Ad orientem

Ad orientem is a Latin phrase meaning "to the east" and is used in many contexts. In the Vulgate, which is the Catholic Church's official Latin translation of the Bible, it appears 36 times, with varied contexts. However, in the contexts both of Christian prayer and of Christian liturgy it is employed with specific meanings that will be examined in this article.

Orientation in prayer

The earliest known use of the exact Latin phrase ad orientem[1] to describe the Christian practice of facing east when praying is in Augustine's De Sermone Domini in Monte, probably of AD 393.[2] The equivalent Latin phrase, ad orientis regionem (to the region of the east), was used two centuries earlier by Tertullian in his Apologeticus (AD 197) to indicate the practice.[3]

Early evidence of Christian praying towards the east

Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 220) says that, because Christians faced towards the east at prayer, some non-Christians thought they worshipped the sun.[4]

Clement of Alexandria ( c. 150 – c. 215) says: "Since the dawn is an image of the day of birth, and from that point the light which has shone forth at first from the darkness increases, there has also dawned on those involved in darkness a day of the knowledge of truth. In correspondence with the manner of the sun's rising, prayers are made looking towards the sunrise in the east."[5]

Origen (c. 185 – 253) says: "The fact that [...] of all the quarters of the heavens, the east is the only direction we turn to when we pour out prayer, the reasons for this, I think, are not easily discovered by anyone."[6]

Later on, Fathers of the Church such as John of Damascus advanced mystical reasons for the custom.[7]

Origin of the practice

In 1971, Georg Kretschmar proposed a connection between the Christian custom of praying towards the east and a practice of the earliest Christians in Jerusalem of praying towards the Mount of Olives, situated to the east of the city and seen as the locus of key eschatological events and of the Second Coming of Christ. In this view, the localization of the Second Coming on the Mount of Olives was abandoned after the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 and the eastward direction of Christian prayer became general. The theory of Christian prayer towards the Mount of Olives has been rejected by Stefan Heid, but is defended by Uwe Michael Lang. On the other hand, Lang says that it was at that time a practice even among many Jews to pray eastward.[8]

Paul F. Bradshaw says that the Christians adopted the eastward orientation when praying, as did the Jewish sects of the Essenes and the Therapeutae, for whom "the eastward prayer had acquired an eschatological dimension, the 'fine bright day' for which the Therapeutae prayed being apparently the messianic age and the Essene prayer towards the sun 'as though beseeching him to rise' being a petition for the coming of the priestly Messiah."[9]

The primitive Church had no knowledge of the origin of the practice. Origen says: "The reasons for this, I think, are not easily discovered by anyone."[6] Although the general custom among Jews was to pray towards the temple in Jerusalem, Clement of Alexandria, Origen's older contemporary, says that the custom of praying eastward was general even among non-Christians: "In correspondence with the manner of the sun's rising, prayers are made looking towards the sunrise in the east. Whence also the most ancient temples looked towards the west, that people might be taught to turn to the east when facing the images."[5]

Statements by later ecclesiastics

In the ninth century, Saint John of Damascus, a Doctor of the Church, wrote:[7]

It is not without reason or by chance that we worship towards the East. But seeing that we are composed of a visible and an invisible nature, that is to say, of a nature partly of spirit and partly of sense, we render also a twofold worship to the Creator; just as we sing both with our spirit and our bodily lips, and are baptized with both water and Spirit, and are united with the Lord in a twofold manner, being sharers in the Mysteries and in the grace of the Spirit. Since, therefore, God is spiritual light, and Christ is called in the Scriptures Sun of Righteousness and Dayspring, the East is the direction that must be assigned to His worship. For everything good must be assigned to Him from Whom every good thing arises. Indeed the divine David also says, Sing unto God, ye kingdoms of the earth: O sing praises unto the Lord: to Him that rideth upon the Heavens of heavens towards the East. Moreover the Scripture also says, And God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there He put the man whom He had formed: and when he had transgressed His command He expelled him and made him to dwell over against the delights of Paradise, which clearly is the West. So, then, we worship God seeking and striving after our old fatherland. Moreover the tent of Moses had its veil and mercy seat towards the East. Also the tribe of Judah as the most precious pitched their camp on the East. Also in the celebrated temple of Solomon, the Gate of the Lord was placed eastward. Moreover Christ, when He hung on the Cross, had His face turned towards the West, and so we worship, striving after Him. And when He was received again into Heaven He was borne towards the East, and thus His apostles worship Him, and thus He will come again in the way in which they beheld Him going towards Heaven; as the Lord Himself said, As the lightning cometh out of the East and shineth even unto the West, so also shall the coming of the Son of Man be. So, then, in expectation of His coming we worship towards the East. But this tradition of the apostles is unwritten. For much that has been handed down to us by tradition is unwritten.[7]

Timothy I, an eighth-century patriarch of the Church of the East declared:[8]

He [Christ] has taught us all the economy of the Christian religion: baptism, laws, ordinances, prayers, worship in the direction of the east, and the sacrifice that we offer. All these things He practiced in His person and taught us to practise ourselves.[8]

Moses Bar-Kepha, a ninth-century bishop of the Syriac Orthodox Church called praying towards the east one of the mysteries of the Church.[8]

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who later became Pope Benedict XVI, described the eastward orientation as linked with the "cosmic sign of the rising sun which symbolizes the universality of God."[10]

History and present-day usage

Outside of Rome, it was an ancient custom for most churches to be built with the entrance at the west end and for priest and people to face eastward to the place of the rising sun.[11]

On the history of the custom of constructing many but not all churches in this way, see Orientation of churches.

Among the exceptions was the original Constantinian Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which had the altar in the west end.[12][13]

Members of the Pentecostal Apostolic Faith Mission continue to pray facing east, believing that it "is the direction from which Jesus Christ will come when he returns".[14]

It is common for members of Oriental Orthodox Churches to pray privately in their homes facing eastward; when a priest visits one's home, he usually asks where the east is before he leads a family in prayer.

Byzantine Orthodox also face east when praying.[15]

On the other hand, there are some small Christian groups that consider praying towards the east "an abomination".[16]

Liturgical orientation

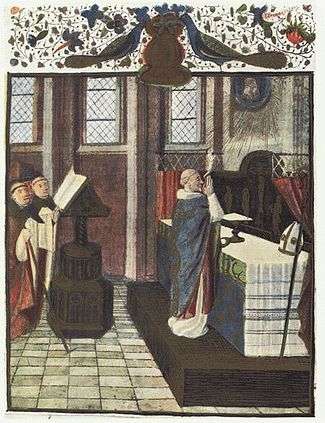

Ad orientem is commonly used today to describe a particular orientation of a priest in Christian liturgy, facing the apse or wall behind the altar, with priest and people looking in the same direction, as opposed to the versus populum orientation, in which the priest faces the congregation. In this use, the phrase is not necessarily related to the geographical direction in which the priest is looking and is employed even if he is not facing to the east or even has his back to the east.

The Tridentine Roman Missal, even in its last edition, which was published in 1962, instead uses ad orientem to mean "facing the people", presumably in a church that has the altar at the west end, although it does not specify this: "Si altare sit ad orientem, versus populum, celebrans versa facie ad populum, non vertit humeros ad altare, cum dicturus est Dóminus vobiscum, Oráte, fratres, Ite, missa est, vel daturus benedictionem ..." (If the altar is ad orientem, towards the people, the celebrant, facing the people, does not turn his back to the altar when about to say Dominus vobiscum ["The Lord be with you"], Orate, fratres [the introduction to the prayer over the offerings of bread and wine], and Ite, missa est [the dismissal at the conclusion of the Mass], or about to give the blessing ...)[17]

History and practice

In early Christianity, the practice of praying towards the east did not result in uniformity in the orientation of the buildings in which Christians worshipped and did not mean that the priest necessarily faced away from the congregation, the meaning today commonly attached to the phrase ad orientem. The earliest churches in Rome had a façade to the east and an apse with the altar to the west; the priest celebrating Mass stood behind the altar, facing east and so towards the people.[18][19] According to Louis Bouyer, not only the priest but also the congregation faced east at prayer, a view strongly criticized on the grounds of the unlikelihood that, in churches where the altar was to the west, they would turn their backs on the altar (and the priest) at the celebration of the Eucharist. The view prevails therefore that the priest, facing east, would celebrate ad populum in some churches, in others not, in accordance with the churches' architecture.[20]

It was in the 8th or 9th century that the position whereby the priest faced the apse, not the people, when celebrating Mass was adopted in the basilicas of Rome.[21] This usage was introduced from the Frankish Empire and later became almost universal in the West.[22] However, the Tridentine Roman Missal continued to recognize the possibility of celebrating Mass "versus populum" (facing the people),[23] and in several churches in Rome, it was physically impossible, even before the twentieth-century liturgical reforms, for the priest to celebrate Mass facing away from the people, because of the presence, immediately in front of the altar, of the "confession" (Latin: confessio), an area sunk below floor level to enable people to come close to the tomb of the saint buried beneath the altar.

Anglican Bishop Colin Buchanan writes that there "is reason to think that in the first millennium of the church in Western Europe, the president of the eucharist regularly faced across the eucharistic table toward the ecclesiastical west. Somewhere between the 10th and 12th centuries, a change occurred in which the table itself was moved to be fixed against the east wall, and the president stood before it, facing east, with his back to the people."[24] This change, according to Buchanan, "was possibly precipitated by the coming of tabernacles for reservation, which were ideally both to occupy a central position and also to be fixed to the east wall without the president turning his back to them."[24]

In 7th century England, it is said, Catholic churches were built so that on the very feast day of the saint in whose honor they were named, Mass could be offered on an altar while directly facing the rising sun.[25] However, various surveys of old English churches found no evidence of any such general practice.[26][27][28]

The present-day General Instruction of the Roman Missal does not forbid the ad orientem position for the priest when saying Mass and only requires that in new or renovated churches the facing-the-people orientation be made possible: "The altar should be built separate from the wall, in such a way that it is possible to walk around it easily and that Mass can be celebrated at it facing the people, which is desirable wherever possible."[29] As in some ancient churches the ad orientem position was physically impossible, so today there are churches and chapels in which it is physically impossible for the priest to face the people throughout the Mass. A letter of 25 September 2000 from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments treats the phrase "which is desirable wherever possible" as referring to the requirement that altars be built separate from the wall, not to the celebration of Mass facing the people, while "it reaffirms that the position toward the assembly seems more convenient inasmuch as it makes communication easier ... without excluding, however, the other possibility."[30] On 13 January 2008, Pope Benedict XVI publicly celebrated Mass in the Sistine Chapel at its altar, which is attached to the west wall.[31] He later celebrated Mass at the same altar in the Sistine Chapel annually for the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord. His celebration of Mass in the Pauline Chapel in the Apostolic Palace on 1 December 2009 was reported to be the first time he publicly celebrated Mass ad orientem on a freestanding altar.[32] In reality, earlier that year the chapel had been remodelled, with "the previous altar back in its place, although still a short distance from the tabernacle, restoring the celebration of all 'facing the Lord'."[33] On 15 April 2010 he again celebrated Mass in the same way in the same chapel and with the same group.[34] The practice of saying Mass at the altar attached to the west wall of the Sistine Chapel on the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord was continued by Pope Francis, when he celebrated the feast for the first time as Supreme Pontiff on 12 January 2014. Although neither before nor after the 20th-century revision of the Roman Rite did liturgical norms impose either orientation, the distinction became so linked with traditionalist discussion that it was considered journalistically worthy of remark that Pope Francis celebrated Mass ad orientem [35] at an altar at which only this orientation was possible.[36]

In a conference in London on 5 July 2016, Cardinal Robert Sarah, Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, encouraged priests to adopt the ad orientem position from the first Sunday in Advent at the end of that year. However, the Vatican soon clarified that this was a personal view of the cardinal and that no official directives would be issued to change the prevailing practice of celebrating versus populum.[37]

Church of England

With the English Reformation, the Church of England directed that the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist be celebrated at a communion table placed lengthwise in the chancel or in the body of the church, with the priest standing on the north side of the holy table, facing south. Turning to the east continued to be observed at certain points of the Anglican liturgy, including the praying of the Gloria Patri, Gloria in Excelsis and ecumenical creeds in that direction.[38] Archbishop Laud, under direction from Charles I of England, encouraged a return to the use of the altar at the east end, but in obedience to the rubric in the Book of Common Prayer the priest stood at the north end of the altar. In the middle of the 19th century, the Oxford Movement gave rise to a return to the eastward-facing position, and use of the versus populum position appeared in the second half of the 20th century.[39]

However, over "the course of the last forty years or so, a great many of those altars have either been removed and pulled out away from the wall or replaced by the kind of freestanding table-like altar", in "response to the popular sentiment that the priest ought not turn his back to the people during the service; the perception was that this represented an insult to the laity and their centrality in worship. Thus developed today’s widespread practice in which the clergy stand behind the altar facing the people."[40]

See also

References

- ↑ Thunø, Erik (12 December 2017). The Apse Mosaic in Early Medieval Rome. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9781107069909.

In the West, the tradition is first witnessed by Augustine: 'When we stand at prayer, we turn to the east (ad orientem), whence the heaven rises.'

- ↑ "Cum ad orationem stamus, ad orientem convertimur, unde caelum surgit" (Augustini De Sermone Domini in Monte, II, 5, 18; translation: "When we stand at prayer, we turn to the east, whence the heaven rises" (Augustine, On the Sermon on the Mount, Book II, Chapter 5, 18).

- ↑ "Inde suspicio [solem credere deum nostrum], quod innotuerit nos ad orientis regionem precari" (Tertulliani Apologeticum, XVI, 9); translation: "The idea [that the sun is our god] has no doubt originated from our being known to turn to the east in prayer" (Tertullian, Apology, chapter XVI).

- ↑ Tertuliano, Apologeticus, 16.9–10; translation

- 1 2 Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, book 7, chapter 7

- 1 2 "quod ex omnibus coeli plagis ad solam orientis partem conversi orationem fundimus, non facile cuiquam puto ratione compertum" (Origenis in Numeros homiliae, Homilia V, 1; translation

- 1 2 3 "Why We Pray Facing East". Orthodox Prayer. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Lang, Uwe Michael (2009). Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer. Ignatius Press. p. 37–38, 45, 57-58. ISBN 9781586173418. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Paul F. Bradshaw, Daily Prayer in the Early Church (Wipf and Stock, 2008), pp. 11, 38

- ↑ The Spirit of the Liturgy, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Ad Solem, 2006 p. 64

- ↑ Porteous, Julian (2010). After the Heart of God. Books.google.com. Taylor Trade. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-58979579-2. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ↑ D. Fairchild Ruggles, On Location: Heritage Cities and Sites (Springer 2011 ISBN 978-1-46141108-6), p. 134

- ↑ Lawrence Cunningham, John Reich, Lois Fichner-Rathus, Culture and Values: A Survey of the Humanities, Volume 1 |(Cengage Learning 2013 ISBN 978-1-13395244-2), pp. 208–210

- ↑ Farhadian, Charles E. (16 July 2007). Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9780802828538. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Why Do We Pray Facing East?

- ↑ Facing East to Pray Is an Abomination

- ↑ Ritus servandus in celebratione Missae, V, 3 (page LVII in the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal)

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "orientation"

- ↑ "When Christians in fourth-century Rome could first freely begin to build churches, they customarily located the sanctuary towards the west end of the building in imitation of the sanctuary of the Jerusalem Temple. Although in the days of the Jerusalem Temple the high priest indeed faced east when sacrificing on Yom Kippur, the sanctuary within which he stood was located at the west end of the Temple. The Christian replication of the layout and the orientation of the Jerusalem Temple helped to dramatize the eschatological meaning attached to the sacrificial death of Jesus the High Priest in the Epistle to the Hebrews" (The Biblical Roots of Church Orientation by Helen Dietz).

- ↑ Remery, Michel (2010-12-20). Mystery and Matter. Books.google.com. Brill. p. 179. ISBN 978-9-00418296-7. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "westward position"

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "eastward position"

- ↑ Ritus servandus in celebratione Missae, V, 3

- 1 2 Buchanan, Colin (27 February 2006). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. Scarecrow Press. p. 472. ISBN 9780810865068.

- ↑ Andrew Louth, "The Body in Western Catholic Christianity," in Religion and the Body, ed. by Sarah Coakley, (Cambridge, 2007) p. 120.

- ↑ "Ian Hinton, "Churches face East, don't they?" in British Archaeology". Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ↑ Jason R. Ali, Peter Cunich, "The orientation of churches: Some new evidence" in The Antiquaries Journal

- ↑ Peter G. Hoare and Caroline S. Sweet, "The orientation of early medieval churches in England" in Journal of Historical Geography 26, 2 (2000) 162–173 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "General Instruction of the Roman Missal". Usccb.org. p. 299.

- ↑ English translation of Letter of protocol number 2036/00/L and date 25 September 2000. This is also what is stated in the original text (in Latin) of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (2002), which reads, "Altare maius exstruatur a pariete seiunctum, ut facile circumiri et in eo celebratio versus populum peragi possit, quod expedit ubicumque possibile sit." As quod is a neuter pronoun, it cannot refer back to the feminine celebratio [versus populum] and mean that celebration facing the people expedit ubicumque possible sit ("is desirable wherever possible"), but must refer to the entirety of the preceding phrase about building the altar separate from the wall so to facilitate walking around it and celebrating Mass at it while facing the people. That the English translation of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 299 is misleading is the view of, for instance, Fr. John Zuhlsdorf and Fr. Timothy Johnson .

- ↑ Isabelle de Gaulmyn, Benedict XVI celebrated a Mass "back to the people" in La Croix, 15 January 2008 Archived October 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kollmorgen, Gregor (15 January 2008). "Pope Celebrates Ad Orientem in the Pauline Chapel". New Liturgical Movement.

- ↑ "Sandro Magister, "The Pauline Chapel Reopened for Worship. With Two New Features", 6 July 2009" (in Italian). Chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ↑ Kollmorgen, Gregor (15 April 2010). "Holy Father Celebrates Mass with the Pontifical Biblical Commission". New Liturgical Movement.

- ↑ Stanley, Tim (2013-11-01). "Pope Francis says Mass "ad orientem"". Blogs.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ↑ West, Ed (2011-05-03). "''Catholic Herald'', 3 May 2011: "First images of John Paul II's new tomb"". Catholicherald.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ↑ Catholic News Service, "Vatican rejects Cardinal Sarah's ad orientem appeal"

- ↑ Russell, Bruce (24 September 2006). "Gestures of Reverence in Anglican Worship". The Diocese of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

In subsequent centuries the practice was clearly understood as rooted in Scripture and tradition and survived the Reformation in the Church of England. According to Dearmer: The ancient custom of turning to the East, or rather to the altar, for the Gloria Patri and the Gloria in Excelsis survived through the slovenly times, and is now common amongst us. (The choir also turned to the altar for the intonation of the Te Deum, and again for its last verse.) We get a glimpse of the custom after the last revision [i.e. 1662] from a letter which Archdeacon Heweston wrote in 1686 to the great Bishop Wilson (then at his ordination as deacon), telling him to ‘turn towards the East whenever the Gloria Patri and the Creeds are rehearsing’: of this and other customs he says, ‘which thousands of good people of our Church practice at this day.’ The practice here mentioned of turning to the East for the Creeds was introduced by the Caroline divines, and has established itself firmly amongst us, though it is not embodied in a rubric at the last revision as were some of the other ceremonial additions of the Laudian school. It thus rests upon a common English custom three centuries old, and it is in every way an excellent practice. But it may well be doubted whether there is any reason for turning to the East to sing that ’Confession of our Christian Faith’ which is ‘commonly called the Creed of Saint Athanasius’… the proper use is to turn to the altar only for the Gloria Patri at its conclusion. [p. 198-199] It should be made clear that showing reverence to the altar or holy table, (historically Anglicans have used these terms interchangeably with varying emphasis over the centuries), when passing it, or in coming or going from the church etc. are indications of reverence for what occurs upon it, and not to be confused with turning to the East for the Creed, or when expressly addressing the Blessed Trinity in praise. This is admittedly slightly confusing, especially in churches which do not have an actual Eastward orientation. In such cases the direction of the church is presumed to be symbolically Eastward, and facing the direction of the principal altar is taken as East-facing, but Anglicans do not, as is sometimes supposed, face the altar for the Creed etc., rather it is the altar is aligned with our actual or symbolic orientation. The Hierurgia Anglicana records that the ancient practice of Eastward recitations were still retained at Manchester Cathedral in 1870, and Procter and Frere record that the custom at Salisbury, for recitation of the Nicene Creed only, “was for the choir to face the altar at the opening words, till they took up the signing, to turn to the altar again for the bowing at the Incarnatus, and again at the last clause to face the altar until the Offertory.” [p. 391] J. Wickham Legg observed : It will be noticed how persistent has been the custom in the Church of England of turning to the East at the Apostles’ Creed. Toward the end of the nineteenth century certain persons, hangers onto the High Church school, though unworthy of that honored name, discovered that the custom was only English, and they discontinued it in their persons.” However Legg points out that it was recorded in seventeenth century France and it would seem to have been rather more widely observed than the Anglo-papalists he decries could have known. This would seem to be another instance of the liturgical conservatism of the British Church preserving a distinctive and once more universal expression of popular devotion otherwise abandoned. Another instance of orientation was the now much rarer custom of turning to the East for the Doxology at the conclusion of the recitation of each Psalm, particularly by those in choir. This was the custom at Probus in Cornwall in the early years of the nineteenth century, as it was in rural North Devon long before the influence of Puseyism: “all the singing time they used to face West, staring at the gallery, with its faded green curtains; and then; when the Gloria came, they all turned ‘right about’ and faced Eastward.” [Legg, p. 180] ... Some evangelical Anglicans argue strongly against the Eastward position, yet as we have noted its use is documented in the earliest records of the Church. They especially oppose it for the celebrant during the Holy Communion because it seems to them to imply an unacceptable theology of priestly sacrifice. In doing so they neglect to notice the arbitrariness of the North position; the South side, for example, would offer an equally unimpeded view of the celebrant’s actions. The early Reformers, who were the advocates of the North position, had in mind the instructions given in Leviticus, that the priest shall sacrifice animal offerings ‘on the side of the altar northward’ [i: 11] and as such its use implies the exact opposite of what contemporary Evangelicals presume is intended.

- ↑ Heflig, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (2006). The Oxford Guide to the Book of Common Prayer. Oxford University Press. pp. 106–115. ISBN 9780199723898. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ Liles, Eric J. (2014). "The Altar". St. Paul's Episcopal Church. The Episcopal Church.

Many Episcopalians remember a time when the altars in most Episcopal churches were attached to the wall beyond the altar rail. The Celebrant at the Eucharist would turn to the altar and have his back – his back, never hers in those days – to the congregation during the Eucharistic Prayer and the consecration of the bread and wine. Over the course of the last forty years or so, a great many of those altars have either been removed and pulled out away from the wall or replaced by the kind of freestanding table-like altar we now use at St. Paul’s, Ivy. This was a response to the popular sentiment that the priest ought not turn his back to the people during the service; the perception was that this represented an insult to the laity and their centrality in worship. Thus developed today’s widespread practice in which the clergy stand behind the altar facing the people.