1968 in the Vietnam War

| 1968 in the Vietnam War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cholon after Tet Offensive operations 1968 | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||||

| Strength | |||||

|

US: 549,500 [1] | NVA/VC: 420,000 [5] | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

|

US: 16,592 killed [6] 87,388 wounded[7] South Vietnam: 27,915 killed [8] 172,512 wounded[7] |

US estimates: 191,000 [9] - 208,254 killed [5][A 1]) North Vietnamese Records:KIA: 44,824 Total KIA/WIA: 111,306 Killed and Wounded,[11] | ||||

The year 1968 saw major developments in the Vietnam War. The military operations started with an attack on a US base by the Vietnam People's Army (NVA) and the Viet Cong on January 1, ending a truce declared by the Pope and agreed upon by all sides. At the end of January, the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong launched the Tet Offensive.

Hanoi erred monumentally in its certainty that the offensive would trigger a supportive uprising of the population. NVA and Viet Cong troops throughout the South, from Hue to the Mekong Delta, attacked in force for the first time in the war, but to devastating cost as ARVN and American troops killed close to 60,000 of the ill-supported enemy in less than a month. These reversals on the battlefield (the Viet Cong would never again fight effectively as a cohesive force) failed to register on the American home front, however, as shocking photos and television imagery, and statements such as Conkrite's, fueled what would ultimately prove to be a propaganda victory for Hanoi.

Peter Arnett quoting an unnamed US major as saying, "It became necessary to destroy the town to save it." Eddie Adams' iconic image of South Vietnamese General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan's execution of a Vietcong operative was taken in 1968. The year also saw Walter Cronkite's call to honourably exit Vietnam because he thought the war was lost. This negative impression forced the US into the Paris peace talks with North Vietnam.

US troop numbers peaked in 1968 with President Johnson approving an increased maximum number of US troops in Vietnam at 549,500. The year was the most expensive in the Vietnam war with the American spending US$77.4 billion (US$ 544 billion in 2018) on the war. The year also became the deadliest of the Vietnam War for America and its allies with 27,915 South Vietnamese (ARVN) soldiers killed and the Americans suffering 16,592 killed compared to around two hundred thousand of the communist forces killed. The deadliest week of the Vietnam War for the USA was during the Tet Offensive specifically February 11–17, 1968, during which period 543 Americans were killed in action, and 2547 were wounded.

January

- January 1

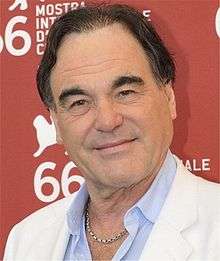

The People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) violated a New Year's truce. At the New Year's Day Battle of 1968 among the Americans were future writer Larry Heinemann and future film director Oliver Stone.[12][13]

In Newsweek magazine Robert Komer touted the early success of the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS) pacification program he led. He said that "only one South Vietnamese in six now lives under VC [Viet Cong] control."[14]

- 19 January

In the first two weeks of 1968, communist forces shelled 49 district and provincial capitals in South Vietnam and temporarily occupied two of them. The Commander of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) General William Westmoreland described to Time the fighting "as the most intense of the entire war." MACV claimed that 5,000 communist forces had been killed.[15]

- 21 January

The long and bloody Battle of Khe Sanh began with an assault by the PAVN on a hill held by U.S. Marines. Khe Sanh is in northwestern Quảng Trị Province, near the Demilitarized Zone. The combatants were elements of the U.S. III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) against two to three PAVN division-size elements.[16] NVA General Vo Nguyen Giap later explained that his objective was to create a diversion to draw U.S. forces away from the populated areas of South Vietnam. Khe Sanh diverted 30,000 US troops away from the cities that would be the main targets of the Tet Offensive.[17]

- January 23–24, 1968

Battle of Ban Houei Sane began on the night of 23 January 1968, when the 24th Regiment of the PAVN 304th Division overran the small Laotian Army outpost at Ban Houei Sane.[18]

- January 24 − March 1

Operation Coburg was an Australian military action that saw heavy fighting between the 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF) and PAVN and Viet Cong forces during the wider fighting around Long Binh and Biên Hòa.[19]

- 26 January

In Time Magazine, General Westmoreland said, "the Communists seem to have run temporarily out of steam."[20]

- 28 January

General Westmoreland in his annual report said "In many areas the enemy has been driven away from the population centers; in others he has been compelled to disperse and evade contact thus nullifying much of his potential. The year ended with the enemy increasingly resorting to desperation tactics in attempting to achieve military/psychological victory; and he has experienced only failure in those attempts."[21]

Tet Offensive

- January 29

At half-past midnight on Wednesday morning the North Vietnamese launch the Tet Offensive at Nha Trang. At 2:45 that morning the US Embassy in Saigon is attacked.[22]

- January 31 – March 7

The Battle of Saigon was the coordinated attack by communist forces, including both the PAVN and the Viet Cong, against Saigon.[23]

- January 30 – March 3

The Battle of Huế was one of the bloodiest and longest battles. With massive air support the ARVN and three understrength U.S. Marine battalions attacked and defeated more than 10,000 entrenched PAVN and Viet Cong.[24]

- February 1, 1968

One notable ARVN unit, the 3d Armored Cavalry Squadron, fought a pitched battle with the Viet Cong's H-15 Local Force Battalion near Pleiku.[25] They were later awarded the United States Presidential Unit Citation for extraordinary heroism against hostile forces during the Tet Offensive, making them one of only a few non-U.S. military units to receive the highest U.S. military honor awarded at the unit level. [26]

February

- February 1

During South Vietnamese action following the first day of the Tet Offensive General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan is captured on film executing a Viet Cong prisoner by American photographer Eddie Adams. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph becomes yet another rallying point for anti-war protesters.[27]

- February 6 - February 7

The Battle of Lang Vei was fought on the night of 6 February 1968, between elements of the PAVN, supported by PT-76 light tanks and the United States-led Detachment A-101, 5th Special Forces Group.[18]

- February 7

International reporters arrive at the embattled city of Bến Tre in South Vietnam. Peter Arnett, then of the Associated Press, writes a dispatch quoting an unnamed US major as saying, "It became necessary to destroy the town to save it."[28]

- February 18

During the week of February 11–17, 1968 the record for the highest US casualty toll during one week was set. The record coming off after the Tet Offensive was 543 Americans killed in action, and 2547 wounded.[29]

- February 27

Walter Cronkite, reporting after his recent trip to Vietnam for his television special "Who, What, When, Where, Why?" gives a highly critical editorial and urges America to leave Vietnam "...not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could."[30]

March

- March 10 – March 11

Battle of Lima Site 85 was a battle for control of a secret radar site at Phou Pha Thi, Laos.[31]

- March 15

In Quảng Trị Province, just of the DMZ, the 3rd Marine Division begins Operation Scotland II to drive the North Vietnamese out of the province's western third, which takes it 10 months.

- March 16

US ground troops from Charlie Company of 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division (the Americal Division) carry of the My Lai Massacre killing more than 500 Vietnamese civilians from infants to the elderly. The event would remain buried for more than a year.[32]

- March 31

President Lyndon Johnson addresses the nation, announcing steps to limit the war in Vietnam and reporting his decision not to seek reelection. The speech announces the first in a series of limitations on US bombing, promising to halt these activities above the 20th parallel.[33]

United States Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford gets the President to authorize 24,500 more troops on an emergency basis, raising authorized strength to the Vietnam War's peak of 549,500, a figure never reached.[1]

April

- April 8 - May 31

Operation Toan Thang I was a US and ARVN operation conducted between 8 April 1968 and 31 May 1968. Toan Thang, or "Complete Victory", was part of a reaction to the Tet Offensive by forces allied with the Republic of Vietnam designed to put pressure on Vietcong and PAVN]] forces.[34]

- April 19 - May 17

Operation Delaware was a military operation in the A Shau Valley. The A Shau Valley was an important corridor for moving supplies into South Vietnam and used as staging area for attacks. American and South Vietnamese had not been present in the area since the Battle of A Shau, when a Special Forces camp located there was overrun.[34]

May

- May 5

May Offensive was launched in the early morning hours of 4 May, in which communist units initiated PHASE II of the Tet Offensive of 1968 (also known as the May Offensive, "Little Tet", and "Mini-Tet") by striking 119 targets throughout South Vietnam, including Saigon.[35][36]

- May 10–12, 1968

The Battle of Kham Duc was the struggle for the United States Army Special Forces camp located in Quảng Tín Province, South Vietnam. The camp was occupied by the 1st Special Forces detachment consisting of U.S. and South Vietnamese special forces, as well as Montagnard irregulars.[37]

- May 12 – June 6

The Battle of Coral–Balmoral was a series of actions fought between the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) and communist forces, north-east of Saigon.[38]

- May 13

The first US and North Vietnamese delegations meet at the Paris peace talks to discuss American withdrawal.[39]

October

- October 8

Operation Sealords was launched on October 8, 1968, and was intended to disrupt North Vietnamese supply lines in and around the Mekong Delta. As a two-year operation, by 1971 all aspects of Sealords had been turned over to the South Vietnam Navy.[40]

- October 31

President Johnson announces a total halt to US bombing in North Vietnam.[41]

November

- November 1

After three-and-a-half years, Operation Rolling Thunder comes to an end. In total, the campaign had cost more than 900 American aircraft. Eight hundred and eighteen pilots are dead or missing, and hundreds are in captivity. Nearly 120 Vietnam People's Air Force planes have been destroyed in air combat, accidents, or by friendly fire. According to U.S. estimates, 182,000 North Vietnamese civilians have been killed. Twenty thousand Chinese support personnel also have been casualties of the bombing.[42]

- November 5

Richard Nixon wins the 1968 presidential election in America. The results of the popular vote are 31,770,000 for Nixon, 43.4 percent of the total; 31,270,000 or 42.7 percent for Humphrey; 9,906,000 or 13.5 percent for Wallace; and 0.4 percent for other candidates.[43][44]

December

- December 1968 to May 11, 1969

Operation Speedy Express was a controversial United States military operation conducted in the Mekong Delta provinces Kien Hoa and Vĩnh Bình. The operation was launched to prevent Viet Cong units from interfering with pacification efforts and to interdict lines of Viet Cong communication and deny them the use of base areas.[34]

- December 12, 1968 – March 9, 1969

Operation Taylor Common was a search and destroy operation conducted by Task Force Yankee, a task organized force of the 1st Marine Division. The objective was to clear the An Hoa Basin, neutralize the PAVN's Base Area 112 and develop Fire Support Bases (FSBs) to interdict Communist infiltration routes leading from the Laotian border.[34]

Year in numbers

| Armed Force | Strength | KIA | Reference | Military costs - 1968 | Military costs in 2018 US$ | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 820,000 | 27,915 | [2][8] | |||||

| 549,500 | 16,592 | [6] | US$77,350,000,000 | US$ 544,336,750,000 | [45] | ||

| 50,000 | [3][4] | ||||||

| 6000 | [4] | ||||||

| 7660 | [4] | ||||||

| 1580 | [4] | ||||||

| 520 | [4] | ||||||

| 420,000 [5] | North Vietnamese Source: 44,824

191,000 - 208,254 (US estimates) |

[5][9][46] |

Annotations

Bibliography

- Notes

- 1 2 United States Department of Defense 2010

- 1 2 "Facts about the Vietnam Veterans memorial collection". NPS.gov. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- 1 2 Leepson & Hannaford 1999, p. 209

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

War Remnants Museum Data

Armed Force 1910 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972

514,000 643,000 735,900 798,800 820,000 897,000 968,000 1,046,250 1,048,000

23,310 180,000 385,300 485,600 549,500 549,500 335,790 158,120 24,000

200 20,620 25,570 47,830 50,000 48,870 48,540 45,700 36,790

200 1560 4530 6820 7660 7670 6800 2000 130

0 20 240 2220 6000 11,570 11,570 6000 40

20 70 2060 2020 1580 190 70 50 50

30 120 160 530 520 550 440 100 50 - 1 2 3 4 Smith 2010

- 1 2 United States 2010

- 1 2 http://www.rjsmith.com/kia_tbl.html

- 1 2 Smedberg 2008, p. 196

- 1 2 Asprey 2002, p. 914

- ↑ Joes 2001, p. 99

- ↑ http://www.nhandan.com.vn/chinhtri/item/7976502-.html

- 1 2 Gaijinass (February 27, 2010). "Platoon: The story of Oliver Stone in Vietnam". gaijinass. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Bates 1996, p. 106

- ↑ Asprey, Robert B. (1994), War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History, New YorK: William Morrow and Company, p. 871

- ↑ Asprey, Robert P. (1994), War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History, New York: William Morrow and Company, p. 896

- ↑ Clarke, Bruce B. G. (2007), Expendable warriors: the Battle of Khe Sanh and the Vietnam War, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 69

- ↑ Page, Tim and Pimlott, John Pimlott (1990), Nam – The Vietnam Experience, 1965-75, London: Hamlyn, p. 324

- 1 2 Cash 1985, p. 111

- ↑ McNeill & Ekins 2003, p. 290

- ↑ Asprey, p. 896

- ↑ Asprey, p. 872

- ↑ Will banks 2008, pp. 34–36

- ↑ Watson & Oberholtzer 2010, p. 1

- ↑ Stanton 2003, p. 11

- ↑ "ARVN 3rd Cavalry Squadron fought a pitched battle". Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ↑ "3d Armored Cavalry Squadron (ARVN) earned Presidential Unit Citation (United States) for extraordinary heroism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ↑ Lucas 2010

- ↑ New York Times 1968, p. 14

- ↑ AP 1968, p. 3

- ↑ Arnold 1990, p. 88

- ↑ Kelly 1996, p. 191

- ↑ Olson & Roberts 1998, p. 162

- ↑ Hamilton-Merritt 1993, p. 187

- 1 2 3 4 Stanton 2003, p. 12

- ↑ Nolan 2006, p. 21

- ↑ Davies & McKay 2005, p. 122

- ↑ Davies 2008, p. 169

- ↑ McAulay 1989, p. 777

- ↑ Hixson 2000, p. 274

- ↑ History.com 2010

- ↑ Hixson 2000, p. 280

- ↑ PBS (2010). "Battlefield Timeline". Public Broadcast Service. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ Boyer et al., p. 696

- ↑ Brune & Burns 2003, p. 775

- ↑ Johnson 2004, p. 56

- ↑ "Tết Mậu Thân 1968 qua những số liệu". Tết Mậu Thân 1968 qua những số liệu (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- References

- AP (Feb 21, 1968). "U.S. war toll sets record". Toledo Blade. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Arnold, James R. (1990). Tet Offensive 1968: turning point in Vietnam (1990 ed.). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-960-9. - Total pages: 96

- Asprey, Robert B. (2002). War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History, Volume 2 (2002 ed.). iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-22594-1. - Total pages: 1281

- Bates, Milton J. (1996). The wars we took to Vietnam: cultural conflict and storytelling (1996 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20433-1. - Total pages: 328

- Boyer, Paul S.; Clark, Clifford; Hawley, Sandra; Kett, Joseph F.; Rieser, Andrew (2009). The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People, Volume 2: From 1865, Concise Volume 2 of The Enduring Vision (2009 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-547-22278-3. - Total pages: 496

- Brune, Lester H.; Burns, Richard Dean (2003). Chronological History of U.S. Foreign Relations: 1932-1988 (2003 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93916-4. - Total pages: 1549

- Cash, John A. (1985). Seven Firefights in Vietnam (1985 ed.). DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56806-563-2. - Total pages: 159

- Clarke, Bruce B. G. (2007). Expendable warriors: the Battle of Khe Sanh and the Vietnam War (2007 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99480-8. - Total pages: 167

- Davies, Bruce (2008). The Battle at Ngok Tavak: a bloody defeat in South Vietnam, 1968 (2008 ed.). Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-064-5. - Total pages: 250

- Davies, Bruce; McKay, Gary (2005). The men who persevered: the AATTV, the most highly decorated Australian unit of the Viet Nam War (2005 ed.). Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-425-3. - Total pages: 418

- Hamilton-Merritt, Jane (1993). Tragic mountains: the Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942-1992 (1993 ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20756-2. - Total pages: 580

- History.com (2010). "U.S. and South Vietnamese navies commence Operation Sealords". History.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- Hixson, Walter L. (2000). Leadership and diplomacy in the Vietnam War (2000 ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-3533-7. - Total pages: 354

- Joes, Anthony James (2001). The war for South Viet Nam, 1954-1975 (2001 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96807-6. - Total pages: 199

- Johnson, Chalmers A. (2004). The sorrows of empire: militarism, secrecy and the end of the republic (2004 ed.). Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-578-3. - Total pages: 389

- Kelly, Orr (1996). From a dark sky: the story of U.S. Air Force Special Operations (1996 ed.). Presidio. ISBN 978-0-89141-520-6. - Total pages: 340

Leepson, Marc; Hannaford, Helen (1999). Webster's new world dictionary of the Vietnam War (1999 ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-862746-5. - Total pages: 598

- Lucas, Dean (2010). "Vietnam Execution". Famous Pictures Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- McAulay, Lex (1989). The Battle of Coral: Vietnam fire support bases Coral and Balmoral, May 1968 (1989 ed.). Arrow Australia. ISBN 978-0-09-169721-1. - Total pages: 361

- McNeill, Ian; Ekins, Ashley (2003). On the offensive: the Australian Army in the Vietnam War, January 1967-June 1968 (2003 ed.). Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86373-304-5. - Total pages: 650

- Nolan, Keith W. (2006). House to House: Playing the Enemy's Game in Saigon, May 1968 (2006 ed.). Zenith Imprint. ISBN 978-0-7603-2330-4. - Total pages: 368

- Olson, James Stuart; Roberts, Randy (1998). My Lai: a brief history with documents (1998 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-17767-6. - Total pages: 222

- Smedberg, Marco (2008). Vietnamkrigen: 1880–1980 (2008 ed.). Historiska media. ISBN 978-91-85507-88-7. - Total pages: 361

- Stanton, Shelby L. (2003). Vietnam order of battle (2003 ed.). Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0071-9. - Total pages: 396

- "Major Describes Move". The New York Times. February 8, 1968. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- Smith, Ray (2010). "Casualties - US vs NVA/VC". rjsmith.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Willbanks, James H. (2008). The Tet Offensive: A Concise History (2008 ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12841-4. - Total pages: 264

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- United States Department of Defense (2010). "Clark M. Clifford". United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- Watson, Andy, Historian, U.S. Army Military Police School; Oberholtzer, William A. (2010). "Looking Back in History:The Battle of Saigon Forty Years Ago" (PDF). United States Army:Fort Leonard Wood. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

| Vietnam War timeline |

|---|

|

↓HCM trail established ↓NLF Formed ↓Laos Bombing Begin ↓US Forces Deployed ↓Sihanouk Trail Created ↓PRG Formed │ 1955 │ 1956 │ 1957 │ 1958 │ 1959 │ 1960 │ 1961 │ 1962 │ 1963 │ 1964 │ 1965 │ 1966 │ 1967 │ 1968 │ 1969 │ 1970 │ 1971 │ 1972 │ 1973 │ 1974 │ 1975 |