Second Bill of Rights

The Second Bill of Rights is a list of rights that was proposed by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt during his State of the Union Address on Tuesday, January 11, 1944.[1] In his address, Roosevelt suggested that the nation had come to recognize and should now implement, a second "bill of rights". Roosevelt's argument was that the "political rights" guaranteed by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights had "proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness". His remedy was to declare an "economic bill of rights" to guarantee these specific rights:

- Employment (right to work[notes 1]), food, clothing and leisure with enough income to support them

- Farmers' rights to a fair income

- Freedom from unfair competition and monopolies

- Housing

- Medical care

- Social security

- Education

Roosevelt stated that having such rights would guarantee American security and that the United States' place in the world depended upon how far the rights had been carried into practice.

Background

In the runup to the Second World War, the United States had suffered through the Great Depression following the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Roosevelt's election at the end of 1932 was based on a commitment to reform the economy and society through a "New Deal" program. The first indication of a commitment to government guarantees of social and economic rights came in an address to the Commonwealth Club on September 23, 1932 during his campaign. The speech was written with Adolf A. Berle, a professor of corporate law at Columbia University. A key passage read:

As I see it, the task of government in its relation to business is to assist the development of an economic declaration of rights, an economic constitutional order. This is the common task of statesman and business man. It is the minimum requirement of a more permanently safe order of things.

Throughout Roosevelt's presidency, he returned to the same theme continually over the course of the New Deal. Also in the Atlantic Charter, an international commitment was made as the Allies thought about how to "win the peace" following victory in the Second World War.

Roosevelt's speech

During Roosevelt's January 11, 1944 message to the Congress on the State of the Union, he said the following:[2]

It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.

This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights—among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty.

As our nation has grown in size and stature, however—as our industrial economy expanded—these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.

We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. "Necessitous men are not free men."[3] People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all—regardless of station, race, or creed.

Among these are:

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

America's own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for all our citizens. For unless there is security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world.

Significance

Roosevelt saw the economic Bill of Rights as something that would at least initially be implemented by legislation, but that did not exclude either the Supreme Court's development of constitutional jurisprudence or amendments to the Constitution. Roosevelt's model assumed that federal government would take the lead, but that did not prevent states improving their own legislative or constitutional framework beyond the federal minimum. Much of the groundwork had been laid before and during the New Deal, but left many of the Second Bill of Rights' aspirations incomplete. Internationally, the same economic and social rights were written into the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

In federal legislation, the key planks for the right to a useful and remunerative job included the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. After the war was the Employment Act of 1946, which created an objective for the government to eliminate unemployment; and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited unjustified discrimination in the workplace and in access to public and private services. They remained some of the key elements of labor law. The rights to food and fair agricultural wages was assured by numerous Acts on agriculture in the United States and by the Food Stamp Act of 1964. The right to freedom from unfair competition was primarily seen to be achievable through the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice's enforcement of both the Sherman Act of 1890 and the Clayton Act of 1914, with some minor later amendments. The most significant program of change occurred through Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society. The right to housing was developed through a policy of subsidies and government building under the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965. The right to health care was partly improved by the Social Security Act of 1965 and more recently the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The Social Security Act of 1935 had laid the groundwork for protection from fear of old age, sickness, accident and unemployment. The right to a decent education was shaped heavily by Supreme Court jurisprudence and the administration of education was left to the states, particularly with Brown v. Board of Education. A legislative framework developed through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 and in higher education a measure of improvement began with federal assistance and regulation in the Higher Education Act of 1965.

Later in the 1970s, Czech jurist Karel Vasak would categorize these as the "second generation" rights in his theory of three generations of human rights.

Found footage

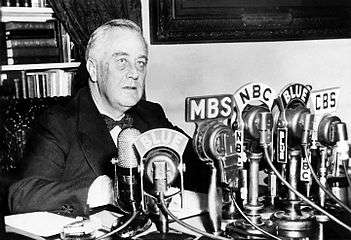

Roosevelt presented the January 11, 1944 State of the Union address to the public on radio as a fireside chat from the White House:

Today I sent my Annual Message to the Congress, as required by the Constitution. It has been my custom to deliver these Annual Messages in person, and they have been broadcast to the Nation. I intended to follow this same custom this year. But like a great many other people, I have had the "flu", and although I am practically recovered, my doctor simply would not let me leave the White House to go up to the Capitol. Only a few of the newspapers of the United States can print the Message in full, and I am anxious that the American people be given an opportunity to hear what I have recommended to the Congress for this very fateful year in our history — and the reasons for those recommendations. Here is what I said …[4]

He asked that newsreel cameras film the last portion of the address, concerning the Second Bill of Rights. This footage was believed lost until it was uncovered in 2008 in South Carolina by Michael Moore while researching the film Capitalism: A Love Story.[5] The footage shows Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights address in its entirety as well as a shot of the eight rights printed on a sheet of paper.[6][7]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bill of Rights

- Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963)

- Economic democracy

- Four Freedoms, enunciated in Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union Address

- Full employment

- Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970)

- Progressive Utilization Theory

- Public education

- Public Service law of the United States

- Social Security

- Universal health care

- Vernon v Bethell

Footnotes

- ↑ This "right to work" is not to be confused with the "right-to-work laws" to which this term usually aludes inside the United States.

Citations

- ↑ "The Economic Bill of Rights". Franklin D. Roosevelt American Heritage Center. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ "State of the Union Message to Congress". Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

- ↑ This phrase is found in the old English property law case, Vernon v Bethell (1762) 28 ER 838, according to Lord Henley LC

- 1 2 Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 28: On the State of the Union (January 11, 1944)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- ↑ "The Best Scenes From Michael Moore's New Movie". The Daily Beast. Sep 22, 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ Capitalism: A Love Story on IMDb (starting approximately at time code 1:55:00)

- ↑ Moore, Michael; et al. (2010). Capitalism: A Love Story (DVD). Traverse City, MI: Front Street Productions, LLC. OCLC 443524847. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

References

- AA Berle, 'Property, Production and Revolution' (1965) 65 Columbia Law Review 1

- CR Sunstein, The Second Bill of Rights: FDR's Unfinished Revolution--And Why We Need It More Than Ever (2004)

External links

- Audio recording of the speech on Youtube

- FDR's Unfinished "Second Bill of Rights" – and Why We Need it Now

| Preceded by 1943 State of the Union Address |

Second Bill of Rights 1944 |

Succeeded by 1945 State of the Union Address |