Samarkand

Samarkand (/ˈsæmərkænd/; Uzbek: Samarqand; Persian: سمرقند; Russian: Самарканд), alternatively Samarqand, is a city in south-eastern Uzbekistan and one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. There is evidence of human activity in the area of the city from the late Paleolithic era, though there is no direct evidence of when Samarkand was founded; some theories propose that it was founded between the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. Prospering from its location on the Silk Road between China and the Mediterranean, at times Samarkand was one of the greatest cities of Central Asia.[1]

Samarkand | |

|---|---|

City | |

_(5634467674).jpg)  .jpg) | |

Seal | |

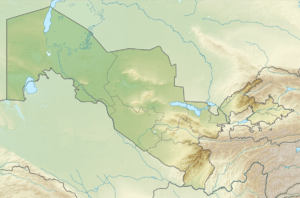

Samarkand Location in Uzbekistan  Samarkand Samarkand (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 39°42′N 66°59′E | |

| Country | |

| Vilayat | Samarkand Vilayat |

| Settled | 8th century BC |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Administration |

| • Body | Hakim (Mayor) |

| Area | |

| • City | 120 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 705 m (2,313 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • City | 530,400 |

| • Density | 4,400/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 950,000 |

| Demonym(s) | Samarkandian / Samarkandi |

| Time zone | UTC+5 |

| Postal code | 140100 |

| Website | samarkand.uz |

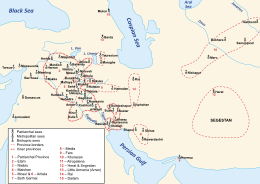

By the time of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, it was the capital of the Sogdian satrapy. The city was taken by Alexander the Great in 329 BC, when it was known by its Greek name of Marakanda (Μαράκανδα).[2] The city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic rulers until the Mongols under Genghis Khan conquered Samarkand in 1220. Today, Samarkand is the capital of Samarqand Region and one of the largest cities of Uzbekistan.[3]

The city is noted for being an Islamic center for scholarly study and the birthplace of the Timurid Renaissance. In the 14th century it became the capital of the empire of Timur (Tamerlane) and is the site of his mausoleum (the Gur-e Amir). The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, rebuilt during the Soviet era, remains one of the city's most notable landmarks. Samarkand's Registan square was the ancient centre of the city, and is bound by three monumental religious buildings. The city has carefully preserved the traditions of ancient crafts: embroidery, gold embroidery, silk weaving, engraving on copper, ceramics, carving and painting on wood.[4] In 2001, UNESCO added the city to its World Heritage List as Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures.

Modern Samarkand is divided into two parts: the old city, and the new city developed during the days of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. The old city includes historical monuments, shops and old private houses, while the new city includes administrative buildings along with cultural centres and educational institutions.[5]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Bibi-Khanym Mosque | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 603 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th session) |

| Area | 1,123 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,369 ha |

Etymology

The name originates in the Sogdian samar, "stone, rock", and kand, "fort, town".[6]

History

Early history

Along with Bukhara,[7] Samarkand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, prospering from its location on the trade route between China and the Mediterranean (Silk Road).

Archeological excavations held within the city limits (Syob and midtown) as well as suburban areas (Hojamazgil, Sazag'on) unearthed forty-thousand-year-old evidence of human activity, dating back to the Late Paleolithic era. A group of Mesolithic era (12th–7th millennium BC) archeological sites were discovered at Sazag'on-1, Zamichatosh and Okhalik (suburbs of the city). The Syob and Darg'om canals, supplying the city and its suburbs with water, appeared around the 7th to 5th centuries BC (early Iron Age). There is no direct evidence when Samarkand was founded. Researchers of the Institute of Archeology of Samarkand argue for the existence of the city between the 8th and 7th centuries BC.

Samarkand has been one of the main centres of Sogdian civilization from its early days. By the time of the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia it had become the capital of the Sogdian satrapy.

Hellenistic period

Alexander the Great conquered Samarkand in 329 BC. The city was known as Maracanda by the Greeks.[8] Written sources offer small clues as to the subsequent system of government.[9] They tell of an Orepius who became ruler "not from ancestors, but as a gift of Alexander".[10]

While Samarkand suffered significant damage during Alexander's initial conquest, the city recovered rapidly and flourished under the new Hellenic influence. There were also major new construction techniques; oblong bricks were replaced with square ones and superior methods of masonry and plastering were introduced.[11]

Alexander's conquests introduced classical Greek culture into Central Asia; for a time, Greek aesthetics heavily influenced local artisans. This Hellenistic legacy continued as the city became part of various successor states in the centuries following Alexander's death, i.e. the Seleucid Empire, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and Kushan Empire (even though the Kushana themselves originated in Central Asia). After the Kushan state lost control of Sogdia, during the 3rd century AD, Samarkand went into decline as a centre of economic, cultural and political power. It did not significantly revive until the 5th century AD.

Sassanian era

Samarkand was conquered by the Persian Sassanians around 260 AD. Under Sassanian rule, the region became an essential site for Manichaeism, and facilitated the dissemination of the religion throughout Central Asia.[12]

After the Hephtalites (Huns) conquered Samarkand, they controlled it until the Göktürks, in an alliance with the Sassanid Persians, won it at the Battle of Bukhara. The Turks ruled over Samarkand until they were defeated by the Sassanids during the Göktürk–Persian Wars.

Early Islamic era

After the Arab conquest of Iran, the Turks conquered Samarkand and held it until the Turkic Khaganate collapsed due to wars with the Chinese Tang Dynasty. During this time the city became a protectorate and paid tribute to the ruling Tang. The armies of the Umayyad Caliphate under Qutayba ibn Muslim captured the city in circa 710 from the Turks.[12] During this period, Samarkand was a diverse religious community and was home to a number of religions, including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, Judaism and Nestorian Christianity.[13] Central Asia was generally not settled with Arabs by Qutayba, who forced the local rulers to pay tribute but largely left them to their own devices; Samarkand was the major exception to this policy and an Arab garrison and administration was established in the city, its Zoroastrian fire temples were razed and a mosque was built.[14] Much of the population of the city converted to Islam.[15] As a long-term result, Samarkand developed into a center of Islamic and Arabic learning.[14]

Legend has it that during Abbasid rule,[16] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas in 751, which led to the foundation of the first paper mill of the Islamic world in Samarkand. The invention then spread to the rest of the Islamic world, and from there to Europe.

Abbasid control of Samarkand soon dissipated and was replaced with that of the Samanids (862–999), though the Samanids were still nominal vassals of the Caliph during their control of Samarkand. Under Samanid rule the city became one of the capitals of the Samanid dynasty and an even more important link amongst numerous trade routes. The Samanids were overthrown by the Karakhanids around 1000. During the next two hundred years, Samarkand would be ruled by a succession of Turkic tribes, including the Seljuqs and the Khwarazm-Shahs.[17]

The 10th-century Iranian author Istakhri, who travelled in Transoxiana, provides a vivid description of the natural riches of the region he calls "Smarkandian Sogd":

I know no place in it or in Samarkand itself where if one ascends some elevated ground one does not see greenery and a pleasant place, and nowhere near it are mountains lacking in trees or a dusty steppe... Samakandian Sogd... [extends] eight days travel through unbroken greenery and gardens... . The greenery of the trees and sown land extends along both sides of the river [Sogd]... and beyond these fields is pasture for flocks. Every town and settlement has a fortress... It is the most fruitful of all the countries of Allah; in it are the best trees and fruits, in every home are gardens, cisterns and flowing water.

Mongol period

The Mongols conquered Samarkand in 1220. Although Genghis Khan "did not disturb the inhabitants [of the city] in any way", according to Juvaini he killed all who took refuge in the citadel and the mosque, pillaged the city completely and conscripted 30,000 young men along with 30,000 craftsmen. Samarkand suffered at least one other Mongol sack by Khan Baraq to get treasure he needed to pay an army. It remained part of the Chagatai Khanate (one of four Mongol successor realms) until 1370.

The Travels of Marco Polo, where Polo records his journey along the Silk Road in the late 13th century, describes Samarkand as "a very large and splendid city..."

The Yenisei area had a community of weavers of Chinese origin and Samarkand and Outer Mongolia both had artisans of Chinese origin seen by Changchun.[18] After the Mongol conquest of Central Asia by Genghis Khan, foreigners were chosen as administrators and co-management with Chinese and Qara-Khitays (Khitans) of gardens and fields in Samarqand was put upon the Muslims as a requirement since Muslims were not allowed to manage without them.[19][20]

The khanate allowed the establishment of Christian bishoprics (see below).

Timur(id) rule (14th-15th centuries)

Ibn Battuta visited in 1333, and called the city "one of the greatest and finest of cities, and most perfect of them in beauty." He also noted the orchards were supplied water via norias.[21]

In 1365, a revolt against Chagatai Mongol control occurred in Samarkand.[22]

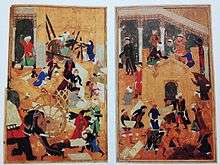

In 1370 the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), the founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire, made Samarkand his capital. During the next 35 years, he rebuilt most of the city and populated it with the great artisans and craftsmen from across the empire. Timur gained a reputation as a patron of the arts and Samarkand grew to become the centre of the region of Transoxiana. Timur's commitment to the arts is evident in the way he was ruthless with his enemies but merciful towards those with special artistic abilities, sparing the lives of artists, craftsmen and architects so that he could bring them to improve and beautify his capital. He was also directly involved in his construction projects and his visions often exceeded the technical abilities of his workers. Furthermore, the city was in a state of constant construction and Timur would often request buildings to be done and redone quickly if he was unsatisfied with the results.[23] Timur made it so that the city could only be reached by roads and also ordered the construction of deep ditches and walls, that would run 8 kilometres (5 miles) in circumference, separating the city from the rest of its surrounding neighbors.[24] During this time the city had a population of about 150,000.[25] This great period of reconstruction is encapsulated in the account of Henry III's ambassador, Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, who was stationed there between 1403 and 1406. During his stay the city was typically in a constant state of construction. "The Mosque which Timur had caused to be built in memory of the mother of his wife...seemed to us the noblest of all those we visited in the city of Samarkand, but no sooner had it been completed than he begun to find fault with its entrance gateway, which he now said was much too low and must forthwith be pulled down."[26]

Between 1424 and 1429, the great astronomer Ulugh Beg built the Samarkand Observatory. The sextant was 11 metres long and once rose to the top of the surrounding three-storey structure, although it was kept underground to protect it from earthquakes. Calibrated along its length, it was the world's largest 90-degree quadrant at the time.[27] However, the observatory was destroyed by religious fanatics in 1449.[27][28]

Post-Timurid regional rulers

In 1500 the Uzbek nomadic warriors took control of Samarkand.[25] The Shaybanids emerged as the Uzbek leaders at or about this time.

In the second quarter of the 16th century, the Shaybanids moved their capital to Bukhara and Samarkand went into decline. After an assault by the Afshar Shahanshah Nader Shah the city was abandoned in the 18th century, about 1720 or a few years later.[30]

From 1599 to 1756, Samarkand was ruled by the Ashtrakhanid branch of the Khanate of Bukhara.

From 1756 to 1868, Samarkand was ruled by the Manghud (Mongol) Emirs of Bukhara.[31]

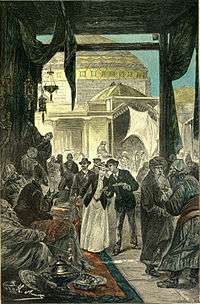

Russian Tzarist and Soviet rule

The city came under imperial Russian rule after the citadel had been taken by a force under Colonel Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman in 1868. Shortly thereafter the small Russian garrison of 500 men were themselves besieged. The assault, which was led by Abdul Malik Tura, the rebellious elder son of the Bukharan Emir, as well as Baba Beg of Shahrisabz and Jura Beg of Kitab, was repelled with heavy losses. Alexander Abramov became the first Governor of the Military Okrug, which the Russians established along the course of the Zeravshan River, with Samarkand as the administrative centre. The Russian section of the city was built after this point, largely to the west of the old city.

In 1886, the city became the capital of the newly formed Samarkand Oblast of Russian Turkestan and grew in importance still further when the Trans-Caspian railway reached the city in 1888.

It became the capital of the Uzbek SSR in 1925, before being replaced by Tashkent in 1930. During World War II, after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, a number of citizens of Samarqand were sent to the land of Smolensk, to fight the enemy. Many were taken captive or killed by the Nazis.[32][33]

Geography

Samarkand is located in north-eastern Uzbekistan, in the Zarefshan River valley. Qarshi is located 135 km away. Road M37 connects it to Bukhara, 240 km away. Road M39 connects it to Tashkent, 270 km away. The Tajikistan border is about 35 km from Samarkand, the road leading to Dushanbe which is 210 km away. Road M39 connects it to Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, which is 340 km away.

Climate

Samarkand features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa) that closely borders on a semi-arid climate (BSk) with hot, dry summers and relatively wet, variable winters that alternate periods of warm weather with periods of cold weather. July and August are the hottest months of the year with temperatures reaching, and exceeding, 40 °C (104 °F). Most of the sparse precipitation is received from December through April. January 2008 was particularly cold, and the temperature dropped to −22 °C (−8 °F)[34]

| Climate data for Samarkand (1981–2010, extremes 1936–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

41.4 (106.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−22 (−8) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.2 (1.62) |

46.2 (1.82) |

68.8 (2.71) |

60.5 (2.38) |

36.3 (1.43) |

6.1 (0.24) |

3.7 (0.15) |

1.2 (0.05) |

3.5 (0.14) |

16.8 (0.66) |

33.9 (1.33) |

47.0 (1.85) |

365.2 (14.38) |

| Average precipitation days | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 101 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 7 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 6 | 28 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 74 | 70 | 63 | 54 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 47 | 59 | 68 | 74 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.9 | 130.9 | 169.3 | 219.3 | 315.9 | 376.8 | 397.7 | 362.3 | 310.1 | 234.3 | 173.3 | 130.3 | 2,953.1 |

| Source #1: Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of Uzbekistan[35] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Pogoda.ru.net (mean temperatures/humidity/snow days 1981–2010, record low and record high temperatures),[36] NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[37] | |||||||||||||

People

According to official reports, a majority of the inhabitants of Samarkand are Uzbeks, who are Turkic people. However, most of the "Uzbeks" are in fact Tajiks (or Iranian people), even though their passports list their ethnicity as Uzbek. Approximately 70% of Samarkand residents are Tajik (Persian)-speaking Tajiks.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] Tajiks are especially concentrated in the east of the city, where the main architectural monuments of Samarkand are.

According to various independent sources, Tajiks are the major ethnic group in the city, while ethnic Uzbeks form a growing minority.[46] Exact figures are difficult to evaluate, since some people in Uzbekistan either identify as "Uzbek" even though they speak Tajik as their first language, or because they are registered as Uzbeks by the central government despite their Tajik language and identity. As explained by Paul Bergne:

During the census of 1926 a significant part of the Tajik population was registered as Uzbek. Thus, for example, in the 1920 census in Samarkand city the Tajiks were recorded as numbering 44,758 and the Uzbeks only 3301. According to the 1926 census, the number of Uzbeks was recorded as 43,364 and the Tajiks as only 10,716. In a series of kishlaks [villages] in the Khojand Okrug, whose population was registered as Tajik in 1920 e.g. in Asht, Kalacha, Akjar i Tajik and others, in the 1926 census they were registered as Uzbeks. Similar facts can be adduced also with regard to Ferghana, Samarkand, and especially the Bukhara oblasts.[46]

Uzbeks are in fact an ethnic minority in Samarkand, second to the Tajiks, and are most concentrated in the west of Samarkand.

Also in Samarkand there is a large diaspora of Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Armenians, Azeris, Tatars, Koreans, Poles, and Germans, all of whom live primarily in the center and in the west of Samarkand. The main language of these nationalities is Russian language. These peoples have arrived in Samarkand since the end of the 19th century, and especially in Soviet times, and have stayed here forever.

In the extreme West and Southwest of Samarkand, there is a population of Central Asian Arabs, who mostly speak Uzbek; only a small part of the older generation speaks Central Asian Arabic. Also in the East of Samarkand there is a large mahalla of Bukharian (Central Asian) Jews, where only a few Jewish families are left today. The remaining hundreds of thousands of Jews left Uzbekistan starting in the 1970s for Israel, United States, Canada, Australia and Europe.

Also in the eastern part of Samarkand there are several quarters, where Central Asian Gypsies (Luli, Djugi, Mugat, Parya and other groups) live, hailing from the modern territories of India and Pakistan, who began to arrive in Samarkand several centuries ago. They mainly speak a special dialect of the Tajik language, as well as their own languages (the Parya language is most known).

Language

The state and official language in Samarkand, as in all Uzbekistan, is Uzbek language, which is one of the Turkic languages. 95% of signs and inscriptions in the city in Uzbek language (mostly in Uzbek Latin alphabet). Officially, it is believed that the most common language in Samarkand is Uzbek, but in fact, according to some data, this language is native to about 30% of the residents of Samarkand. The other inhabitants of Samarkand speak the Uzbek language as the second language. There is no accurate data on this, since there has been no population census in Uzbekistan since 1989. Uzbek language is the mother tongue of Uzbeks, Turkmens, Samarkandian Iranians, and most Samarkandian Arabs who live in Samarkand.

As in the rest of Uzbekistan, Russian language is de facto the second official language in Samarkand, and about 5% of signs and inscriptions in Samarkand are in this language. Russians, Belarusians, Poles, Germans, Koreans, the majority of Ukrainians, the majority of Armenians, Greeks, part of Tatars and part of Azerbaijanis speak Russian in Samarkand. Several newspapers in Russian are published in Samarkand, the most popular of which is "Samarkandskiy vestnik" (Russian: Самаркандский вестник — Samarkand Herald), Samarkandian TV channel STV partially broadcasts in Russian language.

De facto, the most common native language in Samarkand is Tajik language (Tajiki), which is one of the dialects or variants of the Persian language (Farsi). Samarkand was one of those cities where Persian language developed. Here, at various times, many Persian classical poets and writers lived or visited, the most famous Abulqasem Ferdowsi, Omar Khayyam, Abdurahman Jami, Abu Abdullah Rudaki, Suzani Samarqandi, Kamal Khujandi and others.

According to some, the native language of about 70% of the inhabitants of Samarkand is Tajik language. These about 70% speak Uzbek as a second language, and Russian as a third language. Despite the fact that Tajik language is actually one of the two (with Uzbek language) most common languages in Samarkand, this language has no status of an official or regional language.[38][39][40][41][43][44][45][47] In the city of Samarkand only one newspaper is published in Tajik language (in Cyrllic Tajik alphabet), which is called "Ovozi Samarqand" (Tajik: Овози Самарқанд — Voice of Samarkand). Local Samarkandian STV and "Samarqand" TV channels also broadcast partially in Tajik language, also a regional radio station partly broadcasts in Tajik language

In addition to Uzbek, Tajik and Russian languages, for some residents of Samarkand, the native language is Ukrainian (for some Ukrainians), Armenian, Azerbaijani, Tatar, Crimean Tatar, Arabic (for a very small percentage of Samarkandian Arabs), and other languages.

Religion

Islam

Islam entered Samarkand in the 8th century, during the invasion of the Arabs in Central Asia (Umayyad Caliphate). Before that, almost all the inhabitants of Samarqand were Zoroastrians, many Nestorians and Buddhists also lived in the city.

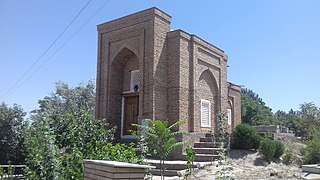

Starting from the 8th century, Muslim mosques, madrasahs and minarets began to be built in Samarkand, in the era of the entry of Samarqand into the states of Abbasid Caliphate, Samanid Empire, Kraakhanid Khanate, Khwarazm Empire, Timurid Empire, Khanate of Bukhara and Emirate of Bukhara. Until today, many ancient Muslim mosques, madrasas, minarets and mausoleums have been preserved in Samarqand. In Samarqand is the shrine of Imam Bukhari. He Islamic scholar, authored the hadith collection known as Sahih al-Bukhari, regarded by Sunni Muslims as one of the most authentic (sahih) hadith collections. He also wrote other books such as Al-Adab al-Mufrad. Also in Samarqand is the shrine of Imam Maturidi, the founder of Maturidism. Also in Samarqand is the mausoleum of the prophet Daniel, which is revered in Islam, Judaism and Christianity.

Most of the inhabitants of Samarqand are Muslims, mostly Sunni (mostly Hanafi) and Sufism. Sunnis are almost all Tajiks, Uzbeks and Samarqandian Arabs living in Samarkand. Approximately 80-85% of Samarqand Muslims are Sunni. There are also a lot of Atheists among those peoples in Samarqand, as well as those who have converted to other religions. Also a lot of very secular people.

Shia Muslims

According to some data, about 1 million people in the Samarqand Vilayat are Shiites (mostly Shia Twelvers). The population of the Samarqand Vilayat is more than 3,720,000 people (2019). There are no exact data on the number of Shiites in the city of Samarqand. Samarqand Vilayat is one of the two regions of Uzbekistan (along with Bukhara Vilayat), where a large number of Shiites live. In other regions of Uzbekistan there are few Shiites. In Samarqand, there are several Shiite mosques and madrasas. For example, the largest of them are the Punjabi Mosque and the Punjabi Madrassah, the Mausoleum of Mourad Avliya. Every year, Shiites of Samarkand celebrate Ashura, as well as other memorable dates and holidays of Shiites. The total number of followers of Shiism in Uzbekistan is not officially announced, but is estimated at "several hundred thousand." According to WikiLeaks, in 2007–2008, the US Ambassador for International Religious Freedom held a series of meetings with Sunni mullahs and Shiite imams in Uzbekistan. During one of the talks, the Imam of the Shiite mosque in Bukhara said that about 300 thousand Shiites live in the Bukhara Vliayat and another million in the Samarqand Vilayat. The Ambassador slightly doubted the authenticity of these figures, emphasizing in his report that the data on the number of religious and ethnic minorities by the government of Uzbekistan are considered to be a very "delicate topic" in order not to provoke interethnic and inter-religious contradictions. All the ambassadors of the ambassador tried to emphasize that traditional Islam, especially Sufism and Sunnism in the regions of Bukhara and Samarqand, is characterized by great religious tolerance and tolerance towards other religious movements, including Shiites[48][49][50]

Shiites in Samarqand are mostly Samarqandian Iranians, who call themselves Irani. Most Iranians began to move to Samarqand since the 18th century. Some of them arrived in Samarqand in search of a better life, some were forcibly brought in by the Turkmens who had stolen them, who sold them in Samarqand as slaves, some arrived in the army as soldiers, and remained to live in Samarqand. Mostly they came from Khorasan, Mashhad, Sabzevar, Nishapur, Merv, and also from Iranian Azerbaijan, Zanjan, Tabriz, Ardabil. Shiites are also Azerbaijanis and some Tajiks living in Samarkand. Also Shiites in Samarkand are local Azerbaijanis, as well as a small part of Tajiks and Uzbeks.

Christianity

History

Christianity was introduced in Samarkand during the existence of the Soghdiana. At that time, Samarkand became one of the centers of Nestorianism in Central Asia.[51] Several Nestorian temples were built, which have not survived to this day. The remains of these temples were found by archeologists in the ancient site Afrasiyab and on the outskirts of Samarkand. At that time, the majority of the population of Samarkand were Zoroastrians, but since Samarkand was the crossroads of caravans between China, Persia and Europe, this city was religiously tolerant. Thus, Christianity appeared in Samarkand long before the penetration of Islam into Central Asia. After the penetration of Islam into Central Asia (Umayyad Caliphate), the Zoroastrians and Nestorians were destroyed by the Arab conquerors, the rest fled to other places, or converted to Islam.

In 1329-1359 the Samarkand eparchy of the Roman Catholic Church existed in Samarkand, and several thousand Catholics lived in the city. According to Marco Polo and Johann Elemosina, a descendant of Chaghatai Khan, the founder of the Chaghatai dynasty, Eljigidey converted to Christianity and was baptized. With the assistance of Eljigidey, the Catholic Church of St. John the Baptist was built in Samarkand. After a while Islam completely supplanted Catholicism.

Christianity reappeared in Samarkand several centuries later, from the mid-19th century. Orthodoxy appeared in Samarkand in 1868, after the seizure of Samarkand by the Russian Empire. In the late 19th century, several churches and temples were built, in the early 20th century, several more Orthodox cathedrals, churches and temples were built, most of which were demolished during the USSR.

Now

The second largest religious group in Samarkand after Islam is Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). More than about 5% of the residents of Samarkand are Orthodox, among them mostly Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians, and also partly Koreans and Greeks of Samarkand. Samarkand is the center of the Samarkand branch (includes Samarkand, Qashqadarya and Surkhandarya provinces of Uzbekistan) of the Uzbekistan and Tashkent eparchy of the Central Asian Metropolitan District of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The city has several active Orthodox churches: Cathedral of St. Alexiy Moscowskiy, Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin, Church of St. George the Victorious, as well as a number of inactive Orthodox churches and temples, for example Church of St. George Pobedonosets.[52][53]

There are also many Catholics in Samarkand, mostly Poles, Germans and some Ukrainians of Samarkand. Catholics are a few tens of thousands of Samarkandians. In the center of Samarkand is the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, which is built at the beginning of the last century. Samarkand is part of Apostolic Administration of Uzbekistan.[54]

The third largest Christian movement in Samarkand is the Armenian Apostolic Church. In the west of Samarkand is the Armenian Church Surb Astvatsatsin.[55] The followers of the Armenian Church are a few tens of thousands of Samarkandian Armenians. Armenian Christians appeared in Samarkand since the end of the 19th century, and their flow to Samarkand increased especially in Soviet times.[56]

- St. John the Baptist Catholic Church

In Samarkand also has several thousand Protestantism followers, and also Lutherans, Baptists, Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, Adventists, Korean Presbyterian church. These Christian movements appeared in Samarkand mainly after the independence of Uzbekistan in 1991.[57]

Main sights

Ensembles

Registan Ensemble and Square

Registan Ensemble and Square Shahi Zinda Ensemble

Shahi Zinda Ensemble

Mausoleums and shrines

Mausoleums

Gure Amir (Shrine of Timur and Timurids)

Gure Amir (Shrine of Timur and Timurids)

Holy shrines and mausoleums

Other Complexes

- Chorsu

- Ulughbek Observatory

Madrasas

.jpg) Ulughbek Madrasa

Ulughbek Madrasa

Mosques

- Bibi Khanum Mosque

_(6009412301).jpg)

Architecture

Timur initiated the building of Bibi Khanum after his campaign in India in 1398–1399. Before its reconstruction after an earthquake in 1897, Bibi Khanum had around 450 marble columns that were established with the help of 95 elephants that Timur had brought back from Hindustan. Also from India, artisans and stonemasons designed the mosque's dome, giving it its distinctiveness amongst the other buildings.[23]

The best-known structure in Samarkand is the mausoleum known as Gur-i Amir. It exhibits many cultures and influences from past civilizations, neighboring peoples, and especially those of Islam. Despite how much devastation the Mongols caused in the past to all of the Islamic architecture that had existed in the city prior to Timur's succession, much of the destroyed Islamic influences were revived, recreated, and restored under Timur. The blueprint and layout of the mosque itself follows the Islamic passion of geometry and other elements of the structure had been precisely measured. The entrance to the Gur-i Amir is decorated with Arabic calligraphy and inscriptions, the latter being a common feature in Islamic architecture. The attention to detail and meticulous nature of Timur is especially obvious when looking inside the building. Inside, the walls have been covered in tiles through a technique, originally developed in Iran, called "mosaic faience," a process where each tile is cut, colored, and fit into place individually.[23] The tiles were also arranged in a specific way that would engrave words relating to the city's religiosity; words like "Muhammad" and "Allah" have been spelled out on the walls using the tiles.[23]

The ornaments and decorations of the walls include floral and vegetal symbols which are used to signify gardens. Gardens are commonly interpreted as paradise in the Islamic religion and they were both inscribed in tomb walls and grown in the city itself.[23] In the city of Samarkand, there were two major gardens, the New Garden and the Garden of Heart's Delight, and these became the central areas of entertainment for ambassadors and important guests. A friend of Genghis Khan in 1218 named Yelü Chucai, reported that Samarkand was the most beautiful city of all where "it was surrounded by numerous gardens. Every household had a garden, and all the gardens were well designed, with canals and water fountains that supplied water to round or square-shaped ponds. The landscape included rows of willows and cypress trees, and peach and plum orchards were shoulder to shoulder."[58] The floors of the mausoleum are entirely covered with uninterrupted patterns of tiles of flowers, emphasizing the presence of Islam and Islamic art in the city. In addition, Persian carpets with floral printings have been found in some of the Timurid buildings.[59]

Turko-Mongol influence is also apparent in the architecture of the buildings in Samarkand. For instance, nomads previously used yurts, traditional Mongol tents, to display the bodies of the dead before they were to engage in proper burial procedures. Similarly, it is believed that the melon-shaped domes of the tomb chambers are imitations of those yurts. Timur naturally used stronger materials, like bricks and wood, to establish these tents, but their purposes remain largely unchanged.[23]

The elements of traditional Islamic architecture can be seen in traditional Uzbek houses that are built around central courtyards with gardens.[60] The houses are built from mud brick and most have painted wooden ceilings and wall decorations. Houses in the west of the city are indicative of European style homes built in 19th and 20th centuries.[60]

The color of the buildings in Samarkand also has significant meaning behind it. For instance, blue is the most common and dominant color that will be found on the buildings, which was used by Timur in order to symbolize a large range of ideas. For one, the blue shades seen in the Gur-i Amir are colors of mourning. Blue was the color of mourning in Central Asia at the time, as it is in many cultures even today, so its dominance in the city's mausoleum appears only logical. In addition, blue was also seen as the color that would ward off "the evil eye" in Central Asia and the notion is evident in the number of doors in and around the city that were colored blue during this time. Furthermore, blue was representative of water, which was a particularly rare resource around the Middle East and Central Asia; coloring the walls blue symbolized the wealth of the city.

Gold also has a strong presence in the city. Timur's fascination with vaulting explains the excessive use of gold in the Gur-i Amir as well as the use of embroidered gold fabric in both the city and his buildings. The Mongols had great interests in Chinese- and Persian-style golden silk textiles as well as nasij woven in Iran and Transoxiana. Past Mongol leaders, like Ogodei, built textile workshops in their cities in order to be able to produce gold fabrics themselves.

There is evidence that Timur tried to preserve his Mongol roots. In the chamber in which his body was laid, "tuqs" were found – those are poles with horses' tails hanging at the top, which was symbolic of an ancient Turkic tradition where horses, which were valuable commodities, were sacrificed in order to honor the dead,[23] and a cavalry standard type shared by many nomads, up to the Ottoman Turks.

Transport

Public transport is developed in Samarkand. Municipal bus (mostly SamAuto and Isuzu buses) is the most common and popular transport in the city. Also in the city since 2017 there are several Samarkandian tram lines (tram existed in Samarkand also in 1947-1973), mostly Vario LF.S Czech trams. Also, the city very much a city taxi (mostly Chevrolet and Daewoo sedans), which is usually yellow in color. Also in the city a lot of taxis, which are usually yellow. Also in the city run the so-called "Marshrutka", which are minibuses Daewoo Damas and GAZelle.

Many yellow taxis on the streets of Samarkand

Many yellow taxis on the streets of Samarkand Taxi and tram on Rudaki Street in Samarkand

Taxi and tram on Rudaki Street in Samarkand Tram in Samarkand

Tram in Samarkand Beruni and Rudaki Streets in Samarkand

Beruni and Rudaki Streets in Samarkand Taxi and bus on Mirzo Ulughbek Avenue in Samarkand

Taxi and bus on Mirzo Ulughbek Avenue in Samarkand

In Soviet times, up until 2005, in Samarkand plied also to the trolleybus. In Soviet times, as well as today, municipal buses and taxis (GAZ-21, GAZ-24, GAZ-3102, VAZ-2101, VAZ-2106 and VAZ-2107) operated in Samarkand. Tram existed in Samarkand also in 1947–1973, and in 1924-1930 there was a steam tram in Samarkand. Until 1950, the main transport in Samarkand were the carriages and "arabas" with horses and donkeys.

"Araba" and donkey in Samarkand in 1890

"Araba" and donkey in Samarkand in 1890 Samarkand railway station in 1890

Samarkand railway station in 1890 "Araba" in Samarkand in 1964

"Araba" in Samarkand in 1964 "Araba" in Samarkand in 1964

"Araba" in Samarkand in 1964

In the North of Samarkand is the Samarkand International Airport, which was opened in Soviet times, in the 1930s. As of spring 2019, Samarkand International Airport has flights to Tashkent, Nukus, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Istanbul and Dushanbe, and also makes Charter flights to other cities.

Today Samarkand is an important railway center of Uzbekistan. All trains running from East to West of Uzbekistan and back pass through Samarkand. The most important and longest national railway route is Tashkent-Kungrad, which passes through Samarkand. High-speed Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) trains run between Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara. Samarkand also has an international railway connection Saratov-Samarkand, Moscow-Samarkand, Nur-Sultan-Samarkand.

Samarkand railway station

Samarkand railway station_(3).jpg) Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train in Samarkand railway station

Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train in Samarkand railway station.jpg) In Samarkand railway station

In Samarkand railway station Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train

Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train

Railway transport reached Samarkand in 1888 as a result of the construction of the Trans-Caspian railway in 1880-1891 by the railway troops of the Russian Empire on the territory of modern Turkmenistan and the Central part of modern Uzbekistan. This railway started from Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) on the Caspian Sea coast and ended at the station of Samarkand. It was Samarkand station that was the final station of the Trans-Caspian railway. The first station of Samarkand station was opened in May 1888.

Later, due to the construction of the railway in other parts of Central Asia, the station was connected to the Eastern part of the railway of Central Asia and later this railway was called Central Asian Railways. In the Soviet years in Samarkand was annexed, no new line but at the same time, it was one of the largest and most important stations of the Uzbekistan SSR and Soviet Central Asia.

Notable locals

.jpg)

- Ancient and feudal eras

- Amoghavajra, 8th-century Buddhist monk, a founder of Chinese esoteric Buddhism.

- Abu Mansur Maturidi, Sunni theologist of the 10th century

- Nizami Aruzi Samarqandi, Persian poet and writer of the 12th century

- Suzani Samarqandi, Persian poet of the 12th century

- Fatima bint Mohammed ibn Ahmad Al Samarqandi, a 12th-century ulema (Islamic scholar)

- Najib ad-Din-e-Samarqandi, scholar of the 13th century

- Jamshīd al-Kāshī, astronomer and mathematician of the 15th century

- Shams al-Dīn al-Samarqandī, scholar

- Nawab Khwaja Abid Siddiqi, general for the Mughal Empire, grandfather of Qamar-ud-din Khan, Asif Jah I

- Ibrahim Asmarakandi, 14th century proselytizer who introduced Islam to Java

- modern era

- Islam Karimov, first president of Uzbekistan

- Lev Leviev (born 1956), Israeli billionaire businessman, philanthropist, and investor

- Irina Viner head coach of the Russian rhythmic gymnastics federation

- Vladimir Vapnik professor of computer science and statistics, co-inventor of SVM method in machine learning

- Allama Makhdoom Aalam Samarqandi

- Zarrukh Adashev, professional kickboxer and mixed martial artist

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Photo gallery

See also

- Samarkand Airport

References

- Guidebook of history of Samarkand", ISBN 978-9943-01-139-7

- "History of Samarkand". Sezamtravel. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "Uzbekistan: Provinces, Major Cities & Towns – Statistics & Maps on City Population". Citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Энциклопедия туризма Кирилла и Мефодия. 2008.

- "History of Samarkand". www.advantour.com. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites (2nd ed.). London: McFarland. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

Samarkand City, southeastern Uzbekistan. The city here was already named Marakanda, when captured by Alexander the Great in 329 BC. Its own name derives from the Sogdian words samar, "stone, rock", and kand, "fort, town".

- Vladimir Babak, Demian Vaisman, Aryeh Wasserman, Political organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: sources and documents, p.374

- Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972 reprint) p. 1657

- Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. London.

- Shichkina, G.V. (1994). "Ancient Samarkand: capital of Soghd". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 83.

- Shichkina, G.V. (1994). "Ancient Samarkand: capital of Soghd". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 86.

- Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California. p. 319.

- Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California.

- Wellhausen, J. (1927). Weir, Margaret Graham (ed.). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. University of Calcutta. pp. 437–438.

- Whitfield, Susan (1999). Life Along the Silk Road. California: University of California Press. p. 33.

- Quraishi, Silim "A survey of the development of papermaking in Islamic Countries", Bookbinder, 1989 (3): 29–36.

- Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California. p. 320.

- Jacques Gernet (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- E.J.W. Gibb memorial series. 1928. p. 451.

- E. Bretschneider (1888). "The Travels of Ch'ang Ch'un to the West, 1220–1223 recorded by his disciple Li Chi Ch'ang". Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. Barnes & Noble. pp. 37–108.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 143. ISBN 9780330418799.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed, p. 204

- Marefat, Roya (Summer 1992). "The Heavenly City of Samarkand". The Wilson Quarterly. 16 (3): 33–38. JSTOR 40258334.

- Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Roads: two thousand ears in the heart of Asia. Berkeley. pp. 136–7.

- Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer, p. 1657

- Le Strange, Guy (trans) (1928). Clavijo: Embassy to Tamburlaine 1403–1406. London. p. 280.

- "Samarqand". Raw W Travels. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-07-02. Retrieved 2017-10-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Samarkand, Uzbekistan". Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Britannica. 15th Ed, p. 204

- Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer. p. 1657

- "Soviet Field of Glory" (in Russian)

- Rustam Qobil (2017-05-09). "Why were 101 Uzbeks killed in the Netherlands in 1942?". BBC. Retrieved 2017-05-09.

- Samarkand.info. "Weather in Samarkand". Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- "Average monthly data about air temperature and precipitation in 13 regional centers of the Republic of Uzbekistan over period from 1981 to 2010". Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of the Republic of Uzbekistan (Uzhydromet). Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- "Weather and Climate-The Climate of Samarkand" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- "Samarkand Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Richard Foltz (1996). "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan". Central Asian Survey. 15 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1080/02634939608400946.

- Karl Cordell, "Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe", Routledge, 1998. p. 201: "Consequently, the number of citizens who regard themselves as Tajiks is difficult to determine. Tajikis within and outside of the republic, Samarkand State University (SamGU) academic and international commentators suggest that there may be between six and seven million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30% of the republic's 22 million population, rather than the official figure of 4.7%(Foltz 1996;213; Carlisle 1995:88).

- Lena Jonson (1976) "Tajikistan in the New Central Asia", I.B.Tauris, p. 108: "According to official Uzbek statistics there are slightly over 1 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan or about 3% of the population. The unofficial figure is over 6 million Tajiks. They are concentrated in the Sukhandarya, Samarqand and Bukhara regions."

- Richard Foltz. A History of the Tajiks. Iranians of the East. London: I.B. Tauris, 2019

- "Таджики в Узбекистане: два мнения". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Узбекистан: Таджикский язык подавляется". catoday.org — ИА "Озодагон". Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Статус таджикского языка в Узбекистане". Лингвомания.info — lingvomania.info. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Таджики – иранцы Востока? Рецензия книги от Камолиддина Абдуллаева". «ASIA-Plus» Media Group / Tajikistan — news.tj. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Paul Bergne: The Birth of Tajikistan. National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. International Library of Central Asia Studies. I.B. Tauris. 2007. Pg. 106

- "Есть ли шансы на выживание таджикского языка в Узбекистане — эксперты". "Биржевой лидер" — pfori-forex.org. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Шииты в Узбекистане". www.islamsng.com. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Ташкент озабочен делами шиитов". www.dn.kz. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Узбекистан: Иранцы-шииты сталкиваются c проблемами с правоохранительными органами". catoday.org. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Dickens, Mark "Nestorian Christianity in Central Asia. p. 17

- В. А. Нильсен. У истоков современного градостроительства Узбекистана (ΧΙΧ — начало ΧΧ веков). —Ташкент: Издательство литературы и искусства имени Гафура Гуляма, 1988. 208 с.

- Голенберг В. А. «Старинные храмы туркестанского края». Ташкент 2011 год

- Католичество в Узбекистане. Ташкент, 1990.

- Назарьян Р.Г. Армяне Самарканда. Москва. 2007

- Armenians. Ethnic atlas of Uzbekistan, 2000.

- Бабина Ю. Ё. Новые христианские течения и страны мира. Фолкв, 1995.

- Liu, Xinru (2010). The Silk Road in world history. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516174-8.

- Cohn-Wiener, Ernst (June 1935). "An Unknown Timurid Building". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 66 (387): 272–273+277. JSTOR 866154.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

Bibliography

- Alexander Morrison, Russian Rule in Samarkand 1868–1910: A Comparison with British India (Oxford, OUP, 2008) (Oxford Historical Monographs).

- Azim Malikov, Cult of saints and shrines in the Samarqand province of Uzbekistan in International journal of modern anthropology. No.4. 2010, pp. 116–123

- Azim Malikov, The politics of memory in Samarkand in post-Soviet period // International Journal of Modern Anthropology. (2018) Vol: 2, Issue No: 11, pp: 127 – 145

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samarkand. |

- Forbes, Andrew, & Henley, David: Timur's Legacy: The Architecture of Bukhara and Samarkand (CPA Media).

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Samarkand. |

- Samarkand – Silk Road Seattle Project, University of Washington

- The history of Samarkand, according to Columbia University's Encyclopædia Iranica

- Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- GCatholic – former Latin Catholic bishopric

- Samarkand: Photos, History, Sights, Useful information for travelers

- About Samarkand in Uzbekistan Latest

- Tilla-Kori Madrasa was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List

| Preceded by Gurganj |

Capital of Khwarazmian Empire 1212–1220 |

Succeeded by Ghazna |

| Preceded by Tabriz |

Capital of Iran (Persia) 1370–1501 |

Succeeded by Tabriz |

| Preceded by - |

Capital of Timurid dynasty 1370–1505 |

Succeeded by Herat |

.jpg)