1877 St. Louis general strike

| 1877 St. Louis general strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 | |||

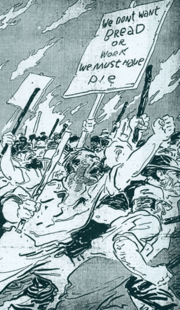

A contemporary newspaper's rendering of the strikers | |||

| Date | July 22–July 28, 1877 | ||

| Location | St. Louis | ||

| Goals | eight-hour day, ban on child labor | ||

| Methods | general strike, rally, lockdowns (rails, industry) | ||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

The 1877 St. Louis general strike is largely accepted as the first general strike in the United States. It grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party, the main radical political party of the era. When the railroad strike reached East St. Louis, Illinois in July 1877, the St. Louis Workingman's Party led a group of approximately 500 people across the river in an act of solidarity with the nearly 1,000 workers on strike.[1] The party transformed, through speeches and organization, an initial strike among railroad workers into a strike by thousands of workers in several industries for the eight-hour day and a ban on child labor. One speaker was noted to say,

All you have to do, gentlemen, for you have the numbers, is to unite on one idea - that workingmen shall rule the country. What man makes, belongs to him, and the workingmen made this country.[1]

At another large rally a black man spoke for those who worked on the steamboats and levees. He asked, "Will you stand to us regardless of color?" The crowd shouted back, "We will!"[1]

The St. Louis strike was marked by a bloodless, efficient and quick take-over by dissatisfied workers of commerce and transportation in the area. By July 22, the St. Louis Commune began to take shape as representatives from almost all the railroad lines met in East St. Louis. They soon elected an executive committee to command the strike and issued General Order No. 1, halting all railroad traffic other than passenger and mail trains. John Bowman, the mayor of East St. Louis, was appointed arbitrator of the committee. He helped the committee select special police to guard the property of the railroads from damage.

The strike reached the business sector by closing packing industry houses surrounding the National Stockyards. At one plant workers allowed processing of 125 cattle in return for 500 cans of beef for the workers. The strike continued to gain momentum, with coopers, newsboys, gasworkers, boatmen, bakers, engineers, cabinetmakers, cigarmakers, brewery workers, millers, and workers of various factory jobs all joining the general strike.[1] Though the East St. Louis strike continued in an orderly fashion, across the river there were isolated incidents of violence with one speaker stating, "The workingmen intend now to assert their rights, even if the result is the shedding of blood.... They are ready to take up arms at any moment."[1]

The strike was ended when some 3,000 federal troops and 5,000 deputized special police killed at least eighteen people in skirmishes around the city. On July 28, 1877, they took control of the Relay Depot, the Commune's command center, and arrested some seventy strikers.[1] With the leadership imprisoned, the strikers surrendered, the wage cuts remained, and 131 strike leaders were fired by the Burlington Railroad.[2]

The Long Depression and the Great Strikes

| 1850s–1873 | 1873–1890 | 1890–1913 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.1 |

| United Kingdom | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| United States | 6.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 |

| France | 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| Italy | 0.9 | 3.0 | |

| Sweden | 3.1 | 3.5 |

The Long Depression, sparked in the United States by the Panic of 1873, had extensive implications for US industry, closing more than a hundred railroads in the first year and cutting construction of new rail lines from 7,500 miles (12,100 km) of track in 1872 to 1,600 miles (2,600 km) in 1875.[4] Approximately 18,000 businesses failed between 1873 and 1875, production in iron and steel dropped as much as 45 percent, and a million or more lost their jobs.[5][6] In 1876, 76 railroad companies went bankrupt or entered receivership in the US alone, and the economic impacts rippled throughout many economic sectors throughout the industrialized world.[7]:31

In mid-1877, tensions erupted in stoppages and civil unrest across the nation in what would become known as the Great Railroad Strike or the Great Strikes. Violence began in Martinsburg, West Virginia and spread along the rail lines through Baltimore and on to several major cities and transportation hubs of the time, including Reading, Scranton and Shamokin, Pennsylvania; a bloodless general strike in St. Louis, Missouri; and a short lived uprising in Chicago, Illinois. In the worst case, rioting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania left 61 dead and 124 injured. Much of the city's center was burned, including more than a thousand rail cars destroyed. What began as the peaceful actions of organized labor attracted the masses of discontented and unemployed workers spawned by the depression, along with others who took opportunistic advantage of the chaos. In total, an estimated 100,000 workers participated nationwide.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brecher, Jeremy (1974). Strike!. Fawcett Publications. OCLC 730963168.

- ↑ Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. Perennial Classics.

- ↑ Tylecote, Andrew (1993). The long wave in the world economy. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 9780415036900.

- ↑ Kleppner, Paul (1973). "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties". In Schlesinger, Arthur M. History of U.S. Political Parties: Volume II, 1860–1910. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 1556. ISBN 9780835205948.

- ↑ Glasner, David; Cooley, Thomas F. (1997). "Depression of 1873–1879". Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0-8240-0944-1.

- ↑ Katz, Philip Mark (1998). Appomattox to Montmartre: Americans and the Paris Commune. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-674-32348-3.

- ↑ Laurie, Clayton (July 15, 1997). The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877–1945. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Kunkle, Fredrick (September 4, 2017). "Labor Day's violent roots: How a worker revolt on the B&O Railroad left 100 people dead". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

Further reading

- "Reign of the Rabble: the St. Louis General Strike of 1877" by David T. Burbank, published by August M. Kelley (1966)

- Philip S. Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877, New York: Monad Press, 1977.

- David Roediger (1985). "'Not Only the Ruling Classes to Overcome, but Also the So-Called Mob': Class, Skill and Community in the St. Louis General Strike of 1877". Journal of Social History. 19. doi:10.1353/jsh/19.2.213. JSTOR 3787468.

External links

.jpg)