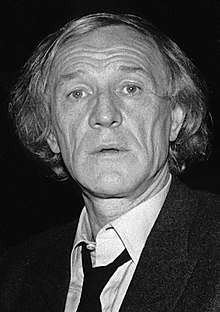

Richard Harris

Richard John Harris (1 October 1930 – 25 October 2002) was an Irish actor and singer. He appeared on stage and in many films, appearing as Frank Machin in This Sporting Life, for which he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor, and King Arthur in the 1967 film Camelot, as well as the 1981 revival of the stage musical.

Richard Harris | |

|---|---|

Harris in 1985 | |

| Born | Richard St John Harris 1 October 1930 Limerick, Ireland |

| Died | 25 October 2002 (aged 72) University College Hospital, London, England |

| Occupation | Actor, singer |

| Years active | 1956–2002 |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Rees-Williams (m. 1957; div. 1969) Ann Turkel (m. 1974; div. 1982) |

| Children | Damian Harris Jared Harris Jamie Harris |

| Relatives | Annabelle Wallis (niece) |

| Signature | |

| |

He played an aristocrat captured by American Indians in A Man Called Horse (1970), a gunfighter in Clint Eastwood's Western film Unforgiven (1992), Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Gladiator (2000), and Albus Dumbledore in the first two Harry Potter films: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001) and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002), the latter of which was his final film role. He was replaced by Michael Gambon for the remainder of the series. Harris had a number-one hit in Australia and Canada and a top-ten hit in the United Kingdom, Ireland and United States with his 1968 recording of Jimmy Webb's song "MacArthur Park".

Early life

Harris was born on 1 October 1930, in Limerick.[1][2]

He was schooled by the Jesuits at Crescent College. A talented rugby player, he appeared on several Munster Junior and Senior Cup teams for Crescent, and played for Garryowen.[3] Harris's athletic career was cut short when he caught tuberculosis in his teens. He remained an ardent fan of the Munster Rugby and Young Munster teams until his death, attending many of their matches, and there are numerous stories of japes at rugby matches with actors and fellow rugby fans Peter O'Toole and Richard Burton.

After recovering from tuberculosis, Harris moved to Great Britain, wanting to become a director. He could not find any suitable training courses, and enrolled in the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) to learn acting. He had failed an audition at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and had been rejected by the Central School of Speech and Drama, because they felt he was too old at 24.[4] While still a student, he rented the tiny "off-West End" Irving Theatre, and there directed his own production of Clifford Odets' play Winter Journey (The Country Girl).

After completing his studies at the Academy, he joined Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop. He began getting roles in West End theatre productions, starting with The Quare Fellow in 1956, a transfer from the Theatre Workshop. He spent nearly a decade in obscurity, learning his profession on stages throughout the UK.[5]

Career

Early supporting roles

Harris made his film debut in 1959 in the film Alive and Kicking, and played the lead role in The Ginger Man in the West End in 1959. His second film was shot in Ireland, a small role as an IRA Volunteer in Shake Hands with the Devil (1959), supporting James Cagney. It was directed by Michael Anderson who offered Harris a role in his next movie, The Wreck of the Mary Deare (1959), shot in Hollywood.

Harris played another IRA Volunteer in A Terrible Beauty (1960), alongside Robert Mitchum. He had a memorable bit part in the film The Guns of Navarone (1961) as a Royal Australian Air Force pilot who reports that blowing up the "bloody guns" of the island of Navarone is impossible by an air raid. He had a larger part in The Long and the Short and the Tall (1961), playing a British soldier; Harris clashed with Laurence Harvey during filming.

For his role in the film Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), despite being virtually unknown to film audiences, Harris reportedly insisted on third billing, behind Trevor Howard and Marlon Brando, an actor he greatly admired, but Harris fell out with Brando over the latter's behaviour during the film's production.

This Sporting Life

Harris's first starring role was in the film This Sporting Life (1963), as a bitter young coal miner, Frank Machin, who becomes an acclaimed rugby league football player. It was based on the novel by David Storey and directed by Lindsay Anderson. For his role, Harris won Best Actor in 1963 at the Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Award nomination.

Harris followed this with a leading role in the Italian film, Michelangelo Antonioni's Il Deserto Rosso (Red Desert, 1964). This won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

Harris received an offer to support Kirk Douglas in a British war film, The Heroes of Telemark (1965), directed by Anthony Mann, playing a Norwegian resistance leader. He then went to Hollywood to support Charlton Heston in Sam Peckinpah's Major Dundee (1965), as an Irish immigrant who became a Confederate cavalryman during the American Civil War.

He played Cain in John Huston's film The Bible: In the Beginning... (1966). More successful at the box office was Hawaii (1966), in which Harris starred alongside Julie Andrews and Max Von Sydow. As a change of pace, he was the romantic lead in a Doris Day spy spoof comedy, Caprice (1967), directed by Frank Tashlin.

Peak of stardom: Camelot, A Man Called Horse, Cromwell

Harris next performed the role of King Arthur in the film adaptation of the musical play Camelot (1967). He continued to appear on stage in this role for many years, including a successful Broadway run in 1981–82.

In The Molly Maguires (1970), he played James McParland, the detective who infiltrates the title organisation, headed by Sean Connery. It was a box office flop. However A Man Called Horse (1970), with Harris in the title role, an 1825 English aristocrat who is captured by Indians, was a major success.

He played the title role in the film Cromwell in 1970 opposite Alec Guinness as King Charles I of England. That year British exhibitors voted him the 9th-most popular star at the UK box office.[6]

Singing career

Harris recorded several albums of music, one of which, A Tramp Shining, included the seven-minute hit song "MacArthur Park" (Harris insisted on singing the lyric as "MacArthur's Park").[7] This song was written by Jimmy Webb, and it reached number 2 on the American Billboard Hot 100 chart. It also topped several music sales charts in Europe during the summer of 1968. "MacArthur Park" sold over one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc.[8] A second album, also consisting entirely of music composed by Webb, The Yard Went on Forever, was released in 1969.[9] In the 1973 TV special "Burt Bacharach in Shangri-La", after singing Webb's "Didn't We", Harris tells Bacharach that since he was not a trained singer he approached songs as an actor concerned with words and emotions, acting the song with the sort of honesty the song is trying to convey. Then he proceeds to sing "If I Could Go Back", from the Lost Horizon soundtrack.

1970s

In 1971 Harris starred in a BBC TV film adaptation The Snow Goose, from a screenplay by Paul Gallico. It won a Golden Globe for Best Movie made for TV and was nominated for both a BAFTA and an Emmy.[10] and was shown in the U.S. as part of the Hallmark Hall of Fame.

He made his directorial debut with Bloomfield (1971) and starred in Man in the Wilderness (1971) a revisionist Western based on the Hugh Glass story.

Action star

Harris starred in a Western for Samuel Fuller, Riata, which stopped production several weeks into filming. The project was re-assembled with a new director and cast, except for Harris, who returned: The Deadly Trackers (1973).

In 1973, Harris published a book of poetry, I, In the Membership of My Days, which was later reissued in part in an audio LP format, augmented by self-penned songs such as "I Don't Know."

Harris starred in two thrillers: 99 and 44/100% Dead (1974), for John Frankenheimer, and Juggernaut (1974), for Richard Lester. In Echoes of a Summer (1976) he played the father of a young girl with a terminal illness. He had a cameo as Richard the Lionheart in Robin and Marian (1976), for Lester, then was in The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976).

Harris led the all-star cast in the train disaster film The Cassandra Crossing (1976). He played Gulliver in the part-animated Gulliver's Travels (1977) and was reunited with Michael Anderson in Orca (1977), battling a killer whale.

He appeared in another action film, Golden Rendezvous (1977), based on a novel by Alistair Maclean, shot in South Africa. Harris was sued by the film's producer for his drinking; Harris counter-sued for defamation and the matter was settled out of court.[11]

Golden Rendezvous was a flop but The Wild Geese (1978), where Harris played one of several mercenaries, was a big success outside America.[12] Ravagers (1979) was more action, set in a post-apocalyptic world. Game for Vultures (1979) was set in Rhodesia and shot in South Africa.

In Hollywood he appeared in a comedy, The Last Word (1979), then supported Bo Derek in Tarzan, the Ape Man (1981).

He made a film in Canada, Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1981), a drama about impotence. He followed it with another Canadian film, Highpoint, a movie so bad it was not released for several years.

Camelot again

Harris's career was revived by his success on stage in Camelot.

His film work during this period included: Triumphs of a Man Called Horse (1983), Martin's Day (1985), Strike Commando 2 (1988), King of the Wind (1990) and Mack the Knife (1990) (a film version of The Threepenny Opera in which he played J.J. Peachum ) plus the TV film version of Maigret, opposite Barbara Shelley. This indicated declining popularity which Harris told his biographer, Michael Feeney Callan, he was "utterly reconciled to".

The Field and Harry Potter

In June 1989, director Jim Sheridan cast Harris in the lead role in The Field, written by the esteemed Irish playwright John B. Keane. The lead role of "Bull" McCabe was to be played by former Abbey Theatre actor Ray McAnally. When McAnally died suddenly on 15 June 1989, Harris was offered the McCabe role. The Field was released in 1990 and earned Harris his second Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. He lost to Jeremy Irons for Reversal of Fortune.

In 1992, Harris had a supporting role in the film Patriot Games, as a fundraiser for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA). He had good roles in Unforgiven (1992), Wrestling Ernest Hemingway (1993) and Silent Tongue (1994). He played the title role in Abraham (1994) and had the lead in Cry, the Beloved Country (1995).

A lifelong supporter of Jesuit education principles,[13] Harris established a friendship with University of Scranton President Rev. J. A. Panuska[14][15] and raised funds for a scholarship for Irish students established in honour of his brother and manager, Dermot, who had died the previous year of a heart attack.[14][15] He chaired acting workshops and cast the university's production of Julius Caesar in November 1987.

Over several years in the late 1980s, Harris worked with Irish author Michael Feeney Callan on his biography, which was published by Sidgwick & Jackson in 1990.

Harris appeared in two films which won the Academy Award for Best Picture. First, as the gunfighter "English Bob" in the Western Unforgiven (1992); second, as the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Ridley Scott's Gladiator (2000). He also played a lead role alongside James Earl Jones in the Darrell Roodt film adaptation of Cry, the Beloved Country (1995). In 1999, Harris starred in the film To Walk with Lions. After Gladiator, Harris played the supporting role of Albus Dumbledore in the first two of the Harry Potter films, and as Abbé Faria in Kevin Reynolds' film adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo (2002). The film Kaena: The Prophecy (2003) was dedicated to him posthumously as he had voiced the character Opaz before his death.

Concerning his role as Dumbledore, Harris had stated that he did not intend to take the part at first, since he knew that his health was in decline, but he relented and accepted it because his 11-year-old granddaughter threatened never to speak to him again if he did not take it.[16] In an interview with the Toronto Star in 2001, Harris expressed his concern that his association with the Harry Potter films would outshine the rest of his career. He explained, "Because, you see, I don't just want to be remembered for being in those bloody films, and I'm afraid that's what's going to happen to me."[17]

Harris also made part of the Bible TV movie project filmed as a cinema production for the TV, a project produced by Lux Vide Italy with the collaboration of Radio Televisione Italiana RAI and Channel 5 of France,[18] and premiered in the United States in the channel TNT in the 1990s. He portrayed the main and title character in the production Abraham (1993) as well as Saint John of Patmos in the 2000 TV film production Apocalypse.

Personal life

In 1957, Harris married Elizabeth Rees-Williams, daughter of David Rees-Williams, 1st Baron Ogmore. They had three children: actor Jared Harris (who was once married to Emilia Fox), actor Jamie Harris, and director Damian Harris, who was once married to Annabel Brooks and was once the partner of Peta Wilson. Harris and Rees-Williams divorced in 1969, after which Elizabeth married Rex Harrison. Harris's second marriage was to the American actress Ann Turkel. In 1982, they divorced.

Harris was a member of the Roman Catholic Knights of Malta, and was also dubbed a knight by the Queen of Denmark in 1985.

Harris paid £75,000 for William Burges' Tower House in Holland Park in 1968, after discovering that the American entertainer Liberace had arranged to buy the house but not yet put down a deposit.[19][20] Harris employed the original decorators, Campbell Smith & Company Ltd. to carry out extensive restoration work on the interior.[20]

Harris was a vocal supporter of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) from 1973 until 1984.[21] In January 1984 remarks he made on the previous month's Harrods bombing caused great controversy, after which he discontinued his support for the PIRA.[22][23][24]

At the height of his stardom in the 1960s and early 1970s Harris was almost as well known for his hellraiser lifestyle and heavy drinking as he was for his acting career. He was a longtime alcoholic until he became a teetotaler in 1981, although he did resume drinking Guinness a decade later. He gave up drugs after almost dying from a cocaine overdose in 1978.

On 25 June 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Richard Harris among hundreds of artists whose master tapes were destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[25]

Illness and death

Harris was diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease in August 2002, reportedly after being hospitalised with pneumonia.[26] He died at University College Hospital in Bloomsbury, London, on 25 October 2002, aged 72.[27] He was survived by his three sons, Damian, Jared and Jamie. He spent his final three days in a coma.[28] Harris's body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in the Bahamas, where he owned a home.[29]

Harris was a lifelong friend of actor Peter O'Toole, and his family reportedly hoped that O'Toole would replace Harris as Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. There were, however, concerns about insuring O'Toole for the six remaining films in the series.[30] Harris was ultimately replaced as Dumbledore by Irish-born actor Michael Gambon.[31]

Memorials

On 30 September 2006, Manuel Di Lucia, of Kilkee, County Clare, a longtime friend, organised the placement in Kilkee of a bronze life-size statue of Richard Harris. It shows Harris at the age of eighteen playing the sport of squash racquets. The sculptor was Seamus Connolly and the work was unveiled by Russell Crowe.[32] Harris was an accomplished squash racquets player, winning the Tivoli Cup in Kilkee four years in a row from 1948 to 1951, a record unsurpassed to this day.[33]

Another life-size statue of Richard Harris, as King Arthur from his film, Camelot, has been erected in Bedford Row, in the centre of his home town of Limerick. The sculptor of this statue was the Irish sculptor Jim Connolly, a graduate of the Limerick School of Art and Design.

At the 2009 BAFTAs, Mickey Rourke dedicated his Best Actor award to Harris, calling him a "good friend and great actor".

In 2013, Rob Gill and Zeb Moore founded the annual Richard Harris International Film Festival.[34] The Richard Harris Film Festival is one of Ireland's fastest-growing film festivals. Growing from just ten films in 2013 to screening over 115 films in 2017. Each year one of Harris's sons attends the annual festival (October Bank Holiday Weekend) in Limerick.

Awards and nominations

Academy Awards

- 1963 – Nominated – Best Actor in a Leading Role – This Sporting Life

- 1990 – Nominated – Best Actor in a Leading Role – The Field

Golden Globes

- 1968 – Won – Best Motion Picture Actor – Musical/Comedy – Camelot

- 1991 – Nominated – Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama – The Field

Primetime Emmy Awards

- 1972 – Nominated – Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role – The Snow Goose

BAFTA Awards

- 1964 – Nominated – Best British Actor – This Sporting Life

Cannes

- 1963 – Won – Best Actor Award – This Sporting Life

Screen Actors Guild Awards

- 2001 – Nominated – Outstanding Performance by the Cast of a Theatrical Motion Picture – Gladiator

Berlin International Film Festival

- 1971 – Nominated – Golden Berlin Bear – Bloomfield

British Independent Film Awards

- 2002 – Nominated – Best Actor – My Kingdom

- 2002 – Won – Outstanding Contribution by an Actor

European Film Awards

- 2000 – Won – Lifetime Achievement Award

Empire Awards

- 2001 – Won – Lifetime Achievement Award

London Film Critics Circle Awards

- 2001 – Won – Dilys Powell Award

Golden Raspberry Awards

- 1982 – Nominated – Worst Actor – Tarzan, the Ape Man

Phoenix Film Critics Society Awards

- 2003 – Nominated – Best Acting Ensemble – Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Grammy Awards

- – Won – Best Spoken Word Recording for Jonathan Livingston Seagull – 1973

- – Nominated – Album of the Year for A Tramp Shining – 1968

- – Nominated – Contemporary Pop Male Vocalist for MacArthur Park – 1968

- – Nominated – Best Spoken Word, Documentary or Drama Recording for The Prophet – 1975

Filmography

Discography

Albums

- Camelot (Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1967)

- A Tramp Shining (1968)

- The Yard Went On Forever (1968)

- The Richard Harris Love Album (1970)

- My Boy (1971)

- Slides (1972)

- His Greatest Performances (1973)

- The Prophet (1974) (music by Arif Mardin, based on The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran)

- I, in the Membership of My Days (1974)

- Gulliver Travels (1977)

- Camelot (Original 1982 London Cast recording) (1982)

- Mack The Knife (Original Soundtrack) (1989)

- Little Tramp (1992) Musical

- The Apocalypse (2004) the story of John the Apostle on Island named Patmos

Singles

- "Here in My Heart (Theme from This Sporting Life)" (1963)

- "How to Handle a Woman (from Camelot)" (1968)

- "MacArthur Park" (1968)

- "Didn't We?" (1968)

- "The Yard Went On Forever" (1968)

- "The Hive" (1969)

- "One of the Nicer Things" (1969)

- "Fill the World With Love" (1969)

- "Ballad of A Man Called Horse" (1970)

- "Morning of the Mourning for Another Kennedy" (1970)

- "Go to the Mirror" (1971)

- "My Boy" (1971)

- "Turning Back the Pages" (1972)

- "Half of Every Dream" (1972)

- "Trilogy (Love, Marriage, Children)" (1974)

- "The Last Castle (Theme from Echoes of a Summer)" (1976)

- "Lilliput (Theme from Gulliver's Travels)" (1977)

CD releases and compilations

- Camelot (Original 1982 London Cast Recording) (1988)

- Mack the Knife (Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1989)

- Tommy (studio recording) (1990)

- Camelot (Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1993)

- A Tramp Shining (1993)

- The Prophet (1995)

- The Webb Sessions 1968–1969 (1996)

- MacArthur Park (1997)

- Slides/My Boy (2-CD Set) (2005)

- My Boy (2006)

- Man of Words Man of Music The Anthology 1968–1974 (2008)

See also

- List of people on the postage stamps of Ireland

References

- "He was one of the most outstanding film stars of his time". Irish Independent. 27 October 2002. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- Severo, Richard (26 October 2002). "Richard Harris, Versatile And Volatile Star, 72, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- "Limerick rugby full of heroes". Wesclark.com. 24 May 2002. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Entertainment | Obituary: Richard Harris". BBC News. 25 October 2002. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Staff Reporter. "Paul Newman Britain's favourite star." Times [London, England] 31 December 1970: 9. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 July 2012.

- Fresh Air interview with Jimmy Webb by Terry Gross on NPR, 2004

- Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-214-20512-5. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Album liner notes for "Richard Harris – the Webb Sessions 1968–1969"

- The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present. Ballantine Books. 2003. p. 1422. ISBN 0-345-45542-8.

- Actor Harris linked to scandal in South Africa, Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file) [Chicago, Ill] 22 Nov 1978: a6.

- Richard Harris: Ain't Misbehavin', Mann, Roderick. Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] 14 Mar 1978: e8.

- Callan, Michael Feeney (2004). Richard Harris: Sex, Death and the Movies. London: Robson Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-1861057662.

- "Harris Welcomed at U.S. University". Lewistown Journal. Associated Press. 18 November 1987. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Richard Harris Establishes Scholarship Fund in Scranton". Ocala Star-Banner. 9 May 1987. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- The Late Show With David Letterman interview, 2001

- Kristin. "On Richard Harris – The Leaky Cauldron". The-leaky-cauldron.org. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Bible Project for TV".

- Cliff Goodwin (31 May 2011). Behaving Badly: Richard Harris. Ebury Publishing. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-0-7535-4651-2. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Caroline Dakers (11 December 1999). The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society. Yale University Press. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-0-300-08164-0. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- Richard Harris: Sex, Death and the Movies (2004) Michael Feeney Callan p267

- "Richard Harris Says IRA Has A Just Cause". Star-Banner. 24 January 1984. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- "Richard Harris ducking IRA "bombs"". The Gettysburg Times. 25 November 1988. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Richard Harris: Sex, Death and the Movies (2004) Michael Feeney Callan p267

- Rosen, Jody (25 June 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- "Entertainment | Harris's Potter role unaffected by illness". BBC News. 30 August 2002. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Richard Harris dies". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. 26 October 2002. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Lionhearted - Death, Richard Harris". People.com. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Entertainment | Obituary: Richard Harris". BBC News. 25 October 2002. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "12 Actors Who Almost Starred In The Harry Potter Series". Fame 10. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "Michael Gambon receives Richard Harris Award and admits ... all I did was copy him as Dumbledore". Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "Crowe pays tribute to Harris at Irish ceremony". BreakingNews.ie. 2 October 2006.

- "Tivoli Cup in Kilkee". kilkee.ie. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- http://www.richardharrisfilmfestival.com

- "7th Moscow International Film Festival (1971)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- "Richard Harris Awards". Retrieved 10 January 2020.

Further reading

- Michael Feeney Callan (1 December 2004). Richard Harris: Sex, Death & the Movies. Robson Books. ISBN 978-1-86105-766-2.

External links

- Richard Harris on IMDb

- Richard Harris at the TCM Movie Database

- Richard Harris at the Internet Broadway Database

- Richard Harris at the BFI's Screenonline

- Richard Harris at Find a Grave

- Richard Harris discography at MusicBrainz

- Harris' Bar Limerick: A Bar in Limerick City Dedicated to Richard

- The Round Table, The Richard Harris Fansite

- Richard Harris file at Limerick City Library, Ireland

- Obituary by Paul Bond at the World Socialist Web Site

- Dumbledore Quotes site