Cooper (profession)

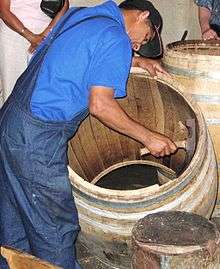

A cooper is a person trained to make wooden casks, barrels, vats, buckets, tubs, troughs and other staved containers, from timber that was usually heated or steamed to make it pliable. Journeymen coopers also traditionally made wooden implements, such as rakes and wooden bladed shovels. Other materials, such as iron, were used as well as wood, in the manufacturing process.

Etymology

The word "cooper" is derived from Middle Dutch or Middle Low German kūper 'cooper' from kūpe 'cask', in turn from Latin cupa 'tun, barrel'.[1] Everything a cooper produces is referred to collectively as cooperage. A cask is any piece of cooperage containing a bouge, bilge, or bulge in the middle of the container. A barrel is a type of cask, so the terms "barrel-maker" and "barrel-making" refer to just one aspect of a cooper's work. The facility in which casks are made is also referred to as a cooperage.

As a name

In much the same way as the trade or vocation of smithing produced the common English surname Smith and the German name Schmidt, the cooper trade is also the origin of the English name Cooper; French name Tonnelier and Tonnellier; Greek name Βαρελάς (Varelas); Danish name Bødker; German names like Binder and Faßbinder (literally cask binder), Böttcher (tub maker), Scheffler and Kübler; Dutch names like Kuiper or Cuypers; the Lithuanian name Kubilius; the Latvian name Mucenieks; the Hungarian name Kádár, Bodnár; Polish names such as Bednarz, Bednarski or Bednarczyk; the Czech name Bednář; the Romanian names Dogaru and Butnaru; Ukrainian family names such as Bodnar, Bodnaruk and Bodnarchuk as well as Бондаренко (Bondarenko); Russian/Ukrainian family names Бондарев (Bondarev) and Бочаров (Bocharov); the Jewish name Bodner; the Portuguese names Tanoeiro and Toneleiro; Spanish Cubero, Tonelero, and via Greek: Varela; Bulgarian Бъчваров (Bachvarov); Macedonian Бачваровски (Bacvarovski); Croatian Bačvar; and Italian name Bottai (from "botte").

History

.jpg)

Traditionally, a cooper is someone who makes wooden, staved vessels, held together with wooden or metal hoops and possessing flat ends or heads. Examples of a cooper's work include casks, barrels, buckets, tubs, butter churns, hogsheads, firkins, tierces, rundlets, puncheons, pipes, tuns, butts, pins and breakers. Traditionally, a hooper was the man who fitted the wooden or metal hoops around the barrels or buckets that the cooper had made, essentially an assistant to the cooper. The English name Hooper is derived from that profession. With time, many Coopers took on the role of the Hooper themselves.

There were four divisions in the cooper's craft. The "dry" or "slack" cooper made containers that would be used to ship dry goods such as cereals, nails, tobacco, fruits, and vegetables. The "dry-tight" cooper made casks designed to keep dry goods in and moisture out. Gunpowder and flour casks are examples of a dry-tight cooper's work. The "white" cooper made straight-staved containers like washtubs, buckets, and butter churns, which would hold water and other liquids but did not allow shipping of the liquids. Usually there was no bending of wood involved in white cooperage. The "wet" or "tight" cooper made casks for long-term storage and transportation of liquids that could even be under pressure, as with beer. The "general" cooper worked on ships, on the docks, in breweries, wineries and distilleries, and in warehouses, and was responsible for cargo while in storage or transit.

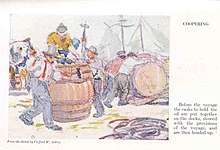

Ships, in the age of sail, provided much work for coopers. They made water and provision casks, used to sustain crew and passengers on long voyages. They also made barrels to contain high value commodities, such as wine and sugar. The proper stowage of casks on ships about to sail was an important stevedoring skill. Casks of various sizes were used to accommodate the sloping walls of the hull and make maximum use of limited space. Casks also had to be tightly packed, to ensure they did not move during the voyage and endanger the ship, crew and cask contents.[3] Whaling ships in particular, featuring long voyages and large crews, needed many casks, for salted meat, other provisions and water, and to store the whale oil. Sperm whale oil was a particularly difficult substance to contain, due to its highly viscus nature, and oil coopers were perhaps the most skilled tradesmen in pre-industrial cooperage.[4] Whaling ships usually carried a cooper on board, to assemble shooks and maintain casks.[5]

Coopers in Britain started to organise themselves as early as 1298.[6] The Worshipful Company of Coopers, one of the oldest Livery Companies in London, still survives, although it is now largely a charitable organisation.

Prior to the mid-20th century, the cooper's trade flourished in America; a dedicated trade journal was published, the National Cooper's Journal, with advertisements from many different firms that hoped to supply anything from barrel staves to purpose-built machinery. Plastics, stainless steel, pallets, and corrugated cardboard replaced most wooden containers during the last half of the 20th century, and largely made the cooperage trade obsolete.

21st century

In the 21st century, coopers mostly operate barrel-making machinery and assemble casks for the wine and spirits industry.

In the United Kingdom, the trade of master cooper is dwindling; it is thought that the last remaining cooper company in England is a beer barrel manufacturer in Wetherby, West Yorkshire.[7][8]

References

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 2002. 5th ed. Vol. 1, A–M. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 513.

- ↑ Obermair, Hannes (1999), "Das Bozner Stadtbuch: Handschrift 140 – das Amts- und Privilegienbuch der Stadt Bozen", in Stadtarchiv Bozen, Bozen: von den Grafen von Tirol bis zu den Habsburgern, Forschungen zur Bozner Stadtgeschichte, 1, Bozen-Bolzano: Verlagsanstalt Athesia, pp. 399–432 (415), ISBN 88-7014-986-2

- ↑ Thomas Rothwell Taylor, Stowage of ship cargoes, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1920, p.44.

- ↑ Mark Howard, “Coopers and casks in the whaling trade, 1800-1850,” The Mariner’s Mirror, 82 (4) p.438.

- ↑ Charles Reichman, "The whaling cooper," The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, 41 (4) December 1988, p.75.

- ↑ The Worshipful Company of Coopers - History

- ↑ "England's last master cooper seeks apprentice". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Are these England's last traditional craftsmen and women?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Coyne, Franklin E. (1941). The development of the cooperage industry in the United States, 1620-1940. Chicago.

- Kilby, Kenneth (1971). The cooper and his trade. London.

- Wagner, J.B. (1910). Cooperage; a treatise on modern shop practice and methods; from the tree to the finished article. Yonkers, NY.

- National cooper's journal, vol. 38

Further reading

External links

- Japanese cooper from Kyoto