Air France Flight 4590

Flight 4590 during takeoff | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 25 July 2000 |

| Summary | Foreign object damage caused by mechanical failure on McDonnell Douglas DC-10, leading to in-flight fire and loss of control |

| Site | Gonesse, France |

| Total fatalities | 113 (109 on the aircraft, 4 on the ground) |

| First aircraft | |

Concorde F-BTSC, the aircraft involved, seen at Charles de Gaulle Airport in 1985 | |

| Type | Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde |

| Operator | Air France |

| Registration | F-BTSC |

| Flight origin | Charles de Gaulle Airport |

| Destination | John F. Kennedy International Airport |

| Passengers | 100 |

| Crew | 9 |

| Fatalities | 109 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Second aircraft | |

.jpg) The DC-10 involved, seen here some years before the accident, operated by Eastern Airlines at London Gatwick Airport[1] | |

| Type | McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 |

| Operator | Continental Airlines |

| Registration | N13067 |

| Flight origin | Charles de Gaulle Airport |

| Destination | Newark International Airport |

Air France Flight 4590 was an international charter flight from Paris to New York City on the Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde. On 25 July 2000 at 16:43 Central European Time, the aircraft serving the flight (registration F-BTSC) ran over debris on the runway during takeoff, blowing a tyre and puncturing a fuel tank. The subsequent fire and engine failure caused the aircraft to crash into a hotel in nearby Gonesse two minutes after takeoff, killing all 100 passengers and nine crew aboard and four in the hotel, with another person in the hotel being critically injured.

The flight was chartered by German company Peter Deilmann Cruises, and the passengers were on their way to board the cruise ship MS Deutschland in New York City for a 16-day cruise to Manta, Ecuador.[2][3] This was the only fatal Concorde accident during its 27-year operational history.

Event summary

Post-accident investigation revealed that the aircraft was at or over the maximum takeoff weight for ambient temperature and other conditions, and 810 kilograms (1,790 lb) over the maximum structural weight,[BEA 1][4][5][6] loaded so that the centre of gravity was aft of the take-off limit.[BEA 2][5][6] Fuel transfer during taxiing left the number 5 wing tank 94 percent full.[BEA 3] A 12-inch spacer normally keeps the left main landing gear in alignment, but it had not been replaced after recent maintenance; the French Bureau for Aircraft Accident Investigation (BEA) concluded that this did not contribute to the accident.[7][BEA 4] The wind at the airport was light and variable that day, and was reported to the cockpit crew as an eight knot tailwind as they lined up on runway 26R.[8]

Five minutes before the Concorde departed, a Continental Airlines McDonnell Douglas DC-10 took off from the same runway for Newark Liberty International Airport and lost a titanium alloy strip that was part of the engine cowl, identified as a wear strip about 435 millimetres (17.1 in) long, 29 to 34 millimetres (1.1 to 1.3 in) wide, and 1.4 millimetres (0.055 in) thick.[BEA 5][9] The Concorde ran over this piece of debris during its take-off run, cutting a tyre and sending a large chunk of tyre debris (4.5 kilograms or 9.9 pounds) into the underside of the aircraft's wing at an estimated speed of 140 metres per second (310 mph).[10] It did not directly puncture any of the fuel tanks, but it sent out a pressure shockwave that ruptured the number 5 fuel tank at the weakest point, just above the undercarriage. Leaking fuel gushing out from the bottom of the wing was most likely ignited either by an electric arc in the landing gear bay (debris cutting the landing gear wire) or through contact with hot parts of the engine.[BEA 6] Engines 1 and 2 both surged and lost all power, then engine 1 slowly recovered over the next few seconds.[BEA 7] A large plume of flame developed, and the flight engineer shut down engine 2 in response to a fire warning and the captain's command.[BEA 8]

Air traffic controller Gilles Logelin noticed the flames before the Concorde was airborne and informed the flight crew.[BEA 9] The aircraft had passed V1 speed so the crew continued the takeoff, but the plane did not gain enough airspeed with the three remaining engines because damage to the landing gear bay door prevented the retraction of the undercarriage.[BEA 10] The aircraft was unable to climb or accelerate, and its speed decayed during the course of its brief flight.[11] The fire caused damage to the port wing and it began to disintegrate, melted by the extremely high temperatures. Engine number 1 surged again, but this time failed to recover, and the starboard wing lifted from the asymmetrical thrust, banking the aircraft to over 100 degrees. The crew reduced the power on engines three and four in an attempt to level the aircraft, but they lost control due to falling speed and the aircraft stalled, crashing into the Hôtelissimo Les Relais Bleus Hotel.[2][12][13][14] The hotel is near the airport and adjacent to an intersection known as La Patte d'Oie de Gonesse (the Goose Foot of Gonesse)[15] for its radiating roads D902 and D317.

The crew was trying to divert to nearby Paris–Le Bourget Airport, but accident investigators stated that a safe landing would have been highly unlikely, given the aircraft's flight path. The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded[16] the last intelligible words in the cockpit (translated into English):

- Co-pilot: "Le Bourget, Le Bourget."

- Pilot: "Too late (unclear)."

- Control tower: "Fire service leader, correction, the Concorde is returning to runway zero nine in the opposite direction."

- Pilot: "No time, no (unclear)."

- Co-pilot: "Negative, we're trying Le Bourget" (four switching sounds).

- Co-pilot: "No (unclear)."

Fatalities

All the passengers and crew, and four employees of the Hotelissimo hotel, were killed in the crash.[17][18] Most of the passengers were German tourists en route to New York for a cruise.[17][18][19] The cockpit crew consisted of pilot Captain Christian Marty, 54, First Officer Jean Marcot, 50, and Flight Engineer Gilles Jardinaud, 58.[20][BEA 11]

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Ground | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | 1 | |

| 2 | - | - | 2 | |

| - | 8 | - | 8 | |

| 96 | 1 | - | 97 | |

| 1 | - | - | 1 | |

| - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| - | - | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 100 | 9 | 4 | 113 |

Concorde grounded

Until the crash of Air France Flight 4590 in 2000, Concorde had been considered among the world's safest planes.[21] The crash of the Concorde contributed to the end of the aircraft's career.[22]

A few days after the crash, all Concordes were grounded, pending an investigation into the cause of the crash and possible remedies.[23]

Air France's Concorde operation had been a money-losing venture, but it is claimed that the aeroplane had been kept in service as a matter of national pride;[24] British Airways claimed to make a profit on its Concorde operations.[25][26] According to Jock Lowe, a Concorde pilot, up until the crash of Air France Flight 4590 at Paris, the British Airways Concorde operation made a net average profit of about £30m a year.[27] Commercial service was resumed in November 2001 after a £17m safety improvement service, until the remaining aircraft were retired in 2003.[27][28]

Accident investigation

The official investigation was conducted by France's accident investigation bureau, the BEA, and it was published on 16 January 2002.[29]

Conclusions

The investigators concluded that:

- The aircraft was overloaded by 810 kilograms (1,790 lb) above the maximum safe takeoff weight. Any effect on takeoff performance from this excess weight was negligible.[30]

- After reaching takeoff speed, the tyre of the number 2 wheel was cut by a metal strip (a wear strip) lying on the runway, which had fallen from the thrust reverser cowl door of the number 3 engine of a Continental Airlines DC-10 that had taken off from the same runway five minutes previously.[31][32] This wear strip had been replaced at Tel Aviv, Israel, during a C check on 11 June 2000, and then again at Houston, Texas, on 9 July 2000. The strip installed in Houston had been neither manufactured nor installed in accordance with the procedures as defined by the manufacturer.[BEA 12]

- The aircraft was airworthy and the crew were qualified. The landing gear that later failed to retract had not shown serious problems in the past. Despite the crew's being trained and certified, no plan existed for the simultaneous failure of two engines on the runway, as it was considered highly unlikely.

- Aborting the takeoff would have led to a high-speed runway excursion and collapse of the landing gear, which also would have caused the aircraft to crash.

- While two of the engines had problems and one of them was shut down, the damage to the plane's structure was so severe that the crash would have been inevitable, even with the engines operating normally.

Previous tyre incidents

.jpg)

In November 1981, the American National Transportation Safety Board sent a letter of concern to the French BEA that included safety recommendations for Concorde. This communiqué was the result of the NTSB's investigations of four Air France Concorde incidents during a 20-month period from July 1979 to February 1981. The NTSB described those incidents as "potentially catastrophic," because they were caused by blown tyres during takeoff. During its 27 years in service, Concorde had about 70 tyre- or wheel-related incidents, 7 of which caused serious damage to the aircraft or were potentially catastrophic.[34]

- 13 June 1979: The number 5 and 6 tyres blew out during a takeoff from Washington Dulles International Airport. Fragments thrown from the tyres and rims damaged number 2 engine, punctured three fuel tanks, severed several hydraulic lines and electrical wires, and tore a large hole on the top of the wing over the wheel well area.

- 21 July 1979: Another blown tyre incident during takeoff from Dulles Airport. After that second incident the "French director general of civil aviation issued an air worthiness directive and Air France issued a Technical Information Update, each calling for revised procedures. These included required inspection of each wheel and tyre for condition, pressure and temperature prior to each takeoff. In addition, crews were advised that landing gear should not be raised when a wheel/tyre problem is suspected."

- August 1981: British Airways (BA) plane taking off from New York suffered a blow-out, damaging landing gear door, engine and fuel tank.[34]

- November 1985: Tyre burst on a BA plane leaving Heathrow, causing damage to the landing gear door and fuel tank. Two engines were damaged as a result of the accident.[34]

- January 1988: BA plane leaving Heathrow lost 10 bolts from its landing gear wheel. A fuel tank was punctured.[34]

- July 1993: Tyre burst on a BA plane during landing at Heathrow, causing substantial ingestion damage to the number 3 engine, damaging the landing gear and wing, and puncturing an empty fuel tank.[35]

- October 1993: Tyre burst on a BA plane during taxi at Heathrow, puncturing wing, damaging fuel tanks and causing a major fuel leak.[36]

Because it is a tailless delta-wing aircraft, Concorde could not use the normal flaps or slats to assist takeoff and landing, and required a significantly higher air and tyre speed during the takeoff roll than an average airliner. That higher speed increased the risk of tyre explosion during takeoff. When the tyres did explode, much greater kinetic energy was carried by the resulting fragments, increasing the risk of serious damage to the aircraft.

Modifications and revival

The accident led to modifications being made to Concorde, including more secure electrical controls, Kevlar lining to the fuel tanks, and specially developed, burst-resistant tyres.[37]

The crash of the Air France Concorde nonetheless proved to be the beginning of the end for the type.[38] Just before service resumed, the 11 September attacks took place, resulting in a marked drop in passenger numbers, and contributing to the eventual end of Concorde flights.[39] Air France stopped flights in May 2003, and British Airways ended its Concorde flights in October 2003.[40]

In June 2010, two groups attempted, unsuccessfully, to revive Concorde for "Heritage" flights in time for the 2012 Olympics. The British Save Concorde Group, SCG, and French group Olympus 593 were attempting to get four Rolls-Royce Olympus engines at Le Bourget Air and Space Museum.[41]

Criminal investigation

French authorities began a criminal investigation of Continental Airlines, whose plane dropped the debris on the runway, in March 2005,[42] and that September, Henri Perrier, the former chief engineer of the Concorde division at Aérospatiale at the time of the first test flight in 1969 and the programme director in the 1980s and early 1990s, was placed under formal investigation.[43]

In March 2008, Bernard Farret, a deputy prosecutor in Pontoise, outside Paris, asked judges to bring manslaughter charges against Continental Airlines and two of its employees – John Taylor, the mechanic who replaced the wear strip on the DC-10, and his manager Stanley Ford – alleging negligence in the way the repair was carried out.[44] Continental denied the charges,[45] and claimed in court that it was being used as a scapegoat by the BEA. The airline suggested that the Concorde "was already on fire when its wheels hit the titanium strip, and that around 20 first-hand witnesses had confirmed that the plane seemed to be on fire immediately after it began its take-off roll".[46][47]

At the same time charges were laid against Henri Perrier, head of the Concorde program at Aérospatiale, Jacques Hérubel, Concorde's chief engineer, and Claude Frantzen, head of DGAC, the French airline regulator.[44][48][49] It was alleged that Perrier, Hérubel and Frantzen knew that the plane's fuel tanks could be susceptible to damage from foreign objects, but nonetheless allowed it to fly.[50]

The trial ran in a Parisian court from February to December 2010. Continental Airlines was found criminally responsible for the disaster. It was fined €200,000 ($271,628) and ordered to pay Air France €1 million. Taylor was given a 15-month suspended sentence, while Ford, Perrier, Hérubel and Frantzen were cleared of all charges. The court ruled that the crash resulted from a piece of metal from a Continental jet that was left on the runway; the object punctured a tyre on the Concorde and then ruptured a fuel tank.[51][52][53] The convictions were overturned by a French appeals court in November 2012, thereby clearing Continental and Taylor of criminal responsibility.[52]

The Parisian court also ruled that Continental would have to pay 70% of any compensation claims. As Air France has paid out €100 million to the families of the victims, Continental could be made to pay its share of that compensation payout. The French appeals court, while overturning the criminal rulings by the Parisian court, affirmed the civil ruling and left Continental liable for the compensation claims.[52]

Alternative theories

British investigators and former French Concorde pilots looked at two factors that the BEA found to be of negligible consequence: an unbalanced weight distribution in the fuel tanks and loose landing gear. They came to the conclusion that the Concorde veered off course on the runway, which reduced takeoff speed below the crucial minimum. John Hutchinson, who had served as a Concorde captain for 15 years with British Airways, accused Air France of negligence.[20][54][55]

The Concorde had veered towards an Air France Boeing 747 carrying then-French President Jacques Chirac who was returning from the 26th G8 summit meeting in Okinawa, Japan,[5][56] which was much further down the runway than the Concorde's usual takeoff point; only then did it strike the metal strip from the DC-10.[20]

The Concorde was missing the spacer from the left main landing gear beam. This compromised the alignment of the landing gear and the wobbling beam and gears allowing three degrees of movement possible in any direction. The uneven load on the left leg's three remaining tyres skewed the landing gear, with the scuff marks of four tyres on the runway showing that the plane was veering to the left.[7] Air France found out that its maintenance staff had not replaced or renewed the spacer, which was found in a workshop after the crash.[46]

Legacy

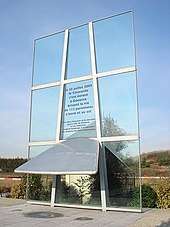

A monument in honour of the crash victims was established at Gonesse. The Gonesse monument consists of a piece of transparent glass with a piece of an aircraft wing jutting through.[57] Another monument, a 6,000-square-metre (65,000 sq ft) memorial topiary in the shape of a Concorde, was established in 2006 at Mitry-Mory, just south of Charles de Gaulle Airport.[58][59]

In popular culture

- The timeline and causes of the crash were profiled in the premiere episode of the National Geographic documentary series Seconds From Disaster.[60]

- NBC aired a Dateline NBC documentary on the crash, its causes, and its legacy on 22 February 2009.[61]

- Channel 4 and Discovery Channel Canada aired a documentary called Concorde's Last Flight.[62]

- Smithsonian Channel aired a 90-minute documentary [63] in 2010.

- The aircraft that crashed had previously been used in the making of the movie The Concorde ... Airport '79.[64]

- The accident and subsequent investigation were featured in the 7th episode during Season 14 of documentary series Mayday (also known as Air Crash Investigation) titled "Concorde: Up In Flames", first broadcast in January 2015.[65]

References

- ↑ Operator History

- 1 2 "Concorde Crash", The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "'Black boxes' recovered at Concorde crash site." CNN. 25 July 2000. Retrieved on 3 June 2009.

- ↑ BEA report, Page 159 "14h40m01s… it can be deduced that, for the crew, the aircraft weight at which the takeoff was commenced was 185,880 kg, for a MTOW of 185,070 kg".

- 1 2 3 "Concorde: For the Want of a Spacer". Iasa.com.au. 24 June 2001. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- 1 2 Brookes, Andrew, Destination Disaster, page 22, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-2862-1

- 1 2 Brookes, Andrew, Destination Disaster, page 19, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-2862-1

- ↑ BEA report, pp 17, 170.

- ↑ "Metal Part Maybe Came From Continental Jet". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ BEA report, Section 1.16.7.2.1.4 "Possible Energy Sources " (page 115).

- ↑ BEA preliminary report, pp.33-37

- ↑ "Concorde crash kills 113". BBC News. 25 July 2000.

- ↑ The damaged hotel and the scorched field show the impact of the crash, CBS News

- ↑ French police and rescue service workers inspect the debris of the hotel and the crashed jet., CBS News

- ↑ "Riding High: Auto Makers Jack Up the Car Seat; Finding Your Ideal 'H-Point'". LaDepeche.fr. 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "ANNEXE 2 Transcription de l'enregistreur phonique". BEA. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- 1 2 "2000: Concorde crash kills 113". BBC. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- 1 2 "What Went Wrong". Newsweek. 13 March 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mori to send messages to Chirac, Schroeder over Concorde." The Free Library. 26 July 2000. Retrieved on 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 Rose, David (13 May 2001). "Concorde: The unanswered questions". The Guardian. The Observer. London. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ↑ Ruppe, David. "Concorde's Stellar Safety Record". abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Caption to image #16 of set."

- ↑ Lichfield, John (18 October 2010). "Air France grounds Concorde until cause of crash is known". The Independent. London. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ Suzanne Scotchmer, Innovation and Incentives, MIT Press, 2004, p. 55.

- ↑ "The Concorde belies those who foresaw its extinction". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 26 January 1986.

- ↑ Arnold, James (10 October 2003). "Why economists don't fly Concorde". BBC News.

- 1 2 Westcott, Richard. "Could Concorde ever fly again? No, says British Airways". bbc.com. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ↑ "Concorde grounded for good". BBC News. 10 April 2003.

- ↑ "Press release, 16 January 2002 Issue of the final report into the Concorde accident on 25 July 2000". BEA. 16 January 2012. Archived from the original (English edition) on 6 January 2016.

- ↑ BEA report, p.159.

- ↑ BEA report Section 1.16.6, p102 "Metallic Strip found on the Runway".

- ↑ "'Poor repair' to DC-10 was cause of Concorde crash". Flight Global. 24 October 2000. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "N13067 Continental Air Lines McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 – cn 47866 / 149". Planespotters.net. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Jon Henley (17 August 2000). "Concorde crash 'a disaster waiting to happen'". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Air Accidents Investigation Branch (1993). "AAIB Bulletin No: 11/93" (PDF). Cabinet Office. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ↑ Air Accidents Investigation Branch (1994). "AAIB Bulletin No: 3/94" (PDF). Cabinet Office. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "New improved Concorde cleared for take-off". New Scientist. 6 September 2001. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Perception of Risk in the Wake of the Concorde Accident", Issue 14, Airsafe Journal, Revised 6 January 2001.

- ↑ "LATEST NEWS Archive". ConcordeSST.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Lawless, Jill (26 October 2003). "Final Concorde flight lands at Heathrow". Washington Post. Associated Press.

- ↑ "Iconic Concorde Could Return for 2012 Olympics Archived 10 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine."

- ↑ "Judge places Continental under investigation in Concorde crash". USA Today. 10 March 2005. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

A French magistrate on Thursday opened a formal investigation of Continental Airlines for manslaughter for the suspected role played by one of its jets in the July 2000 crash of the supersonic Concorde that killed 113 people. Investigating judge Christophe Regnard placed Continental under investigation—a step short of being formally charged—for manslaughter and involuntary injury, judicial officials said.

- ↑ "Ex-Concorde head quizzed on crash". BBC News. 27 September 2005. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- 1 2 "Prosecutor seeks Concorde charges". BBC News. 12 March 2008. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ "Continental denies responsibility for crash as Concorde trial begins". Deutsche Welle. 2 March 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Concorde crash remains unresolved 10 years later". digitaljournal.com. 25 July 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "Concorde crash manslaughter trial begins in France". BBC News. 2 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Bremner, Charles (12 March 2008). "Continental Airlines faces manslaughter charges over Paris Concorde crash". The Times. London.

- ↑ "Five to face Concorde crash trial". BBC News. 3 July 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

The five accused are: John Taylor, the Continental mechanic who allegedly fitted the metal strip to the DC-10, and Stanley Ford, a maintenance official from the airline; Henri Perrier, a former head of the Concorde division at Aerospatiale, now part of the aerospace company EADS, and Concorde's former chief engineer Jacques Herubel; Claude Frantzen, a former member of France's civil aviation watchdog

- ↑ Clark, Nicola (1 February 2010). "Trial to Open in Concorde Disaster". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ Fraser, Christian (6 December 2010). "Continental responsible for Concorde crash in 2000". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Concorde crash: Continental Airlines cleared by France court". BBC News. 29 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ "Paris Court Finds Continental Responsible for Concorde Crash". Voice of America. 6 December 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ "Concorde: For the Want of a Spacer". iasa.com.au. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "Untold Story of the Concorde Disaster". askthepilot.com. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ Brookes, Andrew, Destination Disaster, page 14, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-2862-1

- ↑ Families mark 10 years since Concorde crash. Associated Press at the USA Today. 25 July 2010. Retrieved on 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Un mémorial pour les victimes du crash du Concorde La zone commerciale s'agrandit Participez au concours Pep's Star La mairie propose de parler de tout Débattez du logement avec Marie-Noëlle Lienemann. Le Parisien. 25 April 2006. Retrieved on 27 September 2013.

- ↑ "Mémorial AF4590". club-concorde.org. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "Seconds from Disaster, Schedule, Video, Photos, Facts and More". National Geographic Channel. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ Greenberg, Peter (1 February 2010). "What brought down the Concorde?". Dateline NBC. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ Bramson, Dara (1 July 2015). "Where Is Today's Supersonic Jet?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Concorde: Flying Supersonic". Smithsonian Channel. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "The Concorde SST Web Site: History of the aircraft that would become Air France Flight 4590". Concordesst.com. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ National Geographic Channel (2016), Air Crash Investigation, retrieved 29 October 2016.

BEA

Accident on 25 July 2000 at La Patte d'Oie in Gonesse (95) to the Concorde registered F-BTSC operated by Air France (REPORT translation f-sc000725a) (PDF), BEA

- ↑ Page 32: "The maximum structural weight on takeoff being 185,070 kg, it appears that the aircraft was slightly overloaded on takeoff".

- ↑ Page 159.

- ↑ Section 1.16.7.3 "The Fuel in Tank 5" (page 118): "Taking into account these calculations, we may consider that the quantity of fuel in tank 5 was practically that which was loaded on the apron, which represents around 94% of the total volume of the tank".

- ↑ Page 155: "In conclusion, nothing in the research undertaken indicates that the absence of the spacer contributed in any way to the accident on 25 July 2000"

- ↑ Section 1.16.6.4 "Examination of the Wear Strip" (page 107)

- ↑ Section 1.16.8.3 "Ignition and Propagation of the Flame" (pages 120–123).

- ↑ Section 1.1 "History of the Flight" (page 17).

- ↑ Section 2.2 "Crew Actions" (page 166): "The exceptional environment described above quite naturally led the FE to ask to shut down the engine. This was immediately confirmed by the Captain's calling for the engine fire procedure".

- ↑ Section 1.1 "History of the Flight" (page 17).

- ↑ Section 1.16.10 "Origin of the Non-retraction of the Landing Gear" (pages 134–135).

- ↑ Section 1.5.1 "Flight Crew" (pages 18-20)

- ↑ Sections 1.16.6.2 "Manufacturer’s Documentation" and 1.16.6.3 "Maintenance on N 13067" (pages 105–107), and section 2.6 "Maintenance at Continental Airlines" (page 171) and section 3.1 "Findings" (page 174).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Air France Flight 4590. |

- Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile

- "Accident on 25 July 2000 at "La Patte d'oie" at Gonesse."

- "Accident survenu le 25 juillet 2000 au lieu-dit "La Patte d'oie" à Gonesse."

- Preliminary report (in French) (PDF, Archive), published 1 September 2000.

- Interim report (in French) (PDF, Archive), published 15 December 2000.

- Interim report 2 (in French) (PDF, Archive), published 23 July 2001.

- Final report (in French) (PDF, Archive), published 16 January 2002 – the French version is the report of record.

- PlaneCrashInfo.Com – Data Entry on Flight 4590

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- The Observer – this article mentions other contributing factors

- Disaster, CBS News

- CVR transcript

- All 109 Aboard Dead in Concorde Crash into Hotel Near Paris; 4 On Ground Dead – CNN

- Safety Recommendation(s) (PDF), Washington, DC: National Transportation Safety Board, 9 November 1981, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2009

- "Concorde Incidents & Fatal Accident". Airguideonline.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2010.