Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović

Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović (pronounced [ɡrǎbar kitǎːroʋitɕ] (![]()

Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| President of Croatia | |

| In office 19 February 2015 – 18 February 2020 | |

| Prime Minister | Zoran Milanović Tihomir Orešković Andrej Plenković |

| Preceded by | Ivo Josipović |

| Succeeded by | Zoran Milanović |

| Assistant Secretary General of NATO for Public Diplomacy | |

| In office 4 July 2011 – 2 October 2014 | |

| Preceded by | Stefanie Babst (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Ted Whiteside (Acting) |

| Ambassador of Croatia to the United States | |

| In office 8 March 2008 – 4 July 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Neven Jurica |

| Succeeded by | Vice Skračić (Acting) |

| Minister of Foreign and European Affairs | |

| In office 17 February 2005 – 12 January 2008 | |

| Prime Minister | Ivo Sanader |

| Preceded by | Miomir Žužul (Foreign Affairs) Herself (European Affairs) |

| Succeeded by | Gordan Jandroković |

| Minister of European Affairs | |

| In office 23 December 2003 – 16 February 2005 | |

| Prime Minister | Ivo Sanader |

| Preceded by | Neven Mimica |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kolinda Grabar 29 April 1968 Rijeka, SR Croatia, SFR Yugoslavia |

| Nationality | Croatian |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | Jakov Kitarović (m. 1996) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents |

|

| Education |

|

| Signature | .jpg) |

| Website | Government website |

Before her election as president of Croatia, Grabar-Kitarović held a number of governmental and diplomatic positions. She was minister of European Affairs from 2003 to 2005, the first female minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration from 2005 to 2008 in both the first and second cabinets of Ivo Sanader, Croatian ambassador to the United States from 2008 to 2011 and assistant secretary general for public diplomacy at NATO under Secretaries General Anders Fogh Rasmussen and Jens Stoltenberg from 2011 to 2014.[5]

She is a recipient of the Fulbright Lifetime Achievement Award and a number of national and international awards, decorations, honorary doctorates and honorary citizenships.[6]

Grabar-Kitarović was a member of the conservative Croatian Democratic Union party from 1993 to 2015[7] and was also one of three Croatian members of the Trilateral Commission,[8] but she was required to resign both positions upon taking office as president in 2015, as Croatian presidents are not permitted to hold other political positions or party membership while in office.[9] In 2017, Forbes magazine listed Grabar-Kitarović as the world's 39th most powerful woman.[10]

Early life and education

Kolinda Grabar was born on 29 April 1968 in Rijeka, Croatia, then part of Yugoslavia, to Dubravka (b. 1947) and Branko Grabar (b. 1944).[11] She was raised mainly in her parents' village of Lopača, just north of Rijeka, where the family owned a butcher shop and a ranch.[11] As a high school student, she entered a student exchange program and at 17 moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico, subsequently graduating from Los Alamos High School in 1986.[11][12]

Upon her return to Yugoslavia, she enrolled at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, graduating in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts in English and Spanish languages and literature.[5][13] From 1995 to 1996, she attended the Diploma Course at the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna.[14] In 2000 she obtained a master's degree in international relations from the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Zagreb.[5]

In 2002–2003 she attended George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs as a Fulbright scholar.[15][16][17] She also received a Luksic Fellowship for the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and was a visiting scholar at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University.[5]

In December 2015, Grabar-Kitarović began her doctoral studies in international relations at the Zagreb Faculty of Political Science.[18]

Career

In 1992, Grabar-Kitarović became an advisor to the international cooperation department of the Ministry of Science and Technology.[19] In 1993 she joined the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ).[20] In the same year she transferred to the Foreign ministry, becoming an advisor.[19] She became the head of the North American department of the Foreign ministry in 1995 and held that post until 1997.[19] That year she began to work at the Croatian embassy in Canada as a diplomatic councilor until October 1998, and then as a minister-councilor.[21]

When Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP) came to power after 2000 elections Tonino Picula became minister of Foreign Affairs. After taking office he immediately started to remove politically appointed staff that was appointed by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) to high-ranking diplomatic positions. Grabar-Kitarović was ordered to return to Croatia from Canada within next six weeks, which she at first refused to do because she was pregnant and had already made plans to give birth in Canada, however, she eventually decided to return after being strongly pressured by the ministry to do so. During her stay in the hospital, she applied for Fulbright scholarship for studying international relations and security policy. She eventually moved to the United States and enrolled at the George Washington University. After graduating, she returned to Croatia and continued to live in Rijeka.

Two years later, she was elected to the Croatian Parliament from the seventh electoral district as a member of the Croatian Democratic Union in the 2003 parliamentary elections.[22] With the formation of the new government led by HDZ chairman Ivo Sanader she became Minister of European integration, which entailed the commencement of negotiations regarding Croatia's ascension to the European Union.[5]

After the separate ministries of Foreign Affairs and European Integration were merged in 2005 Grabar-Kitarović was nominated to become minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration. She was confirmed by the Parliament and sworn in on 17 February 2005.[19] Her main task as foreign minister was to guide Croatia into the European Union and NATO. On 18 January 2005, she became head of the State Delegation for Negotiations on the Croatian accession to the European Union.[5] Furthermore, on 28 November 2005 she was elected by the international community to preside over the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention's Sixth Meeting of the States Parties, or Ottawa Treaty, held that year in Zagreb.[23] Grabar-Kitarović was the first woman to be named president of the Ottawa Treaty.

Following the HDZ's victory in the 2007 parliamentary election and the subsequent formation of the Second Sanader Cabinet, she was reappointed as foreign minister, but was suddenly removed from the position on 12 January 2008. The exact reason for her removal is not known. Gordan Jandroković succeeded her.[24]

On 8 March 2008, while the President of Croatia was Stjepan Mesić, she became the Croatian ambassador to the United States, where she replaced Neven Jurica. She served as ambassador until 4 July 2011. In 2010 a scandal broke out at the Croatian Embassy in Washington, DC when it was revealed that Grabar-Kitarović's husband, Jakov, had been using an official embassy car for private purposes. Namely, a member of the embassy's security staff had followed and filmed Kitarović for days and footage of the events was posted on YouTube, but were later removed. As a result, Foreign Minister Gordan Jandroković launched an internal investigation because of Jakov Kitarović's unauthorized usage of the official car, as the unauthorized filming of members of the diplomatic staff and their families by a member of the embassy's security staff. The investigation concluded that Grabar-Kitarović herself was, despite having an embassy-owned Cadillac DTS with a driver available to her 24 hours a day, using another embassy car, a Toyota Sienna, for private purposes. Grabar-Kitarović claimed that her duties continued for 24 hours a day and that she could not separate her working life from her private life. She later paid for all expenses that occurred due to her husband's unauthorized using of the car, while the member of embassy's security staff who had filmed her family was fired.[25][26][27][28]

In 2011 Grabar-Kitarović submitted her resignation as ambassador and on 4 June 2011 became assistant secretary general of NATO for Public Diplomacy. She was criticized because of the way she left her position in Washington, DC. Namely, Grabar-Kitarović had failed to inform Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor in advance of her plans to resign as ambassador, so Kosor was not prepared to appoint a replacement on time. As a result, the position of Croatian ambassador to the United States was vacant for almost nine months after Grabar-Kitarović's departure. Grabar-Kitarović, however, said that she did in fact inform the newly elected president of Croatia, Social Democrat Ivo Josipović, of her plans and Josipović subsequently confirmed these claims in December 2014, stating that he even gave his personal contribution to her appointment to NATO by writing Grabar-Kitarović a written opinion that she needed from someone reputable. Grabar-Kitarović also said that she had on two occasions offered herself to Prime Minister Kosor and also to return to Croatia, so as to make herself available to the HDZ for the 2011 parliamentary elections. Furthermore, stating that Kosor had just ignored her offers and that it is for this reason that Grabar-Kitarović decided not to communicate with the Prime Minister any further.

When Grabar-Kitarović saw an ad for a job at NATO in The Economist magazine, she thought that the job was well-suited for her, but in the end decided not to apply for it. It was only when NATO failed to choose a candidate for the job in two rounds that she finally applied, and in the third round she received the position. During her term at NATO she often visited Afghanistan and the Croatian soldiers that are deployed there as part of a peacekeeping mission. Her task was to take care of the "communication strategy" and to "bring NATO closer to the common people". Her colleagues at NATO often referred to her as SWAMBO (She Who Must Be Obeyed).[29][30][31][32] Grabar-Kitarović was the first woman ever to be appointed to the position. She served as assistant secretary general in NATO until 2 October 2014.

She was invited to join the Trilateral Commission and became an official member in April 2013.[33]

2014–15 presidential candidacy

Croatian daily newspaper Jutarnji List published an article in September 2012 stating that Grabar-Kitarović was being considered as a possible candidate for the 2014–15 Croatian presidential election by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ).[34][35] It was confirmed in mid-2014 that she was to become the party's official candidate, going up against incumbent Ivo Josipović and newcomers Ivan Vilibor Sinčić and Milan Kujundžić.[36] In the first round of election in December 2014 Grabar-Kitarović won 37.2% of the vote, second to Josipović who received 38.5%, while Sinčić and Kujundžić won 16.4% and 6.3% of the vote respectively.[37] Since no candidate received more than 50% of the vote, a run-off election was scheduled between the top two candidates, Josipović and Grabar-Kitarović, in two weeks time.

Grabar-Kitarović contested the presidential election held in December 2014 and January 2015 as the only female candidate (out of four in total), finishing as the runner-up in the first round and thereafter proceeding to narrowly defeat incumbent President Ivo Josipović in the second round. In the second round, Grabar-Kitarović defeated Josipović (by a margin of 1.48%). Furthermore, as the country had previously also had a female prime minister, Jadranka Kosor, from 2009 until 2011, Grabar-Kitarović's election as president of Croatia also included it into a small group of parliamentary republics which have had both a female head of state and head of government.[38]

The run-off took place on 11 January 2015, with Grabar-Kitarović winning 50.7% of the vote.[39] She thereby became Croatia's first female post-independence head of state and the country's first conservative president in 15 years.[40][Note 1] She was ceremonially sworn into office on 15 February,[41] and assumed office officially at midnight on 19 February 2015.[42]

Upon election, Grabar-Kitarović became the first woman in Europe to defeat an incumbent president running for reelection, as well as the second woman in the world to do so, after Violetta Chamorro of Nicaragua in 1990.[43] She is also the first candidate of any gender to defeat an incumbent Croatian president. In addition, Grabar-Kitarović is the only presidential candidate to date to have won a Croatian presidential election without having won the most votes in the first round of elections, as she lost it by 1.24% or 21,000 votes. Furthermore, the 1.114 million votes she received in the second round is the lowest number of votes for any winning candidate in a presidential election in Croatia and the 1.48% victory margin against Josipović is the smallest in any such election to date.

Presidency (2015–2020)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_01.jpg)

Less than nine months into Grabar-Kitarović's term the European migrant crisis began to escalate with large numbers of migrants entering Greece and Macedonia and crossing from Serbia into Hungary, with the latter beginning the construction of a fence on its southern border as a result.[44] In September 2015, after Hungary constructed a fence and closed its border with Serbia, the flow of migrants was redirected towards Croatia, causing over 21,000 migrants to enter the country[45] by 19 September, with the number rising to 39,000 immigrants, while 32,000 migrants exited Croatia, leaving through Slovenia and Hungary.[46] She appointed Andrija Hebrang her commissioner for the refugee crisis.[47]

With the parliament expected to dissolve by 25 September,[48] Grabar-Kitarović called parliamentary elections for 8 November 2015.[49] They proved inconclusive and negotiations on forming a government lasted for 76 days. Grabar-Kitarović had previously announced on 22 December 2015, if there were no agreement on a possible Prime Minister-designate in the next 24 hours, she would call for an early election and name a non-partisan transitional government (which would have reportedly been headed by Damir Vanđelić), thereby putting intense pressure on the political parties involved in the negotiations regarding the formation of the new government, to find a solution. The crisis finally ended on 23 December 2015 when Grabar-Kitarović gave the 30-day mandate to form a government to the non-partisan Croatian-Canadian businessman Tihomir Orešković, who had been selected by HDZ and MOST only hours before the expiration of the President's delegated time frame for the naming of a Prime-Minister-designate.

On 24 August 2015, Grabar-Kitarović was, as Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief, presented with a petition for the introduction of a Croatian fascist Ustaše movement salute Za dom spremni to the official use in the Croatian Armed Forces. She immediately rejected petition calling it "frivolous, unacceptable and provocative".[50] She called the salute a "Croatian historical greeting" that was "compromised and unacceptable". Following a backlash from historians that the salute was not historical, Grabar-Kitarović admitted that she was wrong in that part of the statement.[51]

On 29 September 2015, at the initiative of Grabar-Kitarović the Atlantic Council co-hosted an informal high-level Adriatic-Baltic-Black Sea Leaders' Meeting in New York City[52] which would later grow to Three Seas Initiative. The Initiative was officially formed in 2016 and held its first summit in Dubrovnik, Croatia, on 25–26 August 2016.[53]

On 11 April 2016, after meeting with Nicolas Dean, the special envoy for Holocaust of the United States Department of State, Grabar-Kitarović stated that the "Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was least independent and was least protecting the interests of the Croatian people". Adding that the "Ustaše regime was criminal regime", that "anti-fascism is in the foundation of the Croatian Constitution" and that the "modern Croatian state has grown on the foundations of the Croatian War of Independence."[54] In May 2016, Grabar-Kitarović visited Tehran on the invitation of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani. Rouhani called on Croatia to be the gateway to Iran's ties with Europe.[55][56] The two presidents reaffirmed the traditionally good relations between their countries and signed an agreement on economic cooperation.[57]

In October 2016, Grabar-Kitarović made an official visit to Baku, Azerbaijan where she expressed her support for the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, stating that the solution to this conflict "must be peaceful and political".[58]

Grabar-Kitarović expressed her condolences to Slobodan Praljak's family after he committed suicide in The Hague where he was facing trial, calling him "a man who preferred to give his life, rather than to live, having been convicted of crimes he firmly believed he had not committed",[59] adding that "his act struck deeply at the heart of the Croatian people and left the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia with the weight of eternal doubt about the accomplishment of its tasks".[60]

In a speech held at the ceremony at which Grabar-Kitarović was named honorary citizen of Buenos Aires in March 2018, she stated that "after World War II, many Croats found a space of freedom in Argentina where they could testify to their patriotism and express their justified demands for the freedom of the Croatian people and homeland." Since a number of Ustasha officials fled to Argentina after WWII, her statement was interpreted by some as support for them. In a press release, Grabar-Kitarović rejected "malicious interpretations" of her statement.[61][62][63] Among the critics was Efraim Zuroff of the Simon Wiesenthal Center who remarked that: "What she was obviously oblivious to was the fact that the wave of immigrants who moved to Argentina after 1945 were Ustasha Nazi war criminals. So if she's proud of them, something is obviously wrong."[64]

During the 2018 FIFA World Cup, held in Russia, Grabar-Kitarović attended the quarter-final and final matches, wearing the colors of the national flag in support of the national team, which ultimately ended up as tournament runners-up.[65] According to the analytics company Mediatoolkit, she "emerged as her country’s star of the tournament" with "25% more focus on her in news stories about the final than any of the players on the pitch", as she "travelled to Russia at her own expense in economy class and often watched from the non-VIP stands".[66] Commenting on the appearance of Croatian nationalist singer Marko Perković Thompson at the celebration, whose songs and concerts are said to glorify the fascist Ustasha regime, and have been banned recently in some places, Grabar-Kitarović stated that she “never heard” such songs nor “seen any evidence that they exist”, was "very fond" of some of his songs and that she did not see any evidence for the controversies associated to him, claiming his songs are "good for national unity". She condemned all totalitarian regimes, including nazism, fascism, and communism.[64][67]

In 2019, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović became the chair of the Council of Women World Leaders, a network of 75 current and former Presidents and Prime Ministers. It is the only organization in the world dedicated to women heads of state and government.

President Grabar-Kitarović is the recipient of numerous foreign awards and decorations. In 2017, she received the Collar of Mubarac the Great in Kuwait, and the National Star of the Republic of Rumania. In 2018, she received the Portuguese Order of Prince Henry and the National Flag Medal of the Republic of Albania. She also received the honorary doctorates from the Slovak Matej Bel University for International relations and economics in 2015, and from Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Hungarian Corvinius University of Budapest, and Argentinean San Pablo University in 2017. She received honorary citizenship of Buenos Aires, Argentina and Mljet, Croatia in 2017, and Berat, Albania in 2018.

During her presidency, she has also received numerous awards, among others the International award “Isa beg Ishaković” in 2015 and “Evening news stamp award” for promoting the European values in 2018, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and EBAN “Visionary Leadership Award” in 2016, as well the “Paul Harris Fellow” of Rotarian Club in 2019. In 2019, she also received the Special recognition for the development of inter-religious dialogue from the Islamic community in Croatia.

Grabar-Kitarović was awarded Fulbright Association's 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award for her "remarkable, contributions as a leader, diplomat, and public servant".[68]

2019–20 Croatian presidential election

In August 2019, during the Victory Day celebrations in Knin, Grabar-Kitarović informally hinted that she would be seeking reelection to a second and final 5-year term as President in the upcoming election,[69] and formally confirmed this several days later in an interview for the right-wing publication Hrvatski tjednik (Croatian Weekly).[70] Prime Minister and HDZ President Andrej Plenković announced that the HDZ will support her bid for second term.[71] On 2 October 2019, Grabar-Kitarović formally announced her bid for re-election with the campaign slogan "Because I believe in Croatia".[72] Her most serious challengers according to the polls were former social democratic Prime Minister Zoran Milanović and conservative musician (and former Member of Parliament) Miroslav Škoro who was supported by nationalist parties.

In August 2019 she announced that she would be seeking a second and final term as president in the upcoming election. She thus proceeded to face 10 other candidates in the first round on 22 December 2019, with her main challengers being former Social Democratic Prime Minister Zoran Milanović and conservative folk musician and former Member of Parliament Miroslav Škoro. Ultimately, Zoran Milanović attained the most votes in the first round (29.55%), thus making Grabar-Kitarović the first Croatian president to not finish in first place in the first round of an election. Furthermore, Grabar-Kitarović managed to defeat Škoro by a margin of only 2.2% of the vote, and therefore narrowly proceeded to the run-off against Milanović. In the second round, held on 5 January 2020, Grabar-Kitarović was defeated in her bid for reelection, gaining 47.34% of the vote against 52.66% for Milanović. She is thus the second (consecutive) President of Croatia to not win a second term, after Ivo Josipović. Also, the number of votes (507,628) and the percentage of the vote (26.65%) that she had received in the first round remain the lowest for any Croatian president to date. Grabar-Kitarović left the presidency on 18 February 2020, when she handed over the office to Zoran Milanović, who thus became the 5th President of Croatia since independence.

The first round of the election took place on 22 December 2019, with Zoran Milanović winning a plurality of 29.55% of the vote, ahead of Grabar-Kitarović, who received 26.65% of the vote.[73] Miroslav Škoro attracted the support of 24.45% of voters.[73] Therefore, this election marked the first time in Croatian history that the incumbent president did not receive the highest number of votes in the first round. Also, Grabar-Kitarović attained both the lowest number of votes (507,626) and the lowest percentage of votes of any Croatian president competing in either of the two rounds of elections. Furthermore, Milanović attained both the lowest number of votes (562,779) and the lowest percentage of the vote of any winning candidate in the first round of a presidential election.[74]

A run-off election took place between Milanović and Grabar-Kitarović on 5 January 2020. If Grabar-Kitarović was to be reelected, her victory would have marked the second instance in a presidential election where the result of the first round was overturned in the run-off, with the first instance of this occurring having been in the 2014–15 election, in which Grabar-Kitarović won her first term. She would also have become the first, and to date only, Croatian president to have never finished first in the first round of a presidential election.

Grabar-Kitarović eventually lost the elections in the second round of voting to Former Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic, who has pledged to make Croatia a tolerant country. Milanovic, the Social Democrat candidate, took 52.7 percent of the vote, while President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic, who had tried to unite a fractured right wing, garnered 47.3 percent. The turnout was about 55 percent.

Political positions

Grabar-Kitarović declared herself a "modern conservative" during the 2014–15 presidential election.[75] Her political positions have mostly been described as conservative in the media.[76][77][78] Agence France-Presse wrote that Grabar-Kitarović represents moderates within her party.[79] Some observers describe her actions as populist,[80][81][82] or nationalist.[83][84]

Grabar-Kitarović opposes same-sex marriage stating that marriage is a matrimony between woman and a man. However, she expressed her support for the Life Partnership Act, which enabled same-sex couples to enjoy rights equal to heterosexual married couples except in adoption, praising it as good compromise.[85]

Grabar-Kitarović considers that the prohibition of abortion would not solve anything, and stresses that attention should be paid to education in order to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Grabar-Kitarović criticized the hard process of adoption and stated that "the whole system has to be reformed so that through education and social measures it enables every woman to give birth to a child, and that mother and the child can eventually be taken care of in an appropriate manner."[86][87]

Grabar-Kitarović has spoken in support of green initiatives along with the dangers of climate change for the environment and global security.[88] In 2016, she signed the Paris Agreement at UN Headquarters in New York City.[89] During another speech at the UN, she stated that climate change was a "powerful weapon of mass destruction."[90]

Personal life

Grabar-Kitarović has been married to Jakov Kitarović since 1996 and they have two children: Katarina (born on 23 April 2001), a figure skater and Croatia's national junior champion; and Luka (born c. 2003).[91][92][93]

Grabar-Kitarović is a practising Roman Catholic.[94] In an interview for HKM (Croatian Catholic Network) she stated that she regularly attends Mass and prays the Rosary.[95]

In an interview for Narodni radio Grabar-Kitarović stated that her favorite singer was Croatian nationalist singer Marko Perković.[96] She awarded Charter of the Republic of Croatia to Prljavo kazalište and stated that they are one of her favourite Croatian rock bands. Grabar-Kitarović also likes Klapa music.

She speaks Croatian, English, Spanish and Portuguese fluently and has basic understanding of German, French and Italian.[5][19]

See also

- Three Seas Initiative

- List of state visits made by Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović

- List of elected and appointed female heads of state

Notes

- Ema Derossi-Bjelajac served as President of the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, a constituent republic of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia and thus held a position equivalent to a head of state

References

- "BIOGRAFIJA KOLINDE GRABAR KITAROVIĆ, PRVE HRVATSKE PREDSJEDNICE Put marljive odlikašice iz Rijeke do Pantovčaka". Jutarnji.hr. 12 January 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Grabar-Kitarovic elected Croatia's first woman president". BBC. 12 January 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic elected president of Croatia". CBC. 11 January 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Hina (15 February 2015). "NOVA PREDSJEDNICA Evo što svjetske agencije javljaju o Kolindinoj inauguraciji". Jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- NATO (29 August 2014). "NATO – Biography: Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic, Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy". NATO.

- https://fulbright.org/2019/08/29/2019-lifetime-achievement-award-kolinda-grabar-kitarovic/

- "Kolinda se javila šefu Karamarku: Izlazim iz HDZ-a". Jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Kolinda Grabar Kitarović - nova nada Hrvatske". Narodni List. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Kolinda više nije članica Rockefellerove Trilaterale, jedne od najmoćnijih grupa na svijetu - Vijesti". Index.hr. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "FORBESOV IZBOR Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović je 39. najmoćnija žena na svijetu". Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "BIOGRAFIJA PRVE ŽENE NA ČELU DRŽAVE". Jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Grabar-Kitarovic to Speak Feb. 14 – News Releases". Library of Congress.

- "Kolinda Grabar Kitarović". vecernji.hr (in Croatian). 1 December 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- "USA - MVEP • Hrvatski". us.mfa.hr. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Officials". AllGov.com. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- "GW News Center". gwu.edu.

- "Presidential Victory for Fulbright Alumna from Croatia | Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs". eca.state.gov. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović i službeno se upisala na doktorski studij - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Kolinda Grabar Kitarović : CV" (PDF). Mvep.hr. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Bogata karijera prve hrvatske predsjednice: 'Prostrana polja, široke ravnice...'" (in Croatian). Dnevnik Nove TV. 11 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Kolinda GRABAR-KITAROVIC – European Forum Alpbach". alpbach.org.

- "Ambassador Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović". NATO after the Wales Summit.

- "Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Sixth Meeting of States Parties". Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- "Croatian Ministers for Foreign Affairs" (in Croatian). Croatian Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs.

- "TKO JOJ PODMEĆE Kolinda mužu dala službeni auto da vozi djecu (VIDEO) > Slobodna Dalmacija > Hrvatska". Slobodnadalmacija.hr. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Životopis prve hrvatske predsjednice Kolinde Grabar-Kitarović — Vijesti.hr". Vijesti.rtl.hr. 12 January 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Kolinda mora vratiti auto i nadoknaditi sve troškove". Jutarnji.hr. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović sigurno u utrci za Pantovčak, Željko Reiner samo rezerva". Jutarnji.hr. 3 January 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Ni mami nije rekla za NATO, pa se ona čudila zašto ponavlja francuski". Jutarnji.hr. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Kolinda Grabar Kitarović za Obris.org: "Odlično sam se snašla"". Obris.org. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Kolindin nadimak Swambo – Ona koju se mora slušati - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. 28 February 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Josipović pomogao lansirati Grabar Kitarović u NATO". tportal.hr. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Archived 27 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tomislav Karamarko: Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović će biti prva žena na čelu Hrvatske!". Jutarnji.hr. 13 September 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- B.V. "Karamarko želi Kolindu Grabar Kitarović za predsjednicu Hrvatske". Dnevnik.hr.

- "Ivo Josipović ili Kolinda Grabar Kitarović – evo što kaže prvo istraživanje!". Večernji.hr.

- "Crveno i plavo: Pogledajte kako su glasali vaši susjedi i prijatelji". Večernji.hr.

- https://www.izbori.hr/site/ostalo/opce-informacije/rezultati-izbora-otvoreni-podaci/izbori-za-predsjednika-republike-hrvatske-478/478

- "Grabar-Kitarović gewinnt Präsidentschaftswahlen in Kroatien". der Standard. Austria.

- Croatians Elect Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic as Their First Female President. The New York Times

- "Croatia will become rich, pledges new president". The Scotsman. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović prisegnula za predsjednicu RH" (in Croatian). HRT. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Tko je najljepša predsjednica na svijetu". Kult portal. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Associated Press in Budapest (13 July 2015). "Hungary begins work on border fence to keep out migrants | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "HRT: U Hrvatsku ušlo oko 21.000 izbjeglica - Mađari ih prihvaćaju bez registracije" (in Croatian). Hrt.hr. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Hina (22 September 2015). "STIGLE NOVE BROJKE U Hrvatsku dosad stiglo 36.000 izbjeglica: 'Bapska nas je iznenadila, ali sada je situacija bolja, dolaze u grupama od 70-ak ljudi'". Jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Piše: R.I.A. (19 September 2015). "Kolindin povjerenik Hebrang: Vojska je trebala na granici tijelima zapriječiti ulazak izbjeglica - Vijesti". Index.hr. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Josip Leko najavio raspuštanje Sabora 25. rujna - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Večernji doznaje: Parlamentarni izbori održat će se najkasnije 15. studenoga - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "BIZARNU PETICIJU POTPISAO I ŠIMUNIĆ Od predsjednice traže da predloži uvođenje pozdrava 'Za dom spremni' u Oružane snage!". Jutarnji.hr. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- "Grabar-Kitarovic: Serbian President's visit to Croatia was not a mistake". N1. 16 February 2019.

- "Adriatic-Baltic-Black Sea Leaders Meeting". atlanticcouncil.org. 29 October 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Dubrovnik Forum adopts declaration called "The Three Seas Initiative"". eblnews.com. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Dragan Matić/ CROPIX (11 April 2016). "KOLINDA GRABAR KITAROVIĆ 'NDH je bila najmanje nezavisna i najmanje je štitila interese Hrvata, a ustaški režim bio je zločinački!' -Jutarnji List". Jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Rouhani: Croatia can be gateway to Iran's ties with Europe". Tehran Times. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Rouhani officially welcomes Croatian president". Tehran Times. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Potvrđeni tradicionalno dobri i prijateljski odnosi Hrvatske i Irana - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "President: Croatia, Azerbaijan "have very good political relations without outstanding issues"". Azernews. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- "Slobodan Praljak: War criminal or Croatian hero?" on Al-Jazeera, 30 November 2017.

- "Predsjednica: Hrvatski narod prvi se odupro velikosrpskoj agresiji braneći svoju opstojnost i opstojnost BiH" [President: The Croatian people first resisted the Greater Serbia aggression by defending its survival and the survival of BiH] (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- "Kolinda: Mnogi su Hrvati u Argentini pronašli slobodu nakon Drugog svjetskog rata".

- "Bauk o Kolindinim izjavama u Argentini: Da je to izjavila Merkel strpali bi je u zatvor".

- "President Rejects "Malicious Interpretations" of Her Speech in Argentina".

- Gadzo, Mersiha (18 August 2018). "How Croatia's World Cup party highlighted 'fascist nostalgia'". Al Jazeera.

- "Emotional Croatian leader Grabar-Kitarovic consoles Modric after World Cup final defeat (PHOTOS)". RT International. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Zagreb, Una Hajdari in (16 July 2018). "Croatia's real World Cup star? The president in the stands". the Guardian. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Grabar-Kitarovic: Everyone is slowly giving up on Bosnia". N1. 27 July 2018.

- "2019 Lifetime Achievement Award: Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović". Fulbright.org. 29 August 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Kolinda u Kninu najavila kandidaturu - i pobjedu: 'I idućih 5 godina ću se viđati ovdje s vama kao predsjednica'". Slobodna Dalmacija. 5 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- "GRABAR-KITAROVIĆ U EKSTREMNO DESNOM LISTU NAJAVILA KANDIDATURU ZA DRUGI MANDAT 'Ne mogu sada okrenuti leđa Hrvatskoj, naravno da idem u kandidaturu'". Jutarnji.hr. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- "Croatia president will run for job again: PM". Reuters. 6 August 2019.

- "President Grabar-Kitarovic formally announces bid for second term in office". N1. 2 October 2019.

- "Zoran Milanović relativni pobjednik izbora, u drugi krug i Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović". novilist.hr. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "Izbori za predsjednika RH 2019. - rezultati". www.izbori.hr. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Komadina, Dragan (2015). "The 2014/2015 Croatian Presidential Election: Tight and Far-reaching Victory of Political Right". Contemporary Southeastern Europe an Interdisciplinary Journal on Southeastern Europe. Zagreb, Croatia: Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Zagreb. 2 (1): 46.

- "Croatia elects conservative in presidential election runoff". The Guardian. 11 January 2015.

- "Grabar-Kitarovic elected Croatia's first woman president". BBC. 12 January 2015.

- "Croatia's president rebukes PM for invitation snub as rift deepens". Reuters. 14 April 2015.

- "Grabar-Kitarovic: Croatia's first female president". Yahoo! News. 11 January 2015.

- "Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic elected president of Croatia". CBC Television. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Holiga, Aleksandar (6 July 2018). "Croatia's World Cup run divides nation where football is never just sport". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Croatia's Serbs: Pawns in a Right-Wing Game". Balkan Insight. 8 June 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Croatians Elect Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic as Their First Female President". The New York Times. 11 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Schatten über Kroatien". Der Standard. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "ŠTO ZAPRAVO ZASTUPAMO Četiri kandidata odgovaraju na 20 teških pitanja Jutarnjeg -Jutarnji List". Jutarnji.hr. 24 December 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- Piše: D.H. ponedjeljak, 31.10.2016. 18:39 (31 October 2016). "Kolinda protiv katoličkih radikala: "Da, ženama treba omogućiti pobačaj kao i do sada" - Vijesti". Index.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Kolinda Grabar Kitarović: Moj osobni stav o pobačaju je poznat, ali zabrana ništa ne rješava > Slobodna Dalmacija". Slobodnadalmacija.hr. 31 October 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Croatian president hails Paris accord as step toward environment-friendly progress". eblnews.com. 23 April 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "Paris Agreement" (PDF). United Nations. 22 April 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "H.E. Ms. Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, President". UN. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "LIJEPA KOLINDINA KĆI BRILJIRA NA LEDU Hoće li nova državna prvakinja Katarina Kitarović braniti boje Hrvatske na Olimpijskim igrama?". Jutarnji list.

- "Suprug Kolinde Grabar Kitarović konačno izašao iz sjene". tportal.hr.

- "Moj suprug nije papučar nego moderan muškarac". Gloria.hr.

- "Moj suprug nije papučar nego moderan muškarac - Gloria". www.gloria.hr. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Idem na mise i redovito molim krunicu". miportal.hr. 4 July 2019.

- "Kolinda otkrila: Djeca su me naučila Thompsonove pjesme". 24 sata.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović. |

- Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović presidential candidacy page

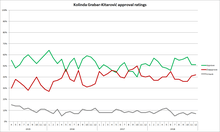

- Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović approval ratings from the start of her Presidency

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Neven Mimica |

Minister of European Integration 2003–2005 |

Position abolished |

| Preceded by Miomir Žužul as Minister of Foreign Affairs |

Minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration 2005–2008 |

Succeeded by Gordan Jandroković |

| Preceded by Herself as Minister of European Integration | ||

| Preceded by Ivo Josipović |

President of Croatia 2015–2020 |

Succeeded by Zoran Milanović |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Neven Jurica |

Ambassador of Croatia to the United States 2008–2011 |

Succeeded by Vice Skračić Acting |

| Preceded by Stefanie Babst Acting |

Assistant Secretary General of NATO for Public Diplomacy 2011–2014 |

Succeeded by Ted Whiteside Acting |

| Preceded by Dalia Grybauskaitė |

Chair of the Council of Women World Leaders 2019–2020 |

Succeeded by Katrín Jakobsdóttir |