São Tomé and Príncipe

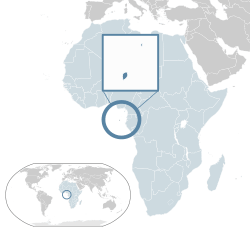

São Tomé and Príncipe (/ˌsaʊ təˈmeɪ ... ˈprɪnsɪpə, -peɪ/;[9] Portuguese: [sɐ̃w̃ tuˈmɛ i ˈpɾĩsɨpɨ]), (English: Saint Thomas and Prince) officially the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, is an island country in the Gulf of Guinea, off the western equatorial coast of Central Africa. It consists of two archipelagos around the two main islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, about 140 km (87 mi) apart and about 250 and 225 km (155 and 140 mi) off the northwestern coast of Gabon, respectively.

Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe | |

|---|---|

Flag

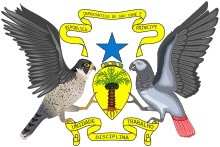

Coat of arms

| |

Motto: "Unidade, Disciplina, Trabalho" (Portuguese) "Unity, Discipline, Labour" | |

Anthem: Independência total Total Independence | |

Location of São Tomé and Príncipe (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) | |

_-_STP_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | São Tomé 0°20′N 6°44′E |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Recognised regional languages |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[2] |

• President | Evaristo Carvalho |

• Prime Minister | Jorge Bom Jesus |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• from Portugal | 12 July 1975 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,001[3] km2 (386 sq mi) (171th) |

• Water (%) | Negligible |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 211,028[4][5] (178th) |

• 2012 census | 178,739 |

• Density | 199.7/km2 (517.2/sq mi) (69th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $685 million[6] |

• Per capita | $3,220[6] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $355 million[6] |

• Per capita | $1,668[6] |

| Gini (2010) | 33.9[7] medium |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 137th |

| Currency | Dobra (STN) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +239 |

| ISO 3166 code | ST |

| Internet TLD | .st |

The islands were uninhabited until their discovery by Portuguese explorers in the 15th century. Gradually colonized and settled by the Portuguese throughout the 16th century, they collectively served as a vital commercial and trade center for the Atlantic slave trade. The rich volcanic soil and close proximity to the Equator made São Tomé and Príncipe ideal for sugar cultivation, followed later by cash crops such as coffee and cocoa; the lucrative plantation economy was heavily dependent upon imported African slaves. Cycles of social unrest and economic instability throughout the 19th and 20th centuries culminated in peaceful independence in 1975. São Tomé and Príncipe has since remained one of Africa's most stable and democratic countries.

With a population of 201,800 (2018 official estimate),[10][4] São Tomé and Príncipe is the second-smallest African sovereign state after Seychelles, as well as the smallest Portuguese-speaking country. Its people are predominantly of African and mestiço descent, with most practicing Roman Catholicism. The legacy of Portuguese rule is also visible in the country's culture, customs, and music, which fuse European and African influences. São Tomé and Príncipe is a founding member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.

History

Arrival of Europeans

.jpg)

The islands of São Tomé and Príncipe were uninhabited when the Portuguese arrived sometime around 1470. The first Europeans to put ashore were João de Santarém and Pêro Escobar. Portuguese navigators explored the islands and decided that they would be good locations for bases to trade with the mainland.

The dates of European arrival are sometimes given as 21 December (St Thomas's Day) 1471, for São Tomé; and 17 January (St Antony's Day) 1472, for Príncipe, though other sources cite different years around that time. Príncipe was initially named Santo Antão ("Saint Anthony"), changing its name in 1502 to Ilha do Príncipe ("Prince's Island"), in reference to the Prince of Portugal to whom duties on the island's sugar crop were paid.

The first successful settlement of São Tomé was established in 1493 by Álvaro Caminha, who received the land as a grant from the crown. Príncipe was settled in 1500 under a similar arrangement. Attracting settlers proved difficult, however, and most of the earliest inhabitants were "undesirables" sent from Portugal, mostly Jews.[11] In time, these settlers found the volcanic soil of the region suitable for agriculture, especially the growing of sugar.

Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe

By 1515, São Tomé and Príncipe had become slave depots for the coastal slave trade centered at Elmina.[12]

.jpg)

The cultivation of sugar was a labour-intensive process and the Portuguese began to enslave large numbers of Africans from the mainland. These slaves originated mainly from the Niger Delta and in Kongo.[13] Originally, the residents of São Tomé focused on cultivating provisions for themselves, sustaining their slaves, and participating in the export of slaves. A lack of value existed for the property on the island, as before the sugar boom, not much incentive remained to own land.[14] Foodstuffs often had to be imported, as cultivation on São Tomé was limited. The low value of property is emphasized by the death of a São Toméan landowner, Álvaro Borges in November, 1504.[14] When Borges passed, his cleared land and domesticated animals were sold for merely 13,000 réis at a time when four slaves could be bought for 19,400 réis.[15] Although São Tomé, according to Valentim Fernandes around 1506, had bountiful sugarcane fields and even larger sugarcane than Madeira "from which they already produce molasses,"[16] the island was absent of the facilities needed for industrial levels of sugar production.[14]

São Tomé would only became economically noteworthy with the introduction of a land grant in 1515 of a water-powered sugar mill.[17] Just two years later in 1517, Portuguese documents highlighted the importance of these sugar mills in the mass cultivation of sugar.[17] The documents state, "The fields are expanding and the sugar mills, too. At this time, only two sugar mills are here and another three are being built, counting the mill of the contractors, which is large. Similarly, the necessary conditions exist, such as streams and timber, to be able to build many more. And the [sugar] canes are the biggest I have ever seen in my life." The expansion of sugar fields and production in São Tomé led to the creation of plantation[s].[18] The creation of plantations resulted in an economic surge of sugar through slave labor. Consequently, São Tomé's economy was based in sugar production and the slave trade. By the mid-16th century, the Portuguese settlers had turned the islands into Africa's foremost exporter of sugar.

Slaves in São Tomé were bought from the Slave Coast of West Africa, the Niger Delta, the island Fernando Po, then later from the Kongo and Angola.[19] In the 16th century, the enslaved were imported from and exported to Portugal, Elmina, the Kingdom of Kongo, Angola, and the Spanish Americas. In 1510, reportedly 10,000 to 12,000 slaves were imported by Portugal.[20] Then in 1516, São Tomé received 4,072 slaves with the purpose of re-exportation.[20] As a result, in 1519 the island became the center of the slave trade between Elmina and the Niger Delta up until 1540.[21] Throughout the early to mid sixteenth century, São Tomé was additionally harboring slave trade relationships intermittently with Angola and the Kingdom of Kongo.[22] Furthermore, in 1525 São Tomé began its slave trade relationship with the Spanish Americas.[23] Most of the slaves to the Spanish Americas went to the Caribbean and Brazil. In the period between 1532 and 1536, every year São Tomé sent an average of 342 slaves to the Antilles.[24] Prior to 1580, the island accounted for 75 percent of Brazil's imports, mainly exporting slaves.[24] The slave trade was a cornerstone of São Tomé's economy all the way until the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The power dynamics of São Tomé in the 16th century were surprisingly diverse with the participation of free mulatto[s] and black citizens in governance. Due to the minimal amounts of voluntary colonists, who actively avoided inhabiting São Tomé because of the presence of disease and food shortages, the crown deported convicts to the island and encouraged interracial relationships to secure the settlement. Slavery was also not permanent, as demonstrated through the 1515 royal decree granting the manumission to African wives of white settlers and their mixed-race children.[25] Then in 1517, another royal decree freed the male slaves who had originally arrived on the island with the first colonists.[25] After 1520, a royal charter allowed for property-owning, married, free mulattos to hold public offices.[25] This was followed by a royal decree in 1546 that equated these qualified mulattos with the white settlers.[25] Consequently, free mulattos and black citizens enjoyed opportunities for upward mobility and participated in local politics and economy. Compounded with the participation of deported convicts and white settlers in government, frequent disputes occurred in the governance of São Tomé, which consisted of town councils, a governor, and a bishop.[26] These quarrels meant that São Tomé was constantly politically unstable.

Slavery in São Tomé was originally much less structured because of the scarcity of resources on the island. In the mid-16th century, an anonymous Portuguese pilot noted that the slaves were employed as couples, built their own accommodations, and worked autonomously once a week on the cultivation of their own food supply.[27] However, this more relaxed slave system did not last long following the introduction of plantations. From the onset of slavery in São Tomé, slaves frequently ran away to the mountainous interior of the island.[28] Between 1514 and 1527, five percent of slaves that were imported to São Tomé escaped.[28] These runaway slaves frequently starved to death, as there were few crops and edible animals in the tropical mountains of the island.[29] Ironically, the lack of food on the sugar plantations especially between 1531 and 1535 was one of the main reasons slaves attempted to escape.[29] Eventually, the Maroon (people) developed settlements in the interior of the island known as macambos.[29]

The first signs of slave rebellion began in the 1530s, when the maroon gangs organized and attacked plantations.[29] As a result, more plantations were abandoned. The attacks became so common that a formal complaint was lodged by local Portuguese authorities in 1531 claiming that too many settlers and black citizens were being killed in the fights, and that the island would be lost if the problem remained unresolved.[29] As a solution, in 1533 local authorities engaged in a 'bush war' led by a 'bush captain' using militia units to suppress the maroon combatants.[29] A significant event in the maroon fight for freedom occurred in 1549, when two men claiming to have been born free men from the macambos were taken in by a wealthy mulatto planter named Ana de Chaves.[29] With the support of de Chaves, the two men sent in a petition to the king to be labeled free men instead of slaves. The monarch ended up approving the request. The largest occurrence of marronage happened simultaneously to the sugar boom of the mid-16th century, when the number of plantation slaves increased exponentially.[29] Between 1587 and 1590, many of the runaway slaves were defeated as a result of the bush war.[30] However, in 1593 the slaves regrouped and reorganized only for later that year, according to the governor at the time, to be almost completely extinguished.[31] Despite the counter-revolutionary efforts by the authorities, the settlers were unable to inhabit the southern and western parts of São Tomé, because of their proximity to the maroons. The greatest slave revolt in São Tomé occurred in July 1595, during a period when the government was weakened by disputes between the bishop and the governor.[30] The revolt, which was headed by a native slave named Amador, was successful in uniting 5000 slaves in an effort to raid and destroy plantations, sugar mills, and settler's houses.[30] Amador and his rebellion unsuccessfully attempted to raid the town three times before eventually, after three weeks, they were defeated by the militia.[30] Two hundred slaves were killed in combat, and Amador and the other rebel leaders were executed.[30] The rest of the slaves were granted amnesty and returned to their plantations. Amador's revolt had successfully destroyed 60 of the island's 85 sugar mills in one of the greatest slave uprisings in history.[30] Smaller slavery rebellions followed in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Eventually, competition from sugar-producing colonies in the Western Hemisphere began to hurt the islands. The large enslaved population also proved difficult to control, with Portugal unable to invest many resources in the effort. Sugar cultivation thus declined over the next 100 years, and by the mid-17th century, the economy of São Tomé had changed. It was now primarily a transit point for ships engaged in the slave trade between the West and continental Africa.

In the early 19th century, two new cash crops, coffee and cocoa, were introduced. The rich, volcanic soils proved well suited to the new cash crop industry, and soon extensive plantations (known as roças), owned by Portuguese companies or absentee landlords, occupied almost all of the good farmland.[citation needed] By 1908, São Tomé had become the world's largest producer of cocoa, which remains the country's most important crop.

The roças system, which gave the plantation managers a high degree of authority, led to abuses against the African farm workers. Although Portugal officially abolished slavery in 1876, the practice of forced paid labour continued. Scientific American documented in words and pictures the continued use of slaves in São Tomé in its 13 March 1897 issue.

In the early 20th century, an internationally publicized controversy arose over charges that Angolan contract workers were being subjected to forced labour and unsatisfactory working conditions. Sporadic labor unrest and dissatisfaction continued well into the 20th century, culminating in an outbreak of riots in 1953 in which several hundred African laborers were killed in a clash with their Portuguese rulers. This "Batepá Massacre" remains a major event in the colonial history of the islands, and its anniversary is officially observed by the government.

Independence (1975)

.jpg)

By the late 1950s, when other emerging nations across the African continent demanded their independence, a small group of São Toméans had formed the Movement for the Liberation of São Tomé and Príncipe (MLSTP), which eventually established its base in nearby Gabon. Picking up momentum in the 1960s, events moved quickly after the overthrow of the Caetano dictatorship in Portugal in April 1974.

The new Portuguese regime was committed to the dissolution of its overseas colonies. In November 1974, their representatives met with the MLSTP in Algiers and worked out an agreement for the transfer of sovereignty. After a period of transitional government, São Tomé and Príncipe achieved independence on 12 July 1975, choosing as the first president the MLSTP Secretary General Manuel Pinto da Costa.

In 1990, São Tomé became one of the first African countries to undergo democratic reform, and changes to the constitution – the legalization of opposition political parties – led to elections in 1991 that were nonviolent, free, and transparent. Miguel Trovoada, a former prime minister who had been in exile since 1986, returned as an independent candidate and was elected president. Trovoada was re-elected in São Tomé's second multiparty presidential election in 1996.

The Party of Democratic Convergence won a majority of seats in the National Assembly, with the MLSTP becoming an important and vocal minority party. Municipal elections followed in late 1992, in which the MLSTP won a majority of seats on five of seven regional councils. In early legislative elections in October 1994, the MLSTP won a plurality of seats in the assembly. It regained an outright majority of seats in the November 1998 elections.

Presidential elections were held in July 2001. The candidate backed by the Independent Democratic Action party, Fradique de Menezes, was elected in the first round and inaugurated on 3 September. Parliamentary elections were held in March 2002. For the next four years, a series of short-lived opposition-led governments was formed.

The army seized power for one week in July 2003, complaining of corruption and that forthcoming oil revenues would not be divided fairly. An accord was negotiated under which President de Menezes was returned to office. The cohabitation period ended in March 2006, when a propresidential coalition won enough seats in National Assembly elections to form a new government.[32]

In the 30 July 2006 presidential election, Fradique de Menezes easily won a second five-year term in office, defeating two other candidates Patrice Trovoada (son of former President Miguel Trovoada) and independent Nilo Guimarães. Local elections, the first since 1992, took place on 27 August 2006 and were dominated by members of the ruling coalition. On 12 February 2009, a coup d'état was attempted to overthrow President Fradique de Menezes. The plotters were imprisoned, but later received a pardon from President de Menezes.[33]

Politics

.jpg)

The president of the republic is elected to a five-year term by direct universal suffrage and a secret ballot, and must gain an outright majority to be elected. The president may hold up to two consecutive terms. The prime minister is appointed by the president, and the 14 members of cabinet are chosen by the prime minister.

The National Assembly, the supreme organ of the state and the highest legislative body, is made up of 55 members, who are elected for a four-year term and meet semiannually. Justice is administered at the highest level by the Supreme Court. The judiciary is independent under the current constitution.

Political culture

São Tomé and Príncipe has functioned under a multiparty system since 1990. With regard to human rights, there are freedom of speech and the freedom to form opposition political parties.

São Tomé and Príncipe finished 11th out of the African countries measured by the Ibrahim Index of African Governance in 2010, a comprehensive reflection of the levels of governance in Africa.[34]

Foreign relations

São Tomé and Príncipe has embassies in Angola, Belgium, Gabon, Portugal, and the United States. It recognized the People's Republic of China in 2016. It also has a permanent mission to the UN in New York City and an International Diplomatic Correspondent Office.

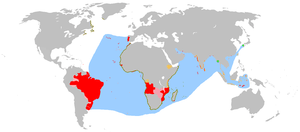

São Tomé and Príncipe is a founding member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, and international organization and political association of Lusophone nations across four continents, where Portuguese is an official language.

Military

São Tomé and Príncipe's military is small and consists of four branches: the Army (Exército), Coast Guard (Guarda Costeira also called "Navy"), Presidential Guard (Guarda Presidencial), and the National Guard.

In 2017, São Tomé and Príncipe signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[35]

Administrative divisions

In 1977, two years after independence, the country was divided into two provinces (São Tomé Province and Príncipe Province) and six districts. Since the new constitution was adopted in 1990, the provinces have been abolished, and the districts are the only administrative subdivisions. Since 29 April 1995, the island of Príncipe is an autonomous region, coterminous with the district of Pagué. The larger island of São Tomé is divided into six districts and Príncipe island into one:[36]

São Tomé Island

- Água Grande

- Cantagalo

- Caué

- Lembá

- Lobata

- Mé-Zóchi

Príncipe Island

- Pagué

Geography

The islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, situated in the equatorial Atlantic and Gulf of Guinea about 300 and 250 km (190 and 160 mi), respectively, off the northwest coast of Gabon, constitute Africa's second-smallest country. Both are part of the Cameroon volcanic mountain line, which also includes the islands of Annobón to the southwest, Bioko to the northeast (both part of Equatorial Guinea), and Mount Cameroon on the coast of Gulf of Guinea.

São Tomé is 50 km (30 mi) long and 30 km (20 mi) wide and the more mountainous of the two islands. Its peaks reach 2,024 m (6,640 ft) – Pico de São Tomé. Príncipe is about 30 km (20 mi) long and 6 km (4 mi) wide. Its peaks reach 948 m (3,110 ft) – Pico de Príncipe. Swift streams radiating down the mountains through lush forest and cropland to the sea cross both islands. The Equator lies immediately south of São Tomé Island, passing through the islet Ilhéu das Rolas.

The Pico Cão Grande (Great Dog Peak) is a landmark volcanic plug peak, at 0°7′0″N 6°34′00″E in southern São Tomé. It rises over 300 m (1,000 ft) above the surrounding terrain and the summit is 663 m (2,175 ft) above sea level.

Climate

At sea level, the climate is tropical—hot and humid with average yearly temperatures of about 27 °C (80.6 °F) and little daily variation. The temperature rarely rises beyond 32 °C (89.6 °F). At the interior's higher elevations, the average yearly temperature is 20 °C (68 °F), and nights are generally cool. Annual rainfall varies from 5,000 mm (196.9 in) on the southwestern slopes to 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in the northern lowlands. The rainy season is from October to May.

Wildlife

São Tomé and Príncipe does not have a large number of native mammals (although the São Tomé shrew and several bat species are endemic). The islands are home to a larger number of endemic birds and plants, including the world's smallest ibis (the São Tomé ibis), the world's largest sunbird (the giant sunbird), the rare São Tomé fiscal, and several giant species of Begonia. São Tomé and Principe is an important marine turtle-nesting site, including the hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata).

Economy

.jpg)

Since the 19th century, the economy of São Tomé and Príncipe has been based on plantation agriculture. At the time of independence, Portuguese-owned plantations occupied 90% of the cultivated area. After independence, control of these plantations passed to various state-owned agricultural enterprises. The main crop on São Tomé is cocoa, representing about 95% of agricultural exports. Other export crops include copra, palm kernels, and coffee.

Domestic food-crop production is inadequate to meet local consumption, so the country imports most of its food.[37] In 1997, an estimated 90% of the country's food needs are met through imports.[37] Efforts have been made by the government in recent years to expand food production, and several projects have been undertaken, largely financed by foreign donors.

.jpg)

Other than agriculture, the main economic activities are fishing and a small industrial sector engaged in processing local agricultural products and producing a few basic consumer goods. The scenic islands have potential for tourism, and the government is attempting to improve its rudimentary tourist industry infrastructure. The government sector accounts for about 11% of employment.

Following independence, the country had a centrally directed economy, with most means of production owned and controlled by the state. The original constitution guaranteed a mixed economy, with privately owned cooperatives combined with publicly owned property and means of production.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the economy of São Tomé encountered major difficulties. Economic growth stagnated, and cocoa exports dropped in both value and volume, creating large balance-of-payments deficits. Plantation land was seized, resulting in the complete collapse of cocoa production. At the same time, the international price of cocoa slumped.

In response to its economic downturn, the government undertook a series of far-reaching economic reforms. In 1987, the government implemented an International Monetary Fund structural adjustment program, and invited greater private participation in management of the parastatals, as well as in the agricultural, commercial, banking, and tourism sectors. The focus of economic reform since the early 1990s has been widespread privatization, especially of the state-run agricultural and industrial sectors.

The São Toméan government has traditionally obtained foreign assistance from various donors, including the UN Development Programme, the World Bank, the European Union, Portugal, Taiwan, and the African Development Bank. In April 2000, in association with the Banco Central de São Tomé e Príncipe, the IMF approved a poverty-reduction and growth facility for São Tomé aimed at reducing inflation to 3% for 2001, raising ideal growth to 4%, and reducing the fiscal deficit.

In late 2000, São Tomé qualified for significant debt reduction under the IMF–World Bank's Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative. The reduction is being reevaluated by the IMF, due to the attempted coup d'état in July 2003 and subsequent emergency spending. Following the truce, the IMF decided to send a mission to São Tomé to evaluate the macroeconomic state of the country. This evaluation is ongoing, reportedly pending oil legislation to determine how the government will manage incoming oil revenues, which are still poorly defined, but in any case expected to change the economic situation dramatically.

In parallel, some efforts have been made to incentivize private tourism initiatives, but their scope remains limited.[38]

São Tomé also hosts a broadcasting station of the American International Broadcasting Bureau for the Voice of America[39] at Pinheira.[40]

Portugal remains one of São Tomé's major trading partners, particularly as a source of imports. Food, manufactured articles, machinery, and transportation equipment are imported primarily from the EU.

São Tomé and Príncipe was ranked the 174th-safest investment destination in the world in the March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings.[41]

Petroleum exploration

.jpg)

In 2001, São Tomé and Nigeria reached agreement on joint exploration for petroleum in waters claimed by the two countries of the Niger Delta geologic province. After a lengthy series of negotiations, in April 2003, the joint development zone (JDZ) was opened for bids by international oil firms. The JDZ was divided into nine blocks; the winning bids for block one, ChevronTexaco, ExxonMobil, and the Norwegian firm, Equity Energy, were announced in April 2004, with São Tomé to take in 40% of the $123 million bid, and Nigeria the other 60%. Bids on other blocks were still under consideration in October 2004. São Tomé has received more than $2 million from the bank to develop its petroleum sector.[42]

Banking

Banco Central de Sāo Tomé e Príncipe is the central bank, responsible for monetary policy and bank supervision. Six banks are in the country; the largest and oldest is Banco Internacional de São Tomé e Príncipe, which is a subsidiary of Portugal's government-owned Caixa Geral de Depósitos. It had a monopoly on commercial banking until a change in the banking law in 2003 led to the entry of several other banks.

Society

Demographics

_(4).jpg)

.jpg)

The total population is estimated at 201,800 in May 2018 by the government agency.[10] About 193,380 people live on São Tomé and 8,420 on Príncipe. Natural increase is about 4,000 people per year.

Nearly all are descended from people from different countries taken to the islands by the Portuguese from 1470 onwards. In the 1970s, two significant population movements occurred — the exodus of most of the 4,000 Portuguese residents and the influx of several hundred São Tomé refugees from Angola.

Ethnic groups

Distinct ethnic groups on São Tomé and Príncipe include:

- Mestiços, or mixed-blood, are descendants of Portuguese colonists and African slaves brought to the islands during the early years of settlement from Benin, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Angola (these people also are known as filhos da terra or "children of the land").

- Angolares are reputedly descendants of Angolan slaves who survived a 1540 shipwreck and now earn their livelihood fishing.

- Forros are descendants of freed slaves when slavery was abolished.

- Serviçais are contract laborers from Angola, Mozambique, and Cape Verde, living temporarily on the islands.

- Tongas are children of serviçais born on the islands.

- Europeans, primarily Portuguese

- Asians, mostly Chinese, including Macanese people of mixed Portuguese and Chinese descent from Macau

Languages

Portuguese is the official and the de facto national language of São Tomé and Príncipe, with about 98.4% speaking it, a significant share as their native language, and it has been spoken in the islands since the end of the 15th century. Restructured variants of Portuguese or Portuguese creoles are also spoken: Forro, a creole language (36.2%), Cape Verdean Creole (8.5%), Angolar (6.6%), and Principense (1%). French (6.8%) and English (4.9%) are foreign languages taught in schools.

Religion

Religion in São Tomé and Príncipe [43]

The majority of residents belongs to the local branch of the Roman Catholic Church, which in turn retains close ties with the church in Portugal. Sizeable Protestant minorities of Seventh-day Adventists and other Evangelical Protestants exist, as well as a small but growing Muslim population.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Health

See Health in São Tomé and Príncipe

Education

Education in São Tomé and Príncipe is compulsory for four years.[44] Primary school enrollment and attendance rates were unavailable for São Tomé and Príncipe as of 2001.[44]

The educational system has a shortage of classrooms, insufficiently trained and underpaid teachers, inadequate textbooks and materials, high rates of repetition, poor educational planning and management, and a lack of community involvement in school management.[44] Domestic financing of the school system is lacking, leaving the system highly dependent on foreign financing.[44]

Tertiary institutions are the National Lyceum (São Tomé and Príncipe) and the University of São Tomé and Príncipe.

Culture

São Toméan culture is a mixture of African and Portuguese influences.

Music

São Toméans are known for ússua and socopé rhythms, while Príncipe is home to the dêxa beat. Portuguese ballroom may have played an integral part in the development of these rhythms and their associated dances.

Tchiloli is a musical dance performance that tells a dramatic story. The danço-Congo is similarly a combination of music, dance, and theatre.

Cuisine

Staple foods include fish, seafood, beans, maize, and cooked banana.[45][46] Tropical fruits, such as pineapple, avocado, and bananas, are significant components of the cuisine. The use of hot spices is prominent in São Tomése cuisine.[45] Coffee is used in various dishes as a spice or seasoning.[45] Breakfast dishes are often reheated leftovers from the previous evening's meal, and omelettes are popular.[46]

Sports

Football (soccer) is the most famous sport in São Tomé and Principe, the São Tomé and Príncipe national football team is the national association football team of São Tomé and Príncipe and is controlled by the São Toméan Football Federation. It is a member of the Confederation of African Football (CAF) and FIFA.[47]

See also

- ISO 3166-2:ST

- Outline of São Tomé and Príncipe

- List of São Tomé and Príncipe-related topics

References

- "Nationality". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- Octávio Amorim Neto; Marina Costa Lobo (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 1644026. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Ministério Dos Negócios Estrangeiros e Comunidades da República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe". Archived from the original on 2019-03-08. Retrieved 2017-11-10.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "São Tomé and Príncipe". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- "GINI index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "2016 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "São Tomé – Definition of São Tomé". Yourdictionary.com. 2013-09-25. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística de São Tomé e Príncipe, as at 13 May 2018.

- "The Expulsion 1492 Chronicles, section XI: "The Vale of Tears", quoting Joseph Hacohen (1496–1577); also, section XVII, quoting 16th century author Samuel Usque". Aish.com. 2009-08-04. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- Ivor Wilks and Akan Wangara (January 1997). "Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries". In Peter John Bakewell (ed.). Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Variorum. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-86078-513-2.

- Vogt, John L. "The Early Sao Tome-Principe Slave Trade with Mina, 1500-1540." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 6, no. 3 (1973): 453-67. doi:10.2307/216611.

- Caldeira, Arlindo Manuel. "LEARNING THE ROPES IN THE TROPICS: SLAVERY AND THE PLANTATION SYSTEM ON THE ISLAND OF SÃO TOMÉ." African Economic History 39 (2011): 41. JSTOR 23718978.

- Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (hereinafter cited as TT), Corpo Cronológico, II, 15-77, inventory of the assets belonging to Álvaro Borges, 4 November 1507, a published copy of which is found in PMA, vol. V, 221-243.

- Th. Monod, A. Teixeira da Mota, and R. Mauny, eds., Description de la Côte Occidentale d'Afrique par Valentim Fernandes (Bissau: Centro de Estudos da Guiñé Portuguesa, 1951), 11

- Caldeira, Arlindo Manuel. "LEARNING THE ROPES IN THE TROPICS: SLAVERY AND THE PLANTATION SYSTEM ON THE ISLAND OF SÃO TOMÉ." African Economic History 39 (2011): 43. JSTOR 23718978.

- "As roças vâo em crescimento e os engenhos de açticaragora somente dois e fazem-se très com o dos tratadores [conassi há grande aparelho, assi de ribeiras como de lenha, par canas, as mais façanhosas que em minha vida vi": Letter from Segura to the monarch, 15 March 1517, in Antonio Brásio, édAfricana (hereinafter referred to as

- Vogt, John L. "The Early Sao Tome-Principe Slave Trade with Mina, 1500-1540." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 6, no. 3 (1973): 462. doi:10.2307/216611.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 66. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- Vogt, John L. "The Early Sao Tome-Principe Slave Trade with Mina, 1500-1540." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 6, no. 3 (1973): 467. {doi|10.2307/216611}}.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 67. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- Vogt, John L. "The Early Sao Tome-Principe Slave Trade with Mina, 1500-1540." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 6, no. 3 (1973): 466. doi:10.2307/216611.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 68. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 59. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- Seibert, Gerhard. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 60. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- For an English translation, see John William Blake, trans., ed., Europeans in West Africa, 1450–1560 (London, 1942), 145ff.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 63. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 64. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR stable/10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- SEIBERT, GERHARD. "São Tomé & Príncipe: The First Plantation Economy in the Tropics." In Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa, edited by Law Robin, Schwarz Suzanne, and Strickrodt Silke, 65. Boydell and Brewer, 2013. JSTOR stable/10.7722/j.ctt31nj49.10.

- Caldeira,‘Rebelião e Outras Formas de Resistência’, 111.

- Gerhard Seibert (2006), Comrades, Clients and Cousins: Colonialism, Socialism and Democratization in São Tomé and Príncipe, Leiden: Brill.

- Sao Tome president pardons coup plotter. Orange Botswana Portal. January 7, 2010.

- 2010 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2011, retrieved 2012-03-04

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Nunes Silva, Carlos (2016). "São Tomé and Príncipe". Governing Urban Africa. Springer Nature. pp. 35–39. ISBN 9781349951093 – via Google Books.

- Mary E. Lassanyi; Wayne Olson (1 July 1997). Agricultural Marketing Directory for U.S. & Africa Trade. DIANE Publishing. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-7881-4479-0. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Brígida Rocha Brito and others, Turismo em Meio Insular Africano: Potencialidades, constrangimentos e impactos, Lisbon: Gerpress, 2010 (in Portuguese)

- World Radio TV Handbook (WRTH) Vol. 49 • 1995, p. 162; Billboard Publications Archived 2013-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, Amsterdam 1995. ISBN 0-8230-5926-X

- WRTH 1997, p. 514, ISBN 0-8230-7797-7

- "Euromoney Country Risk". Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC. Archived from the original on 30 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Phuong Tran (1 February 2007). "São Tomé & Príncipe Still Waiting for Oil Boom". VOA News. Voice of America. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- São Tomé and Principe Archived 2014-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. pewforum.org.

- "São Tomé and Príncipe" Archived 2010-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- The Recipes of Africa. Dyfed Lloyd Evans. pp. 174–176. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- Kathleen Becker (23 July 2008). Sao Tome and Principe. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 74–79. ISBN 978-1-84162-216-3. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- "BBC Sport – Sao Tome e Principe rocket up Fifa rankings". Bbc.co.uk. 2012-03-07. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

Further reading

- Chabal, Patrick (ed.) 2002. A history of postcolonial Lusophone Africa. London: C. Hurst. ISBN 1-85065-589-8 – Overview of the decolonization of Portugal's African colonies, and a chapter specifically about São Tomé and Príncipe's experience since the 1970s.

- Eyzaguirre, Pablo B. "The independence of São Tomé e Príncipe and agrarian reform." Journal of Modern African Studies 27.4 (1989): 671-678.

- Frynas, Jędrzej George, Geoffrey Wood, and Ricardo MS Soares de Oliveira. "Business and politics in São Tomé e Príncipe: from cocoa monoculture to petro‐state." African Affairs 102.406 (2003): 51-80. online

- Hodges, Tony, and Malyn Dudley Dunn Newitt. São Tomé and Príncipe: from plantation colony to microstate (Westview Press, 1988).

- Keese, Alexander. "Forced labour in the 'Gorgulho Years': Understanding reform and repression in Rural São Tomé e Príncipe, 1945–1953." Itinerario 38.1 (2014): 103-124.

- Tomás, Gil, et al. "The peopling of Sao Tome (Gulf of Guinea): origins of slave settlers and admixture with the Portuguese." Human biology 74.3 (2002): 397-411.

- Weszkalnys, Gisa. "Hope & oil: expectations in São Tomé e Príncipe." Review of African Political Economy 35.117 (2008): 473-482. online

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for São Tomé and Príncipe. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to São Tomé and Príncipe. |

| Look up são tomé and príncipe in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Country Profile from BBC News

- "São Tomé and Príncipe". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- São Tomé and Príncipe at Curlie

- São Tomé e Príncipe—Tourist information

- Key Development Forecasts for São Tomé and Príncipe from International Futures

- Government

- Página Oficial do Governo de São Tomé e Príncipe – Official Page of the Government of São Tomé and Príncipe (in Portuguese)

- Presidência da República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe – President of the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe (official site) (in Portuguese)

- Assembleia Nacional de São Tomé e Príncipe – National Assembly of São Tomé and Príncipe (official site) (in Portuguese)

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística – National statistics institute (in Portuguese)

- Central Bank of São Tomé and Príncipe

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

.svg.png)