Active SETI

Active SETI (Active Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) is the attempt to send messages to intelligent extraterrestrial life. Active SETI messages are usually sent in the form of radio signals. Physical messages like that of the Pioneer plaque may also be considered an active SETI message. Active SETI is also known as METI (Messaging to Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence). The term METI was coined by Russian scientist Alexander Zaitsev, who denoted the clear-cut distinction between Active SETI and METI:[1][2]

The science known as SETI deals with searching for messages from aliens. METI deals with the creation and transmission of messages to aliens. Thus, SETI and METI proponents have quite different perspectives. SETI scientists are in a position to address only the local question “does Active SETI make sense?” In other words, would it be reasonable, for SETI success, to transmit with the object of attracting ETI’s attention? In contrast to Active SETI, METI pursues not a local and lucrative impulse, but a more global and unselfish one – to overcome the Great Silence in the Universe, bringing to our extraterrestrial neighbors the long-expected annunciation “You are not alone!”

In 2010, Douglas A. Vakoch of the SETI Institute addressed concerns about the validity of Active SETI alone as an experimental science by proposing the integration of Active SETI and Passive SETI programs to engage in a clearly articulated, ongoing, and evolving set of experiments to test various versions of the Zoo Hypothesis, including specific dates at which a first response to messages sent to particular stars could be expected.[3]

On 13 February 2015, scientists (including Douglas Vakoch, David Grinspoon, Seth Shostak, and David Brin) at an annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, discussed Active SETI and whether transmitting a message to possible intelligent extraterrestrials in the Cosmos was a good idea;[4][5] That same week, a statement was released, signed by many in the SETI community including Berkeley SETI Research Center director Andrew Siemion, advocating that a "worldwide scientific, political and humanitarian discussion must occur before any message is sent".[6] On 28 March 2015, an essay with a different point of view was written by Seth Shostak and published in The New York Times.[7]

Rationale for METI

In the paper Rationale for METI, transmission of the information into the Cosmos is treated as one of the pressing needs of an advanced civilization. This view is not universally accepted, and it does not agree to those who are against the transmission of interstellar radio messages, but at the same time are not against SETI searching. Such duality are called The SETI Paradox.

Radio message construction

The lack of an established communications protocol is a challenge for METI.

First of all, while trying to synthesize an Interstellar Radio Message (IRM), we should bear in mind that Extraterrestrials will first deal with a physical phenomenon and, only after that, perceive the information. At first, ET's receiving system will detect the radio signal; then, the issue of extraction of the received information and comprehension of the obtained message will arise. Therefore, above all, the Constructor of an IRM should be concerned about the ease of signal determination. In other words, the signal should have maximum openness, which is understood here as an antonym of the term security. This branch of signal synthesis can be named anticryptography.

To this end, in 2010, Michael W. Busch created a general-purpose binary language,[8] later used in the Lone Signal project[9] to transmit crowdsourced messages to extraterrestrial intelligence.[10] Busch developed the coding scheme and provided Rachel M. Reddick with a test message, in a blind test of decryption.[8] Reddick decoded the entire message after approximately twelve hours of work.[8] This was followed by an attempt to extend the syntax used in the Lone Signal hailing message to communicate in a way that, while neither mathematical nor strictly logical, was nonetheless understandable given the prior definition of terms and concepts in the hailing message.[11]

Also characteristics of the radio signal such as wavelength, type of polarization, and modulation have to be considered.

Over galactic distances, the interstellar medium induces some scintillation effects and artificial modulation of electromagnetic signals. This modulation is higher at lower frequencies and is a function of the sky direction. Over large distances, the depth of the modulation can exceed 100%, making any METI signal very difficult to decode.

Error correction

In METI research, it is implied that any message must have some redundancy, although the exact amount of redundancy and message formats are still in great dispute.

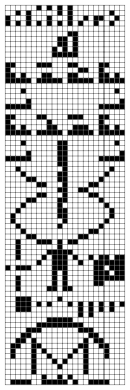

Using ideograms, instead of binary sequence, already offers some improvement against noise resistance. In faxlike transmissions, ideograms will be spread on many lines. This increases its resistance against short bursts of noise like radio frequency interference or interstellar scintillation.

One format approach proposed for interstellar messages was to use the product of two prime numbers to construct an image. Unfortunately, this method works only if all the bits are present. As an example, the message sent by Frank Drake from the Arecibo Observatory in 1974 did not have any feature to support mechanisms to cope with the inevitable noise degradation of the interstellar medium.

Error correction tolerance rates for previous METI messages

- Arecibo Message (1974) : 8.9% (one page)

- Evpatoria message (1999) : 44% (23 separate pages)

- Evpatoria message (2003) : 46% (one page, estimated)

Examples

The 1999 Cosmic Call transmission was far from being optimal (from our terrestrial point of view) as it was essentially a monochromatic signal spiced with a supplementary information. Additionally, the message had a very small modulation index overall, a condition not viewed as being optimal for interstellar communication.

- Over the 370,967 bits (46,371 bytes) sent, some 314,239 were “1” and 56,768 were “0”—5.54 times as many 1's as 0's.

- Since frequency shift keying modulation scheme was used, most of the time the signal was on the “0” frequency.

- In addition, “0” tended to be sent in long stretches (white lines in the message).

Realized projects

These projects have targeted stars between 17 and 69 light-years from the Earth. The exception is the Arecibo message, which targeted globular cluster M13, approximately 24,000 light-years away.

The first message to reach its destination will be RuBisCo Stars, which should reach Teegarden's star, a brown dwarf in 2021.

- The Morse Message (1962)[12]

- Arecibo message (1974)

- Cosmic Call 1 (1999)

- Teen Age Message (2001)

- Cosmic Call 2 (2003)

- Across the Universe (2008)

- A Message From Earth (2008)

- Hello From Earth (2009)

- RuBisCo Stars (2009)[13]

- Wow! Reply (2012) [14]

- Lone Signal (2013)

- A Simple Response to an Elemental Message (2016)

Transmissions

Stars to which messages were sent, are the following:[15][16][17][18][19]

| Name | Designation | Constellation | Date sent (YYYY-MM-DD) |

Arrival date (YYYY-MM-DD) |

Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Messier 13 | NGC 6205 | Hercules | 1974-11-16 | 27000~ | Arecibo Message |

| Altair | Alpha Aql | Aquila | 1983-08-15 | 2017 | Altair (Morimoto - Hirabayashi) Message [20] |

| Spica | Alpha Vir | Virgo | 1997-08 | 2247 | NASDA Cosmic-College |

| 16 Cyg A | HD 186408 | Cygnus | 1999-05-24 | 2069-11 | Cosmic Call 1 |

| 15 Sge | HD 190406 | Sagitta | 1999-06-30 | 2057-02 | |

| HD 178428 | 2067-10 | ||||

| Gl 777 | HD 190360 | Cygnus | 1999-07-01 | 2051-04 | |

| HD 197076 | Delphinus | 2001-08-29 | 2070-02 | Teen Age Message | |

| 47 UMa | HD 95128 | Ursa Major | 2001-09-03 | 2047-07 | |

| 37 Gem | HD 50692 | Gemini | 2057-12 | ||

| HD 126053 | Virgo | 2001-09 | 2059-01 | ||

| HD 76151 | Hydra | 2001-09-04 | 2057-05 | ||

| HD 193664 | Draco | 2059-01 | |||

| HIP 4872 | Cassiopeia | 2003-07-06 | 2036-04 | Cosmic Call 2 | |

| HD 245409 | Orion | 2040-08 | |||

| 55 Cnc | HD 75732 | Cancer | 2044-05 | ||

| HD 10307 | Andromeda | 2044-09 | |||

| 47 UMa | HD 95128 | Ursa Major | 2049-05 | ||

| Polaris | HIP 11767 | Ursa Minor | 2008-02-04 | 2439 | Across the Universe |

| Gliese 581 | HIP 74995 | Libra | 2008-10-09 | 2029 | A Message From Earth |

| 2009-08-28 | 2030 | Hello From Earth | |||

| GJ 83.1 | GJ 83.1 | Aries | 2009-11-07 | 2024 | RuBisCo Stars |

| Teegarden's Star | SO J025300.5+165258 | 2022 | |||

| Kappa1 Ceti | GJ 137 | Cetus | 2039 | ||

| HIP 34511 | Gemini | 2012-08-15 | 2163 | Wow! Reply | |

| 37 Gem | HD 50692 | 2069 | |||

| 55 Cnc | HD 75732 | Cancer | 2053 | ||

| GJ 526 | HD 119850 | Boötes | 2013-07-10 | 2031 | Lone Signal |

| 55 Cnc | HD 75732 | Cancer | 2013-09-22 | 2053 | JAXA Space Camp (UDSC-1) |

| 55 Cnc | HD 75732 | Cancer | 2014-08-23 | 2054 | JAXA Space Camp (UDSC-2) |

| GJ273b | Luyten's Star | Canis Major | 2017-10-16 | 2030-11-03 | Sónar Calling GJ273b |

| Polaris | HIP 11767 | Ursa Minor | 2016-10-10 | 2450 | A Simple Response to an Elemental Message |

Potential risk

Active SETI has been heavily criticized due to the perceived risk of revealing the location of the Earth to alien civilizations, without some process of prior international consultation. Notable among its critics is scientist and science fiction author David Brin, particularly in his article "expose."[21]

However, Russian and Soviet radio engineer and astronomer Alexander L. Zaitsev has argued against these fears.[22][23] Indeed, Zaitsev argues that we should consider the risks of not reaching out to extraterrestrial civilizations.[24]

To lend a quantitative basis to discussions of the risks of transmitting deliberate messages from Earth, the SETI Permanent Study Group of the International Academy of Astronautics[25] adopted in 2007 a new analytical tool, the San Marino Scale.[26] Developed by Prof. Ivan Almar and Prof. H. Paul Shuch, the San Marino Scale evaluates the significance of transmissions from Earth as a function of signal intensity and information content. Its adoption suggests that not all such transmissions are created equal, thus each must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis before establishing blanket international policy regarding Active SETI.

In 2012, Jacob Haqq-Misra, Michael Busch, Sanjoy Som, and Seth Baum argued that while the benefits of radio communication on Earth likely outweigh the potential harms of detection by extraterrestrial watchers, the uncertainty regarding the outcome of contact with extraterrestrial beings creates difficulty in assessing whether or not to engage in long-term and large-scale METI.[27]

In 2015, João Pedro de Magalhães proposed transmitting an invitation message to any extraterrestrial intelligences watching us already in the context of the Zoo Hypothesis and inviting them to respond. By using existing television and radio channels, de Magalhães argued this would not put us in any danger, "at least not in any more danger than we are already if much more advanced extraterrestrial civilizations are aware of us and can reach the solar system."[28]

Douglas Vakoch, president of METI, argues that passive SETI itself is already an endorsement of active SETI, since "If we detect a signal from aliens through a SETI program, there’s no way to prevent a cacophony of responses from Earth."[29]

Beacon proposal

One proposal for a 10 billion watt interstellar SETI beacon was dismissed by Robert A. Freitas Jr. to be infeasible for a pre-Type I civilization on the Kardashev scale.[30] As a result, it has been suggested that civilizations must advance into Type I before mustering the energy required for reliable contact with other civilizations.

However, this 1980s technical argument assumes omni-directional beacons which may not be the best way to proceed on many technical grounds. Advances in consumer electronics have made possible transmitters that simultaneously transmit many narrow beams, covering the million or so nearest stars but not the spaces between.[31] This multibeam approach can reduce the power and cost to levels that are reasonable with current mid-2000s Earth technology.

Once civilizations have discovered each other's locations, the energy requirements for maintaining contact and exchanging information can be significantly reduced through the use of highly directional transmission technologies.

In 1974, the Arecibo Observatory transmitted a message toward the then-apparent position of the M13 globular cluster about 25,000 light-years away, for example, and the use of larger antennas or shorter wavelengths would allow transmissions of the same energy to be focused on even more remote targets, such as those attempted by Active SETI.

See also

References

- ↑ Zaitsev, A. (2006). "Messaging to Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence". arXiv:physics/0610031.

- ↑ Johnson, Steven (28 June 2017). "Greetings, E.T. (Please Don't Murder Us.)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ Vakoch, D. A. (2010). "Integrating Active and Passive SETI Programs: Prerequisites for Multigenerational Research" (PDF). Proceedings of the Astrobiology Science Conference 2010. p. 5213. Bibcode:2010LPICo1538.5213V. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-09.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (13 February 2015). "Should We Call the Cosmos Seeking ET? Or Is That Risky?". Phys.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ Ghosh, Pallab (12 February 2015). "Scientists in US are urged to seek contact with aliens". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Various (13 February 2015). "Regarding Messaging To Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) / Active Searches For Extraterrestrial Intelligence (Active SETI)". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ Shostak, Seth (28 March 2015). "Should We Keep a Low Profile in Space?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Busch, M. W.; Reddick, R. M. (2010). "Testing SETI Messages Design" (PDF). Proceedings of the Astrobiology Science Conference 2010. arXiv:0911.3976. Bibcode:2010LPICo1538.5070B. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-01.

- ↑ "Message Encoding – But, Can They Read It?". Lone Signal. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ "Recent Beams". Lone Signal. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑

Chapman, C. R. "Extending the syntax used by the Lone Signal Active SETI project". Lone Signal Active SETI. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013.

"Lone Signal & Jamesburg Earth Station Technologies - Technical Setup". Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-09. - ↑ Genevieve Valentine (March 2011). "You Never Get a Seventh Chance to Make a First Impression: An Awkward History of Our Space Transmissions". Lightspeed Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ Paul Gilster (18 November 2009). ""RuBisCo Stars" and the Riddle of Life". Centauri Dreams. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ "Humanity Responds to 'Alien' Wow Signal, 35 Years Later". SPACE.com. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ А. Л. Зайцев. "Передача и поиски разумных сигналов во Вселенной". Пленарный доклад на Всероссийской астрономической конференции ВАК-2004 "Горизонты Вселенной", Москва, МГУ, 7 июня 2004 года (in Russian). Институт радиотехники и электроники РАН. Archived from the original on 2012-02-16.

[A. L. Zaitsev. "Transmission and retrieval of intelligent signals in the universe". Keynote Address at the National Astronomical Conference VAK-2004 "Horizons of Universe", Moscow, MSU, 7 June 2004. Institute of Radio Engineering and Electronics RAS. ] - ↑ "interstellar radio message (IRM)". David Darliing. Archived from the original on 2008-01-11.

- ↑ "Is anybody listening out there?". BBC News. 9 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ↑ "MIR, LENIN, SSSR". Archived from the original on 2009-06-12.

Word MIR (it signifies both "peace" and "world" in Russian) was transmitted from the EPR on 19 November 1962, and words LENIN and SSSR (the Russian acronym for the Soviet Union) – on 24 November 1962, respectively were sent to the direction near the star HD131336 in the Libra constellation

- ↑ "Gliese 526". Lone Signal. Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "Alien e-mail reply to arrive in 2015?". ~Pink Tentacle. 14 May 2008. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ David Brin (September 2006) [last updated July 2008]. "Shouting at the Cosmos". Lifeboat Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ Zaitsev, Alexander L. (September 2008). "Sending and searching for interstellar messages". Acta Astronautica. 63 (5–6): 614–617. arXiv:0711.2368. Bibcode:2008AcAau..63..614Z. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2008.05.014 – via ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Alexander L. Zaitsev (2008). "Detection Probability of Terrestrial Radio Signals by a Hostile Super-civilization". Journal of Radio Electronics (5). Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ Alexander Zaitsev; Charles M. Chafer; Richard Braastad. "Making a Case for METI". SETI League. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ "Overview". International Academy of Astronautics – SETI Permanent Committee. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ "The San Marino Scale". International Academy of Astronautics – SETI Permanent Committee. Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ Haqq-Misra, J.; Busch, M. W.; Som, S. M.; Baum, S. D. (2013). "The benefits and harm of transmitting into space". Space Policy. 29: 40. doi:10.1016/j.spacepol.2012.11.006.

- ↑ de Magalhaes, J. P. (2015). "A direct communication proposal to test the Zoo Hypothesis". Space Policy. 38: 22–26. arXiv:1509.03652. doi:10.1016/j.spacepol.2016.06.001.

- ↑ Hannah Osborne (2017-11-16). "Scientists Have Sent Messages to Advanced Alien Civilizations—And Are Hoping for a Reply in 25 Years". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ↑ Freitas, R. A. (1980). "Interstellar Probes: A new approach to SETI". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 33: 95–100. Bibcode:1980JBIS...33...95F. Archived from the original on 2016-04-14.

- ↑ Scheffer, L. K. (2005). "A scheme for a high-power, low-cost transmitter for deep space applications". Radio Science. 40 (5): RS5012. Bibcode:2005RaSc...40.5012S. doi:10.1029/2005RS003243.

External links

- Interstellar Radio Messages

- ActiveSETI.org

- active-seti.info

- Making a Case for METI

- Self-Decoding Messages

- Should We Shout Into the Darkness?

- Error Correction Schemes In Active SETI

- The Evpatoria Messages

- Encounter 2001 Message

- METI: Messaging to Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence

- The Pros and Cons of METI from Centauri Dreams

- Classification of interstellar radio messages

- Lone Signal