Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were American citizens who were convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. The couple were accused of providing top-secret information about radar, sonar, jet propulsion engines, and valuable nuclear weapon designs; at that time the United States was the only country in the world with nuclear weapons. Convicted of espionage in 1951, they were executed by the federal government of the United States in 1953 in the Sing Sing correctional facility in Ossining, New York.[1][2][3]

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg | |

|---|---|

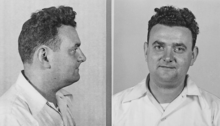

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg in 1951 | |

| Born |

|

| Died |

Ossining, New York, U.S. (both) |

| Resting place | Wellwood Cemetery Suffolk County, New York |

| Occupation | Actress, singer, secretary (Ethel); electrical engineer (Julius) |

| Criminal status | Executed via electric chair |

| Children | Michael Meeropol, Robert Meeropol |

| Criminal charge | Conspiracy to commit espionage |

| Penalty | Death |

Other convicted co-conspirators were sentenced to prison, including Ethel's brother, David Greenglass (who had made a plea agreement), Harry Gold, and Morton Sobell. Klaus Fuchs, a German scientist working in Los Alamos, was convicted in the United Kingdom.[4][5]

For decades, the Rosenbergs' sons, Michael and Robert Meeropol and many other defenders maintained that Julius and Ethel were innocent of spying on their country and were victims of Cold War paranoia. After the fall of the Soviet Union, much information concerning them was declassified, including a trove of decoded Soviet cables, code-named VENONA, which detailed Julius's role as a courier and recruiter for the Soviets and Ethel's role as an accessory. In 2008 the National Archives of the United States published most of the grand jury testimony related to the prosecution of the Rosenbergs; it revealed that Ethel had not been directly involved in activities, though still acted as an accessory, and had full knowledge of Julius's espionage activity and played the main role in the recruitment of her brother for atomic espionage.

In 2014, five historians who had published works based on the Rosenberg case wrote that newly available Soviet documents show that Ethel Rosenberg hid money and espionage paraphernalia for Julius, served as an intermediary for communications with his Soviet intelligence contacts, relayed her personal evaluation of individuals whom Julius considered recruiting, and was present at meetings with his sources.[3] They support the assertion that Ethel persuaded her sister-in-law Ruth Greenglass to travel to New Mexico to recruit her husband David Greenglass as a spy.[3] Other historians, though, argue that this evidence demonstrates only that Ethel knew of her husband's activities and chose to keep quiet.[6]

Early lives and education

Julius Rosenberg was born on May 12, 1918, in New York City to a family of Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. The family moved to the Lower East Side by the time Julius was 11. His parents worked in the shops of the Lower East Side, as Julius attended Seward Park High School. Julius became a leader in the Young Communist League USA while at City College of New York (CCNY), during the Great Depression. In 1939, he graduated from CCNY with a degree in electrical engineering.[7]

Ethel Greenglass was born on September 25, 1915, to a Jewish family in Manhattan, New York City. She had a brother, David Greenglass. She originally was an aspiring actress and singer, but eventually took a secretarial job at a shipping company. She became involved in labor disputes and joined the Young Communist League, where she met Julius in 1936. They married in 1939.[8] Together they had two sons, Michael and Robert, born in 1943 and 1947, respectively.

Espionage

Julius Rosenberg joined the Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, in 1940, where he worked as an engineer-inspector until 1945. He was fired when the US Army discovered his previous membership in the Communist Party. Important research on electronics, communications, radar and guided missile controls was undertaken at Fort Monmouth during World War II.[9]

According to a 2001 book by his former handler Alexander Feklisov, Rosenberg was originally recruited to spy for the interior ministry of the Soviet Union, NKVD, on Labor Day 1942 by former spymaster Semyon Semyonov.[10] By this time, following the invasion by Nazi Germany in June 1941, the Soviet Union had become an ally of the western powers, which included the United States after Pearl Harbour. Rosenberg had been introduced to Semyonov by Bernard Schuster, a high-ranking member of the Communist Party USA and NKVD liaison for Earl Browder. After Semyonov was recalled to Moscow in 1944, his duties were taken over by Feklisov.[10]

Rosenberg provided thousands of classified reports from Emerson Radio, including a complete proximity fuse. Under Feklisov's administration, Rosenberg recruited sympathetic individuals into NKVD service, including Joel Barr, Alfred Sarant, William Perl, and Morton Sobell, also an engineer.[11] Perl supplied Feklisov, under Rosenberg's direction, with thousands of documents from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, including a complete set of design and production drawings for Lockheed's P-80 Shooting Star, the first U.S. operational jet fighter. Feklisov learned through Rosenberg that Ethel's brother David Greenglass was working on the top-secret Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos National Laboratory; he directed Julius to recruit Greenglass.[10]

In February 1944, Rosenberg succeeded in recruiting a second source of Manhattan Project information, engineer Russell McNutt, who worked on designs for the plants at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. For this success, Rosenberg received a $100 bonus. McNutt's employment provided access to secrets about processes for manufacturing weapons-grade uranium.[12][13]

The USSR and the US were allies during World War II, but the Americans did not share information about or seek assistance from the Soviet Union regarding the Manhattan Project. The West was shocked by the speed with which the Soviets were able to stage their first nuclear test, "Joe 1," on August 29, 1949.[14]

Rosenberg case

Arrest

In January 1950, the U.S. discovered that Klaus Fuchs, a German refugee theoretical physicist working for the British mission in the Manhattan Project, had given key documents to the Soviets throughout the war. Fuchs identified his courier as American Harry Gold, who was arrested on May 23, 1950.[15] Gold confessed and identified David Greenglass as an additional source.

On June 15, 1950, David Greenglass was arrested by the FBI for espionage and soon confessed to having passed secret information on to the USSR through Gold. He also claimed that his sister Ethel's husband Julius Rosenberg had convinced David's wife Ruth to recruit him while visiting him in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1944. He said Julius had passed secrets and thus linked him to the Soviet contact agent Anatoli Yakovlev. This connection would be necessary as evidence if there was to be a conviction for espionage of the Rosenbergs.[16][17]

On July 17, 1950, Julius Rosenberg was arrested on suspicion of espionage,[18] based on David Greenglass's confession. On August 11, 1950, Ethel Rosenberg was arrested after testifying before a grand jury (see section, below).[17]

Another accused conspirator, Morton Sobell, fled with his family to Mexico City after Greenglass was arrested. They took assumed names and he tried to figure out a way to reach Europe without a passport. Abandoning that effort, he returned to Mexico City. He claimed that he was kidnapped by members of the Mexican secret police and driven to the U.S. border, where he was arrested by U.S. forces.[19][20] The US government claimed Sobell was arrested by the Mexican police for bank robbery on August 16, 1950, and extradited the next day to the United States in Laredo, Texas.[20] He was charged and tried with the Rosenbergs on one count of conspiracy to commit espionage.

Grand jury

Twenty senior government officials met secretly on February 8, 1950, to discuss the Rosenberg case. Gordon Dean, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, said: "It looks as though Rosenberg is the kingpin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it." Myles Lane, a member of the prosecution team, said that the case against Ethel Rosenberg was "not too strong", but that it was "very important that she be convicted too, and given a stiff sentence."[21]

Their case against Ethel Rosenberg was resolved 10 days before the start of the trial, when David and Ruth Greenglass were interviewed a second time. They were persuaded to change their original stories. David originally had said that he'd passed the atomic data he'd collected to Julius on a New York street corner. After being interviewed this second time, he said that he had given this information to Julius in the living room of the Rosenbergs' New York apartment. Ethel, at Julius's request, had taken his notes and "typed them up." In her re-interview, Ruth Greenglass expanded on her husband's version:

"Julius then took the info into the bathroom and read it and when he came out he called Ethel and told her she had to type this information immediately ... Ethel then sat down at the typewriter which she placed on a bridge table in the living room and proceeded to type the information that David had given to Julius."

As a result of this new testimony, all charges against Ruth Greenglass were dropped.[22]

On August 11, Ethel Rosenberg testified before a grand jury. For all questions, she asserted her right to not answer as provided by the US Constitution's Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination. FBI agents took her into custody as she left the courthouse. Her attorney asked the US Commissioner to parole her in his custody over the weekend, so that she could make arrangements for her two young children. The request was denied.[23] Julius and Ethel were put under pressure to incriminate others involved in the spy ring. Neither offered any further information. On August 17, the grand jury returned an indictment alleging 11 overt acts. Both Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were indicted, as were David Greenglass and Anatoli Yakovlev.[24]

Trial and conviction

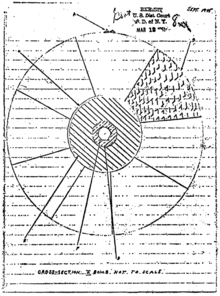

The trial of the Rosenbergs and Sobell on federal espionage charges began on March 6, 1951, in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Irving Kaufman presided over the trial, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Irving Saypol leading the prosecution and criminal defense lawyer Emmanuel Bloch representing the Rosenbergs.[25][26] The prosecution's primary witness, David Greenglass, said that he turned over to Julius Rosenberg a sketch of the cross-section of an implosion-type atom bomb. This was the "Fat Man" bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, as opposed to a bomb with the "gun method" triggering device used in the "Little Boy" bomb dropped on Hiroshima.[27] He also testified that his sister Ethel Rosenberg typed notes containing US nuclear secrets in the Rosenberg apartment in September 1945.

The Rosenbergs both remained defiant as the trial progressed. During testimony, they asserted their right under the US Constitution's Fifth Amendment not to incriminate themselves when asked about their involvement in the Communist Party or their activities with its members.

On March 29, 1951, the Rosenbergs were convicted of espionage. They were sentenced to death on April 5 under Section 2 of the Espionage Act of 1917,[28] which provides that anyone convicted of transmitting or attempting to transmit to a foreign government "information relating to the national defense" may be imprisoned for life or put to death.[29]

Prosecutor Roy Cohn later claimed that his influence led to both Kaufman and Saypol being appointed to the Rosenberg case, and that Kaufman imposed the death penalty based on Cohn's personal recommendation. Cohn would go on later to work for Senator Joseph McCarthy, appointed as Chief Counsel to the investigations subcommittee during McCarthy's tenure as Chairman of the Senate Government Operations Committee.[30]

In imposing the death penalty, Kaufman noted that he held the Rosenbergs responsible not only for espionage but also for American deaths in the Korean War:

"I consider your crime worse than murder ... I believe your conduct in putting into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb has already caused, in my opinion, the Communist aggression in Korea, with the resultant casualties exceeding 50,000 and who knows but that millions more of innocent people may pay the price of your treason. Indeed, by your betrayal, you undoubtedly have altered the course of history to the disadvantage of our country. No one can say that we do not live in a constant state of tension. We have evidence of your treachery all around us every day for the civilian defense activities throughout the nation are aimed at preparing us for an atom bomb attack."[31]

Julius Rosenberg claimed the case was a political frame-up.

After conviction

Campaign for Clemency

After the publication of an investigative series in the National Guardian and the formation of the National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case, some Americans came to believe both Rosenbergs were innocent or had received too harsh a sentence, particularly Ethel. A campaign was started to try to prevent the couple's execution. Between the trial and the executions, there were widespread protests and claims of antisemitism; the charges of antisemitism were widely believed abroad, but not among the vast majority in the United States. At a time when American fears about communism were high, the Rosenbergs did not receive support from mainstream Jewish organizations. The American Civil Liberties Union refused to acknowledge any violations of civil liberties in the case.[32]

Across the world, especially in Western European capitals, there were numerous protests with picketing and demonstrations in favor of the Rosenbergs, along with editorials in otherwise pro-American newspapers, and a plea for clemency from the Pope. President Eisenhower, supported by public opinion and the media at home, ignored the overseas demands.[33]

Jean-Paul Sartre, a Marxist existentialist philosopher and writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, described the trial as

"a legal lynching which smears with blood a whole nation. By killing the Rosenbergs, you have quite simply tried to halt the progress of science by human sacrifice. Magic, witch-hunts, autos-da-fé, sacrifices – we are here getting to the point: your country is sick with fear ... you are afraid of the shadow of your own bomb."[34]

Others, including non-Communists such as Jean Cocteau, Albert Einstein, and Harold Urey, a Nobel Prize–winning physical chemist,[35] as well as Communists or left-leaning artists such as Nelson Algren, Bertolt Brecht, Dashiell Hammett, Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera, protested the position of the American government in what the French termed the US Dreyfus affair.[36] Einstein and Urey pleaded with President Truman to pardon the Rosenbergs. In May 1951, Pablo Picasso wrote for the communist French newspaper L'Humanité, "The hours count. The minutes count. Do not let this crime against humanity take place."[37] The all-black labor union International Longshoremen's Association Local 968 stopped working for a day in protest.[38] Cinema artists such as Fritz Lang registered their protest.[39] Pope Pius XII appealed to President Dwight D. Eisenhower to spare the couple, but Eisenhower refused on February 11, 1953. All other appeals were also unsuccessful.[40][41]

Execution

The United States Federal Bureau of Prisons did not operate an execution chamber when the Rosenbergs were sentenced to death. They were transferred to New York State's Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York, for execution.

The execution was delayed from the originally scheduled date of June 18, because Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas had granted a stay of execution on the previous day. That stay resulted from intervention in the case by Fyke Farmer, a Tennessee lawyer whose efforts had previously been scorned by the Rosenbergs' attorney, Emanuel Hirsch Bloch.[42]

The execution was scheduled for 11 p.m. that evening, during the Jewish Sabbath, which begins and ends around sunset.[43] Bloch asked for more time, filing a complaint that execution on the Sabbath offended the defendants' Jewish heritage. Rhoda Laks, another attorney on the Rosenbergs' defense team, also made this argument before Judge Kaufman.[44] The defense's strategy backfired. Kaufman, who also stated his concerns about executing the Rosenbergs on the Jewish Sabbath, rescheduled the execution for 8 p.m.—before sunset and the Jewish Sabbath and before 11 p.m., the regular time for executions at Sing Sing.[45]

On June 19, 1953, Julius died after the first electric shock. Ethel's execution did not go smoothly. After she was given the normal course of three electric shocks, attendants removed the strapping and other equipment only to have doctors determine that Ethel's heart was still beating. Two more electric shocks were applied, and at the conclusion, eyewitnesses reported that smoke rose from her head.[46] Joseph Francel, then State Electrician of New York, was the executioner.

The funeral services were held in Brooklyn on June 21. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were buried at Wellwood Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery in Pinelawn, New York.[43] The Times reported that 500 people attended, while some 10,000 stood outside:[47]

The bodies had been brought from Sing Sing prison by the national "Rosenberg committee" which undertook the funeral arrangements, and an all-night vigil was held in one of the largest mortuary chapels in Brooklyn. Many hundreds of people filed past the biers. Most of them clearly regarded the Rosenbergs as martyred heroes and more than 500 mourners attended to-day's services, while a crowd estimated at 10,000 stood outside in burning heat. Mr. Bloch [their counsel], who delivered one of the main orations, bitterly exclaimed that America was "living under the heel of a military dictator garbed in civilian attire": the Rosenbergs were "Sweet. Tender. And Intelligent" and the course they took was one of "courage and heroism."

The Rosenbergs were the only two American civilians to be executed for espionage-related activity during the Cold War.[48]

Soviet nuclear program

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, vice-chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, investigated how much the Soviet spy ring helped the USSR to build their bomb. In 1945, Moynihan found, physicist Hans Bethe estimated that the Soviets would be able to build their own bomb in five years. "Thanks to information provided by their agents," Moynihan wrote in his book Secrecy, "they did it in four."[51]

Nikita Khrushchev, leader of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, said in his posthumously published memoir that he "cannot specifically say what kind of help the Rosenbergs provided us" but that he learned from Joseph Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov that they "had provided very significant help in accelerating the production of our atomic bomb."[52]

Boris V. Brokhovich, the engineer who later became director of Chelyabinsk-40, the plutonium production reactor and extraction facility that the Soviet Union used to create its first bomb material, called Khrushchev a "silly fool." He said Soviets had developed their own bomb by trial and error. "You sat the Rosenbergs in the electric chair for nothing," he said. "We got nothing from the Rosenbergs."[53]

The notes allegedly typed by Ethel apparently contained little that was directly used in the Soviet atomic bomb project.[54] According to Alexander Feklisov, the former Soviet agent who was Julius's contact, the Rosenbergs did not provide the Soviet Union with any useful material about the atomic bomb: "He [Julius] didn't understand anything about the atomic bomb and he couldn't help us."[55]

Later developments

Venona decryptions

In 1995, the results of the Venona decryption project were released by the US government, showing Julius Rosenberg's role as the leader of a productive ring of spies.[56] They show Ethel's role was more limited. Neither the Venona decryptions, nor the Vassiliev notebooks published online in 2009, supported historians' assertions about Ethel having a more active role. These historians continued to assert that Julius had reported to the Soviets that Ethel had persuaded Ruth Greenglass to travel to New Mexico to recruit David as a spy.[3] Testimony from Greenglass's trial is not supported by declassified Soviet documents. This suggests that both Greenglasses were enthusiastic recruits into Soviet espionage, needing no persuasion from either Ethel or Julius Rosenberg.

21st-century: Changing accounts and 2008 release of grand jury testimony

In 2001, David Greenglass recanted his testimony about his sister having typed the notes. He said, "I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don't remember."[57] He said he gave false testimony to protect himself and his wife, Ruth, and that he was encouraged by the prosecution to do so. "My wife is more important to me than my sister. Or my mother or my father, OK? And she was the mother of my children."[57]

He refused to express remorse for his decision to betray his sister, saying only that he did not realize that the prosecution would push for the death penalty.[48] He stated, "I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister."[48]

In September 2008, the National Archives released most of the grand jury testimony related to prosecution of the Rosenbergs, as a result of a suit by the National Security Archive at George Washington University, historians and journalists. These revealed irreconcilable differences between Ruth Greenglass's grand jury testimony of August 1950 and the testimony she gave at trial.

At the grand jury, she was asked, "Didn't you write [the information] down on a piece of paper?"[58] She replied, "Yes, I wrote [the information] down on a piece of paper and [Julius Rosenberg] took it with him."[58] But at the trial, she testified that Ethel Rosenberg typed up notes about the atomic bomb.[58] The extent of distortion by the prosecution was shown in their effort to gain a conviction of Ethel Rosenberg.

Numerous articles were published in 2008 related to the Rosenberg case. Deputy Attorney General of the United States William P. Rogers, who had been part of the prosecution of the Rosenbergs, discussed their strategy at the time in relation to seeking the death sentence for Ethel. He said they had urged the death sentence for Ethel in an effort to extract a full confession from Julius. He reportedly said, "She called our bluff," as she made no effort to push her husband to any action.[59]

Morton Sobell

In 2008, Morton Sobell was interviewed after the revelations from grand jury testimony. He admitted that he had given documents to the Soviet contact, but said these had to do with defensive radar and weaponry. He confirmed that Julius Rosenberg was "in a conspiracy that delivered to the Soviets classified military and industrial information ... [on] the atomic bomb," and "He never told me about anything else that he was engaged in."[60]

He said that he thought the hand-drawn diagrams and other atomic-bomb details that were acquired by David Greenglass and passed to Julius were of "little value" to the Soviet Union, and were used only to corroborate what they had already learned from the other atomic spies.[60] He also said that he believed Ethel Rosenberg was aware of her husband's deeds, but took no part in them.[60]

In a subsequent letter to The New York Times, Sobell denied that he knew anything about Julius Rosenberg's alleged atomic espionage activities, and that the only thing he knew for sure was what he himself did in association with Julius Rosenberg.[61]

Rosenberg children

The Rosenbergs' two sons, Michael and Robert, spent years trying to prove the innocence of their parents. They were orphaned by the executions and were not adopted by any relatives. They were adopted by the high school teacher, poet, songwriter, and social activist Abel Meeropol (author of the popular song "Strange Fruit") and his wife Anne, and they assumed the Meeropol surname.

After Morton Sobell's 2008 confession, they acknowledged their father had been involved in espionage, but said that whatever atomic bomb information he passed to the Russians was, at best, superfluous; the case was riddled with prosecutorial and judicial misconduct; their mother was convicted on flimsy evidence to place leverage on her husband; and neither deserved the death penalty.[62]

Michael and Robert co-wrote a book about their and their parents' lives, We Are Your Sons: The Legacy of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg (1975). Robert wrote a later memoir, An Execution in the Family: One Son's Journey (2003). In 1990, he founded the Rosenberg Fund for Children, a nonprofit foundation that provides support for children of targeted liberal activists, and youth who are targeted activists.[63]

Michael's daughter, Ivy Meeropol, directed a 2004 documentary about her grandparents, Heir to an Execution, which was featured at the Sundance Film Festival.[64]

Their sons' current position is that Julius was legally guilty of the conspiracy charge, though not of atomic spying, while Ethel was only generally aware of his activities. The children say that their father did not deserve the death penalty and that their mother was wrongly convicted. They continue to campaign for Ethel to be posthumously legally exonerated.[65]

Campaign for exoneration of Ethel Rosenberg

In 2015, following the most recent grand jury transcript release, Michael and Robert Meeropol called on US President Barack Obama’s administration to acknowledge that Ethel Rosenberg's conviction and execution was wrongful and issue a proclamation to exonerate her.[66]

Similarly, on September 28, 2015, the 100th anniversary of Ethel's birth, 11 members of the New York City Council issued a proclamation stating that "the government wrongfully executed Ethel Rosenberg," and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer officially recognized, "the injustice suffered by Ethel Rosenberg and her family," and declared it, "Ethel Rosenberg Day of Justice in the Borough of Manhattan."

In March 2016, Michael and Robert (via the Rosenberg Fund for Children) launched a petition campaign calling on President Obama and US Attorney General Loretta Lynch to formally exonerate Ethel Rosenberg before the administration left office in January 2017.[67]

In October 2016, the CBS news show 60 Minutes presented the story of the Rosenbergs' children and their quest for their mother's exoneration;[68] however, no US administration has taken action.[69]

In January 2017, before Barack Obama left office, Senator Elizabeth Warren sent the Democratic president a letter requesting a pardon for Ethel Rosenberg.[70]

Artistic representations

- The E. L. Doctorow novel The Book of Daniel (1971) is based on the Rosenberg case as seen through the eyes of a (fictionalized) son. Doctorow wrote the screenplay of the Sidney Lumet film Daniel, starring Timothy Hutton.

- Robert Coover's The Public Burning (1977) dealt with the case. Unlike Doctorow, Coover uses real names for most protagonists of the case, and uses a fictionalized Richard Nixon as his narrator for half of the chapters. This sparked a long delay in the publication of the novel, since publishing houses feared a lawsuit from Nixon.

- Ethel Rosenberg is a major supporting character in Tony Kushner's critically acclaimed play Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes (1993), in which her ghost haunts a dying Roy Cohn. In the HBO 2003 miniseries adaptation of the play, she was portrayed by Meryl Streep.

- Ethel Rosenberg also appears in the memories of Cohn, and then as a spirit to haunt the dying Cohn, in the biography Citizen Cohn as well as its HBO film adaptation.

- Jillian Cantor's The Hours Count (2015) tells the fictional story of a woman who befriends Ethel and Julius Rosenberg and is drawn into their world of intrigue.

- In Audre Lorde's fictionalised autobiography, "Zami", the Rosenbergs appear repeatedly as victims of American McCarthyism

- The main character in Sylvia Plath's novel The Bell Jar is morbidly interested in the Rosenbergs' case.[71] The novel begins with the sentence, "It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn't know what I was doing in New York."

- Images of the Rosenbergs are engraved on a memorial in Havana, Cuba. The accompanying caption says they were murdered.[72]

- The song "Julius and Ethel" by Bob Dylan is based on the Rosenberg case.[73]

See also

- Atom Spies

- Soviet atomic bomb project

Notes

- Radosh, Ronald (June 10, 2016). "Rosenbergs Redux".

- "What the K.G.B. Files Show About Ethel Rosenberg". The New York Times. August 13, 2015.

- Radosh, Ronald; Klehr, Harvey; Haynes, John Earl; Hornblum, Allen M.; Usdin, Steven (October 17, 2014). "The New York Times Gets Greenglass Wrong". Weekly Standard. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- Ranzal, Edward (March 19, 1953). "Greenglass, in Prison, Vows to Kin He Told Truth about Rosenbergs". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

David Greenglass, serving 15 years as a confessed atom spy, denied to members of his family recently that he had been coached by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the drawing of segments of the atom bomb.

- Whitman, Alden (February 14, 1974). "1972 Death of Harry Gold Revealed". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

Harry Gold, who served 15 years in Federal prison as a confessed atomic spy courier, for Klaus Fuchs, a Soviet agent, and who was a key Government witness in the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg espionage case in 1951, died 18 months ago in Philadelphia.

- Lerner, Barron (August 1983). "Books: Sam Roberts's The Brother: The Untold Story of Atomic Spy David Greenglass and How He Sent His Sister, Ethel Rosenberg, to the Electrict Chair". George Washington University History News Network. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- Denison, Charles and Chuck (2004). The Great American Songbook. Author's Choice Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-931741-42-2.

- Martin J. Manning and Clarence R. Wyatt, eds. Encyclopedia of Media and Propaganda in Wartime America, Volume 1 (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2011), 753.

- Wang, Jessica (1999). American Science in An Age of Anxiety. UNC Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-8078-4749-7.

- Feklisov, Aleksandr; Sergei Kostin (2001). The Man Behind the Rosenbergs. Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-08-7.

- Feklisov, Aleksandr; Sergei Kostin (2001). The Man Behind the Rosenbergs. Enigma Books. pp. 140–47. ISBN 978-1-929631-08-7.

- Radosh, Ronald (December 6, 2010). "Rosenbergs Redux". New Republic. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- Haynes, John Earl (2009). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. Yale University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0300155723. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- Ziegler, Charles A.; Jacobson, David (1995). Spying without spies. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-275-95049-1.

- Radosh, Ronald; Milton, Joyce (1997). The Rosenberg file. Yale University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-300-07205-1.

- Theoharis, Athan G. (1999). The FBI: a comprehensive reference guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-89774-991-6.

- "Rosenberg Atomic Espionage Spy Case Chronology" (PDF). National Security Archive at George Washington University. September 11, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/atom-spy-caserosenbergs

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (August 28, 2006). Early Cold War Spies: The Espionage Trials that Shaped American Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781139460248.

- Neville, John F. (1995). The Press, the Rosenbergs, and the Cold War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-275-94995-2.

- Sol Stern and Ronald Radosh, The New Republic (June 23, 1979)

- John Simkin. "Ethel Rosenberg". Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd.

- "Plot to Have G.I. Give Bomb Data to Soviet Is Laid to His Sister Here" (PDF). The New York Times. August 12, 1950. pp. 1, 30.

- "The Atom Spy Case". Famous Cases and Criminals. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- Jenkins, John Philip. "Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg (American spies) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- "Milestones, February 8, 1954". Time. February 8, 1954. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- Roberts, Sam (2003). The Brother: the Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case. Random House. pp. 403–07. ISBN 978-0-375-76124-9.

On February 28, 1945, the NKVD submitted to Lavrenti Beria a comprehensive report on nuclear weaponry, including implosion research, based chiefly on intelligence from Hall and Greenglass.

- 50 USC § 32 (now 18 U.S.C. § 794).

- Huberich, Charles Henry (1918). The law relating to trading with the enemy. Baker, Voorhis & Company. p. 349.

- Ronald Radosh, Joyce Milton, The Rosenberg File p. 278

- "Judge Kaufman's Statement Upon Sentencing the Rosenbergs". University of Missouri–Kansas City. Archived from the original on July 2, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- Radosh, Ronald; Milton, Joyce (1997). The Rosenberg File. Yale University Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-300-07205-1.

- Clune, Lori (2011). "Great Importance World-Wide: Presidential Decision-Making and the Executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg". American Communist History. 10 (3): 263–284. doi:10.1080/14743892.2011.631822.

- Schneir, Walter (1983). Invitation to an Inquest. Pantheon Books. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-394-71496-7.

- Feklisov, Aleksandr; Kostine, Sergei (2001). The Man behind the Rosenbergs. Enigma Books. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-929631-08-7.

The great physicists Albert Einstein and Harold Urey asked President Truman to pardon the couple.

- Radosh, Ronald; Milton, Joyce (1997). The Rosenberg File. Yale University Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-300-07205-1.

But it was the apparent parallel with France's own Dreyfus case that touched the deepest chords in the national psyche.

- Schulte, Elizabeth (May–June 2003). "The trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg". International Socialist Review. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- "Unions throughout U.S. joining in plea to save the Rosenbergs". Daily Worker. January 15, 1953.

- Sharp, Malcolm P. (1956). Was Justice Done? The Rosenberg-Sobell Case. Monthly Review Press. p. 132. 56-10953.

- Schrecker, Ellen (1998). Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown and Company. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-316-77470-3.

- Cortes, Arnaldo (February 14, 1953). "Pope Made Appeal to Aid Rosenbergs". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

Pope Pius XII appealed to the United States Government for clemency in the Rosenberg atomic spy case, the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano revealed today.

- Wood, E. Thomas (June 17, 2007). "Nashville now and then: A lawyer's last gamble". Nashville Post. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

Farmer, working at no charge against the opposition of not only the government but also the Rosenbergs' legal team, showed up at Douglas's chambers without an appointment on the day after the high court adjourned for the term. Farmer convinced Douglas that the Rosenbergs had been tried under an invalid law. If they could be charged with any crime, he asserted, it would have to be a violation of the Atomic Energy Act, which did not carry a death penalty, rather than the Espionage Act of 1917.

- Haberman, Clyde (June 20, 2003). "Executed at Sundown, 50 Years Ago". The New York Times. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

Rosenberg. One more name out of thousands, representing all those souls on their journey through forever at Wellwood Cemetery, along the border between Nassau and Suffolk Counties ... Usually at Sing Sing, the death penalty was carried out at 11 pm. But that June 19 was a Friday, and 11 pm would have pushed the executions well into the Jewish Sabbath, which begins at sundown. The federal judge in Manhattan who sentenced them to death, Irving R. Kaufman, said that the very idea of a Sabbath execution gave him 'considerable concern'. The Justice Department agreed. So the time was pushed forward.

- Ronald Radosh; Joyce Milton (1997). The Rosenberg File. Yale University Press. p. 413. ISBN 9780300072051.

rhoda Laks.

- Roberts, Sam (2003). The Brother: the untold story of the Rosenberg case. Random House. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-375-76124-9.

(According to Orthodox tradition, the Sabbath begins eighteen minutes before sunset Friday and ends the following evening.)

- Philipson, Ilene (1993). Ethel Rosenberg: Beyond the Myths. Rutgers University Press. pp. 351–52. ISBN 978-0-8135-1917-3.

- "Funeral Tributes To Rosenbergs: Execution Denounced". The Times. London. June 21, 1953.(subscription required)

- "False testimony clinched Rosenberg spy trial". BBC News. December 6, 2001. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- "50 years later, Rosenberg execution is still fresh". USA Today. Associated Press. June 17, 2003. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- "Execution of the Rosenbergs". The Guardian. London. June 20, 1953. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed early this morning at Sing Sing Prison for conspiring to pass atomic secrets to Russia in World War II

- Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Secrecy (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1999), 143–44.

- Khrushchev, Nikita (1990). Jerrold L. Schecter; Vyacheslav V. Luchkov (eds.). Khrushchev Remembers: The Glasnost Tapes. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 194.

- McFadden, Robert (September 25, 2008). "Khrushchev on Rosenbergs: Stoking Old Embers". The New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

Nearly four decades after Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed for conspiring to pass America's atomic bomb secrets to the Soviet Union, the case that has haunted scholars, historians and partisans of the left and the right has found a new witness: Nikita S. Khrushchev.

- Roberts, Sam (2001). The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case. Random House. pp. 425–26, 432. ISBN 978-0-375-76124-9.

- Stanley, Alessandra (March 16, 1997). "K.G.B. Agent Plays Down Atomic Role Of Rosenbergs". The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0300084627. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- Robert D. McFadden (October 14, 2014). "David Greenglass, the Brother Who Doomed Ethel Rosenberg, Dies at 92". The New York Times.

- Watt, Holly (September 12, 2008). "Witness Changed Her Story During Rosenberg Spy Case". The Washington Post.

- Roberts, Sam (June 26, 2008). "Spies and Secrecy". The New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

No, he replied, the goal wasn't to kill the couple. The strategy was to use the death sentence imposed on Ethel to wring a full confession from Julius – in hopes that Ethel's motherly instincts would trump unconditional loyalty to a noble but discredited cause. What went wrong? Rogers's explanation still haunts me. 'She called our bluff' he said.

- Roberts, Sam (September 12, 2008). "For First Time, Figure in Rosenberg Case Admits Spying for Soviets". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

Sobell, who served nearly 19 years in Alcatraz and other federal prisons, admitted for the first time that he had been a Soviet spy.

- Morton Sobell (September 19, 2008). "Letter: The Rosenberg Case". The New York Times.

- Roberts, Sam (September 16, 2008). "Father Was a Spy, Sons Conclude With Regret". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

Now, confronted with the surprising confession last week of Morton Sobell, Julius Rosenberg's City College classmate and co-defendant, the brothers have admitted to a painful conclusion: that their father was a spy.

- "My Parents Were Executed Under the Unconstitutional Espionage Act". Democracy Now!. December 30, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- "Sundance: Heir To An Execution". CBS News. January 20, 2004. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- Meeropol, Michael; Meeropol, Robert (August 10, 2015). "The Meeropol Brothers: Exonerate Our Mother, Ethel Rosenberg". The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- "The Meeropol Brothers: Exonerate Our Mother, Ethel Rosenberg". The New York Times. August 10, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Exonerate our Mother, Ethel Rosenberg". Rosenberg Fund for Children. March 1, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- Cooper, Anderson (October 16, 2016). "The Brothers Rosenberg". CBS News. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- "Exiting Obama does not act on request to exonerate Ethel Rosenberg – The Boston Globe". Boston Globe. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- http://theinformedamerican.net/alert-lizzy-warren-caught-asking-for-pardon-of-known-traitor/

- "The Bell Jar: Essay Q&A". Novelguide.com. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- "Rosenberg Memorial". mltranslations.org.

- "Flashback: Hear Bob Dylan's Lost 1983 Song 'Julius and Ethel'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

Works cited

- Feklisov, Aleksandr, and Kostin, Sergei. The Man Behind the Rosenbergs. Enigma Books, 2003. ISBN 978-1-929631-24-7.

- Roberts, Sam. The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case. Random House, 2001. ISBN 0-375-76124-1.

- Schneir, Walter, and Scheir, Miriam. Invitation to an Inquest. Pantheon Books, 1983. ISBN 0-394-71496-2.

- Schrecker, Ellen. Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Little, Brown and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-316-77470-7.

Further reading

- Alman, Emily A. and David. Exoneration: The Trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell – Prosecutorial deceptions, suborned perjuries, anti-Semitism, and precedent for today's unconstitutional trials. Green Elms Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9779058-3-6 or ISBN 0-9779058-3-7.

- Carmichael, Virginia .Framing history: the Rosenberg story and the Cold War, (University of Minnesota Press, 1993).

- Clune, Lori. "Great Importance World-Wide: Presidential Decision-Making and the Executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg." American Communist History 10.3 (2011): 263–284. online

- Doctorow, E. L. The Book of Daniel. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8129-7817-9.

- Goldstein, Alvin H. The Unquiet Death of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, 1975. ISBN 978-0-88208-052-9.

- Harris, "Brian, Injustice", Sutton Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4021-2 (An examination of the trial)

- Hornblum, Allen M. The Invisible Harry Gold: The Man Who Gave the Soviets the Atom Bomb, Yale University Press 2010. ISBN 0-300-15676-6

- Meeropol, Michael, " 'A Spy Who Turned His Family In': Revisiting David Greenglass and the Rosenberg Case," American Communist History (May 2018) available at https://doi.org/10.1080/14743892.2018.1467702

- Meeropol, Michael, ed. The Rosenberg Letters: A Complete Edition of the Prison Correspondence of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. New York: Garland Publishing, 1994. ISBN 0-8240-5948-4.

- Meeropol, Robert and Michael Meeropol. We Are Your Sons: The Legacy of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. University of Illinois Press, 1986. ISBN 0-252-01263-1. Chapter 15 is a detailed refutation of Radosh and Milton's scholarship.

- Meeropol, Robert. An Execution in the Family: One Son's Journey. St. Martin's Press, 2003. ISBN 0-312-30637-7.

- Nason, Tema. Ethel: The Fictional Autobiography of Ethel Rosenberg. Delacourt, 1990. ISBN 0-440-21110-7 and by Syracuse, 2002, ISBN 0-8156-0745-8.

- "David Greenglass grand jury testimony transcript" (PDF). National Security Archive, Gelman Library, George Washington University. August 7, 1950. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Radosh, Ronald and Joyce Milton. The Rosenberg File: A Search for the Truth. Henry Holt (1983). ISBN 0-03-049036-7. a standard scholarly history

- Roberts, Sam. The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case, Random House, 2003, ISBN 0-375-76124-1.

- Roberts, Sam (July 15, 2015). "Secret Grand Jury Testimony From Ethel Rosenberg's Brother Is Released". The New York Times. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Sam Roberts, The Brother: The Untold Story of Atomic Spy David Greenglass and How He Sent His Sister, Ethel Rosenberg, to the Electric Chair, Random House, 2001. ISBN 978-0-375-50013-8.

- Walter Schneir & Miriam Schneir, Invitation to an Inquest: Reopening the Rosenberg Case, 1973. ISBN 978-0-14-003333-5.

- Schneir, Walter. Final Verdict: What Really Happened in the Rosenberg Case, Melville House, 2010. ISBN 1-935554-16-6.

- Trahair, Richard C.S. and Robert Miller. Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations. Enigma Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1-929631-75-9.

- Wexley, John. The Judgment of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Ballantine Books, 1977. ISBN 0-345-24869-4.

- Yalkowsky, Stanley (July 1990). The Murder of the Rosenbergs. Crucible Publications. ISBN 978-0-9620984-2-0.

- Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. p. 434.

- Zion, Sidney. The autobiography of Roy Cohn, Lyle Stuart Inc, 1988. ISBN 0-8184-0471-X.

Other languages

- (in French) Florin Aftalion, La Trahison des Rosenberg, JC Lattès, Paris, 2003.

- (in French) Howard Fast, Mémoire d'un Rouge, éd. Payot & Rivage. Intéressant, traite de toute la période de l'avant seconde guerre mondiale et après (MacCarthysme, etc.) aux États-Unis. Nombreux témoignages. Plusieurs passages sur les Rosenberg notamment pp. 349 à 359.

- (in French) Gérard A. Jaeger, Les Rosenberg. La chaise électrique pour délit d'opinion, Le Félin, 2003.

- (in French) Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Lettres de la maison de la mort, Gallimard, 1953.

- (in French) Morton Sobell, On condamne bien les innocents, Hier et demain, 1974.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rosenberg trial. |

Archival collections

- Guide to the Playscript about the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Espionage Trial. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.-

Other links

- An Interactive Rosenberg Espionage Ring Timeline and Archive

- Timeline of Events Relating to the Rosenberg Trial.

- Rosenberg trial transcript (excerpts as HTML, and the entire 2,563-page transcript as a PDF file)

- Ethel's brother says he trumped up evidence.

- Documents relating to the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Case, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Project Venona messages.

- Rosenberg FBI files (summary only)

- Heir to an Execution – An HBO documentary by Ivy Meeropol, the granddaughter of Ethel and Julius.

- A statement by the Rosenberg's sons in support of their exoneration

- An Interview with Robert Meeropol about the adoption

- National Committee to Reopen the Rosenberg Case

- Annotated bibliography for Ethel Rosenberg from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Annotated bibliography for Julius Rosenberg from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- The Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) for Alexander Vassiliev's Notebooks

- Rosenberg Son: "My Parents Were Executed Under the Unconstitutional Espionage Act"—video report by Democracy Now!

- History on Trial: The Rosenberg Case in E.L. Doctorow's The Book of Daniel by Santiago Juan-Navarro from The Grove: Working Papers on English Studies, Vol 6, 1999.

- Julius Rosenberg at court sentenced to death

- The WSWS speaks to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s son – An interview with Robert Meeropol

- Ethel Rosenberg on IMDb