Cosmos

The cosmos (UK: /ˈkɒzmɒs/, US: /-moʊs/) is the universe. Cosmos is used at times when the universe is regarded as a complex and orderly system or entity; the opposite of chaos.[1] The cosmos, and our understanding of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in cosmology, which is a very broad term covering any scientific, religious, or philosophical contemplation of the cosmos and its nature, or reasons for existing. Religious and philosophical approaches may include in their concept of the cosmos various spiritual entities or other matters deemed to exist outside our physical universe.

Etymology

The philosopher Pythagoras first used the term cosmos (Ancient Greek: κόσμος) for the order of the universe.[2][3] The term became part of modern language in the 19th century when geographer–polymath Alexander von Humboldt resurrected the use of the word from the ancient Greek, assigned it to his five-volume treatise, Kosmos, which influenced modern and somewhat holistic perception of the universe as one interacting entity.[4][5]

Cosmology

Cosmology is the study of the cosmos, and in its broadest sense covers a variety of very different approaches: scientific, religious and philosophical. All cosmologies have in common an attempt to understand the implicit order within the whole of being. In this way, most religions and philosophical systems have a cosmology.

When cosmology is used without a qualifier, it often signifies physical cosmology, unless the context makes clear that a different meaning is intended.

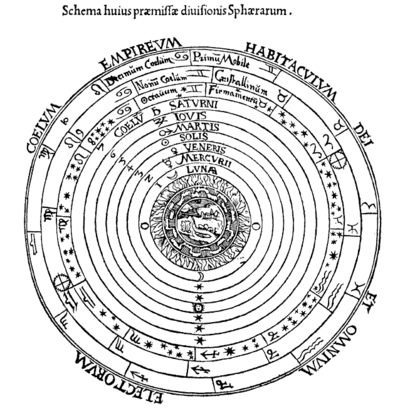

Physical cosmology

Physical cosmology (often simply described as 'cosmology') is the scientific study of the universe, from the beginning of its physical existence. It includes speculative concepts such as a multiverse, when these are being discussed. In physical cosmology, the term cosmos is often used in a technical way, referring to a particular spacetime continuum within a (postulated) multiverse. Our particular cosmos, the observable universe, is generally capitalized as the Cosmos.

In physical cosmology, the uncapitalized term cosmic signifies a subject with a relationship to the universe, such as 'cosmic time' (time since the Big Bang), 'cosmic rays' (high energy particles or radiation detected from space), and 'cosmic microwave background' (microwave radiation detectable from all directions in space).

According to Charles Peter Mason in Sir William Smith Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1870, see book screenshot for full quote), Pythagoreans described the universe.[6]

It appears, in fact, from this, as well as from the extant fragments, that the first book (from Philolaus) of the work contained a general account of the origin and arrangement of the universe. The second book appears to have been an exposition of the nature of numbers, which in the Pythagorean theory are the essence and source of all things. (p. 305)

Philosophical cosmology

Cosmology is a branch of metaphysics that deals with the nature of the universe, a theory or doctrine describing the natural order of the universe.[7] The basic definition of Cosmology is the science of the origin and development of the universe. In modern astronomy the Big Bang theory is the dominant postulation.

Religious cosmology

In theology, the cosmos is the created heavenly bodies (sun, moon, planets, and fixed stars). In Christian theology, the word is also used synonymously with aion[8] to refer to "worldly life" or "this world" or "this age" as opposed to the afterlife or world to come.

The 1870 book Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology noted[6]

- Thales dogma that water is the origin of things, that is, that it is that out of which every thing arises, and into which every thing resolves itself, Thales may have followed Orphic cosmogonies, while, unlike them, he sought to establish the truth of the assertion. Hence, Aristotle, immediately after he has called him the originator of philosophy brings forward the reasons which Thales was believed to have adduced in confirmation of that assertion; for that no written development of it, or indeed any book by Thales, was extant, is proved by the expressions which Aristotle uses when he brings forward the doctrines and proofs of the Milesian. (p. 1016)

- Plato, describes the idea of the good, or the Godhead, sometimes teleologically, as the ultimate purpose of all conditioned existence; sometimes cosmologically, as the ultimate operative cause; and has begun to develop the cosmological, as also the physico-theological proof for the being of God; but has referred both back to the idea of the Good, as the necessary presupposition to all other ideas, and our cognition of them. (p. 402)

The book The Works of Aristotle (1908, p. 80 Fragments) mentioned[9]

- Aristotle says the poet Orpheus never existed; the Pythagoreans ascribe this Orphic poem to a certain Cercon (see Cercops).

Bertrand Russell (1947) noted[10]

- The Orphics were an ascetic sect; wine, to them, was only a symbol, as, later, in the Christian sacrament. The intoxication that they sought was that of "enthusiasm," of union with the god. They believed themselves, in this way, to acquire mystic knowledge not obtainable by ordinary means. This mystical element entered into Greek philosophy with Pythagoras, who was a reformer of Orphism as Orpheus was a reformer of the religion of Dionysus. From Pythagoras Orphic elements entered into the philosophy of Plato, and from Plato into most later philosophy that was in any degree religious.

See also

References

- ↑ "cosmos". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Iamblichus, Pyth., β 59; Aetius ΙΙ 1.1.

- ↑ Anaxagoras further introduced the concept of a Cosmic Mind (Nous) ordering all things (Aetius Ι 3.5).

- ↑ Humboldt, Alexander von; Paul, Benjamin Horatio; von), Wilhelm Humboldt (Freiherr; Dallas, William Sweetland (1860). Cosmos: a sketch of a physical description of the universe. Harper & brothers.

- ↑ "Introducing Humboldt's Cosmos | Center for Humans & Nature". Center for Humans & Nature. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- 1 2 Sir William Smith (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. p. 305.

- ↑ "Definition of "Cosmology"". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ "Concerning Aion and Aionios". Saviour of All Fellowship. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Aristotle; Ross, W. D. (William David), 1877; Smith, J. A. (John Alexander), 1863-1939 (1908). The Works of Aristotle. p. 80.

- ↑ Bertrand Russell (1947). History of Western Philosophy.

External links

| Look up cosmos in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Cosmos – an Illustrated Dimensional Journey from microcosmos to macrocosmos – from Digital Nature Agency

- JPL Spitzer telescope photos of macrocosmos

- Macrocosm and Microcosm, in Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- Encyclopedia of Cosmos This is in Japanese.

- Cosmos – Illustrated Encyclopedia of Cosmos and Cosmic Law (in Russian)

- Greene, B. (1999). The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory. W.W. Norton, New York

- Hawking, S. W. (2001). The Universe in a Nutshell. Bantam Book.

- Yulsman, T. (2003). Origins: The Quest for our Cosmic Roots. Institute of Physics Publishing, London.