Operation Thayer

Operation Thayer (13 September 1966 – 1 October 1966), Operation Irving (2 October 1966 – 24 October 1966) and Operation Thayer II (24 October 1966 – 11 February 1967) were related operations with the objective of eliminating communist People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and Viet Cong (VC) influence in Bình Định Province on the central coast of South Vietnam. The operations were carried out primarily by the United States 1st Cavalry Division against NVA and Viet Cong regiments believed to be in Binh Dinh. South Korean and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces also took part in the operation.

The sustained operations were deemed a success by the United States which claimed that more than 2,500 alleged PAVN/VC soldiers were thought to have been killed by American forces at a loss of about 300 American dead. Many areas under PAVN/VC influence were abandoned by the rural population as non-combatants fled the fighting or were forced by American and South Vietnamese forces to leave their homes. Though Operation Thayer was praised publicly, the US Military historian S.L.A. Marshall took a contrasting view privately, declaring that Operation Thayer was a "complete bust", that artillery was shooting at "clay pipes" and that the enemy was "either not there or so adroit and clever" as to completely avoid US search-and-destroy[1]. The PAVN/VC were able to break up into smaller units and evade open-battle against an overwhelming air-land-sea deployment of US forces, much like in Operation Masher which preceded it, they were able to return and contest the region once the operation had died down[2].

Background

Bình Định Province, on the central coast of South Vietnam, was a long-time communist stronghold with the VC, and increasingly the PAVN, controlling most of the rural areas. Bình Định, with a population of about 875,000, was characterized by a heavily-populated narrow coastal plain out of which rose several mountain massifs. Inland, the many rivers ran through narrow valleys separated by heavily-forested mountains.[3] The area of the province was 2,326 square miles (6,020 km2). The ARVN controlled little more than the larger towns and Highway 1, the main north-south thoroughfare of South Vietnam, and Highway 19 which led from the coast to the highland city of Pleiku.

The 1st Cavalry Division began operations against VC and PAVN forces in Bình Định shortly after its arrival in South Vietnam in September 1965. From its base at Camp Radcliff near An Khe, the 1st Cavalry had launched operations several operations into nearby Bình Định Province which resulted in large numbers of PAVN/VC soldiers being killed in search and destroy missions, but, with the withdrawal of U.S. forces from the province after each incursion, the PAVN/VC quickly reestablished their control or influence over many rural areas in the province.

On the night of 3 September 1966 a VC platoon launched a mortar attack on Camp Radcliff. The base was hit by 119 mortar rounds over a 5-minute period, killing 4 soldiers and wounding 76, while 77 out of the 1st Cavalry's 400-plus helicopters were damaged. The VC were believed to have escaped.[4] In early September, the PAVN and VC also attacked several ARVN military bases and ambushed an ARVN convoy. The attacks illustrated the fragility of the control of the area by the South Vietnamese government and the need to suppress the PAVN/VC forces.[3]:219–20

Operation Thayer and follow-on operations Irving and Thayer II were called the "Binh Dinh Province Pacification Campaign" and had the objective "to clean up, once and for all, all regular VC and PAVN units in the area as well as uprooting the long established VC infrastructure."[5]

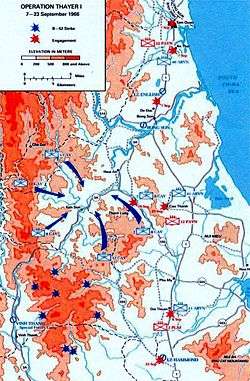

Operation Thayer

Operation Thayer was the largest air assault undertaken up until that time in the Vietnam War.[5] The focus of Operation Thayer was the Kim Son Valley where seven small rivers, separated by mountains, came together in what the Americans called the Crow's Foot. the 1st Cavalry had previously encountered stiff resistance in the Crow's foot during Operation Masher in February 1966. It now appeared that the PAVN/VC had re-established their base areas.[3]:209 After two days of B-52 air strikes near the valley, on 13–14 September General John Norton airlifted 5 battalions into the highlands surrounding the Kim Son valley. The Americans then descended into the valleys, hoping to catch large numbers of PAVN/VC in their net. They found few enemies to fight, but determined that the communist forces in the Kim Son valley had escaped to the east.[3]:257–9

Operation Thayer ended October 1. The Americans claimed to have killed 231 communist soldiers at a loss to themselves of 35 dead and missing.[3]:261 Contrasting the success of this operation, was S.L.A. Marshall assessing that Operation Thayer had wasted the energy of those involved, and that from first-hand observation stated that 231 killed was a complete fabrication[1].

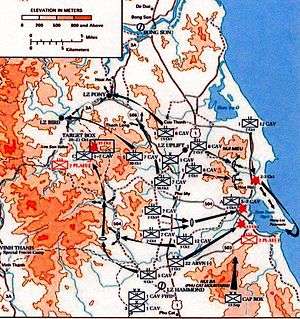

Operation Irving

Operation Irving immediately followed Operation Thayer. The focus of the American offensive moved east to the small mountain ranges near the coast of Bình Định where the PAVN 12th Regiment which had fled the Kim Son Valley was believed to be. To "find, fix, and finish" the PAVN Norton had five American, five South Korean, and 2 South Vietnamese battalions, a total of some 6,000 men. Each national contingent would search a different mountain massif rising more than 1,000 feet (300 m) out of the coastal plain over a north-south area of more than 15 miles (24 km) and extending more than 5 miles (8.0 km) inland from the sea.[3]:262 The allied forces attempted to prevent the communist forces from exfiltrating this area.

A problem faced in Operation Irving was the large number of non-combatants, mostly farmers, in the heavily-populated coastal area. Leaflets and radio programs instructed the civilians to stay put in their villages or if caught in a battle for the village to leave only in the direction of allied soldiers.[5]

Battle of Hoa Hoi. Operation Irving had an immediate success on October 2. The Americans observed communist soldiers in the village of Hoa Hoi, near the coast, and sent in by helicopter a platoon-sized group to investigate. The platoon took heavy fire and suffered casualties and reinforcements were rushed to the area to encircle the village. Villagers were offered the opportunity to leave Hoa Hoi and about 200 did. Nightfall came before an attack could be organized. The U.S. Navy offshore fired illumination shells all night to prevent the PAVN from escaping through the American lines.

The next morning two American companies advanced on the village from the north, forcing the PAVN to either stand and fight or to attempt to break through the Americans lines encircling the village. The American attackers searched and destroyed the village and rooted out the PAVN. By the end of the day, the battle was over. The Americans claimed to have killed 233 soldiers and taken 35 prisoners out of a total PAVN force of 300 men. American losses were six dead.[3]:263–9

Following the successful Hoa Hoi battle, the 1st Cavalry searched for additional PAVN/VC forces, shifting the focus westward to the mountainous Kim Son and Suoi Ca valleys. The South Korean and South Vietnamese forces also clashed with the Viet Cong and the PAVN, the South Vietnamese, with U.S. helicopter gunship support, accounting for 135 communist soldiers in a battle on 13 September. The allied forces, however, could not find and bring to battle large elements of the enemy.[3]:269–71

Operation Irving was declared a great success, with the allies claiming they had killed 681 PAVN/VC (body count) and captured 1,409 with losses to the allies of 52 dead[6]. The Americans accounted for 681 of those killed while suffering 19 dead.[3]:272 The success of this operation contrasted with previous ones, as this was described as "result of a fluke shot" rather than a deliberate search and destroy, noting the previous battles in which the U.S rarely had tactical or strategic initiative against the NVA/VC[1].

Operation Thayer II

_is_having..._-_NARA_-_530612.tif.jpg)

Operation Thayer was focused on searching the Kim Son valley and southwards to the Soui Ca Valley for communist forces, which were believed to have broken into smaller units due to the successes of Operation Irving. The operation was hampered by heavy monsoon rains which impacted both American and PAVN/VC forces. In early December the decision was taken to empty the Kim Son Valley of its non-combatants and declare it a free fire zone in which any unidentified person was considered to be a combatant and unrestricted artillery and air strikes were permitted. About 1,100 people were forced or enabled to leave the valley. Many others chose to stay, either because they were Viet Cong loyalists or refused to abandon their homes and land. On December 17, American forces fought a battle east of the Kim Son valley, killing 95 PAVN/VC at a cost of 34 American dead and three helicopters shot down.[7][5]

Firebase Bird. The PAVN/VC forces demonstrated they were still capable of offensive action with an attack on Firebase Bird in the contested Kim Son Valley on 26 December. The Firebase had been hurriedly constructed and, due to a Christmas truce, had less than one-half of its authorized manpower present. The PAVN/VC nearly overran the firebase before being repelled by "beehive' rounds (containing thousands of tiny metal arrows) and helicopter gunships. The 1st Cavalry sent in a battalion of troops to pursue the retreating attackers. U.S. losses in the attack were more than 60 percent of the defenders of Firebase Bird, with 27 dead and 67 wounded. The U.S. estimated that PAVN/VC losses in the attack and pursuit were 267 dead.[7]:89–92

During the remainder of Operation Thayer II the 1st Cavalry consolidated and strengthened its positions in Bình Định Province, preparing for Operation Pershing, another major operation to begin at the end of the Têt truce from 8 to 12 February. The U.S. claimed to have killed 1,757 PAVN and VC combatants during Thayer II and to have driven out of Bình Định Province one regiment and severely damaged two more. 242 Americans were killed, and 947 wounded.[8][7]:179–182

Refugees

Operations Thayer, Irving, and Thayer II displaced a large number of people in Bình Định Province. At the end of 1966, the province had 85 refugee camps with a reported population of 129,202. Additional people displaced by the war crowded into towns and villages or lived as squatters along Highway 1. About one-third of the 875,000 people of Bình Định were displaced in 1966 by the war. In some instances the displacement of people by the U.S. and South Vietnam was deliberate, forcing people to leave the Kim Son and An Lao valleys and declaring them free fire zones.[8]:58–9

While the U.S. portrayed the refugee movement as people "fleeing communism", U.S. Department of Defense studies showed that the most important cause of refugees was U.S. and South Vietnamese "bombing and artillery fire, in conjunction with ground operations."[8]:109 The response of the governments of South Vietnam and the U.S. to meet the needs of the refugees was inadequate. The refugee camps themselves were often hotbeds of discontent and VC activity. Some refugee camps were considered unsafe for South Vietnamese government officials to visit without military escorts.[9]

The generation of refugees was considered a sign of progress in the war to some in the U.S. "The influx [of refugees] has had the favorable effect of denying the VC a needed labor and agricultural force, and of decreasing the manpower base from which to impress recruits" said a U.S. Marine Corps report. The U.S. Department of State suggested that the generation of refugees might be a good idea in some cases. However, another Department of Defense report said that "Refugee movement is highly visible evidence of the failure of the government to protect the rural population from the Viet-Cong."[8]:111–2

References

![]()

- 1 2 3 Appy, Christian G. (2000-11-09). Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 9780807860113.

- ↑ Rosen, Stephen Peter (1994). Winning the Next War: Innovation and the Modern Military. Cornell University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0801481961.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Carland, John (2000). Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966. Government Printing Office. p. 201-2. ISBN 9781782663430.

- ↑ "After Action Report (3 Sep 1966 attack on Camp Radcliff)" (PDF). U.S. Army. 17 September 1966. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Publication, 1st Cavalry Division Association – Interim Report of Operations, First Cavalry Division, July 1965 to December 1966", ca. 1967, Folder 01, Box 01, Richard P. Carmody Collection". The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Willbanks, James H. (2013-09-03). Vietnam War Almanac: An In-Depth Guide to the Most Controversial Conflict in American History. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 1966. ISBN 9781626365285.

- 1 2 3 MacGarrigle, George L. (1998). Taking the Offensive: October 1966 to October 1967. Center of Military History, United States Army. pp. 87–89. ISBN 9781780394145.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewy, Guenter (1978). America in Vietnam. Oxford University Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0195027327.

- ↑ Krepinevich, Andrew F. (1986). The Army and Vietnam. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 226. ISBN 9780801836572.