1975 in the Vietnam War

| 1975 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A VNAF UH-1H Huey loaded with Vietnamese evacuees on the deck of the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Midway during Operation Frequent Wind, 29 April 1975. | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

| US: | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| US: 161 killed[1] | |||

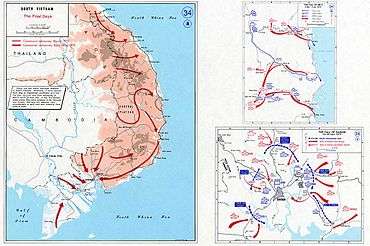

1975 marked the end of the Vietnam War, sometimes called the Second Indochina War or the American War. The North Vietnamese army (PAVN) launched the Spring Offensive in March, the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) was quickly defeated. The communist North Vietnamese captured Saigon on April 30, accepting the surrender of South Vietnam. In the final days of the war, the United States, which had supported South Vietnam for many years, carried out an emergency evacuation of its civilian and military personnel and more than 130,000 Vietnamese.

At the beginning of the Spring Offensive the balance of forces in Vietnam was approximately as follows; North Vietnam: 305,000 soldiers, 600 armored vehicles, and 490 heavy artillery pieces in South Vietnam and South Vietnam: 1.0 million soldiers,[2] 1,200 to 1,400 tanks, and more than 1,000 pieces of heavy artillery.[3]

The capital city of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, was captured by the Khmer Rouge on April 17. On December 2 the Pathet Lao took over the government of Laos, thus completing the communist conquest of the three Indochinese countries.

January

- 1 January

In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge attacked and drove back the government forces near Phnom Penh, the capital city. The Khmer Rouge now controlled 80 percent of the country and soon began attacking Phnom Penh, crowded with refugees, with rockets.[4]

- 6 January

Phước Bình, the capital of Phước Long Province, 120 kilometres (75 mi) north of Saigon, was captured by the North Vietnamese army, thus becoming the only provincial capital controlled by the North Vietnamese. All but 850 of 5,400 South Vietnamese soldiers defending the province were killed or captured. The lack of a military response by the US to the loss of a province persuaded North Vietnam that it could take more aggressive actions.[5]

- 8 January

Delegates to a Politburo conference in North Vietnam agreed that the US was not going to intervene militarily in South Vietnam and therefore North Vietnam had the opportunity to "destroy and disintegrate" the South Vietnamese army.[6]

- 11 January

The United States Department of State protested that North Vietnam had violated the 1973 Paris Peace Accord by infiltrating 160,000 soldiers and 400 armored vehicles into South Vietnam. North Vietnam had improved the Ho Chi Minh trail, now a network or all-weather roads, through Cambodia, and Laos and expanded their armament stockpiles.[7]

- 21 January

Asked at a press conference if there were circumstances under which the United States might again actively participate in the Vietnam War U.S. President Gerald Ford said, "I cannot foresee any at the moment."[8]

- 26 January

The last supply convoy from South Vietnam arrived via the Mekong River in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. Henceforth, Phnom Penh was isolated from any outside assistance except by air, effectively surrounded by the communist Khmer Rouge insurgents.[9]

- 28 January

President Ford asked Congress for an additional $522 million in military aid to assist South Vietnam and Cambodia. Ford said that North Vietnam now had 289,000 troops in South Vietnam and large numbers of tanks, artillery, and anti-aircraft weapons.[10]

February

- 5 February

North Vietnamese General Văn Tiến Dũng arrived in South Vietnam to take command of North Vietnamese armed forces. He decided that capture of the city of Ban Mê Thuột, the capital of Đắk Lắk Province, would be his first objective.[11]

March

- 4 March

North Vietnam began "Campaign 275" to capture the Central Highlands with diversionary attacks near Kon Tum and Pleiku while building up forces near Ban Me Thout, the main objective of the campaign.[12]

- 10 March

The North Vietnamese army launched its attack on Ban Me Thout. By nightfall the PAVN held the center of the city although fighting continued in the outskirts.[13]

- 12 March

The South Vietnamese commander, General Phạm Văn Phú, reported to his government that the North Vietnamese were firmly in control of Ban Me Thout.[14]

Captured in the PAVN assault on Ban Me Thout were 14 foreigners, including American missionaries with a six-year-old daughter and Paul Struharik, the provincial representative of the United States. The prisoners were marched to North Vietnam and held captive until being released on October 30. Their treatment was generally good.[15]

- 14 March

South Vietnamese President Thiệu met with his military commanders and unrealistically ordered General Phu to retake Ban Me Thout. All regular army forces were to be withdrawn from other parts of the Central Highlands to be reassembled for the assault on Ban Me Thout and for the defense of the coast.[16] The withdrawal was to be carried out with secrecy. U.S. authorities and South Vietnamese provincial leaders were not informed of this decision. The provincial forces, mostly Montagnard highlanders, were to be abandoned.[17]

- 15 March

Phu and his army abandoned efforts to retake Ban Me Thout and began the retreat to the coast.[18] ARVN's 23rd division at Ban Me Thout had been destroyed, with many desertions as South Vietnamese soldiers attempted to save themselves and their families, a pattern that would continue during the remainder of the war.[19]

- 16 March

The withdrawal of the army from the Central Highlands, mostly the troops stationed in the cities of Pleiku and Kon Tum, began. The only route open to many of the retreating ARVN forces was Route 7B, a highway in poor repair. As most senior officers of the army had departed the highlands by helicopter, many of the remaining soldiers were a leaderless mob mixed with fleeing civilians. In the "convoy of tears", under fire by the North Vietnamese, only about 60,000 of 180,000 fleeing civilians were known to have reached the coast and temporary safety. Only 900 of 7,000 South Vietnamese rangers, who provided most of the defense of the convoy, and 5,000 of 20,000 other Vietnamese soldiers are known to have survived. (Many of the soldiers probably deserted rather than report for duty.).[20]

- 19 March

Quảng Trị, the northernmost city of South Vietnam, was occupied by the North Vietnamese without a fight, the defenders having been evacuated by sea.[21]

- 24 March

North Vietnam changed the name of Campaign 275 to the "Ho Chi Minh Campaign." The original plan of North Vietnam had been to gain control over the Central Highlands of South Vietnam in 1975 and complete its conquest of the country in 1976. However, the rapid collapse of South Vietnamese defenses resulted in General Dung being given a more ambitious objective: the capture of Saigon before the birthday of Ho Chi Minh on May 19 and the onset of the rainy season at approximately the same date.[22]

- 25 March

After the fall of Quảng Trị, Hué, 60 kilometres (37 mi) south, was the next major city to fall to the North Vietnamese. The defenders were evacuated evacuated by sea. Both civilians and soldiers had begun abandoning the town several days earlier and headed south toward Da Nang, South Vietnam's second largest city.[23]

- 28 March

President Ford authorized the use of U.S. navy vessels to assist in the evacuation of South Vietnamese cities.[24]

- 29 March

Da Nang, 80 kilometres (50 mi) south of Hué, was the next domino to fall to communist forces. Crowded with a half million refugees, 70,000 people had been evacuated by barge or air during the previous several days. ARVN soldiers forced themselves onto the evacuation planes and barges and comprised a large share of the evacuees, but the 16,ooo soldiers evacuated were little more than 10 percent of the total ARVN force which had been stationed in northern Vietnam, military region 1.[25] The former US naval and air base of Cam Ranh Bay, almost 400 kilometres (250 mi) south, was the destination of most of the people evacuated.[26]

- 31 March

U.S. Army Chief of Staff Frederick C. Weyand in South Vietnam assessed the situation. "It is possible that with abundant resupply and a great deal of luck, the GVN [Government of South Vietnam] could survive...It is extremely doubtful that it could withstand an offensive involving the commitment of three additional Communist divisions...without U.S. strategic air support."[27] Col. William Le Gro of the U.S. Embassy said that without U.S. strategic bombing of North Vietnamese forces, South Vietnam would be defeated within 90 days.[28]

The North Vietnamese commander in South Vietnam, General Dung, was notified by his government that, due to the rapid collapse of South Vietnamese armed forces, he was to "liberate Saigon before the rainy season [mid-May]"[29] The original plan had been to wait until 1976 before attacking Saigon and the southern one-half of South Vietnam.

April

- 1 April

Qui Nhơn, South Vietnam's third largest city, 180 kilometres (110 mi) south of Da Nang, was captured by the North Vietnamese. More than one-half of the land area of South Vietnam was now under the control of the communists.[30]

Nha Trang was the next objective of the PAVN. General Phu, the commander of South Vietnamese forces in the northern part of the country, departed Nha Trang secretly by helicopter. Phu had previously promised to defend Nha Trang and had prohibited his soldiers from retreating. He did not inform his men or officers of his departure and order quickly broke down in the city.[31]

The American Consul General in Nha Trang, Moncrieff Spear, ordered the evacuation of American personnel from the city. In the hurried departure, about 100 of the Consulate's Vietnamese employees and one (out of five) Marine guard, Sgt. Michael A. McCormick, were left behind. McCormick was later able to leave Nha Trang on an Air America helicopter.[32]

Cambodian President Lon Nol and his family members fled Cambodia to go into exile in the United States. The Khmer Rouge had conquered most of Cambodia and were poised to capture the capital city of Phnom Penh.[33]

- 2 April

With the northern part of South Vietnam firmly in the hands of the PAVN after the west-to-east attacks, General Dung ordered most of his soldiers to turn south and drive toward Saigon, still 300 kilometres (190 mi) distant.[34]

- 3 April

U.S. President Gerald Ford announced Operation Babylift, a plan for the US to bring orphans from South Vietnam to the United States to be adopted by American parents.[35] During the next few weeks, 2,545 Vietnamese children would be flown out of the country of which 1,945 would come to the United States. 51 percent of the children were under 2 years old. 451 of the children were racially mixed, presumably the children of American and other soldiers who had been stationed in Vietnam. Operation Babylift was controversial as critics alleged that not all of the children were orphans and parents had not given their permission for their children to be adopted. There were also criticisms that the children were being removed from their own culture to save them from communist influences.[36]

U.S. General Weyand met with President Thiệu in Saigon. Weyand promised more American aid to South Vietnam, but declined Thiệu's request for a renewal of American bombing of North Vietnamese forces.[37]

South Vietnamese Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm resigned and made preparations to move to Paris, France.[38]

The Defense Intelligence Agency on the United States predicted that South Vietnam would be defeated in 30 days.[39]

- 4 April

The initial flight of Operation Babylift ended in disaster. The C-5 cargo plane carrying more than 300 persons, including children, escorts, and U.S. Air Force crew members crashed near Saigon. 78 Vietnamese children and 50 adults were killed.[40]

The first of two flights by the Royal Australian Air Force took place, in which Vietnamese civilians were evacuated to Bangkok and then to Australia.

- 5 April

The city of Nha Trang was captured with little opposition, the latest in a series of important cities to fall to the military forces of North Vietnam.[41] In less a month, the cities of Ban Mê Thuột, Quảng Trị, Hué, Da Nang, Qui Nhơn, and Nha Trang had fallen to the North Vietnamese army.

- 8 April

A South Vietnamese Air Force pilot dropped bombs on the Presidential Palace in Saigon and defected to the communist North Vietnamese. The bombs did little damage but caused panic in Saigon.[42]

- 9 April

The Battle of Xuân Lộc began. Xuân Lộc was a town 80 kilometres (50 mi) east of Saigon. South Vietnam had stationed most of its remaining mobile forces around the town to attempt to halt the drive of the North Vietnamese army toward Saigon.[43]

- 10 April

President Ford requested the U.S. Congress to provide additional aid to South Vietnam: $722 million for military and $250 million for economic aid. Congress declined to act on the President's request and expressed doubt that the aid could arrive in time to be useful—or, in any case, would enable South Vietnam to survive.[44]

- 17 April

The second and final flight by the RAAF of Vietnamese civilians to Bangkok took place for a total of 270 people evacuated as part of Operation Bablylift.[45]

Evacuation

- 12 April

The personnel of the American Embassy in Phnom Penh were evacuated in Operation Eagle Pull.[46] Fewer than 300 people were evacuated, including 82 Americans. Several American journalists and other foreigners chose to remain behind.[47]

Many prominent Cambodians chose to remain behind and trust to the mercies of the Khmer Rouge. Deputy Prime Minister Sisowath Sirik Matak said in a letter to the American Ambassador, "I cannot. alas, leave in such a cowardly fashion....I have only committed this mistake of believing in you, the Americans." Sirik Matak was executed a few days later by the Khmer Rouge.[48]

- 14 April

Two Congressional staff members, Richard Moose and Charles Miessner after visiting South Vietnam released a report stating that "no one including the Vietnamese military believes that more [U.S.] aid could reverse the flow of events." They said that evacuation of Americans from Saigon was being resisted by Ambassador Martin and other senior officials.[49]

- 16 April

The Foreign Ministry of North Vietnam announced that it would create "no difficulty or obstacles" to a U.S. evacuation of South Vietnam provided it was done "immediately."[50] .

- 17 April

The Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh without opposition. Immediately they ordered all the population, swollen to more than 2 million by refugees from the war, to evacuate the city.[51] The Khmer Rouge made no provision for food, shelter, and medical care for the evacuees and thousands died. The evacuated people were resettled in the countryside. Many educated people were summarily executed.[52]

A CIA spy within the inner circles of the North Vietnamese government told the U.S. Embassy in Saigon that North Vietnam would not negotiate but was committed to a military victory over South Vietnam before the end of April.[53]

- 18 April

President Ford, over the objections of Ambassador Graham Martin, ordered the evacuation of non-essential American employees of the U.S. in South Vietnam.[54] Martin feared that a U.S. evacuation would undermine confidence in the South Vietnamese government, cause panic, and possibly incite violence against Americans. Ford also created on this date the Interagency Task Force on Indochinese Refugees to evacuate Americans and Vietnamese from South Vietnam.[55]

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met with the USSR Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin. He presented a letter from President Ford requesting the Soviets to use their influence with North Vietnam to seek a cease fire in South Vietnam. In exchange, the US promised to withdraw from South Vietnam, cut off aid, and convene peace talks in Paris. Kissinger also warned that any North Vietnamese attacks against Saigon or Tan Son Nhat International Airport or interference with the U.S. withdrawal would cause a "most dangerous situation."[56]

- 19 April

With the battle of Xuân Lộc nearly over, and going in favor of North Vietnam, CIA director William Colby told the President that "South Vietnam faces total defeat -- and soon."[57]

- 21 April

The Battle of Xuân Lộc concluded with the South Vietnamese army retreating toward Saigon. Unlike earlier battles of the Spring Offensive, ARVN had put up a vigorous resistance to the attack of the North Vietnamese. Xuân Lộc was to be the last major battle of the Vietnam War. The North Vietnamese now controlled 2/3 of the territory of the country.[58]

President Thiệu of South Vietnam resigned, leaving the government in the hands of Vice President Trần Văn Hương. In his 2-hour resignation speech, Thiệu criticized the U.S. for not keeping its promises to Vietnam. He departed Vietnam in exile a few days later.[59] In response to Thiệu's resignation, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said that Thiệu's resignation "in all probability will lead to some form of negotiation" to save Saigon. However, all efforts to negotiate with North Vietnam proved fruitless.[60]

After a systematic evacuation of staff and dependents by the Royal New Zealand Air Force beginning two weeks prior, the last New Zealanders, including Ambassador Norman Farrell, were evacuated from the New Zealand Embassy in Saigon.[61]

- 22 April

The new President of South Vietnam, Trần Văn Hương, proposed a ceasefire in the fighting and negotiations between the South and the North. However, on this same day, North Vietnamese General Dung finalized his plans to conquer Saigon and issued orders to begin the operation.[62] The South Vietnamese army had approximately 60,000 soldiers to defend the city.[63] The North Vietnamese plan, with 130,000 soldiers, was to advance with its tanks and mechanized forces toward Saigon along main highways and capture key objectives in and around the city.[64]

The U.S. Department of Justice approved the entry into the United States of up to 130,000 Vietnamese refugees to be evacuated from South Vietnam.[65]

- 23 April

In a speech U.S. President Ford declared that the Vietnam War "is finished as far as America is concerned."[66]

In Saigon the evacuation of Americans and Vietnamese accelerated with two military transport airplanes per hour arriving at Ton Son Nhut airport on the outskirts of Saigon and 7,000 people per day being flown out of the country. The great majority of the Vietnamese evacuees were taken to Guam where they would be housed and processed for entry into the United States or other countries under Operation New Life. The military officer in charge of Operation New Life in Guam was Rear Admiral George Stephen Morrison, the father of rock singer Jim Morrison.[67]

- 24 April

A large U.S. Navy taskforce assembled off the coast of South Vietnam to assist in the evacuation. The ships of the task force would be the destination for those evacuated from Saigon by helicopter and the tens of thousands of South Vietnamese who were fleeing in private boats, barges, and Vietnamese naval vessels.[68]

- 25 April

The U.S. Embassy in Saigon decided that, to signal "Evacuation Day" for all Americans, the Defense's Attaché's radio station would broadcast the phrase "the temperature is 105 degrees and rising" followed by playing Bing Crosby's recording of the song White Christmas.

The last Australians including Ambassador Geoffrey Price of the Australian Embassy in Saigon were evacuated by the RAAF.

- 26 April

The assault on Saigon began with a North Vietnamese bombardment of Bien Hoa Air Base 30 kilometres (19 mi) northeast of Saigon. Biên Hòa was the largest fighter plane base is South Vietnam. It was quickly abandoned by South Vietnamese forces.[69]

- 27 April

The first North Vietnamese rockets fell in downtown Saigon, killing 6 people.[70]

President Hương resigned as President of South Vietnam. That evening the National Assembly named Dương Văn Minh, called "Big Minh", as President and gave him the job of "seeking ways and means to restore peace to South Vietnam."[71]

- 28 April

At 1730 hours Ton Son Nhut airport was bombed by North Vietnamese aircraft. With the runway damaged the refugee evacuation by fixed wing aircraft was interrupted.[72]

- 29 April

Rocket attacks by North Vietnamese forces on Ton Son Nhut airport began at 0358 hours and killed marines Charles McMahon and Darwin Judge the last two U.S. servicemen killed in combat in Vietnam (although two American helicopter pilots would die offshore in an accident during the evacuation[73]). McMahon and Judge served with the Marine Security Guard Battalion at the US Embassy, Saigon and were among the Marines providing security for evacuation of American personnel and South Vietnamese from Saigon.[74]

Offshore to assist with the evacuation were five U.S. aircraft carriers and more than 30 other U.S. navy ships. Tens of thousands of South Vietnamese attempted to evacuate South Vietnam by small boats and barges. By day's end, one of the U.S. ships had crowded more than 10,000 refugees on board and had been forced to refuse boarding to passengers of 70 or 80 other boats nearby.[75]

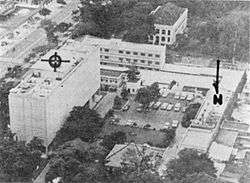

After a visit to Ton Son Nhut airport, Ambassador Martin and General Homer D. Smith, the highest ranking U.S. military officer in Vietnam, agreed that the situation was too dangerous to continue evacuating Americans and Vietnamese by fixed wing aircraft. Instead, a helicopter evacuation, dubbed Operation Frequent Wind, would begin immediately. The first evacuation by helicopter was about 1000 hours, although large-scale evacuation by helicopter did not begin until 1500 hours.[76]

By late afternoon, a mob of several thousand Vietnamese ringed the U.S. Embassy in downtown Saigon. Marine guards prevented them from climbing over the fence. Inside the Embassy compound were two to three thousand people, mostly Vietnamese, awaiting evacuation. This was far more people that the U.S. had anticipated evacuating from the Embassy and the Marine Corps commander of the helicopter evacuation assigned many additional helicopters to the evacuation. However, only one helicopter at a time could land at the Embassy in the parking lot and on the roof. After nightfall, wind and rain reduced visibility and made the helicopter landings hazardous. Embassy personnel set up a slide projector on the roof. The beam of light from the projector illuminated the landing area.[77]

Meanwhile, at the Defense Attaché's compound, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from the Embassy, evacuation by helicopter was also proceeding, although weather conditions and tracer rounds made the operation hazardous. At 2015 hours, General Smith boarded the last evacuation helicopter from the compound. The operation had evacuated more than 6,000 people, including more than 5,000 Vietnamese, by more than 100 helicopter sorties during the day. Meanwhile, the helicopter evacuation from the Embassy continued.[78]

About 2200 hours, Ambassador Martin at the Embassy, hearing that Washington planned to halt the evacuation. cabled the State Department: "I need 30 CH-53s [helicopters] and I need them now.[79]

In the Battle of Truong Sa or East Sea Campaign, a naval operation, North Vietnam completed its capture of the South Vietnamese-held Spratly Islands, 400 kilometres (250 mi) off the coast of Vietnam. Following the reunification of Vietnam in 1976, the Spratleys, Trường Sa in Vietnamese, became a part of Khánh Hòa Province.[80]

Hubert van Es was a Dutch photographer and photojournalist who took the well-known photo on 29 April 1975, which shows South Vietnamese civilians scrambling to board a CIA Air America helicopter during the U.S. evacuation of Saigon.[81]

The last diplomatic outpost of the U.S. outside Saigon was Cần Thơ in the Mekong Delta. At noon, despairing of other options for evacuation, Consul General Francis Terry McNamara assembled more than 300 U.S. Filipino, and Vietnamese employees of the U.S. government and loaded them on a barge and two landing craft and, under fire, set off down the river and out to sea. McNamara wore a helmet that declared he was the "Commodore, Can Tho Yacht Club." The group was picked up by a ship at 0100 the next morning.[82]

- April 30

Helicopter evacuations of Vietnamese and Americans continued from the Embassy until 0345. However, there were still about 420 Vietnamese and other non-Americans left inside the Embassy compound. Two additional helicopters were dispatched with the pilots instructed by President Ford that only Americans were to be evacuated. Ambassador Martin and his staff were to board the first of the helicopters and the remaining American staff were to leave on the second helicopter. Additional helicopters were then sent to evacuate the Marine guards, under the command of Major James Kean, with the last eleven leaving the Embassy at 0753 hours. Master Sergeant Juan Valdez was the last Marine to board the last helicopter out of Saigon. The 420 people awaiting evacuation were abandoned.[83]

Twenty-five years of U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam had ended.

South Vietnamese air force Major Buang landed a small Cessna airplane on the landing deck of the USS Midway. His wife and five children were aboard. American crew members applauded and took up a collection to help the family resettle in the U.S.[84]

AT 1024 hours, President Minh of South Vietnam announced on the radio the surrender of South Vietnam.[85]

About noon and almost unopposed, a column of tanks and armored vehicles of the North Vietnamese army advanced into downtown Saigon. A tank crashed through the gate of the Presidential palace. Inside, President Minh awaited the arrival of the North Vietnamese and surrendered. The soldiers of the South Vietnamese army had mostly abandoned their posts and the remainder of Saigon was captured with little opposition.[86]

The new communist government announced that Saigon had been renamed Ho Chi Minh City.[87]

May

- 5 May

General Vang Pao, a Hmong highlander, was ordered by the Prime Minister of Laos to cease resistance to the communist Pathet Lao. Vang Pao resigned instead.[88]

- 8 May

A few journalists and other foreigners had remained behind when the U.S. evacuated Phnom Penh. They were driven to the border with Thailand and expelled. The journalists reported that Phnom Penh was an empty city, except for Khmer Rouge soldiers, and that the country was a wasteland of ruins and abandoned towns and cities. Cambodia had become a land of silence with not even the names of its new rulers known to the outside world.[89]

- 12 May

Khmer Rouge forces seized the U.S. merchant vessel SS Mayaguez in the Gulf of Thailand, apparently without the knowledge of the central government of Cambodia.

- 13 May

The Pathet Lao and their North Vietnamese allies in Laos broke through the defense lines of the Hmong army headquartered in Long Tieng, "the most secret place on earth." " CIA agent Jerry Daniels organized an air evacuation of Vang Pao and about 2,000 Hmong, mostly soldiers and their families to Thailand.[90]

- 15 May

American armed forces re-captured the Mayaguez and rescued its crew. The U.S. launched retaliatory airs strikes against targets in Cambodia and landed Marines on Koh Tang island. The Marines encountered heavy resistance and 18 were killed before their withdrawal.[91] Twenty-three additional Americans were killed in a helicopter crash during the operation. [92]

- 23 May

Most American employees of the U.S. Embassy in Laos were ordered by their government to evacuate the country. Most were evacuated by air to Bangkok, Thailand. A skeleton staff remained at the Embassy.[93]

August

- 23 August

The King of Laos abdicated the throne. The communist Pathet Lao were already in control of the country.[94]

October

- 30 October

James Lewis a CIA agent captured near Phan Rang Air Base on 16 April 1975 and 13 other US prisoners captured during the 1975 Spring Offensive were transported by a UN-chartered C-47 from Hanoi to Vientiane, Laos and then on to Bangkok, Thailand.[95]

December

- 2 December

The Lao People's Democratic Republic was officially established.[96]

Bibliography

- Notes

- ↑ U.S Casualties, 1955–1975, accessed 21 Sep 2017

- ↑ Dougan, Clark and Fulghum, David (1985), The Fall of the South, Boston: Boston Publishing Company, p. 26. The total for South Vietnam includes an undetermined number of "ghost soldiers"--who existed only on paper.

- ↑ Isaacs, Arnold R. (1983), Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 333. Estimates of the military resources of both sides vary somewhat.

- ↑ Dougan and Fulghum, pp. 32–33

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 332–333

- ↑ Le Gro, Col. William E. (1985), Vietnam from Cease-Fire to Capitulation, Washington, D.C.; U.S. Army Center of Military History, p. 139

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 138

- ↑ "The President's News Conference", January 21, 1975, accessed 11 Sep 2017

- ↑ Daugherty, Leo (2011), The Vietnam War Day by Day, New York: Chartwell Books, p. 188

- ↑ Bowman, John S. (1985), The World Almanac of the Vietnam War, New York: Pharos Books, p. 343

- ↑ Langguth, A. J. (2000), Our Vietnam: The War 1954–1975, New York: Touchstone Books, p. 644

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 149

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 150

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 151

- ↑ Andelman, David. A. "14 Captives Freed by Vietnam Reds" The New York Times, October 31, 1975

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 151

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 348–351

- ↑ Langguth, p. 647

- ↑ Bowman, p. 343

- ↑ Editors of Boston Publishing Company (2014), The American Experience in Vietnam: Reflections on an Era, Boston: Zenith Press, p. 258

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 357

- ↑ Bowman, p. 343

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 357–361

- ↑ Bowman, p. 344

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, p. 90

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 363–369; Thompson, Larry Clinton (2010), Refugee Workers in the Indochina Exodus, 1975–1982 Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland Publishing Company, p. 9

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 171

- ↑ Dougan and Fulghum, p. 98

- ↑ Doughan and Fulgrhum p. 92

- ↑ Isaacs, pp 380–381; Bowman, p. 344

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 181

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 38; Dunham, George R. and Quinlan, David A. (1990), U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Bitter End, 1973–1975, History and Museums Division, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, Washingon, DC, pp. 131–132

- ↑ "Lon Nol, 72 dies, led Cambodia in early 1970s", The New York Times, accessed 13 Sep 2017

- ↑ Duiker, William J. (1996), The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, p. 345

- ↑ "Operation Babylift", accessed 12 Sep 2017

- ↑ "Agency for International Development, Operation Babylift Report, 1975", accessed 13 Sep 2017

- ↑ Langguth, p. 650

- ↑ Langguth, p. 650

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 171

- ↑ "Remembering the doomed first flight of Operation Babylift", accessed 13 Sep 2017

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 381

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, pp. 114–116

- ↑ Bowman, p. 344

- ↑ Issacs. pp. 407–409

- ↑ http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs243.aspx

- ↑ history.navy.mil (2000). "Chapter 5: The Final Curtain, 1973–1975". history.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 36

- ↑ Thompson, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, pp 126–127

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, pp 126–127

- ↑ Dougan and Fulghum, p. 124

- ↑ Webster's New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999, p. 321

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, p. 133

- ↑ Duiker, pp. 347–348

- ↑ Thompson, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Langguth, p. 655

- ↑ "Battle of Xuân Lộc" <http://vnafmamn.com/xuanloc_battle.html, accessed 13 Sep 2017

- ↑ Dougan, Clark and Fulghum, David (1985), The Fall of the South. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, p. 139

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 425-435

- ↑ https://vietnamwar.govt.nz/memory/fall-saigon

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 423, 425-426

- ↑ Willbanks, James H. (2004), Abandoning Vietnam: How America Left and South Vietnam Lost Its War, Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press, p. 257

- ↑ Duiker, p. 347; Doughan and Fulghum, p. 143

- ↑ Thompson, p. 14

- ↑ "A War that is Finished", The History Place, accessed 14 Sep 2017

- ↑ Thompson, p. 14, 62-63

- ↑ "Chapter 5: The Final Curtain, 1973–1975" Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 15 Sep 2017

- ↑ Le Gro, p. 177

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 438

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 439

- ↑ Smith, Homer D. (1975), "The Last 45 Days of South Vietnam" The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. p. 14, accessed 15 Sep 2017

- ↑ Bowman, p. 345.

- ↑ Smith, p. 13; Mather, Paul D. (1995), M. I. A.: Accounting for the Missing in Southeast Asia, Diane Publishing, p. 33

- ↑ Dougan and Fulghum, pp. 161, 163

- ↑ Smith, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Dougan and Fulghum, p. 167

- ↑ Dougan and Fulghum, pp 168–169

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, p. 169

- ↑ Thayer, Carlyle A. and Amer, Ramses (1999), Vietnamese foreign policy in transition, New York: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 69

- ↑ Lucas 2010

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 356, 362–363

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 471-477; The Vietnam War", episode 10, Public Broadcasting System

- ↑ "Navy History", accessed 22 Sep 2017

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, p. 175

- ↑ Isaacs, pp. 481-483

- ↑ Doughan and Fulghum, p. 177

- ↑ Thompson, p. 54

- ↑ Thompson, p. 45

- ↑ Thompson, pp 53–59

- ↑ Kutler, Stanley I., ed. (1996)m New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 2306–2307

- ↑ "year 1975 accidents". Helicopter Accidents. 23 December 2013.

- ↑ Thompson, p. 58

- ↑ Baird, Ian G. (2015), "1975: Rescalling our Understanding of the Fortieth Anniversary of the Establishment of the Lao People's Democratic Republic", Taylor and Francis Group, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2015.1095591, accessed 21 Sep 2017

- ↑ "14 Captives freed by Vietnam Reds". New York Times. 31 October 1975. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ↑ Baird

- References

- Lucas, Dean (2010). "Famous Picture: Vietnam Airlift". Famous Pictures Magazine. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- Mather, Paul D. (1995). M. I. A.: Accounting for the Missing in Southeast Asia (1995 ed.). DIANE Publishing. ISBN 0-7881-2533-8. - Total pages: 207

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- Dougan, Clark, David Fulghum, et al. e Fall of the SouthBoston: Boston Publishing Company, 1985.

| Vietnam War timeline |

|---|

|

↓HCM trail established ↓NLF Formed ↓Laos Bombing Begin ↓US Forces Deployed ↓Sihanouk Trail Created ↓PRG Formed │ 1955 │ 1956 │ 1957 │ 1958 │ 1959 │ 1960 │ 1961 │ 1962 │ 1963 │ 1964 │ 1965 │ 1966 │ 1967 │ 1968 │ 1969 │ 1970 │ 1971 │ 1972 │ 1973 │ 1974 │ 1975 |