World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area, selected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for having cultural, historical, scientific or other form of significance, which is legally protected by international treaties. The sites are judged to be important for the collective and preservative interests of humanity.

To be selected, a World Heritage Site must be an already-classified landmark, unique in some respect as a geographically and historically identifiable place having special cultural or physical significance (such as an ancient ruin or historical structure, building, city, complex, desert, forest, island, lake, monument, mountain, or wilderness area[1][2]). It may signify a remarkable accomplishment of humanity, and serve as evidence of our intellectual history on the planet.[3]

The sites are intended for practical conservation for posterity, which otherwise would be subject to risk from human or animal trespassing, unmonitored/uncontrolled/unrestricted access, or threat from local administrative negligence. Sites are demarcated by UNESCO as protected zones.[4] The list is maintained by the international World Heritage Program administered by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, composed of 21 "states parties" that are elected by their General Assembly.[5]

The programme catalogues, names, and conserves sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common culture and heritage of humanity. Under certain conditions, listed sites can obtain funds from the World Heritage Fund. The programme began with the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage,[6] which was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO on 16 November 1972. Since then, 193 state parties have ratified the convention, making it one of the most widely recognised international agreements and the world's most popular cultural programme.

In 1978 the city of Quito in Ecuador earned the distinction of being the first city in the world to be declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In the same year, Kraków in Poland was also named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[7][8]

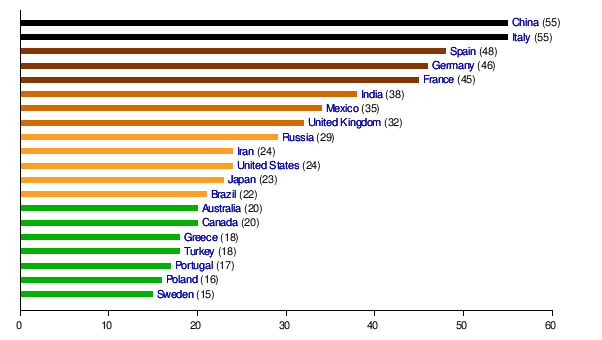

As of July 2019, a total of 1,121 World Heritage Sites (869 cultural, 213 natural, and 39 mixed properties) exist across 167 countries. China and Italy, both with 55 sites, have the most of any country, followed by Spain (48), Germany (46), France (45), India (38), and Mexico (35).[9]

History

| Signed | 16 November 1972 |

|---|---|

| Location | Paris, France |

| Effective | 17 December 1975 |

| Condition | 20 ratifications |

| Ratifiers | 193 (189 UN member states plus the Cook Islands, the Holy See, Niue, and Palestine) |

| Depositary | Director-General of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| Languages | Arabic, English, French, Russian, and Spanish |

In 1954, the government of Egypt decided to build the new Aswan High Dam, whose resulting future reservoir would eventually inundate a large stretch of the Nile valley containing cultural treasures of ancient Egypt and ancient Nubia. In 1959, the governments of Egypt and Sudan requested UNESCO to assist their countries to protect and rescue the endangered monuments and sites. In 1960, the Director-General of UNESCO launched an appeal to the member states for an International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia.[10] This appeal resulted in the excavation and recording of hundreds of sites, the recovery of thousands of objects, as well as the salvage and relocation to higher ground of a number of important temples, the most famous of which are the temple complexes of Abu Simbel and Philae. The campaign, which ended in 1980, was considered a success. As tokens of its gratitude to countries which especially contributed to the campaign's success, Egypt donated four temples: the Temple of Dendur was moved to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Temple of Debod was moved to the Parque del Oeste in Madrid, the Temple of Taffeh was moved to the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in the Netherlands, and the Temple of Ellesyia to Museo Egizio in Turin.[11]

The project cost $80 million, about $40 million of which was collected from 50 countries.[12] The project's success led to other safeguarding campaigns: saving Venice and its lagoon in Italy, the ruins of Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan, and the Borobodur Temple Compounds in Indonesia. UNESCO then initiated, with the International Council on Monuments and Sites, a draft convention to protect cultural heritage.[12]

Convention and background

The United States initiated the idea of cultural conservation with nature conservation. The White House conference in 1965 called for a "World Heritage Trust" to preserve "the world's superb natural and scenic areas and historic sites for the present and the future of the entire world citizenry". The International Union for Conservation of Nature developed similar proposals in 1968, and they were presented in 1972 to the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. Under the World Heritage Committee, signatory countries are required to produce and submit periodic data reporting providing the World Heritage Committee with an overview of each participating nation's implementation of the World Heritage Convention and a "snapshot" of current conditions at World Heritage properties.

Based on the draft convention that UNESCO had initiated, a single text was eventually agreed on by all parties, and the "Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage" was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO on 16 November 1972.[13]

The Convention came into force on 17 December 1975. As of May 2017, it has been ratified by 193 states parties,[14] including 189 UN member states plus 2 UN observer states (the Holy See and the State of Palestine) and 2 states in free association with New Zealand (the Cook Islands and Niue). Only four UN member states have not ratified the Convention: Liechtenstein, Nauru, Somalia and Tuvalu.[15]

The protection of the world heritage should also preserve the particularly sensitive cultural memory, the growing cultural diversity and the economic basis of a state, a municipality or a region. Whereby there is also a connection between cultural user disruption or world heritage and the cause of flight, as President of Blue Shield International Karl von Habsburg-Lorraine explained during an United Nations peacekeeping and UNESCO mission in Lebanon in April 2019: “Cultural assets are part of the identity of the people who live in a certain place. If you destroy their culture, you also destroy their identity. Many people are uprooted, often have no prospects anymore and subsequently flee from their homeland ”.[16][17][18]

Nomination process

A country must first list its significant cultural and natural sites; the result is called the Tentative List. A country may not nominate sites that have not been first included on the Tentative List. Next, it can place sites selected from that list into a Nomination File.

The Nomination File is evaluated by the International Council on Monuments and Sites and the World Conservation Union. These bodies then make their recommendations to the World Heritage Committee. The Committee meets once per year to determine whether or not to inscribe each nominated property on the World Heritage List and sometimes defers or refers the decision to request more information from the country which nominated the site. There are ten selection criteria – a site must meet at least one of them to be included on the list.[19]

Selection criteria

Up to 2004, there were six criteria for cultural heritage and four criteria for natural heritage. In 2005, this was modified so that there is now only one set of ten criteria. Nominated sites must be of "outstanding universal value" and meet at least one of the ten criteria.[20] These criteria have been modified or/amended several times since their creation.

Cultural

- "represents a masterpiece of human creative genius and cultural significance"

- "exhibits an important interchange of human values, over a span of time, or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning, or landscape design"

- "to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared"

- "is an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural, or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates a significant stage in human history"

- "is an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of a culture, or human interaction with the environment especially when it has become vulnerable under the impact of irreversible change"

- "is directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance" [21]

Natural

- "contains superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and esthetic importance"

- "is an outstanding example representing major stages of Earth's history, including the record of life, significant on-going geological processes in the development of landforms, or significant geomorphic or physiographic features"

- "is an outstanding example representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems, and communities of plants and animals"

- "contains the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation"

Extensions and other modifications

A country may request to extend or reduce the boundaries, modify the official name, or change the selection criteria of one of its already listed sites. Any proposal for a significant boundary change or to modify the site's selection criteria must be submitted as if it were a new nomination, including first placing it on the Tentative List and then onto the Nomination File.[19]

A request for a minor boundary change, one that does not have a significant impact on the extent of the property or affect its "outstanding universal value", is also evaluated by the advisory bodies before being sent to the Committee. Such proposals can be rejected by either the advisory bodies or the Committee if they judge it to be a significant change instead of a minor one.[19]

Proposals to change a site's official name are sent directly to the Committee.[19]

Endangerment

A site may be added to the List of World Heritage in Danger if there are conditions that threaten the characteristics for which the landmark or area was inscribed on the World Heritage List. Such problems may involve armed conflict and war, natural disasters, pollution, poaching, or uncontrolled urbanization or human development. This danger list is intended to increase international awareness of the threats and to encourage counteractive measures. Threats to a site can be either proven imminent threats or potential dangers that could have adverse effects on a site.[22]

The state of conservation for each site on the danger list is reviewed on a yearly basis, after which the committee may request additional measures, delete the property from the list if the threats have ceased or consider deletion from both the List of World Heritage in Danger and the World Heritage List.[19]

Only two sites have ever been delisted: the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary in Oman and the Dresden Elbe Valley in Germany. The Arabian Oryx Sanctuary was directly delisted in 2007, instead of first being put on the danger list, after the Omani government decided to reduce the protected area's size by 90 percent.[23] The Dresden Elbe Valley was first placed on the danger list in 2006 when the World Heritage Committee decided that plans to construct the Waldschlösschen Bridge would significantly alter the valley's landscape. In response, Dresden City Council attempted to stop the bridge's construction, but after several court decisions allowed the building of the bridge to proceed, the valley was removed from the World Heritage List in 2009.[24]

The first global assessment to quantitatively measure threats to Natural World Heritage sites found[25] that 63 percent of sites have been damaged by increasing human pressures[26] including encroaching roads, agriculture infrastructure and settlements over the last two decades. These activities endanger Natural World Heritage sites and could compromise their unique values. Of the Natural World Heritage sites that contain forest, 91 percent of those experienced some loss since the year 2000. Many Natural World Heritage sites are more threatened than previously thought and require immediate conservation action.

Furthermore, the destruction of cultural assets and identity-establishing sites is one of the primary goals of modern asymmetrical warfare. Therefore, terrorists, rebels and mercenary armies deliberately smash archaeological sites, sacred and secular monuments and loot libraries, archives and museums. The UN, United Nations peacekeeping and UNESCO and in cooperation with Blue Shield International are active in preventing such acts. "No strike lists" are also created to protect cultural assets from air strikes.[27][28][29] But only through cooperation with the locals can the protection of world heritage sites, archaeological finds, exhibits and archaeological sites from destruction, looting and robbery be implemented sustainably. The president of Blue Shield International Karl von Habsburg summed it up with the words: “Without the local community and without the local participants, that would be completely impossible”.[30][31]

Statistics

The World Heritage Committee has divided the world into five geographic zones which it calls regions: Africa, Arab states, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean.

Russia and the Caucasus states are classified as European, while Mexico and the Caribbean are classified as belonging to the Latin America and Caribbean zone. The UNESCO geographic zones also give greater emphasis on administrative, rather than geographic associations. Hence, Gough Island, located in the South Atlantic, is part of the Europe and North America region because the government of the United Kingdom nominated the site.

The table below includes a breakdown of the sites according to these zones and their classification as of July 2019:[32][33]

| Zone/region | Cultural | Natural | Mixed | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 53 | 38 | 5 | 96 | 8.56% |

| Arab states | 78 | 5 | 3 | 86 | 7.67% |

| Asia and the Pacific | 189 | 67 | 12 | 268 | 23.91% |

| Europe and North America | 453 | 65 | 11 | 529 | 47.19% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 96 | 38 | 8 | 141 | 12.58% |

| Total | 869 | 213 | 39 | 1121 | 100% |

Countries with fifteen or more sites

Countries with fifteen or more World Heritage Sites as of July 2019:

Consequences

Despite the successes of World Heritage listing in promoting conservation, the UNESCO administered project has attracted criticism from some for perceived under-representation of heritage sites outside Europe, disputed decisions on site selection and adverse impact of mass tourism on sites unable to manage rapid growth in visitor numbers.[34][35]

A sizable lobbying industry has grown around the awards because World Heritage listing has the potential to significantly increase tourism revenue from sites selected. Site listing bids are often lengthy and costly, putting poorer countries at a disadvantage. Eritrea's efforts to promote Asmara is one example.[36]

In 2016, the Australian government was reported to have successfully lobbied for Great Barrier Reef conservation efforts to be removed from a UNESCO report titled 'World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate'. The Australian government's actions were in response to their concern about the negative impact that an 'at risk' label could have on tourism revenue at a previously designated UNESCO World Heritage site.[37][38]

A number of listed World Heritage locations such as George Town, Penang, and Casco Viejo, Panama, have struggled to strike the balance between the economic benefits of catering to greatly increased visitor numbers and preserving the original culture and local communities that drew the recognition.[39]

See also

- GoUNESCO - initiative to promote awareness and provide tools for laypersons

- Index of conservation articles

- Lists of World Heritage Sites

- Memory of the World Programme - to save documentary heritage of humanity

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists

References

- Ann Marie Sullivan, Cultural Heritage & New Media: A Future for the Past, 15 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L. 604 (2016) https://repository.jmls.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1392&context=ripl

- Allan, James R.; Kormos, Cyril; Jaeger, Tilman; Venter, Oscar; Bertzky, Bastian; Shi, Yichuan; MacKey, Brendan; Van Merm, Remco; Osipova, Elena; Watson, James E.M. (2018). "Gaps and opportunities for the World Heritage Convention to contribute to global wilderness conservation". Conservation Biology. 32 (1): 116–126. doi:10.1111/cobi.12976. PMID 28664996.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Criteria for Selection". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "World Heritage". Archived from the original on 30 June 2009.

- "The World Heritage Committee". UNESCO World Heritage Site. Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- Convention Concerning the Protection of World's Cultural and Natural Heritage Archived 4 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/unesco-first-12-world-heritage-sites/index.html

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/&order=year

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Monuments of Nubia-International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine World Heritage Convention, UNESCO

- The Rescue of Nubian Monuments and Sites Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO

- "The World Heritage Convention – Brief History". Section: "Preserving cultural heritage". UNESCO. whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "The World Heritage Convention – Brief History". Section: "Linking the protection of cultural and natural heritage". UNESCO. whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "States Parties – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage: Treaty status Archived 19 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Karl von Habsburg auf Mission im Libanon" (in German).

- Jyot Hosagrahar: Culture: at the heart of SDGs. UNESCO-Kurier, April-Juni 2017.

- Rick Szostak: The Causes of Economic Growth: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009, ISBN 9783540922827.

- "The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Criteria for Selection". World Heritage. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "UNESCO World Heritage, The Criteria for Selection". Archived from the original on 12 June 2016.

- "List of World Heritage in Danger". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Oman's Arabian Oryx Sanctuary: first site ever to be deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Dresden is deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Allan, James R.; Venter, Oscar; Maxwell, Sean; Bertzky, Bastian; Jones, Kendall; Shi, Yichuan; Watson, James E.M. (2017). "Recent increases in human pressure and forest loss threaten many Natural World Heritage Sites" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 206: 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.12.011.

- Venter, Oscar; Sanderson, Eric W.; Magrach, Ainhoa; Allan, James R.; Beher, Jutta; Jones, Kendall R.; Possingham, Hugh P.; Laurance, William F.; Wood, Peter; Fekete, Balázs M.; Levy, Marc A.; Watson, James E. M. (2016). "Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation". Nature Communications. 7: 12558. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712558V. doi:10.1038/ncomms12558. PMC 4996975. PMID 27552116.

- Peter Stone: Inquiry: Monuments Men. Apollo – The International Art Magazine vom 2. Februar 2015; Mehroz Baig: When War Destroys Identity. Worldpost vom 12. Mai 2014.

- UNESCO Director-General calls for stronger cooperation for heritage protection at the Blue Shield International General Assembly. UNESCO, 13 September 2017.

- Roger O’Keefe, Camille Péron, Tofig Musayev, Gianluca Ferrari: Protection of Cultural Property. Military Manual. UNESCO, 2016.

- Action plan to preserve heritage sites during conflict - UNITED NATIONS, 12 Apr 2019

- Blue Shield mission with the UN to protect the UNESCO World Heritage Site in Lebanon (Kronen Zeitung - German)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "World Heritage List Statistics". unesco.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List". unesco.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014.

- Barron, Laignee (30 August 2017). "'Unesco-cide': does world heritage status do cities more harm than good?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Vallely, Paul (7 November 2008). "The Big Question: What is a World Heritage Site, and does the accolade make a difference?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

- "Modernist masterpieces in unlikely Asmara". The Economist. 20 July 2016. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017.

- Slezak, Michael (26 May 2016). "Australia scrubbed from UN climate change report after government intervention". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

- Hasham, Nicole (17 September 2015). "Government spent at least $400,000 lobbying against Great Barrier Reef 'danger' listing". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016.

- Maurel, Cholé. "The unintended consequences of UNESCO world heritage listing". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World Heritage Sites. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for UNESCO World Heritage List. |

| Library resources about World Heritage Site |

- UNESCO World Heritage portal – Official website (in English and French)

- The World Heritage List – Official searchable list of all Inscribed Properties

- KML file of the World Heritage List – Official KML version of the list for Google Earth and NASA Worldwind

- UNESCO Information System on the State of Conservation of World Heritage properties – Searchable online tool with over 3.400 reports on World Heritage sites

- Official overview of the World Heritage Forest Program

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage – Official 1972 Convention Text in 7 languages

- The 1972 Convention at Law-Ref.org – Fully indexed and crosslinked with other documents

- Protected Planet — View all natural world heritage sites in the World Database on Protected Areas

- World Heritage Site – Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Time magazine. The Oscars of the Environment – UNESCO World Heritage Site

- UNESCO chair in ICT to develop and promote sustainable tourism in World Heritage Sites