1962 Tour de France

Route of the 1962 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 24 June – 15 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 22, including two split stages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,274 km (2,656 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 114h 31' 54" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1962 Tour de France was the 49th edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. The 4,274-kilometre (2,656 mi) race consisted of 22 stages, including two split stages, starting in Nancy on 24 June and finishing at the Parc des Princes in Paris on 15 July. After more than 30 years, the Tour was contested again by trade teams. Jacques Anquetil of the Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson team defended his title to win his third Tour de France. Jef Planckaert (Flandria–Faema–Clément) placed second, 4 min and 59 s in arrears, and Raymond Poulidor (Mercier–BP–Hutchinson) was third, with a loss of over ten minutes.

Anquetil's teammate Rudi Altig took the first race leader's yellow jersey after winning the first stage. Altig lost it the following day to André Darrigade of Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani, who won stage 2a, before regaining after winning stage three. The lead was taken by Albertus Geldermans (Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson) after stage six. He held it for two stages, before Darrigade took it back for the next two. Flandria–Faema–Clément rider Willy Schroeders then led the race between the end of stage nine to the end of eleven. The following day, British rider Tom Simpson (Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani) became the first rider from outside mainland Europe to wear the yellow jersey. He lost it to Planckaert after stage thirteen's individual time trial to Superbagnères in the Pyrenees. He held the lead for seven stages, which included the Alps. Anquetil's victory in the individual time trial of stage twenty put him in the yellow jersey, which he held until the conclusion of the race.

In the other race classifications, Altig won the points classification and Federico Bahamontes of Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro won the mountains classification. The team classification was won by Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson, and Eddy Pauwels (Wiel's–Groene Leeuw) won the award for most combative rider. Altig and Emile Daems (Philco) won the most stages, with three each.

Teams

.jpg)

From 1930 to 1961, the Tour de France was contested by national teams, but in 1962 commercially sponsored international trade teams returned.[1][n 1] From the late-1950s to 1962, the Tour had seen the absence of top riders who had bowed to pressure from their team's extra-sportif (non-cycling industry) sponsors to ride other races that better suited their brands.[3][4] This, and a demand for wider advertising from a declining bicycle industry, led to the reintroduction of the trade team format.[5][6]

In the beginning of February 1962, 22 teams submitted applications for the race,[7] with the final list of 15 announced at the end of the month. The Spanish-based Kas was the first choice reserve team.[8] Each of the 15 teams consisted of 10 cyclists (150 total),[9][10] an increase from the 1961 Tour, which had 11 teams of 12 cyclists (132 total).[11] Each team was required to have a dominant nationality; at least six cyclists should have the same nationality, or only two nationalities should be present.[12][13] For the first time, the French cyclists were outnumbered; the largest numbers of riders from a nation were Italians at 52, with the next largest coming from cyclists France (50) and Belgium (28). Riders represented a further six nations, all European.[10]

Of start list of 150,[n 2] 66 were riding the Tour de France for the first time.[16] The total number of riders who finished the race was 94,[17] a record high to that point.[18] The average age of riders in the race was 27.5 years,[19] ranging from 21-year-old Tiziano Galvanin (Legnano–Pirelli) to 40-year-old Pino Cerami (Peugeot–BP–Dunlop).[20][21] The Legnano–Pirelli cyclists had the youngest average age while Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro cyclists had the oldest.[19] The presentation of the teams — where the members of each team's roster are introduced in front of the media and local dignitaries — took place outside the Place de la Carrière in Nancy before the start of the opening stage in the city.[22]

The teams entering the race were:[10][9][23]

Majority of French cyclists

Majority of Italian cyclists

Majority of Belgian cyclists

Pre-race favourites

.jpg)

The leading contender for the overall general classification before the Tour was the defending champion Jacques Anquetil of Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson.[24][25][26][27] His closest rivals were thought to be Rik Van Looy (Flandria–Faema–Clément) and Raymond Poulidor (Mercier–BP–Hutchinson).[28][29][30][31] The other riders considered contenders for the general classification were Rudi Altig (Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson), Charly Gaul (Gazzola–Fiorelli–Hutchinson), Federico Bahamontes (Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro), Gastone Nencini (Ignis–Moschettieri), Henry Anglade (Liberia–Grammont–Wolber), Guido Carlesi (Philco), Tom Simpson (Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani), Ercole Baldini (Ignis–Moschettieri) and Hans Junkermann (Wiel's–Groene Leeuw).[32][33][30][34][35][36][37] Of these, three were former winners of the Tour: Gaul (1958), Bahamontes (1959) and Nencini (1960).[38]

Frenchman Anquetil, who also won the Tour in 1957, had dominated the 1961 Tour;[38] he led from the first day to the end, with a winning margin of over twelve minutes.[39][38] At the Vuelta a España (one of the three Grand Tours, along with the Tour de France and the Giro d'Italia) which ended on 13 May,[40] he withdrew from the race before the final stage suffering from viral hepatitis;[41][42] his position in the general classification after the penultimate stage was 32nd.[43] His teammate Altig won the Vuelta and was ahead of his teammate and team leader Anquetil overall until he quit the race,[40][43] so observers expected some internal team struggle in the Tour.[42][44] After recovering for ten days, Anquetil went against his doctor's orders and rode the week-long stage race Critérium du Dauphiné,[45] finishing seventh overall.[46] Anquetil's former bitter rival Raphaël Géminiani was then selected as the head team manager of Saint-Raphaël for the Tour. Unhappy, Anquetil asked his sponsors to replace Géminiani; they declined his request.[47][42]

Winner of the previous two world road race championships, Van Looy, made his Tour debut in 1962.[48][49] He had avoided riding the Tour because he thought he did not have the full support of the Belgium team, but with Flandria he had control over rider selection.[50][51] He had a successful season leading up to the Tour, winning the one-day classics Paris–Roubaix, the Tour of Flanders and Gent–Wevelgem, and two stages of the Giro d'Italia.[48][52] He crashed during training four days before the Tour which caused a muscular stretch in his left thigh.[53] Although Van Looy was known as a one-day classics specialist, he was considered a threat to Anquetil,[54] who himself named Van Looy as the only rider who concerned him, fearing the high number of "flat" stage wins that awarded time bonuses could potentially add up to eight minutes.[55] A "duel" between him and Anquetil was billed by the press.[51][30][34][35]

Poulidor was in his third year as a professional, and was more popular in his home country than his compatriot Anquetil. In 1961, he won the national road race championship and Milan–San Remo classic.[56][42] It was his first appearance in the Tour; he did not ride the 1961 race on the advice of his trade team manager, Antonin Magne, who did not want him riding as a domestique for Anquetil, and undermine his commercial value.[57][58] Anquetil dismissed the media's prediction that Poulidor was his rival, saying: "All Poulidor does is follow. He never takes the initiative."[29] In training in the lead up to the Tour, Poulidor broke his left little finger and began the race with a cast on his forearm.[59][60][29][61]

Route and stages

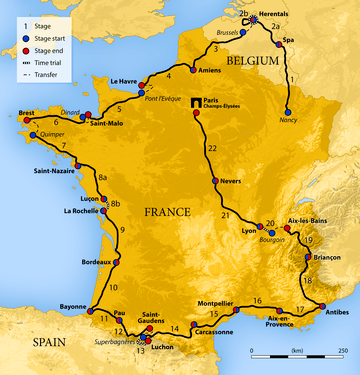

.jpg)

The route for the 1962 edition of the Tour de France was announced on 14 December 1961.[62] Notable features of the route were the absence of rest days and a large amount of time trialling.[63] Speaking of the announcement, Jacques Anquetil said that he did not fear the mountains and that although the time trials favoured him, he would not "complain" if they were not included.[62] Gastone Nencini complained about the number of time trials.[62] Rik Van Looy threatened not to ride, feeling it was too hard, and the time trials did not suit him. He said: "Four times, you are crazy. Why not a normal route? I will not start this Tour. I do not intend to play for three weeks."[63][64]

The opening stage (known as the Grand Départ) started in Nancy, in north-eastern France. The stage ended in the Belgian town of Spa. Belgium hosted stages 2a, and 2b, in Herentals, and the beginning of the third in Brussels. This stage brought the race into northern France with the finish in Amiens. Stage four headed to the coast, westwards to Le Havre, with the following two stages taking the Tour along a coastal route to the western tip of the country. Stages seven to ten formed a continuous journey along the west coast to the foot of the Pyrenees at Bayonne. The Pyrenees hosted the next four stages, with the fourteenth finishing in Carcassonne. Stages fifteen to seventeen took the race to the south-east at Antibes. Stage eighteen headed north into the Alps and its finish in Briançon. The nineteenth stage moved the race out of the mountains and down to Aix-les-Bains. The final three stages took a northerly direction back to the north-east to finish at the Parc des Princes stadium in Paris.[65][66]

There were 22 stages in the race, including two split stages, covering a total distance of 4,274 km (2,656 mi), 123 km (76 mi) shorter than the 1961 Tour.[67] The longest mass-start stage was the 22nd at 271 km (168 mi), and stage 2a was the shortest at 147 km (91 mi).[68] The race featured 49.5 km (31 mi) more time trialling than in the previous Tour, a total of 152.5 km (95 mi); three stages (8b, 13, and 20) were individual time trial events and one (2b) a team time trial.[69][70] There was only one summit finish, in stage 13's time trial to the Superbagnères ski resort.[71] On stage 18, the climb to the summit of the Cime de la Bonette Alpine mountain,[n 3] including the Col de Restefond and Col de la Bonette passes, respectively, was used for the first time in the Tour in 1962.[72] At an altitude of 2,802 metres (9,193 feet), it is one of the highest paved roads in Europe and the highest point of elevation reached in the history of the Tour (as of 2016).[73][74] The Bonette was among six first-category rated climbs in the race.[71] The Tour included four new start or finish locations: Spa, in stages 1 and 2; Herentals, in stages 2a and 2b; Luçon, in stages 8a and 8b; and Nevers, in stages 21 and 22.[70] In 1962, the final 30 km (19 mi) of each stage of the Tour was broadcast live for the first time.[75]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 June | Nancy to Spa (Belgium) | 253 km (157 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2a | 25 June | Spa (Belgium) to Herentals (Belgium) | 147 km (91 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2b | Herentals (Belgium) | 23 km (14 mi) | Team time trial | Faema–Flandria–Clement | ||

| 3 | 26 June | Brussels (Belgium) to Amiens | 210 km (130 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 4 | 27 June | Amiens to Le Havre | 196.5 km (122.1 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5 | 28 June | Pont l'Evêque to Saint-Malo | 215 km (134 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6 | 29 June | Dinard to Brest | 235.5 km (146.3 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 7 | 30 June | Quimper to Saint-Nazaire | 201 km (125 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8a | 1 July | Saint-Nazaire to Luçon | 155 km (96 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8b | Luçon to La Rochelle | 43 km (27 mi) | Individual time trial | |||

| 9 | 2 July | La Rochelle to Bordeaux | 214 km (133 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 10 | 3 July | Bordeaux to Bayonne | 184.5 km (114.6 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 11 | 4 July | Bayonne to Pau | 155.5 km (96.6 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 12 | 5 July | Pau to Saint-Gaudens | 207.5 km (128.9 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 13 | 6 July | Luchon to Superbagnères | 18.5 km (11.5 mi) | Mountain time trial | ||

| 14 | 7 July | Luchon to Carcassonne | 215 km (134 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 15 | 8 July | Carcassonne to Montpellier | 196.5 km (122.1 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 16 | 9 July | Montpellier to Aix-en-Provence | 185 km (115 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 17 | 10 July | Aix-en-Provence to Antibes | 201 km (125 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 18 | 11 July | Antibes to Briançon | 241.5 km (150.1 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 19 | 12 July | Briançon to Aix-les-Bains | 204.5 km (127.1 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 20 | 13 July | Bourgoin to Lyon | 68 km (42 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 21 | 14 July | Lyon to Nevers | 232 km (144 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 22 | 15 July | Nevers to Paris | 271 km (168 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| Total | 4,274 km (2,656 mi)[67] | |||||

Race overview

In the opening stage, a 23-man breakaway group of riders escaped the peloton (main group) as it passed Luxembourg City with 145 km (90 mi) remaining. It stayed away and came to the finish over six minutes ahead, with Rudi Altig winning the sprint, and taking the first yellow jersey as leader of the general classification. Rik Van Looy, third on the stage, was denied the opportunity to wear the yellow jersey in his own country and into his home town of Herentals at the end of the following stage. Pre-race favourites Raymond Poulidor, Charly Gaul and Federico Bahamontes were not present in the lead group. Altig also took the points classification's green jersey, and Jean Selic (Liberia–Grammont–Wolber) led the mountains classification.[22][77][78] The first half of the second stage ended with a bunch sprint won by André Darrigade of Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani. Van Looy escaped close to the end but took a wrong turn; he placed fourth. Darrigade, second previously, took the yellow and green jerseys, with Angelino Soler taking the lead of the mountains classification. The team time trial that took place in Herentals later in the day was won by Flandria–Faema–Clément; their winning margin over second-place Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani was 1 min 15 s, and moved four of their riders into the top ten.[79] Altig retook the yellow jersey in stage three's sprint from a breakaway consisting of 41 riders. Gaul and Bahamontes lost further time, finishing in the peloton over five minutes down.[80]

In the fourth stage, Mercier–BP–Hutchinson's Willy Vanden Berghen won the sprint finish between a group of six that went clear with around 100 km (62 mi) to go. Altig reclaimed the green jersey.[81] Stage five ended in a bunch sprint won by Emile Daems (Philco), with Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani's Rolf Wolfshohl taking the lead of the mountains classification.[82] In the sixth stage, a 16-man (15 at the end) group escaped 23 km (14 mi) in and held on to the finish at Brest, with Robert Cazala of Mercier–BP–Hutchinson winning the sprint. Altig and Anquetil were not there, but they had sent their teammate Albertus Geldermans to protect the team's interests. Geldermans was the best-placed man in the break, and their finishing margin of over five minutes was so large that Geldermans became the new overall leader.[33][83] Huub Zilverberg (Flandria–Faema–Clément) won stage seven from a two-way sprint with Bas Maliepaard (Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani); the pair distanced a breakaway of twenty riders in the final 2 km (1 mi) and finished five seconds ahead at the finish in Saint-Nazaire.[37][84] As the chasing breakaway went through a narrow section of the finishing straight, Gastone Nencini hit a gendarme (French police officer) and fell, also bringing down Darrigade. Like much of the first week, the average speed of the stage was unusually high, calculated to be 44.87 km/h (27.88 mph), the fastest recorded stage to that point above a distance of 200 km (124 mi).[37]

.jpg)

In the first part of the eighth stage, another large group escaped, which in the final kilometers had merged with a further chasing breakaway and ended with a sprint victory for Mario Minieri of Ghigi in Luçon's velodrome. Breakaway rider Darrigade became the new general classification leader, his second stint in yellow. The flat 43 km (27 mi) individual time trial from Luçon to La Rochelle in the second part of the stage was won by Anquetil, with Ercole Baldini second, 22 seconds down.[37][84] Because of a successful breakaway in stage nine, Darrigade lost the lead to Flandria–Faema–Clément rider Willy Schroeders; Antonio Bailetti (Carpano) won the stage.[37] Willy Vannitsen (Wiel's–Groene Leeuw) won the tenth stage's bunch sprint.[85] In stage eleven, a crash 35 km (22 mi) in involving 22 riders was caused by a motorbike carrying a photographer. Van Looy, whose back was injured by the motorbike's handlebars, was the most notable casualty; he was able to continue for a further 30 km (19 mi), before he was advised to retire from the race by the Tour's doctor, Pierre Dumas.[86][87][88][89] The stage was won by Eddy Pauwels (Wiel's–Groene Leeuw), who dropped his fellow breakaway riders and soloed to victory with a four-minute advantage at Pau's motor race street circuit.[88][89]

Stage twelve, the first mountain stage in the Pyrenees, saw Cazala take his second win from a sprint between an elite group of climbers and overall favourites that finished together after the descent to Saint-Gaudens.[71][90] Schroeders could not keep up with the aforementioned riders, and lost the lead to Tom Simpson, who was in the group;[90] the British rider became the first non-mainland European to wear the yellow jersey.[91] Bahamontes led over the first-category Col du Tourmalet, and the two other lower categorised climbs, to take the lead in the mountains classification.[90] The next stage, an 18.5 km (11 mi) mountain time trial, was won by Bahamontes. Simpson lost the lead to Jef Planckaert of Flandria–Faema–Clément, who finished in second place.[92] The final Pyrenean stage, the fourteenth, saw Jean Stablinski (Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson) attack his 10-strong breakaway with 25 km (16 mi) remaining and solo to the finish in Carcassonne with a margin of twelve seconds.[93] The first of the three transitional stages, fifteen, that crossed France's southern coastline ended in a bunch sprint won by Vannitsen.[94] In stage sixteen, Daems and Bailetti escaped the peloton with 60 km (37 mi) to go, with Daems attacking to win with a margin of three minutes;[95] the chasing group of seven came in eight minutes later.[96] Altig won the seventeenth stage in a sprint from a four-rider breakaway that finished over six minutes ahead of the peloton.[97]

In the first of the two Alpine stages, the eighteenth, attacks were expected. Instead, the riders went at a slow pace; in the first four hours, they had only raced 100 km (62 mi). Later, some attacks took place, but they failed for punctured tires and the defending tactics of the leading riders. So in the end, Daems, who was a sprinter and not a climber, was able to win this mountain stage.[98] The 19th stage followed the same route as the 21st stage of the 1958 Tour, where Gaul had won the race.[99] Poulidor's injured hand was better now, and his team manager told him that it was time to attack. Poulidor was placed ninth in the general classification, ten minutes in arrears, so he would have not likely been seen as a threat.[99] Poulidor attacked over the final climbs and soloed to the finish at Aix-les-Bains with an advantage of over three minutes over his rivals,[99][100] moving him to the third place overall, with Planckaert still leading and Anquetil second.[101] In the individual time trial in stage twenty, Planckaert lost over five minutes to the winner, Anquetil, who took the overall lead.[102] Stage 21 ended in a bunch sprint won by Dino Bruni of Gazzola–Fiorelli–Hutchinson.[103]

In the final stage, Benedetti gained his second victory of the race from a sprint bunch in front of an estimated crowd of 30,000 at Parc des Princes.[104] Anquetil finished the race to claim his third Tour de France, equalling the record number of Tour wins by a rider with Belgian Philippe Thys and Frenchman Louison Bobet.[105] It was revealed later that Anquetil had ridden the race with tapeworm.[106] He beat second-placed Planckaert by 4 min 59 s, with Poulidor third, a further 5 min 25 s down. Altig won the points classification with a total of 173, 29 ahead of Daems in second. Bahamontes won the mountains classification with 137 points, 60 ahead of second-placed Imerio Massignan (Legnano–Pirelli).[107] Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson won the team classification, which they led from the opening stage, with Mercier–BP–Hutchinson coming second and Flandria–Faema–Clément third.[107] The riders with the most stages wins were Altig and Daems, with three each.[76]

Doping

During the night after the thirteenth stage, pre-race outsider Hans Junkermann became ill. He was placed seventh in the general classification, and the following day, stage fourteen, his team requested the start be delayed, which the organisation allowed. He was dropped by the peloton on the first climb 50 km (31 mi) in, and abandoned the race, saying "bad fish" was the cause.[108] Fourteen riders withdrew from the Tour that day, all blaming food poisoning from rotten fish at the same hotel,[109][110][111] including the former general classification leader Willy Schroeder and another pre-race contender Gastone Nencini.[102] Writing in the French sports newspaper L'Équipe, the Tour's race director, Jacques Goddet, said he did not believe their excuse and believed they had doped to recover time lost in the previous stage's time trial.[112] Nothing was proven, although the hotel said they did not serve fish that night.[108] A communiqué released by the Pierre Dumas warned that if riders and their soigneurs did not stop "certain forms of preparation," there would be daily post-stage hotel room inspections.[110][113][114] Upset by this and doping accusations in the press, the riders threatened a fifteen-minute strike, but the journalist Jean Bobet, a former cyclist, was able to talk them into continuing,[111][108][110] although he provided the commentary for the documentary film about the 1962 Tour, Vive le Tour by Louis Malle,[115] which ridiculed the riders and their 'bad fish' explanation.[116] In the following days, Dumas began to organise the inaugural European Conference on Doping and the Biological Preparation of the Competitive Athlete, which took place in January 1963.[110] Due to the largest amount of riders involved coming from Wiel's–Groene Leeuw, with four,[102] the scandal is referred to as the "Wiel's affair".[108][117]

Classification leadership

There were three main individual classifications contested in the 1962 Tour de France, as well as a team competition. Two of them awarded jerseys to their leaders.[118] The most important was the general classification, which was calculated by adding each rider's finishing times on each stage.[119] Time bonuses were awarded to the top two positions at the end of every stage, including the individual time trials, but not the team time trial; first place received 1 minute and second place got 30 seconds.[120][102] The rider with the lowest cumulative time was the winner of the general classification and was considered the overall winner of the Tour.[121] The rider leading the classification wore a yellow jersey.[118]

The second classification was the points classification. Riders were awarded points for finishing in the top fifteen places on each stage. The first rider at each stage finish was awarded 25 points, the second 20 points, the third 16 points, the fourth 14 points, the fifth 12 points, the sixth 10 points, down to 1 point for the rider in fifteenth.[122] The classification leader was identified by a green jersey.[118]

| Category | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (6 mountains) | 15 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Second (5 mountains) | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Third (5 mountains) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Fourth (18 mountains) | 3 | 2 | 1 |

The third classification was the mountains classification. Most stages of the race included one or more categorised climbs, in which points were awarded to the riders who reached the summit first.[123] The climbs were categorised as fourth-, third-, second- or first-category, with the more difficult climbs rated lower.[65] The calculation for the mountains classification was changed in 1962, and the fourth category was added.[70][11] The leader of the classification was not identified by a jersey.[118]

The final classification was a team classification. This was calculated by adding together the times of the first three cyclists of a team on each stage; the team with the lowest time on a stage won one point. The overall team classification was calculated by counting the number of points across all the stages, with second and third lowest combined times determining placings.[124][125] The spilt stages (two and eight) were each combined.[125] The riders on the team who led this classification were identified with yellow casquettes (English: caps).[126]

In addition, there was a combativity award given after each stage to the most aggressive rider;[122][n 4] the decision was made by a jury composed of journalists.[128] The split stages each had a combined winner.[128][129][130] At the conclusion of the Tour, Eddy Pauwels won the overall super-combativity award, also decided by journalists.[128][131]

A total of 583,425 French new francs (NF) was awarded in cash prizes in the race, with the overall winner of the general classification receiving 20,000 NF.[68] The points and mountains classification winners got 10,000 NF and 5,000 NF respectively. The team classification winners were given 30,000 NF. The winner of the super-combativity award winner was given 6,000 NF and a Renault R8 car.[122] There was also a special award with a prize of 3,000 NF, the Souvenir Henri Desgrange, given to the first rider (Juan Campillo of Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro) to pass the summit of the 2,058 m (6,752 ft)-high Col du Lautaret on stage nineteen.[132][133]

Final standings

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | 114h 31' 54" | |

| 2 | Flandria–Faema–Clément | + 4' 59" | |

| 3 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 10' 24" | |

| 4 | Carpano | + 13' 01" | |

| 5 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | + 14' 05" | |

| 6 | Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani | + 17' 09" | |

| 7 | Legnano–Pirelli | + 17' 50" | |

| 8 | Ignis–Moschettieri | + 19' 00" | |

| 9 | Gazzola–Fiorelli–Hutchinson | + 19' 11" | |

| 10 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 23' 04" |

Points classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | 173 | |

| 2 | Philco | 144 | |

| 3 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | 140 | |

| 4 | Ignis–Moschettieri | 135 | |

| 5 | Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani | 131 | |

| 6 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | 99 | |

| 7 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 83 | |

| 8 | Flandria–Faema–Clément | 77 | |

| 9 | Flandria–Faema–Clément | 76 | |

| 10 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 73 |

Mountains classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro | 137 | |

| 2 | Legnano–Pirelli | 77 | |

| 3 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 70 | |

| 4 | Gazzola–Fiorelli–Hutchinson | 58 | |

| 5 | Flandria–Faema–Clément | 37 | |

| 6 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 35 | |

| 7 | Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani | 33 | |

| 8 | Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro | 32 | |

| 9 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | 31 | |

| 10 | Philco | 18 |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Wins | 2nds | 3rds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saint-Raphaël–Helyett–Hutchinson | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | Flandria–Faema–Clément | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 6 | Philco | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | Ignis–Moschettieri | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | Gazzola–Fiorelli–Hutchinson | 1 | — | 1 |

| 9 | Margnat–Paloma–D'Alessandro | 1 | — | — |

| 10 | Carpano | — | 2 | 3 |

Super-combativity award

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 313 | |

| 2 | Liberia–Grammont–Wolber | 137 | |

| 3 | Gitane–Leroux–Dunlop–R. Geminiani | 133 | |

| 4 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 112 | |

| 5 | Flandria–Faema–Clément | 35 |

See also

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ↑ The Tour's director, founder of the race Henri Desgrange, who had always wanted the race to be won on individual strength, changed it to the national format after he believed the teams from Belgium had helped Alcyon–Dunlop rider Maurice De Waele win the 1929 race, although he was unwell.[2]

- ↑ The leader of the Legnano–Pirelli team, Graziano Battistini, was listed on the start list,[10] but he withdrew from the Tour before stage one and was not replaced. Although he was cleared to race by the Tour's doctor, Pierre Dumas, Battistini thought he was suffering from azotemia.[14] His team manager, Eberardo Pavesi, allowed him to make his own decision.[15]

- ↑ In the given sources from 1962, the Cime de la Bonette climb in stage 18 is referred to as the Col de Restefond.[65][66][71]

- ↑ In the 2017 Tour de France, the combativity award winner was officially described as the rider who the "made the greatest effort and who demonstrated the best qualities of sportsmanship".[127]

References

- ↑ Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 218.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 253–259.

- ↑ Dauncey 2012, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Reed 2015, p. 66.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2006, p. 5.

- ↑ Hanold 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ "Niet minder dan 22 ploegen" [No less than 22 teams]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 2 February 1962. p. 11. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "De organisatoren van de Tour" [The organisers of the Tour]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 24 February 1962. p. 15. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1962 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "La lista de los 150 participantes" [The list of the 150 participants] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 24 June 1962. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- 1 2 "Los datos funamentales del 48 "Tour"" [The fundamental data of the 48th "Tour"] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 24 June 1961. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ Nelsson 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ R. Torres (6 October 1961). "El Tour 1962 se disputará por equipos de nueve o diez corredores de marcas comerciales" [The 1962 Tour will be contested by trade teams of nine or ten riders] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Varale, Vittorio (25 June 1962). "Battistini deciso a non correre il Tour malgrado il parere favorevole del medico" [Battistini decides not to run the Tour despite the doctor's favourable opinion]. La Stampa (in Italian). p. 11. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ↑ Pignata, Gianna (25 June 1962). "La Leganano nei pasticci Graziano Battistini "maiala immaginarie"?". La Stampa (in Italian). p. 7. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ↑ "Debutants". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- 1 2 "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1962 – Stage 22 Nevers > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ Clifford 1965, p. 168.

- 1 2 "Average age". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ↑ "Youngest riders". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ↑ "Oldest riders". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- 1 2 "Rudi Altig won eerste etappe Tour de France" [Rudi Altig won the first stage Tour de France]. De Waarheid (in Dutch). 25 June 1962. p. 4. Retrieved 21 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "De 15 ploegen" [The 15 teams]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 25 June 1962. p. 5. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ Bauer 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ McKay 2014, p. 334.

- ↑ Woodland 2007, p. 105.

- ↑ Pignata, Gianna (22 June 1962). "Prende ill via da Nancy un «Tour» massacrante". La Stampa (in Italian). Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ Howard 2008, pp. 156–157.

- 1 2 3 Yates 2001, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 "Kandidaten" [Candidates]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 20 June 1962. p. 11. Retrieved 23 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Bij nieuwe formule van fabrieksploegen Rik van Looy en Jacques Anquetil grootste kanshebbers in de Tour" [With new formula of factory teams Rik van Looy and Jacques Anquetil biggest contenders in the Tour]. Friese Koerier (in Dutch). ANP. 22 June 1962. Retrieved 24 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2012, p. 207.

- 1 2 McGann & McGann 2006, p. 255.

- 1 2 de Deugd, Rinus (20 June 1962). "Duel Anquetil-Van Looy kan interessant zijn" [Anquetil-Van Looy duel may be interesting]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 "Nederlands als paladinen in de Tour de France". De Tijd-Maasbode (in Dutch). 22 June 1962. p. 7. Retrieved 24 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ Schilperoort, B. M. (22 June 1962). "Tout du Tour". Algemeen Handelsblad (in Dutch). p. 13. Retrieved 30 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wadley, Jock (September 1962). "Early pattern from Aimens to Bordeux". Coureur Sporting Cyclist. Vol. 6 no. 9. London: Charles Buchan's Publications. pp. 15–19.

- 1 2 3 Augendre 2016, p. 112.

- ↑ Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 190.

- 1 2 "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 14 May 1962. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Howard 2008, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 4 McGann & McGann 2006, p. 254.

- 1 2 "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 13 May 1962. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "Altig capitano n. 2" [Altig captain no. 2]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 22 June 1962. p. 8. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Yates 2001, p. 112.

- ↑ Howard 2008, p. 154.

- ↑ Howard 2008, pp. 154–155.

- 1 2 Woodland 2007, pp. 390–391.

- ↑ Yates 2001, p. 114.

- ↑ Clifford 1965, p. 165.

- 1 2 Liber, Jan (22 June 1962). "Tour der merken" [Tour of the brands]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). p. 25. Retrieved 24 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Rik Van Looy – 1962 season". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Pignata, Gianna (21 June 1962). "Van Looy cade in allenamento alla vigila del Giro di Francia". La Stampa (in Italian). Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- 1 2 Howard 2008, p. 156.

- ↑ Wadley, Jock (September 1962). "Yes, Jacques, you were all right". Coureur Sporting Cyclist. Vol. 6 no. 9. London: Charles Buchan's Publications. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Howard 2008, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Howard 2008, p. 157.

- ↑ Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 112.

- ↑ Armstrong 1971, p. 16.

- ↑ Nicholson 2016, p. 179.

- ↑ Wadley, Jock (September 1962). "Col de Restford, the new giant of the Alps". Coureur Sporting Cyclist. Vol. 6 no. 9. London: Charles Buchan's Publications. pp. 26–28.

- 1 2 3 "Il tracciato del Tour criticato da Van Looy, Nencini e Defilippis" [The route of the Tour criticized by Van Looy, Nencini and Defilippis]. La Stampa (in Italian). 15 December 1961. p. 8.

- 1 2 "Tour de France 1962 zonder rustdag en met vier tijdritten" [Tour de France 1962 without rest day and with four time trials]. De Tijd (in Dutch). 15 December 1961. p. 7. Retrieved 3 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Van Looy blijft thuis "Nederland niet in de Tour" zegt Sehulte" [Van Looy stays home "The Netherlands is not in the Tour" says Sehulte]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 15 December 1961. p. 17. Retrieved 3 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 3 4 "Veel is anders" [Much is different]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 22 June 1962. p. 25. Retrieved 25 April 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 3 "Las 22 etapas del "Tour"" [The 22 stages of the "Tour"] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 24 June 1962. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- 1 2 Augendre 2016, p. 109.

- 1 2 Augendre 2016, p. 53.

- ↑ "48ème Tour de France 1961" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "49ème Tour de France 1962" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ecco il Tour" [Here is the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 23 June 1962. p. 3. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ Cossins 2013, p. 125.

- ↑ Geser 2013, p. 230.

- ↑ Bacon, Ellis (15 March 2016). "Col de la Bonette". Cyclist. Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 247.

- 1 2 "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1962 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 25 June 1962. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Tour de France". Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 26 June 1962. p. 5. Retrieved 27 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 27 June 1962. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ "Nederlanders doen het goed in de Tour" [Dutch are doing well in the Tour]. De Waarheid. 28 June 1962. p. 6. Retrieved 28 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Tour de France". Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 29 June 1962. p. 5. Retrieved 28 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Geldermans de gele trui!" [Geldermans the yellow jersey!]. De Waarheid (in Dutch). 30 June 1962. p. 8. Retrieved 29 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 "Tour de France". Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 2 July 1962. p. 3. Retrieved 31 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Ronde van Frankrijk maakte wandeletappe" [Tour of France made walking paths]. De Waarheid (in Dutch). 4 July 1962. p. 4. Retrieved 31 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Zege Pauwels schrale troost voor Belgen" [Zege Pauwels had a slight consolation for Belgians]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 5 July 1962. p. 13. Retrieved 31 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ Clifford 1965, p. 167.

- 1 2 "Etappe Bayonne-Pau niet veel om het lijf" [Bayonne-Pau stage not much about the body]. De Waarheid (in Dutch). 5 July 1962. p. 6. Retrieved 31 May 2017 – via Delpher.

- 1 2 Wadley, Jock (September 1962). ""I'll be back again" – Van Looy". Coureur Sporting Cyclist. Vol. 6 no. 9. London: Charles Buchan's Publications. pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 3 "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 6 July 1962. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ Wilcockson 2007, p. 84.

- ↑ "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 7 July 1962. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Planckaert behoudt de gele trui" [Planckaert maintains the yellow jersey]. De Waarheid (in Dutch). 9 June 1962. p. 5. Retrieved 2 June 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 9 July 1962. p. 9. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ "Belg Daems won Tour-rit" [Belg Daems won a Tour ride]. De Waarheid (in Dutch). 10 July 1962. p. 4. Retrieved 3 June 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Tour in cijfers" [Tour in numbers]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 10 July 1962. p. 7. Retrieved 3 June 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 11 July 1962. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2006, p. 257–258.

- 1 2 3 McGann & McGann 2006, p. 258.

- ↑ Fife, Graeme (15 April 2013). "Tour de France 1962". Rapha. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 13 July 1962. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 14 July 1962. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 15 July 1962. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Anquetil onbedreigd eerste in Parijs" [Anquetil unbeaten first in Paris]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 16 July 1962. p. 9. Retrieved 13 June 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ Augendre 2016, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Yates 2001, p. 115.

- 1 2 3 4 "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 16 July 1962. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 McGann & McGann 2006, p. 257.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2012, p. 117.

- 1 2 3 4 Thompson 2008, p. 231.

- 1 2 "Fishy story from Luchon". Coureur Sporting Cyclist. Vol. 6 no. 9. London: Charles Buchan's Publications. September 1962. p. 25.

- ↑ McKay 2014, p. 336.

- ↑ Johnson 2016, chpt. 11.

- ↑ Nelsson 2012, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ "Louis Malle celebrates the Tour". Louison Bobet. 12 June 2015. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ Louis Malle (Director) (October 1962). Vive le Tour [Long live the Tour] (Motion picture) (in French). Event occurs at 10 min 45 s in.

- ↑ Woodland 2007, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 Cunningham, Josh (4 July 2016). "History of the Tour de France jerseys". Cyclist. Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ Liggett, Raia & Lewis 2005, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 26 June 1962. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ Liggett, Raia & Lewis 2005, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 4 "Er liggen miljoenen te rapen" [There are millions to be picked up]. Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 22 June 1962. p. 16. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017.

- ↑ Liggett, Raia & Lewis 2005, pp. 35–37.

- 1 2 "Tour de France final result". Coureur Sporting Cyclist. Vol. 6 no. 9. London: Charles Buchan's Publications. September 1962. p. 37.

- 1 2 "Goddet verwacht een spannende Tour". De Waarheid (in Dutch). 9 June 1962. p. 10. Retrieved 24 April 2017 – via Delpher.

- ↑ Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- ↑ Race regulations 2017, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 "Strijdlust" [Combativity award]. Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 16 July 1962. p. 12. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "La course au sommet est commencée" [The race to the summit has begun] (PDF). Feuille d'Avis du Valais (in French). 26 June 1962. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "Strijdlust" [Combativity award]. Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 2 July 1962. p. 11. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tutte le cifre del Tour" [All the figures of the Tour]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 16 July 1962. p. 8. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ Woodland 2007, p. 156.

- ↑ "Kleine misrekening" [Small miscalculation]. Friese Koerier (in Dutch). 13 July 1962. p. 13. Retrieved 24 April 2017 – via Delpher.

Sources

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Armstrong, David (1971). Eternal Second. Yorkshire, UK: Kennedy Brothers.

- Bauer, Kristian (2011). Ride a Stage of the Tour de France: The Legendary Climbs and How to Ride Them. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4081-3333-0.

- Dauncey, Hugh; Hare, Geoff (2003). The Tour De France, 1903–2003: A Century of Sporting Structures, Meanings and Values. London: Frank Cass & Co. ISBN 978-0-203-50241-9.

- Dauncey, Hugh (2012). French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History. Contemporary French and Francophone Cultures. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-835-1.

- Clifford, Peter (1965). The Tour de France. London: Stanley Paul.

- Cossins, Peter (2013). Le Tour 100: The definitive history of the world's greatest race. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 978-1-84403-759-9.

- Fotheringham, Alasdair (2012). The Eagle of Toledo: The Life and Times of Federico Bahamontes. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-700-7.

- Geser, Rudolf (2013). Alpine Passes by Road Bike: 100 Routes Through the Alps and how to Ride Them. London: A & C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-7995-6.

- Hanold, Maylon (2012). World Sports: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-779-6.

- Howard, Paul (2008). Sex, Lies and Handlebar Tape: The Remarkable Life of Jacques Anquetil, the First Five-Times Winner of the Tour de France. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84596-301-9.

- Johnson, Mark (2016). Spitting in the Soup: Inside the Dirty Game of Doping in Sports. Boulder, CO: VeloPress. ISBN 978-1-937716-82-0.

- Liggett, Phil; Raia, James; Lewis, Sammarye (2005). Tour de France for Dummies. For Dummies. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7645-8449-7.

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France, Volume 1: 1903–1964. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.

- McKay, Feargal (2014). The Complete Book of the Tour de France. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-78131-265-0.

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.

- Nelsson, Richard (2012). The Tour de France ... to the Bitter End. London: Guardian Books. ISBN 978-0-85265-336-4.

- Nicholson, Geoffrey (2016). The Great Bike Race. Oxford, UK: Velodrome Publishing. ISBN 978-1-911162-10-0.

- Race regulations (PDF). Tour de France. Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017. }

- Reed, Eric (2015). Selling the Yellow Jersey: The Tour de France in the Global Era. Oakland, CA: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-20667-7.

- Thompson, Christopher S. (2008). The Tour de France. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93486-3.

- Wilcockson, John (2007). The 2007 Tour de France. Boulder, CO: VeloPress. ISBN 978-1-934030-10-3.

- Woodland, Les (2007) [1st. pub. 2003]. The Yellow Jersey Companion to the Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-224-08016-3.

- Yates, Richard (2001). Master Jacques: The Enigma of Jacques Anquetil. Norwich, UK: Mousehold Press. ISBN 978-1-874739-18-0.

External links

![]()

.jpg)

.jpg)