ Bright-Holmes, John (1981). Like It Was: The Diaries of Malcolm Muggeridge. entry dated 18 January 1951: Collins. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-688-00784-3.

- ↑ Wolfe, Gregory (2003). Malcolm Muggeridge: A Biography. page 136-137: Intercollegiate Studies Institute. p. 136. ISBN 1932236066.

- 1 2 Amrita Shergill at. Indiaprofile.com (6 December 1941).

- 1 2 "Amrita's village". Frontline. 30 (04). February–March 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Daily Times, 15 December 2004. Dailytimes.com.pk (15 December 2004).

- 1 2 3 Amrita Sher-Gill at. Mapsofindia.com.

- ↑ Contemporary Art Movements in India. Contemporaryart-india.com.

- ↑ Indian artists. Art.in.

- ↑ "Art into life". HT Mint. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- 1 2 "White Shadows". Outlook. 20 March 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Hamari Amrita". Outlook. 27 March 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Why Amrita Sher-Gil refused to draw Nehru's portrait : Art and Culture". indiatoday.intoday.in. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ "Passion And Precedent". Outlook. 21 December 1998. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Great success in a short life | The Budapest Times". budapesttimes.hu. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ "Amrita Sher-Gil: This Is Me, Incarnations: India in 50 Lives – BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ Truth, Love and a Little Malice, An Autobiography by Khushwant Singh Penguin, 2003. ISBN 0-14-302957-6.

- ↑ "Sad In Bright Clothes". Outlook. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Amrita Sher-Gil at. Culturalindia.net (30 January 1913).

- ↑ Dutt, Nirupama. "When Amrita Sher-Gil vowed to seduce Khushwant Singh to take revenge on his wife". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ "Two artists are recreating painter Amrita Sher-Gil's self portraits". hindustantimes.com/. 2017-03-23. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ Digital encounters The Hindu, 13 August 2006]

- ↑ "Amrita Sher-Gil in Paris | Magyar Művészeti Akadémia". www.mma.hu. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ↑ Faking It – Amrita V Chowdhury. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Amrita Sher-Gil: A Self-Portrait in Letters and Writings", ed. Vivan Sundaram, Tulika Books, 2010

- ↑ "Overlooked No More: Amrita Sher-Gil, a Pioneer of Indian Art". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-06-23.

Further reading

- Amrita Sher-Gil, by Karl J. Khandalavala. New Book Co., 1945

- Amrita Sher-Gil: Essays, by Vivan Sundaram, Marg Publications; New Delhi, 1972.

- Amrita Sher-Gil, by Baldoon Dhingra. Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi, 1981. ISBN 0-86186-644-4.

- Amrita Sher-Gil and Hungary, by Gyula Wojtilla . Allied Publishers, 1981.

- Amrita Sher-Gil: A Biography by N. Iqbal Singh, Vikas Publishing House Pvt.Ltd., India, 1984. ISBN 0-7069-2474-6

- Amrita Sher-Gil: A personal view, by Ahmad Salim. Istaarah Publications; 1987.

- Amrita Sher-Gil, by Mulk Raj Anand. National Gallery of Modern Art; 1989.

- Amrita Shergil: Amrita Shergil ka Jivan aur Rachana samsar, by Kanhaiyalal Nandan. 2000.

- Re-take of Amrita, by Vivan Sundaram. 2001, Tulika. ISBN 81-85229-49-X

- Amrita Sher Gil – A Painted Life by Geeta Doctor, Rupa 2002, ISBN 81-7167-688-X

- Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life by Yashodhara Dalmia, 2006. ISBN 0-670-05873-4

- Amrita Sher-Gil: An Indian Artist Family of the Twentieth Century, by Vivan Sundaram, 2007, Schirmer/Mosel. ISBN 3-8296-0270-7

- Amrita Sher-Gil: A Self-Portrait in Letters and Writings edited by Vivan Sundaram, Tulika Books, 2010.

- Feminine Fables: Imaging the Indian Woman in Painting, Photography and Cinema, by Geeti Sen, Mapin Publishing, 2002.

- The Art of Amrita Sher-Gil, Series of the Roerich Centre of Art and Culture. Allahabad Block Works, 1943.

- Sher-Gil, by Amrita Sher-Gil, Lalit Kala Akademi, 1965.

- India’s 50 Most Illustrious Women by Indra Gupta ISBN 81-88086-19-3

- Famous Indians of the 20th century by Vishwamitra Sharma. Pustak Mahal, 2003, ISBN 81-223-0829-5

- When was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India, by Geeta Kapur, 2000.

- Rahman, Maseeh (6 October 2014). "In the shadow of death". The Arts. India Today. 39 (40): 68–69.

Bibliography

- Anand, Mulk Raj (1989). Amrita Sher-Gill (English). Jaipur: National Gallery of Modern Art.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amrita Sher-Gil. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Amrita Sher-Gil |