1st Rhode Island Regiment

For the Civil War and Spanish–American War units see 1st Rhode Island Infantry.

| Varnum's Regiment 9th Continental Infantry Regiment 1st Rhode Island Regiment Rhode Island Regiment Rhode Island Battalion | |

|---|---|

A 1781 watercolor of a black infantryman of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Army at the Yorktown Campaign. The 1st Rhode Island was one of the few regiments in the Continental Army which had a large number of black soldiers in its ranks. | |

| Active | 1775–1783 |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Part of | Rhode Island Line |

| Nickname(s) |

Varnum's Continentals (1775–76) Black Regiment (1778–80) |

| Colors | white uniforms |

| Engagements |

Siege of Boston New York campaign Battle of Red Bank Battle of Rhode Island Siege of Yorktown |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

James Mitchell Varnum, Christopher Greene, Jeremiah Olney |

| Insignia | |

| War Flag |

|

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment (also known as Varnum's Regiment, the 9th Continental Regiment, the Black Regiment, and Olney's Battalion) was a regiment in the Continental Army from Rhode Island during the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). It was one of the few units in the Continental Army to serve through the entire war.

The unit went through several incarnations and name changes, like most regiments of the Continental Army. It became well known as the "Black Regiment" because it had several companies of black soldiers. It is regarded as the first black military regiment, despite the fact that its ranks were not exclusively black.[1]

Regimental history

Varnum's Regiment (1775)

The 1st Rhode Island was initially formed by the Colonial government before being taken into the Continental army. The revolutionary Rhode Island Assembly authorized the regiment on 6 May 1775 as part of the Rhode Island Army of Observation. The regiment was organized on 8 May 1775 under Colonel James Mitchell Varnum, and was therefore often known as "Varnum's Regiment." It originally consisted of eight companies of volunteers from Kent and King Counties.

Varnum marched the regiment to Roxbury, Massachusetts in June 1775, where it took part in the siege of Boston as part of the Army of Observation. It was adopted into the Continental Army by act of Congress on 14 June 1775. It was expanded to ten companies on 28 June, and was assigned to General Nathanael Greene's Brigade in General George Washington's Main Army on 28 July. General Washington officially took command of the Continental Army upon his arrival in Cambridge, Massachusetts on 3 July 1775.

The soldiers of Varnum's Regiment had enlisted until the end of 1775, like all others in the Continental Army, and the Regiment was discharged on December 31, along with the remainder of the Army.

9th Continental Regiment (1776)

The Continental Army was completely reorganized at the beginning of 1776, with many regiments receiving new names and others being disbanded. Enlistments were for one year. Varnum's Regiment was reorganized with eight companies on 1 January 1776 and re-designated as the 9th Continental Regiment. Under Colonel Varnum, the regiment remained near Boston until the British evacuated the city in March. It was then ordered to Long Island and took part in the disastrous New York and New Jersey campaign, including the Battle of Long Island and the Battle of Harlem Heights, retreating from New York with the Main Army. The Continental Army was reorganized at the end of the year, as was the case in 1775, but soldiers were now given the option of enlisting for "three years or the war", unlike the previous practice of enlisting only until the end of the year.

1st Rhode Island Regiment (1777–80)

The Continental Army was reorganized once again in 1777, and the 9th Continental Regiment was re-designated as the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Colonel Varnum was promoted to brigadier general and was succeeded by Colonel Christopher Greene, a distant cousin of General Nathanael Greene. Under Colonel Greene, the regiment successfully defended Fort Mercer at the Battle of Red Bank on 22 October 1777 against an assault by 2,000 Hessians.

%2C_by_Jean-Baptiste-Antoine_DeVerger.png)

The "Black Regiment" (1778–81)

Blacks had been barred from military service in the Continental Army from November 12, 1775 until February 23, 1778. Rhode Island was having difficulties recruiting enough white men to meet the troop quotas set by the Continental Congress in 1778, so the Rhode Island Assembly decided to pursue a suggestion made by General Varnum to enlist slaves in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Varnum had raised the idea in a letter to George Washington, who forwarded it to the governor of Rhode Island without explicitly approving or disapproving of the plan.[2] On 14 February 1778, the Rhode Island General Assembly voted to allow the enlistment of "every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave" who chose to do so, and voted that "every slave so enlisting shall, upon his passing muster before Colonel Christopher Greene, be immediately discharged from the service of his master or mistress, and be absolutely free."[3] The owners of slaves who enlisted were to be compensated by the Assembly in an amount equal to their market value.

A total of 88 slaves enlisted in the regiment over the next four months, as well as some free black men. The regiment eventually totaled about 225 men; probably fewer than 140 of these were black.[4] The 1st Rhode Island became the only regiment of the Continental Army to have segregated companies of black soldiers; other regiments that allowed black men to enlist were integrated. The enlistment of slaves had been controversial, and no more non-white men were enlisted after June 1778. The unit continued to be known as the "Black Regiment" even though only white men were recruited to replace losses, a process which eventually made it an integrated unit.[5]

Under Colonel Greene, the regiment fought in the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. It played a fairly minor—but praised—role in the battle, where it successfully repelled three charges by the Hessians. The regiment suffered three killed, nine wounded, and eleven missing.[6]

Battle of Rhode Island

The first engagement of the Black Regiment came in 1778 at the Battle of Rhode Island, when the Continental forces were forced to withdraw, rather than being completely routed.[6] The regiment held the line under the leadership of Colonel Greene, even though the British expected to break through where the Rhode Island Regiment was.[6]

The regiment was situated behind a thicket in the valley which gave them a strong defensive position.[7] Repeated attacks from British regulars and Hessian forces failed to break the line and allowed the successful retreat of Sullivan’s army.[6] Historian Sidney Rider notes that the Hessians charged three times and were repulsed each time.[7] According to Rider, the Hessian Colonel “applied to exchange his command and go to New York, because he dared not lead his regiment” into battle again, “lest his men should shoot him for having caused them so much loss.”[7] The retreat lasted a total of four hours, with six Continental brigades retreating.[8]

Gretchen Adams concludes that the retreat of Sullivan’s army was successful because the Continental Army was able to sustain low casualties and preserve their equipment, despite the aggressive charges made by British regulars and Hessian forces.[6] Sullivan praised the Rhode Island Regiment for its actions, saying that they bore “a proper share of the day's honors.”[6] General Lafayette proclaimed the battle as “the best fought action of the war.”[8]

The regiment saw little action over the next few years since the focus of the war shifted to the south.

Rhode Island Regiment (1781–1783)

On 1 January 1781, the regiment was consolidated with the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment and Sherburne's Additional Continental Regiment and was re-designated as the Rhode Island Regiment. The regiment spent the early months of 1781 in an area of the Hudson River Valley called by some historians the "Neutral Zone".

Campaign in the Neutral Zone

The "Neutral Zone" was an area in the Hudson River Valley described as “a desolate, sparsely populated buffer zone between the forces of the English to the South and the Americans to the North.”[9] People who continued to live in the area had to deal with “theft, murder, and destruction” by renegade groups, such as the “cowboys” or the “skinners.”[10] These renegade groups “cloaked their plundering under an alleged allegiance to one of the combatants.”[10] To whichever side the renegade groups leaned, they would forage for goods to sustain “both men and beasts of burden.”[10]

The constant foraging and raiding in the neutral zone, especially by the British supporting “cowboys,” caused Major-General Heath to command Colonel Greene and the Black Regiment to defend Pines Bridge on the Croton River from “marauding Cowboys” who frequently made incursions from their base in Morrisiania (South Bronx), under the command of insurgent leader James Delancy.[10] However, on the 14th May 1781, Colonel Delancey and his Cowboys assaulted Pines Bridge and caught Colonel Greene and the Black Regiment by surprise.[10] The Cowboys scored a resounding victory, killing “Colonel Greene, another officer, and many of the black troops.”[10] The black troops were reported to have “defended their beloved Col. Greene so well that it was only over their dead bodies that the enemy reached and murdered him.”[10]

Last years

In May 1781, Colonel Greene, Major Ebenezer Flagg and several black soldiers were killed in a skirmish with Loyalists at Greene's headquarters on the Croton River in what is today the town of Yorktown in Westchester County, New York. (Major Flagg was the great great grandfather of Alice Claypoole Gwynn who married Cornelius Vanderbilt II and is an ancestor of CNN reporter Anderson Cooper.)

With Colonel Greene's death, command of the regiment devolved on Lieutenant Colonel Jeremiah Olney. Under Olney's command, the regiment took part in the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781, which proved to be the last major battle of the Revolution.

After Yorktown, the regiment moved with the Main Army to Newburgh, New York where its primary purpose was to be ready to react in the event British forces in city of New York went on the offensive.

Rhode Island Battalion (1783)

On 1 March 1783 the regiment was reorganized into six companies and re-designated as the Rhode Island Battalion (a.k.a. "Olney's Battalion"). On 15 June 1783, the veteran "during the war" enlisted men of the Rhode Island Regiment were discharged at Saratoga, New York. The remaining soldiers of the Battalion who were enlisted for "three years" were organised into a small battalion of two companies. After the British evacuated New York on 25 November, the Rhode Island Battalion was disbanded on 25 December 1783 at Saratoga, New York. It was one of the few units in the Continental Army to have served through the entirety of the Continental Army's existence.

Disbandment

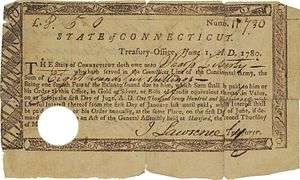

The Rhode Island Regiment served its final days in Saratoga, New York, under the command of Major William Allen.[12] The regiment was left waiting in Saratoga for months, with low supplies and a terrible snowstorm until December 25, 1783, when Major William Allen and Adjutant Jeremiah Greenman printed the discharge certificates.[13] The discharged troops were “dumped back into civilian society,” with only the white soldiers being guaranteed 100 acres of bounty land from the Federal Government, as well as a pension.[12]

The Rhode Island General Assembly had already guaranteed the African-Americans who had served in the war their freedom after the war.[6] However, the Rhode Island General Assembly, on February 23, 1784 passed an act that forbade “any person born in Rhode Island after March 1, 1784 from being made a slave."[14] The act also stipulated that children born into existing slaves were to be supported financially by the Rhode Island town they were born in.[12] During the same meeting Col. Olney presented the two colors of Rhode Island’s Continental Regiment to the General Assembly, and they have been housed in the State House ever since.[12] Colonel Olney had promised his men his “interest in their favour,” and he continued to advocate for his former troops right to remain free, and to have the government pay them the wages or pensions that they deserved.[6]

In June 1784, thirteen African-American veterans of the Rhode Island Regiment hired Samuel Emory to present their claims for back pay to the War Department Accounts Office, in order to help alleviate the financial difficulties that most African-American veterans faced after the war.[12] In response the Rhode Island Assembly passed a special act for these soldiers on February 28, 1785. The act called for “the support of paupers, who heretofore were slaves, and enlisted into the Continental battalions.”[14] Therefore, any “Indian, negro or mulatto” who was sick or unable to support himself must be taken care of by the town council of where they live.[14] While most colored veterans remained in Rhode Island, many moved onto the 100 acres of Bounty Land they were promised in either New York or Ohio. Most veterans, including white ones, who survived into their 50s or 60s were generally in desperate poverty because of the economic depression that occurred after the end of the Revolution.

Significant campaigns and battles

- Siege of Boston (May 1775 to March 17, 1776)

- Battle of Bunker Hill (June 1775)

- Battle of Long Island (August 22, 1776)

- Battle of Harlem Heights (September 16, 1776)

- Battle of White Plains (October 28, 1776)

- Battle of Trenton (January 2, 1777)

- Battle of Princeton (January 3, 1777)

- Battle of Red Bank (October 22, 1777)

- Siege of Fort Mifflin (November 1777)

- Valley Forge (December 1777 to March 1778)

- Battle of Rhode Island (August 29, 1778)

- Stationed at Bristol, Rhode Island (September 1778)

- Winter Quarters in Warren, Rhode Island (December 1778)

- Aquidneck Island (October 1779 to January 1781)

- Battle of Pine's Bridge (May 14, 1781)

- Siege and Battle of Yorktown (September 28 to October 19, 1781)

- Quartered in upstate New York (November 1781 to December 25, 1783)

Senior officers

Colonels and commanding officers

- Colonel James M. Varnum; 3 May 1775 - 27 February 1777 (promoted to brigadier general)

- Colonel Christopher Greene; 27 February 1777 - 14 May 1781 (killed in action)

- Lieutenant Colonel Commandant Jeremiah Olney; 14 May 1781 - 25 December 1783 (discharged)

Lieutenant Colonels

- James Babcock; 3 May 1775 - 31 December 1775 (discharged)

- Archibald Crary; 1 January 1776 - 31 December 1776 (discharged)

- Adam Comstock; 1 January 1777 - April 1778 (resigned)

- Samuel Ward Jr.; 5 May 1779 (date of rank 26 May 1778) - 31 December 1780 (retired)

- Jeremiah Olney; 1 January 1781 - 14 May 1781 (became regimental commander)

Majors

- Christopher Greene; 3 May 1775 - 31 December 1775 (taken prisoner)

- Christopher Smith; 1 January 1776 - 27 October 1776 (transferred to 2nd Rhode Island Regiment)

- Henry Sherburne; 28 October 1776 - 11 January 1777 (promoted to colonel)

- Samuel Ward Jr.; 12 January 1777 - 26 May 1778 (promoted to lieutenant colonel)

- Silas Talbot; 10 October 1777 (date of rank 1 September 1777) - 12 November 1778 (promoted to lieutenant colonel)

- Ebenezer Flagg; 5 May 1779 (date of rank 26 May 1778) - 14 May 1781 (killed in action)

- Coggeshall Olney; 25 August 1781 (date of rank 14 May 1781) - 17 March 1783 (resigned)

- John S. Dexter; 25 August 1781 (date of rank 14 May 1781) - 3 November 1783 (discharged)

Legacy

There is a monument to the 1st Rhode Island Regiment at Patriots Park in Portsmouth, Rhode Island on the site of the Battle of Rhode Island.

The flag of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment is preserved at the Rhode Island State House in Providence.

The Varnum Continentals is a historic military command founded in 1907 and located in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. Their ceremonial unit portrays the 1st Rhode Island Regiment during the early months of the American Revolution while it was under the command of Colonel James Varnum.

The home of General Varnum, called the Varnum House, in East Greenwich, Rhode Island is owned by the Varnum Continentals and is open to the public on weekends from April to October. There is a portrait of General Varnum in the Varnum house.

There is a portrait of Colonel Christopher Greene in the Hay Library at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Colonel Greene and Major Flagg are buried at the First Presbyterian Church in Yorktown, New York where there is a large monument in their honor, about two miles north of the site of their deaths. There is also a plaque next to the monument in honor of the African-American soldiers who died defending them.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "THE FIRST RHODE ISLAND". Archived from the original on 3 July 2007.

- ↑ Lengel, General George Washington, p. 314.

- ↑ Lanning, African Americans in the Revolutionary War, p. 205.

- ↑ Lanning, African Americans in the Revolutionary War, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Lanning, African Americans in the Revolutionary War, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Adams, Gretchen. "Deeds of Desperate Valor: The First Rhode Island Regiment". UNH.

- 1 2 3 Rider, Sidney (1880). "Rhode Island Historical Tracts". Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. 10: 59.

- 1 2 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem; Steinberg, Alan (2000). Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African American Achievement. New York, NY: Perennial. p. 31.

- ↑ Williams-Myers, A.J (2007). "Out of the Shadows: African Descendants -- Revolutionary Combatants in The Hudson River Valley; A Preliminary Historical Sketch". Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. 31 (1): 96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Williams-Myers, A.J (2007). "Out of the Shadows: African Descendants -- Revolutionary Combatants in The Hudson River Valley; A Preliminary Historical Sketch". Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. 31 (1): 97.

- ↑ "Unknown Pay warrant to African American soldier". Gilder Lehrman Lounge.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Popek, Daniel (2015). They “... Fought Bravely, but Were Unfortunate:”: The True Story of Rhode Island’s “Black Regiment” and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island’s Continental Line, 1777-1783. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 1784.

- ↑ Popek, Daniel (2015). They “... Fought Bravely, but Were Unfortunate:”: The True Story of Rhode Island’s “Black Regiment” and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island’s Continental Line, 1777-1783. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 1783.

- 1 2 3 Popek, Daniel (2015). They “... Fought Bravely, but Were Unfortunate:”: The True Story of Rhode Island’s “Black Regiment” and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island’s Continental Line, 1777-1783. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 1785.

References

- Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem; Steinberg, Alan (2000). Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African American Achievement. New York, NY: Perennial. 380813416

- Adams, Gretchen A. "Deeds of Desperate Valor: The First Rhode Island Regiment". University of New Hampshire (n.d.).

- Lanning, Michael Lee. African Americans in the Revolutionary War. New York: Citadel Press, 2005.

- Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. New York: Random House, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-6081-8.

- Popek, Daniel M. (2015). They “... Fought Bravely, but Were Unfortunate:”: The True Story of Rhode Island’s “Black Regiment” and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island’s Continental Line, 1777-1783. AuthorHouse.

- "Rhode Island Units in the Revolutionary War." Rhodeislandsar.org. N.p., n.d. Web.

- Rider, Sidney S. (1880). "Rhode Island Historical Tracts". Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. 10: 1–226.

- Wright, Robert K. The Continental Army. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1983. Available, in part, online from the U.S. Army website.

- Williams-Myers, A.J. (2007). "Out of the Shadows: African Descendants -- Revolutionary Combatants in The Hudson River Valley; A Preliminary Historical Sketch". Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. ProQuest. 31 (1): 91–111.

Further reading

- "Death Seem'd to Stare": The New Hampshire And Rhode Island Regiments at Valley Forge by Joseph Lee Boyle, Clearfield Co, 1995 ISBN 0-8063-5267-1

- Greene, Lorenzo J. "Some Observations on the Black Regiment of Rhode Island in the American Revolution." The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 37, No. 2, April 1952

- Popek, Daniel M. They '...fought bravely, but were unfortunate:' The True Story of Rhode Island's 'Black Regiment' and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island's Continental Line, 1777-1783, AuthorHouse, November 2015.

- Geake, Robert. 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Westholme Publishing, 2016. ISBN 1594162689

- Rees, John U. "They were good soldiers.": African Americans in the Continental Army, and General Glover's Soldier-Servants." Military Collector & Historian 62, no. 2 (Summer2010 2010): 139-142. America: History & Life, EBSCOhost.