50000 Quaoar

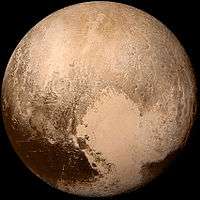

Quaoar imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2002 | |

| Discovery [1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by |

C. Trujillo M. E. Brown |

| Discovery site | Palomar Obs. |

| Discovery date | 6 June 2002 |

| Designations | |

| MPC designation | (50000) Quaoar |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkwɑːwɑːr/[lower-alpha 1] |

Named after |

Quaoar [2] (deity of the Tongva people) |

| 2002 LM60 | |

|

TNO [3] · cubewano [4][5] distant [1] | |

| Orbital characteristics [3] | |

| Epoch 23 March 2018 (JD 2458200.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 3 | |

| Observation arc | 62.24 yr (22,732 days) |

| Earliest precovery date | 25 May 1954 |

| Aphelion | 45.255 AU |

| Perihelion | 41.978 AU |

| 43.616 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0376 |

| 288.06 yr (105,214 d) | |

| 297.98° | |

| 0° 0m 12.24s / day | |

| Inclination | 7.9870° |

| 188.78° | |

| 147.67° | |

| Known satellites | 1 (Weywot; D: 81±11 km)[6] |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean diameter |

1110±5 km (occultation)[7] 1074±38 km[8] |

| Mass |

(1.4±0.1)×1021 kg[8][9] 0.12 Eris masses[10] |

Mean density |

1.99±0.46 g/cm3[7] 2.18+0.43 −0.36 g/cm3[8] |

| 17.6788 h[11] | |

| 0.109±0.007[7] | |

|

(moderately red) B–V =0.94±0.01[12] V−R = 0.64±0.01[12] | |

| 19.3[13] | |

|

2.82±0.06[7] 2.4[3] | |

|

| |

50000 Quaoar (/ˈkwɑːwɑːr/[lower-alpha 1]), provisional designation 2002 LM60, is a non-resonant trans-Neptunian object (cubewano) and possibly a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, located in the outermost region of the Solar System. It measures approximately 1110 kilometers in diameter or half the size of Pluto. The object was discovered by American astronomers Chad Trujillo and Michael Brown at the Palomar Observatory on 6 June 2002.[1]

Signs of water ice have been found, which suggests that cryovolcanism may be occurring. A small amount of methane is present on its surface, which can only be retained by the largest Kuiper belt objects.

In February 2007, Weywot, a 80-kilometer sized synchronous minor-planet moon in orbit of Quaoar was discovered by Michael Brown. Both objects were named after mythological figures from the Native American Tongva people in Southern California. Quaoar is the Tongva creator deity and Weywot is his son.[2]

Discovery

Quaoar was officially discovered on June 6, 2002, by astronomers Chad Trujillo and Michael Brown at the California Institute of Technology, from images acquired at the Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory.[1] The actual discovering image was taken on June 4, 2002, 05:41:40 UT and analyzed on June 5, 2002, 10:48:08 PDT.[14] The discovery of this magnitude 18.5 object, at the time located in the constellation Ophiuchus, was announced on October 7, 2002, at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. The earliest prediscovery image proved to be a May 25, 1954, plate from the Palomar observatory sky survey.[3] When Quaoar was just discovered, it was advertised as tenth planet by some press media.

Name

Quaoar is named for the Tongva creator god, following International Astronomical Union (IAU) naming conventions for non-resonant Kuiper belt objects. The Tongva are the native people of the area around Los Angeles, where the discovery of Quaoar was made. Brown et al. had picked the name with the more intuitive spelling Kwawar, but the preferred spelling among the Tongva was Qua-o-ar.

Prior to IAU approval of the name, Quaoar went by the provisional designation 2002 LM60. The minor planet number 50000 was not coincidence, but chosen to commemorate a particularly large object found in the search for a Pluto-sized object in the Kuiper belt, parallel to the similarly numbered 20000 Varuna. However, subsequent even-larger discoveries such as 136199 Eris were simply numbered according to the order in which their orbits were confirmed.

Size

In 2004, Quaoar was estimated to have a diameter of 1260±190 km,[15] subsequently revised downward, which at the time of discovery in 2002 made it the largest object found in the Solar System since the discovery of Pluto. Quaoar was later supplanted by Eris, Sedna, Haumea, and Makemake, though Sedna was later found to be somewhat smaller than Quaoar. Quaoar is about as massive as (if somewhat smaller than) Pluto's moon Charon, which is approximately 2 1⁄2 times as massive as Orcus. Quaoar is roughly one twelfth the diameter of Earth, one third the diameter of the Moon, and half the size of Pluto.

| Year | Diameter | Method | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1,260 km | imaging | [15] |

| 2007 | 844 km | thermal | [16] |

| 2010 | 890 km | thermal/imaging | [10] |

| 2013 | 1,074 km | thermal | [8] |

| 2013 | 1,110 km | occultation | [7] |

Quaoar was the first trans-Neptunian object to be measured directly from Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images, using a new, sophisticated method (see Brown’s pages for a non-technical description and his paper[15] for details). Given its distance Quaoar is on the limit of the HST resolution (40 milliarcseconds) and its image is consequently "smeared" on a few adjacent pixels. By comparing carefully this image with the images of stars in the background and using a sophisticated model of HST optics (point spread function (PSF)), Brown and Trujillo were able to find the best-fit disk size that would give a similar blurred image. This method was recently applied by the same authors to measure the size of Eris.

The uncorrected 2004 HST estimates only marginally agree with the 2007 infrared measurements by the Spitzer Space Telescope (SST) that suggest a higher albedo (0.19) and consequently a smaller diameter (844.4+206.7

−189.6 km).[16]

During the 2004 HST observations, little was known about the surface properties of Kuiper belt objects, but we now know that the surface of Quaoar is in many ways similar to those of the icy satellites of Uranus and Neptune. Adopting a Uranian-satellite limb darkening profile suggests that the 2004 HST size estimate for Quaoar was approximately 40% too large, and that a more proper estimate would be about 900 km. Using a weighted average of the SST and corrected HST estimates, Quaoar, as of 2010, can be estimated at about 890±70 km in diameter.[10]

On 4 May 2011 Quaoar occulted a 16th-magnitude star, which gave 1170 km as the longest chord and suggested an elongated shape.[17] New measurement from Herschel Space Observatory with revised data from SST suggested that Quaoar has a diameter of 1070±38 km and its satellite, Weywot, of 81±11 km.[8]

Classification

Because Quaoar is a binary object, the mass of the system can be calculated from the orbit of the secondary. Quaoar's estimated density of around 2.2 g/cm3 and estimated size of 1,100 km suggests that it is a dwarf planet. American astronomer Michael Brown estimates that rocky bodies around 900 km in diameter relax into hydrostatic equilibrium, and that icy bodies relax into hydrostatic equilibrium somewhere between 200 and 400 km.[18] With an estimated mass greater than 1.6×1021 kg, Quaoar has the mass and diameter "usually" required for being in hydrostatic equilibrium according to the 2006 IAU draft definition of a planet (5×1020 kg, 800 km),[19] and Brown states that Quaoar "must be" a dwarf planet.[20] Light-curve-amplitude analysis shows only small deviations, suggesting that Quaoar is indeed a spheroid with small albedo spots and hence a dwarf planet.[21]

Hit-and-run collision

Planetary scientist Erik Asphaug has suggested that Quaoar may have collided with a much larger body, stripping the lower-density mantle from Quaoar, and leaving behind the denser core. He envisions that Quaoar was originally covered by a mantle of ice that made it 300 to 500 kilometers bigger than it is today, and that it collided with another Kuiper-belt body about twice its size—an object roughly the diameter of Pluto (or even approaching the size of Mars),[22] possibly Pluto itself.[23] This model was made assuming Quaoar actually had a density of 4.2 g/cm3, but more-recent estimates have given it a more Pluto-like density of only 2 g/cm3, with no more need for the collision theory.

Orbit

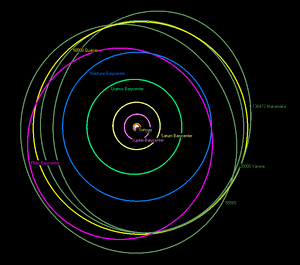

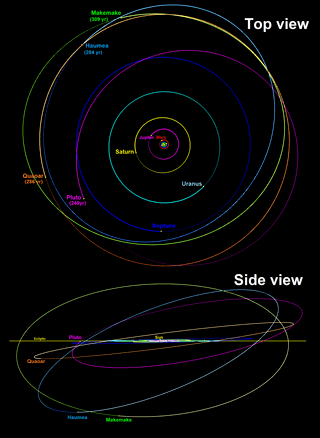

Quaoar orbits at about 43.3 astronomical units (6.48×109 km; 4.02×109 mi) from the Sun with an orbital period of 284.5 years. Its orbit is nearly circular and moderately inclined at approximately 8°, typical for the population of small classical Kuiper-belt objects (KBO) but exceptional among the large KBOs. Pluto, Makemake, Haumea, Orcus, Varuna, and Salacia are all on highly inclined, more eccentric orbits.

Quaoar is the largest body that is classified as a cubewano by both the Minor Planet Center[5] and the Deep Ecliptic Survey.[4][24]

The polar view compares the near-circular orbit of Quaoar to the highly eccentric (e=0.25) orbit of Pluto (Quaoar’s orbit in blue, Pluto’s in red, Neptune in grey). The circles illustrate the positions in April 2006, relative sizes, and colours. The perihelia (q), aphelia (Q) and the dates of passage are also marked.

At 43 AU and a near-circular orbit, Quaoar is not significantly perturbed by Neptune,[4] unlike Pluto, which is in 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune. The ecliptic view illustrates the relative inclinations of the orbits of Quaoar and Pluto. Note that Pluto's aphelion is beyond (and below) Quaoar's orbit, so that Pluto is closer to the Sun than Quaoar at some times of its orbit, and farther at others.

As of 2008, Quaoar was only 14 AU[25] from Pluto, which made it the closest large body to the Pluto–Charon system. By Kuiper belt standards this is very close.

Physical characteristics

Quaoar's albedo could be as low as 0.1, which would still be much higher than the lower estimate of 0.04 for Varuna. This may indicate that fresh ice has disappeared from Quaoar's surface. The surface is moderately red, meaning that Quaoar is relatively more reflective in the red and near-infrared than in the blue. 20000 Varuna and 28978 Ixion are also moderately red in the spectral class. Larger KBOs are often much brighter because they are covered in more fresh ice and have a higher albedo, and thus they present a neutral colour (see colour comparison).

A 2006 model of internal heating via radioactive decay suggested that, unlike Orcus, Quaoar may not be capable of sustaining an internal ocean of liquid water at the mantle–core boundary.[26]

Cryovolcanism

In 2004, scientists were surprised to find signs of crystalline ice on Quaoar, indicating that the temperature rose to at least −160 °C (110 K or −260 °F) sometime in the last ten million years.[27]

Speculation began as to what could have caused Quaoar to heat up from its natural temperature of −220 °C (55 K or −360 °F). Some have theorized that a barrage of mini-meteors may have raised the temperature, but the most discussed theory speculates that cryovolcanism may be occurring, spurred by the decay of radioactive elements within Quaoar's core.[28] Since then (2006), crystalline water ice was also found on Haumea, but present in larger quantities and thought to be responsible for the very high albedo of that object (0.7).[29]

More precise (2007) observations of Quaoar's near infrared spectrum indicate the presence of small (5%) quantity of (solid) methane and ethane. Given its boiling point (112 K), methane is a volatile ice at average Quaoar surface temperatures, unlike water ice or ethane (boiling point 185 K). Both models and observations suggest that only a few larger bodies (Pluto, Eris, Makemake) can retain the volatile ices whereas the dominant population of small TNOs lost them. Quaoar, with only small amounts of methane, appears to be in an intermediary category.[30]

In 2019, when the New Horizons mission visits the small Kuiper-belt object (486958) 2014 MU69 after having visited Pluto in 2015, knowledge of the surfaces of KBOs should improve.

Satellite Weywot

A moderately red Quaoar and its moon Weywot (artist's conception) | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Michael E. Brown |

| Discovery date | February 22, 2007 |

| Designations | |

| MPC designation | (50000) Quaoar |

| Pronunciation | /ˈweɪwɒt/ |

| S/2006 (50000) 1 | |

| Orbital characteristics prograde orbit[10] | |

| Periapsis | 12,470±688 km |

| Apoapsis | 16,530±912 km |

| 14,500±800 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.14±0.04 |

| 12.438±0.005 d | |

| Inclination | 14±4° |

| Satellite of | Quaoar |

| Physical characteristics | |

Equatorial radius |

40.5±5.5 km[8] 37 km[10] |

| 24.9±0.2[8] | |

| 8.3[lower-alpha 2] | |

Quaoar has one known moon, Weywot (full designation (50000) Quaoar I Weywot). Its discovery by Michael E. Brown was reported in IAUC 8812 on 22 February 2007, based on imagery taken on 14 February 2006.[6][31] The satellite was found at 0.35 arcsec from Quaoar with an apparent magnitude difference of 5.6.[32]

Two possible orbits have been determined from the observations: the first is a prograde orbit with an inclination of 14°, the second a retrograde orbit with an inclination of 30° (150°); the other parameters are very similar between the two orbits. It orbits at a distance of 14,500 km from the primary and has an eccentricity of about 0.14, it completes one orbit in about 12.5 days.[10]

From the surface of Quaoar and at a point where Weywot is at zenith it would have an angular diameter of 15.9 arcminutes at apoapsis and 21.4 arcminutes at periapsis, in comparison the Moon's size varies between 29.4 and 33.5 arcminutes.[lower-alpha 3] Its apparent magnitude at full phase would be about -3, comparable to Jupiter at maximum brightness.[lower-alpha 2]

Assuming an equal albedo and density to the primary, the apparent magnitude suggests that the moon has a diameter of about 74 km (1⁄12 of Quaoar). Weywot is estimated to only have 1⁄2000 the mass of Quaoar.[10]

Name

Upon discovery, Weywot was issued a provisional designation, S/2006 (50000) 1. Brown left the choice of a name up to the Tongva (whose creator god Quaoar had been named after), who chose the sky god Weywot, son of Quaoar.[33] The name was made official in MPC #67220 published on October 4, 2009.[34]

Exploration

It was calculated that a flyby mission to Quaoar could take 13.57 years using a Jupiter gravity assist, based on launch dates of 25 December 2016, 22 November 2027, 22 December 2028, 22 January 2030 or 20 December 2040. Quaoar would be 41 to 43 AU from the Sun when the spacecraft arrives.[35] In July 2016 New Horizons spacecraft took a sequence of four images of Quaoar from a distance of about 14 AU.[36]

Pontus Brandt at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and his colleagues have studied an interstellar probe that would fly by Quaoar in the 2030s before continuing to the interstellar medium.[37][38] Quaoar is a logical flyby target for such a mission due to its close proximity to the heliospheric nose.

Notes

- 1 2 Brown's website[39] gives a three-syllable pronunciation, /ˈkwɑːoʊwɑːr/, as an approximation of the Tongva pronunciation [ˈkʷaʔuwar]. However, his students pronounce it with two syllables, /ˈkwɑːwɑːr/, reflecting the usual English spelling and pronunciation of the deity, Kwawar.[40]

- 1 2 Using the apparent magnitude from Earth and the formula listed in the Absolute Magnitude article to find out its absolute magnitude (we also could have added the difference in apparent magnitude to Quaoar's absolute magnitude listed above to get the same result), then using the same formula again to find its apparent magnitude from the surface of Quaoar. Semi-major axis distance used in both cases.

- ↑ Using values for moon size, distance and planet radius listed above and solving for the angle of separation between the center of the moon and its edge as seen from the surface.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "50000 Quaoar (2002 LM60)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (50000) Quaoar. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 895. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 50000 Quaoar (2002 LM60)" (2016-08-19 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 Buie, Marc W. (2006-05-17). "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 50000". SwRI (Space Science Department). Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- 1 2 "MPEC 2008-O05 : Distant Minor Planets (2008 Aug. 2.0 TT)". IAU Minor Planet Center. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 17 July 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- 1 2 Daniel W. E. Green (2007-02-22). "IAUC 8812: Sats of 2003 AZ84, (50000), (55637), (90482)". International Astronomical Union Circular. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Braga-Ribas, F.; Sicardy, B.; Ortiz, J. L.; Lellouch, E.; Tancredi, G.; Lecacheux, J.; et al. (August 2013). "The Size, Shape, Albedo, Density, and Atmospheric Limit of Transneptunian Object (50000) Quaoar from Multi-chord Stellar Occultations". The Astrophysical Journal. 773 (1): 13. Bibcode:2013ApJ...773...26B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/773/1/26. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fornasier, S.; Lellouch, E.; Müller, T.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Panuzzo, P.; Kiss, C.; et al. (July 2013). "TNOs are Cool: A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. VIII. Combined Herschel PACS and SPIRE observations of nine bright targets at 70-500 µm". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 555: 22. arXiv:1305.0449v2. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A..15F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321329. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Fraser, Wesley C.; Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E.; Bouchez, Antonin (January 2013). "The mass, orbit, and tidal evolution of the Quaoar-Weywot system" (PDF). Icarus. 222 (1): 357–363. arXiv:1211.1016. Bibcode:2013Icar..222..357F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.11.004. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fraser, Wesley C.; Brown, Michael E. (May 2010). "Quaoar: A Rock in the Kuiper Belt" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 714 (2): 1547–1550. arXiv:1003.5911. Bibcode:2010ApJ...714.1547F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/714/2/1547. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ "LCDB Data for (50000) Quaoar". Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB). Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 Tegler, Stephen C. (1 February 2007). "Kuiper Belt Object Magnitudes and Surface Colors". Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ "AstDys (50000) Quaoar Ephemerides". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Chad Trujillo. "Frequently Asked Questions About Quaoar". Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Michael E.; Trujillo, Chadwick A. (April 2004). "Direct Measurement of the Size of the Large Kuiper Belt Object (50000) Quaoar" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 127 (4): 2413–2417. Bibcode:2004AJ....127.2413B. doi:10.1086/382513. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- 1 2 Stansberry, J.; Grundy, W.; Brown, M.; Cruikshank, D.; Spencer, J.; Trilling, D.; et al. (December 2007). "Physical Properties of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects: Constraints from the Spitzer Space Telescope" (PDF). The Solar System Beyond Neptune: 161–179. Bibcode:2008ssbn.book..161S. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Braga-Ribas et al. 2011, "Stellar Occultations by TNOs: the January 08, 2011 by (208996) 2003 AZ84 and the May 04, 2011 by (50000) Quaoar", EPSC Abstracts, vol. 6

- ↑ Brown, Michael E. "The-Dwarf-Planets". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ "The IAU draft definition of "planet" and "plutons"". IAU. August 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Michael E. "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system?". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Tancredi, Gonzalo; Favre, Sofía (June 2008). "Which are the dwarfs in the Solar System?" (PDF). Icarus. 195 (2): 851–862. Bibcode:2008Icar..195..851T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.12.020. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ George Musser (2009-10-13). "What do we really know about the Kuiper Belt? Fifth dispatch from the annual planets meeting". Scientific American blog. Archived from the original on 14 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ↑ Ron Cowen (2009-01-04). "On the Fringe". ScienceNews. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ↑ A lot of TNOs classified as cubewanos by the MPC are classified as ScatNear (Scattered by Neptune) by the DES.

- ↑ "50000 Quaoar distance (AU) from Pluto". Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Hussmann, Hauke; Sohl, Frank; Spohn, Tilman (November 2006). "Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects" (PDF). Icarus. 185 (1): 258–273. Bibcode:2006Icar..185..258H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005.

- ↑ Jewitt, D.C.; J. Luu (2004). "Crystalline water ice on the Kuiper belt object (50000) Quaoar". Nature. 432 (7018): 731–3. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..731J. doi:10.1038/nature03111. PMID 15592406. . Reprint on Jewitt's site (pdf)

- ↑ Crystalline Ice on Kuiper Belt Object (50000) Quaoar – article about crystalline ice on Quaoar

- ↑ Trujillo; Brown; Barkume; Schaller; Rabinowitz (2007). "The Surface of 2003EL61 in the Near Infrared". The Astrophysical Journal. 655 (2): 1172. arXiv:astro-ph/0601618. Bibcode:2007ApJ...655.1172T. doi:10.1086/509861.

- ↑ Schaller, E. L.; Brown, M. E. (November 2007). "Detection of Methane on Kuiper Belt Object (50000) Quaoar" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 670 (1): L49–L51. arXiv:0710.3591. Bibcode:2007ApJ...670L..49S. doi:10.1086/524140. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Wm. Robert Johnston (2008-11-25). "(50000) Quaoar". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Distant EKO The Kuiper Belt Electronic newsletter, March 2007

- ↑ "Heavenly Bodies and the People of the Earth", Nick Street, Search Magazine, July/August 2008

- ↑ MPC 67220

- ↑ McGranaghan, R.; Sagan, B.; Dove, G.; Tullos, A.; Lyne, J. E.; Emery, J. P. (2011). "A Survey of Mission Opportunities to Trans-Neptunian Objects". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 64: 296–303. Bibcode:2011JBIS...64..296M.

- ↑ "New Horizons Spies a Kuiper Belt Companion". The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. August 31, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Triennial Earth Sun-Summit". Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ TVIW (2017-11-04), 22. Humanity's First Explicit Step in Reaching Another Star: The Interstellar Probe Mission, retrieved 2018-07-24

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions About Quaoar

- ↑ E. L. Schaller, M. E. Brown, "Detection of Additional Members of the Haumea Collisional Family via Infrared Spectroscopy". AAS DPS conference, 13 Oct. 2008; also podcast: Dwarf Planet Haumea (Darin Ragozzine) at 3′18″

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quaoar. |

- Quaoar discoverers' webpage

- Quaoar could have hit a bigger Pluto-sized body at high speeds (Video Credit: Craig Agnor, E. Asphaug)

- Data at Johnston's Archive

- Chilly Quaoar had a warmer past – Nature.com article

- Cryovolcanism on Charon and other Kuiper Belt Objects

- AstorbDB, Lowell Observatory

- 50000 Quaoar at the JPL Small-Body Database

_(cropped).jpg)