Richmond, Indiana

Richmond /ˈrɪtʃmənd/ is a city in east central Indiana, United States, bordering on Ohio. It is the county seat of Wayne County,[6] and in the 2010 census had a population of 36,812. Situated largely within Wayne Township, its area includes a non-contiguous portion in nearby Boston Township, where Richmond Municipal Airport is.

City of Richmond, Indiana | |

|---|---|

City | |

.jpg) Main Street in Downtown Richmond | |

Flag | |

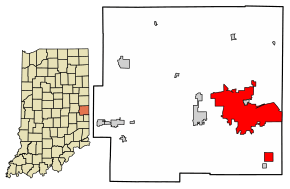

Location of Richmond in Wayne County, Indiana. | |

| Coordinates: 39°49′49″N 84°53′26″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Indiana |

| County | Wayne |

| Township | Boston, Center, Wayne |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dave Snow (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 24.16 sq mi (62.57 km2) |

| • Land | 24.00 sq mi (62.15 km2) |

| • Water | 0.16 sq mi (0.42 km2) |

| Elevation | 981 ft (299 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 36,812 |

| • Estimate (2018)[4] | 35,353 |

| • Density | 1,486.19/sq mi (573.82/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 47374-47375 |

| Area code(s) | 765 |

| FIPS code | 18-64260[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 441976 |

| Website | richmondindiana |

Richmond is sometimes called the "cradle of recorded jazz" because the earliest jazz recordings, and records were made at the studio of Gennett Records, a division of the Starr Piano Company.[7] Gennett Records was the first to record such artists as Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Jelly Roll Morton, Hoagy Carmichael, Lawrence Welk, and Gene Autry.

The city has twice received the All-America City Award, most recently in 2009.

Geography

Richmond is located at 39°49′49″N 84°53′26″W.[8]

According to the 2010 census, Richmond has a total area of 24.067 square miles (62.33 km2), of which 23.91 square miles (61.93 km2) (or 99.35%) is land and 0.157 square miles (0.41 km2) (or 0.65%) is water.[9]

Richmond is located about 12 miles S of Hoosier Hill, the highest point in Indiana.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 2,070 | — | |

| 1850 | 1,443 | −30.3% | |

| 1860 | 6,608 | 357.9% | |

| 1870 | 9,445 | 42.9% | |

| 1880 | 12,742 | 34.9% | |

| 1890 | 16,608 | 30.3% | |

| 1900 | 18,226 | 9.7% | |

| 1910 | 22,824 | 25.2% | |

| 1920 | 26,765 | 17.3% | |

| 1930 | 32,493 | 21.4% | |

| 1940 | 35,147 | 8.2% | |

| 1950 | 39,539 | 12.5% | |

| 1960 | 44,149 | 11.7% | |

| 1970 | 43,999 | −0.3% | |

| 1980 | 41,349 | −6.0% | |

| 1990 | 38,705 | −6.4% | |

| 2000 | 39,124 | 1.1% | |

| 2010 | 36,812 | −5.9% | |

| Est. 2018 | 35,353 | [4] | −4.0% |

| Source: US Census Bureau | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 36,812 people, 15,098 households, and 8,909 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,539.0 inhabitants per square mile (594.2/km2). There were 17,649 housing units at an average density of 737.8 per square mile (284.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.9% White, 8.6% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.9% from other races, and 4.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.1% of the population.

There were 15,098 households of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.5% were married couples living together, 16.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 41.0% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.91.

The median age in the city was 38.4 years. 22.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.4% were from 25 to 44; 25.6% were from 45 to 64; and 16.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.9% male and 52.1% female.

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 39,124 people, 16,287 households, and 9,918 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,685.3 people per square mile (650.8/km²). There were 17,647 housing units at an average density of 760.2 per square mile (293.6/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 86.78% White, 8.87% African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.80% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 1.09% from other races, and 2.14% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.03% of the population.

There were 16,287 households out of which 27.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.1% were married couples living together, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.1% were non-families. 33.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.89.

In the city, the population was spread out with 23.4% under the age of 18, 11.0% from 18 to 24, 27.5% from 25 to 44, 21.6% from 45 to 64, and 16.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,210, and the median income for a family was $38,346. Males had a median income of $30,849 versus $21,164 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,096. About 12.1% of families and 15.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.8% of those under age 18 and 10.8% of those age 65 or over.

History

In 1806 the first European Americans in the area, Quaker families from North Carolina, settled along the East Fork of the Whitewater River. This was part of a general westward migration in the early decades after the American Revolution. John Smith was one of the earliest settlers. Richmond is still home to several Quaker institutions, including Friends United Meeting, Earlham College and the Earlham School of Religion.

The first post office in Richmond was established in 1818 with Robert Morrison as the first postmaster.[10] The town was officially incorporated in 1840, with John Sailor elected the first mayor.[11]

Early cinema and television pioneer Charles Francis Jenkins grew up on a farm north of Richmond, where he began inventing useful gadgets. As the Richmond Telegram reported, on June 6, 1894, Jenkins gathered his family, friends and newsmen at his cousin's jewelry store in downtown Richmond and projected a filmed motion picture for the first time in front of an audience. The motion picture was of a vaudeville entertainer performing a butterfly dance, which Jenkins had filmed himself. Jenkins filed for a patent for the Phantoscope projector in November 1894 and it was issued in March 1895. A modified version of the Phantoscope was later sold to Thomas Edison, who named it Edison's Vitascope and began projecting motion pictures in New York City vaudeville theaters, raising the curtain on American cinema.

Joseph E. Maddy is credited with founding the country's first complete high school orchestra at Richmond, and later founded the National High School Orchestra Camp, which became the Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan.[12][13]

Frederick Douglass visited Richmond thrice to deliver orations. On October 5, 1843, he was pelted with “evil-smelling eggs" at an abolitionist meeting. On February 15, 1858, he spoke to an audience about “Freedom and Slavery” without incident. The third time, September 2, 1880, he spoke at both the city's railroad depot and on Main Street. He told those assembled, "When I came into your streets I was pelted with eggs by unsympathetic fellow beings. But now, how changed the scene around me! I am accepted! The shackles have been knocked off the limbs of four million human beings, and the black man and woman and child are clothed in all the rights of citizenship. I came to Richmond the first time a fleeing fugitive, chased by bloodhounds and savage men. No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck. Now I am your brother and I stand before you as a fellow citizen. Thank you."[14][15] On October 1, 1842, United States Senator Henry Clay, a slave master from Kentucky, spoke in Richmond as part of his campaign to become the presidential nominee of the Whig Party (United States). A member of the Indiana Anti-Slavery Society approached Clay with a petition demanding that he free his slaves. When the crowd grew hostile to the man, Clay said, "Oh, no, my friends. He don’t know any better. Don’t hurt him.” Clay told those assembled that "indiscriminate emancipation” would lead to "intermarriage and the possible subjugation of the whites by the blacks!"[16]

Feminist prohibitionist Carrie Nation visited Richmond several times, vociferously castigating the locals for what she viewed as their vices. She first arrived on August 15, 1902, shouting at the poorer residents, "Rum did that! It causes violence, lust and bad manners!” On September 30, 1903, she stopped long enough to address a crowd at the railroad depot, boasting that she had disrupted a poker game on the train and thrown the cards out of the window. She said she disliked Hoosiers, though her recently divorced second husband, David Nation, had been a Wayne County Civil War veteran. On July 15, 1904, Nation incited a mob and sold its members hatchets before leading them into bars, poolrooms, and a brothel, demanding that those present give up their vices. "This wicked city sweeps far and wide the juice of perversion and the billiard vice! Richmond must be converted and reclaimed!”, she declared. During Nation's fourth visit to Richmond, on July 8, 1905, she ran up and down Main Street, decrying hotels, poolrooms, bars, and grocers who sold alcohol as "Rummies! Murderers! Hellholes!” On her last visit to the city, September 22, 1908, she refused to stay at the stately Wescott Hotel because it had a bar. She directed a tirade at a local reporter, telling him, "it’s no use talking sensible to newspaper men. There’s a chance to reform everybody in the world, but not reporters! They are hopeless! They are going to singe in lakes of fire! Just wait!”[17]

In the 1920s during the national revival of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), Indiana had the largest Klan organization in the country, led by Grand Dragons D. C. Stephenson and Walter F. Bossert. At its height, national membership during the second Klan movement reached 1.5 million, with 300,000 from Indiana. Records show that Richmond (home to Whitewater Klan #60) and Wayne County were Klan strongholds, with up to 45% of the county's white men having been members. Forty percent of Richmond's Kiwanis club members, 30% of its doctors, and 27% of its lawyers were Klan members, but none of the city's bank executives or most powerful business leaders were.[18][19] In 1923 a reported 30,000 people watched a Klan parade through Richmond streets.[20][21] In 1922 Robert Lyons introduced the Klan in Richmond, initially by recruiting at Reid Memorial Presbyterian Church, where his father had been pastor.[22] The Klan polished its reputation by contributing money and goods to Protestant churches and organizations, including the Salvation Army.[23] Thomas Barr, son of Daisy Douglas Barr, prominent Quaker minister, Klan official, and first woman to serve as vice-chair of the Indiana Republican Party (United States),[24] attended Earlham College and was a KKK campus recruiter.[25][26]

Hoagy Carmichael recorded "Stardust" for the first time in Richmond at the Gennett recording studio. Famed trumpeter and singer Louis Armstrong was first recorded at Gennett as a member of King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band.[27] Many other internationally famous musicians recorded at Gennett's Richmond facility, including Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, Duke Ellington, and Fats Waller.[28] Gennett also recorded Klan musicians.[29][30]

A group of artists in the area in the late 19th and early 20th centuries came to be known as the Richmond Group. They included John Elwood Bundy, Charles Conner, George Herbert Baker, Maude Kaufman Eggemeyer and John Albert Seaford. The Richmond Art Museum has a collection of regional and American art.[31] Many consider the most significant painting in the collection to be a self-portrait of Indiana-born William Merritt Chase.[32]

The city was connected to the National Road, the first road built by the federal government and a major route west for pioneers of the 19th century.[33] It became part of the system of National Auto Trails. The highway is now known as U.S. Route 40. One of the extant Madonna of the Trail monuments was dedicated at Richmond on October 28, 1928.[34] It sits in a corner of Glen Miller Park adjacent to US 40.

Richmond's cultural resources include two of Indiana's three Egyptian mummies. One is held by the Wayne County Historical Museum and the other by Earlham College's Joseph Moore Museum, leading to the local nickname "Mummy capital of Indiana".[35][36]

The arts were supported by a strong economy increasingly based on manufacturing. Richmond was once known as "the lawnmower capital" because it was a center for manufacturing of lawnmowers from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century. Manufacturers included Davis, Motomower, Dille-McGuire and F&N. The farm machinery builder Gaar-Scott was based in Richmond. The Davis Aircraft Co.,[37][38] builder of a light parasol wing monoplane, operated in Richmond beginning in 1929.

After starting out in nearby Union City, Wayne Agricultural Works moved to Richmond. Wayne manufactured horse-drawn vehicles, including the "kid hack", a precursor of the motorized school bus. From the early 1930s through the 1940s, Richmond had several automobile designers and manufacturers. Among the automobiles locally manufactured were the Richmond, built by the Wayne Works; the "Rodefeld"; the Davis; the Pilot; the Westcott; and the Crosley.

In the 1950s Wayne Works changed its name to Wayne Corporation, by then a well-known bus and school-bus manufacturer. In 1967 it relocated to a site adjacent to Interstate 70. The company was a leader in school-bus safety innovations, but closed in 1992 during a period of school-bus manufacturing industry consolidations.[39]

Richmond was known as the "Rose City" because of the many varieties once grown there by Hill's Roses. The company had several sprawling complexes of greenhouses, with a total of about 34 acres (14 ha) under glass. The annual Richmond Rose Festival honored the rose industry and was a popular summer attraction.[40]

Downtown explosion

See: Richmond, Indiana explosion

On April 6, 1968, an explosion triggered by a natural gas leak destroyed or damaged several downtown blocks and killed 41 people; more than 150 were injured.[41] The event is documented in the book Death in a Sunny Street.

Architecture

Richmond is noted for its rich stock of historic architecture. In 2003, a book entitled Richmond Indiana: Its Physical Development and Aesthetic Heritage to 1920 by Cornell University architectural historians, Michael and Mary Raddant Tomlan, was published by the Indiana Historical Society. Particularly notable buildings are the 1902 Pennsylvania Railroad Station designed by Daniel H. Burnham of Chicago and the 1893 Wayne County Court House designed by James W. McLaughlin of Cincinnati. Local architects of note include John A. Hasecoster, William S. Kaufman and Stephen O. Yates.

The significance of the architecture has been recognized. Five large districts, such as the Depot District, and several individual buildings are listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the Historic American Buildings Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record.

Educational institutions

- Richmond has four colleges: Earlham College, Indiana University East, Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana, and the Purdue Polytechnic Institute – Richmond.

- Richmond is home to two seminaries: Earlham School of Religion (Quaker) and Bethany Theological Seminary (Church of the Brethren)

- Richmond High School includes the Richmond Art Museum and Civic Hall Performing Arts Center and the Tiernan Center, the 5th-largest high school gym in the United States.

- Seton Catholic High School (founded 2002), a junior and senior high school, is a religious high school. It is based in the former home of St. Andrew High School (1899–1936) and, more recently, St. Andrew Elementary School, adjacent to St. Andrew Church of the Richmond Catholic Community.

The Richmond Japanese Language School (リッチモンド(IN)補習授業校 Ritchimondo(IN)Hoshū Jugyō Kō) a part-time Japanese school, holds its classes at the Highland Heights School.[42][43]

The town has a lending library, the Morrisson Reeves Library.[44]

Religious groups

- Richmond is the headquarters of Friends United Meeting, and hosts the Quaker Hill Conference Center, of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers).

Transportation

Air

Richmond Municipal Airport is a public-use airport five nautical miles (6 mi, 9 km) southeast of Richmond's central business district. It is owned by the Richmond Board of Aviation Commissioners. It is also an exclave of Richmond.[45]

Richmond's closest airport with commercial service is Dayton International Airport, just under an hour's drive to the east. To the west is Indianapolis International Airport, which is slightly farther away.

Road

Richmond is served by Interstate 70 at exits 149, 151, 153, and 156. Public transit service is provided by city-owned Roseview Transit, operating daily except Sundays and major holidays.[46]

Media

The daily newspaper is the Gannett-owned Palladium-Item.

Full-power radio stations include WKBV, WFMG, WQLK, WHON, WJKL, and Earlham College's student-run public radio station WECI. Richmond is also served by WJYW which is repeated on 94.5 and 97.7. Area NPR radio stations include WBSH in Hagerstown, Indiana and WMUB in Oxford, OH.

Richmond is considered to be within the Dayton, Ohio, television market and has one full-power television station, WKOI, which is an Ion owned and operated station. The city also has one county-wide public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable television station, Whitewater Community Television.[47]

Points of interest

- Hayes Arboretum

- Wayne County Historical Museum

- Richmond Art Museum

- Indiana Football Hall of Fame

- Gaar Mansion (house museum)

- Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College

- Glen Miller Park and Madonna of the Trail statue

- Richmond Downtown Historic District

- Old Richmond Historic District

- Starr Historic District

- Richmond Railroad Station Historic District

- Reeveston Place Historic District

- East Main Street-Glen Miller Park Historic District

- Don McBride Stadium baseball ballpark built in 1936

- Reid Memorial Presbyterian Church[48] (Louis Comfort Tiffany-designed interior and windows, Hook and Hastings organ)

- Bethel AME Church (oldest AME church in Indiana: founded 1868)

- Old National Road Welcome Center (convention and tourism bureau)

- Whitewater Gorge Park and Gennett Walk of Fame

- Cardinal Greenway hiking trail

- Marceline Jones gravesite, Earlham Cemetery (Jim Jones's wife, who died in the Peoples Temple mass suicide)

- Richmond Civic Theatre (plays, classic movies, and children's theater)

- Madonna of the Trail statue at Glen Miller Park

- Gennett Records Walk of Fame

Notable people

- May Aufderheide, ragtime composer

- Bill W. Balthis (1939–2016), Illinois state representative and businessman[49]

- Christopher Benfey, literary critic

- Thomas W. Bennett (territorial governor), Richmond mayor, Governor, congressional delegate of Idaho territory,

- Landrum Bolling, president of Earlham College, humanitarian, diplomat

- Timothy Brown (actor), professional football player, television/film actor and recording-artist

- John Wilbur Chapman, evangelist

- David W. Dennis, U.S. Congressman

- George Duning, musician and composer

- Weeb Ewbank, coach of 1958 and 1959 NFL champion Baltimore Colts and the Super Bowl III champion New York Jets[50]

- Vagas Ferguson, NFL running back

- Paul Flatley, NFL wide receiver (Minnesota Vikings)

- William Dudley Foulke, lawyer, author

- Norman Foster, actor, director

- Harry "Singin' Sam" Frankel, radio star, minstrel

- Baby Huey (singer), rock and soul vocalist

- Mary Haas, linguist

- Jeff Hamilton, jazz drummer[51]

- Del Harris, professional basketball coach

- Micajah C. Henley, roller skate maker

- Charles A. Hufnagel, M.D. artificial heart valve inventor[52]

- C. Francis Jenkins, motion picture and television pioneer

- Harold Jones (drummer), has performed with many notables, including Tony Bennett and Count Basie

- Jim Jones, founder-leader of Peoples Temple

- Melvyn "Deacon" Jones, blues organist

- Daniel Kinsey, hurdler, Olympic gold medalist

- Lamar Lundy, football player, one of the L.A. Rams' "Fearsome Foursome"

- Dan Mitrione, Richmond police chief from 1956–1960, kidnapped and murdered by Tupamaros guerillas while serving as a U.S. adviser in Uruguay in 1970

- Oliver P. Morton, Indiana's Civil War governor[53]

- Marcus Mote, artist

- Rich Mullins, singer/musician

- Addison H. Nordyke, industrialist

- Sarah Purcell, actress

- William Paul Quinn, African Methodist Episcopal Bishop

- Daniel G. Reid, industrialist, philanthropist

- Elizabeth Reller, old-time radio actress

- Ned Rorem, composer and Putlizer Prize winner

- Wendell Stanley, Nobel Prize winner[54]

- D. Elton Trueblood, Quaker theologian[55]

- Levi Coffin, underground railroad organizer, and director of a local Richmond bank.

- Bo Van Pelt, professional golfer

- Burton J. Westcott, automobile manufacturer

- Gaar Williams, cartoonist

- The Will-O-Bees, pop music trio in the 1960s

- Wright brothers, aviation pioneers

Sister cities

See also

- Swayne, Robinson and Company

References

- "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Starr-Gennett Foundation Homepage". Starr-gennett.org. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- "Historical Timeline". WayNet. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Bicentennial Timeline 1795 to 1849". Morrison Reeves Library. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- Millicent Martin Emery (September 12, 2015). "RCS teacher hopes for a musical resurrection". pal-item.com. Palladium-Item. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Rebecca Gross (September 8, 2015). "In Step with Interlochen Center for the Arts". arts.gov. National Endowment for the Arts. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Steve Martin (February 17, 2019). "Out of Our Past: Frederick Douglass made 3 visits to Richmond". pal-item.com. Palladium-Item. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Frederick Douglass (1892). "Life and Times of Frederick Douglass". docsouth.unc.edu. De Wolfe & Fiske Co. p. 287. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Steve Martin (October 14, 2018). "Out of Our Past: How a Richmond speech changed national politics". pal-item.com. Palladium-Item. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Steve Martin (July 14, 2019). "Out of Our Past: Carry Nation, wife of a Wayne County man, condemned 'wicked city'". pal-item.com. Palladium-Item. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved April 20, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Leonard J. Moore, Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921–1928, North Carolina Press, 1997.

- "Spectacular Array Presented by Klan in Mamoth Parade | Ku Klux Klan | Prosecution". Scribd.com. October 6, 1923. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "Parade of Klansmen Chief Public Figure of Ceremonial Here". Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram. October 6, 1923. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- "Klan issue in Democrat race for president", Richmond Item, May 14, 1924, p. 1.

- "Ku Klux Aids Salvation Army". The Richmond Item. December 21, 1922. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- Hoover, Dwight W. (June 1991). "Daisy Douglas Barr: From Quaker to Klan "Kluckeress"". Indiana Magazine of History. 87 (2): 171–195. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Jaspin, Elliot (2008). Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America. New York: Basic Books. Chapter 10 Notes, No. 7. ISBN 0786721979. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- Dwight W. Hoover (June 1991). "Daisy Douglas Barr: From Quaker to Klan "Kluckeress"". Indiana Magazine of History. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- Giants in Their Time: Representative Americans from the Jazz Age to the Cold War, p. 13. Norman K. Risjord, ISBN 0742527859. 2005

- "Starr-Gennett Foundation Walk of Fame". Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Charlie Dahan (April 8, 2014). "April 8th in Gennett History, 1924: Vaughan Quartet Recorded "Wake Up America Kluck Kluck Kluck"". gennett.wordpress.com. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Charlie Dahan (August 2, 2015). "August 2nd in Gennett History, 1924: W. R. Rhinehart Recorded "Klucker And The Rain" and "Long Klucker"". Gennett Records Discography. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- "Home". Richmond Art Museum. June 20, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 5, 2005. Retrieved May 30, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 13, 2006. Retrieved May 30, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Madonna of the Trail – Richmond, Indiana". Waynet.org. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Joseph Moore Museum – Earlham College". Waynet.org. October 16, 2001. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Davis D-1-W". Airventuremuseum.org. November 22, 1933. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- "Davis Monoplane". Davis Monoplane. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- "The Wayne Works Story Part II". CoachBuilt. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Shut Up About the Rose Festival". IshMom.com. August 30, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- Archived January 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "北米の補習授業校一覧(平成25年4月15日現在):文部科学省". Web.archive.org. March 30, 2014. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "ページの本文に移動する". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "Indiana public library directory" (PDF). Indiana State Library. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- FAA Airport Master Record for RID (Form 5010 PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Effective May 31, 2012.

- "Roseview Transit". City of Richmond. October 21, 2007. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- "WCTV | Whitewater Community Television". Wctv.info. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Tiffany Windows – Reid Memorial Presbyterian Church – Wayne County, Indiana". Waynet.org. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- 'Illinois Blue Book 1995-1996,' Biographical Sketch of Bill W. Balthis, pg. 105

- "Weeb Ewbank | Pro Football Hall of Fame Official Site". Profootballhof.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 7, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Dr. Charles A. Hufnagel". Astro4.ast.vill.edu. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Oliver P. Morton Biography Page". Civilwarhome.com. March 24, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Wendell M. Stanley – Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "D. Elton Trueblood, 1900 to 1994". Waynet.org. December 20, 1994. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richmond, Indiana. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Richmond, Indiana. |

- Official website

- Morrison-Reeves Library Digital Collection

- Richmond/Wayne County Convention and Tourism Bureau Inc.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.