Interstellar medium

In astronomy, the interstellar medium (ISM) is the matter and radiation that exists in the space between the star systems in a galaxy. This matter includes gas in ionic, atomic, and molecular form, as well as dust and cosmic rays. It fills interstellar space and blends smoothly into the surrounding intergalactic space. The energy that occupies the same volume, in the form of electromagnetic radiation, is the interstellar radiation field.

The interstellar medium is composed of multiple phases distinguished by whether matter is ionic, atomic, or molecular, and the temperature and density of the matter. The interstellar medium is composed, primarily, of hydrogen, followed by helium with trace amounts of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen comparatively to hydrogen.[1] The thermal pressures of these phases are in rough equilibrium with one another. Magnetic fields and turbulent motions also provide pressure in the ISM, and are, typically, more important, dynamically, than the thermal pressure is.

In all phases, the interstellar medium is extremely tenuous by terrestrial standards. In cool, dense regions of the ISM, matter is primarily in molecular form, and reaches number densities of 106 molecules per cm3 (1 million molecules per cm3). In hot, diffuse regions of the ISM, matter is primarily ionized, and the density may be as low as 10−4 ions per cm3. Compare this with a number density of roughly 1019 molecules per cm3 for air at sea level, and 1010 molecules per cm3 (10 billion molecules per cm3) for a laboratory high-vacuum chamber. By mass, 99% of the ISM is gas in any form, and 1% is dust.[2] Of the gas in the ISM, by number 91% of atoms are hydrogen and 8.9% are helium, with 0.1% being atoms of elements heavier than hydrogen or helium,[3] known as "metals" in astronomical parlance. By mass this amounts to 70% hydrogen, 28% helium, and 1.5% heavier elements. The hydrogen and helium are primarily a result of primordial nucleosynthesis, while the heavier elements in the ISM are mostly a result of enrichment in the process of stellar evolution.

The ISM plays a crucial role in astrophysics precisely because of its intermediate role between stellar and galactic scales. Stars form within the densest regions of the ISM, which ultimately contributes to molecular clouds and replenishes the ISM with matter and energy through planetary nebulae, stellar winds, and supernovae. This interplay between stars and the ISM helps determine the rate at which a galaxy depletes its gaseous content, and therefore its lifespan of active star formation.

Voyager 1 reached the ISM on August 25, 2012, making it the first artificial object from Earth to do so. Interstellar plasma and dust will be studied until the mission's end in 2025. Its twin, Voyager 2 entered the ISM in November 2019.

Interstellar matter

Table 1 shows a breakdown of the properties of the components of the ISM of the Milky Way.

| Component | Fractional volume | Scale height (pc) | Temperature (K) | Density (particles/cm3) | State of hydrogen | Primary observational techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular clouds | < 1% | 80 | 10–20 | 102–106 | molecular | Radio and infrared molecular emission and absorption lines |

| Cold neutral medium (CNM) | 1–5% | 100–300 | 50–100 | 20–50 | neutral atomic | H I 21 cm line absorption |

| Warm neutral medium (WNM) | 10–20% | 300–400 | 6000–10000 | 0.2–0.5 | neutral atomic | H I 21 cm line emission |

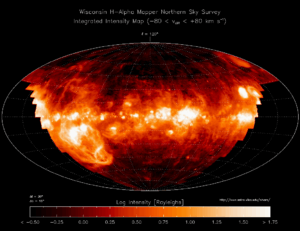

| Warm ionized medium (WIM) | 20–50% | 1000 | 8000 | 0.2–0.5 | ionized | Hα emission and pulsar dispersion |

| H II regions | < 1% | 70 | 8000 | 102–104 | ionized | Hα emission and pulsar dispersion |

| Coronal gas Hot ionized medium (HIM) | 30–70% | 1000–3000 | 106–107 | 10−4–10−2 | ionized (metals also highly ionized) | X-ray emission; absorption lines of highly ionized metals, primarily in the ultraviolet |

The three-phase model

Field, Goldsmith & Habing (1969) put forward the static two phase equilibrium model to explain the observed properties of the ISM. Their modeled ISM consisted of a cold dense phase (T < 300 K), consisting of clouds of neutral and molecular hydrogen, and a warm intercloud phase (T ~ 104 K), consisting of rarefied neutral and ionized gas. McKee & Ostriker (1977) added a dynamic third phase that represented the very hot (T ~ 106 K) gas which had been shock heated by supernovae and constituted most of the volume of the ISM. These phases are the temperatures where heating and cooling can reach a stable equilibrium. Their paper formed the basis for further study over the past three decades. However, the relative proportions of the phases and their subdivisions are still not well known.[3]

The atomic hydrogen model

This model takes into account only atomic hydrogen: Temperature larger than 3000 K breaks molecules, lower than 50 000 K leaves atoms in their ground state. It is assumed that influence of other atoms (He ...) is negligible. Pressure is assumed very low, so that durations of free paths of atoms are larger than the ~ 1 nanosecond duration of light pulses which make ordinary, temporally incoherent light.

In this collisionless gas, Einstein's theory of coherent light-matter interactions applies, all gas-light interactions are spatially coherent. Suppose that a monochromatic light is pulsed, then scattered by molecules having a quadrupole (Raman) resonance frequency. If “length of light pulses is shorter than all involved time constants” (Lamb (1971)), an “impulsive stimulated Raman scattering (ISRS) ” (Yan, Gamble & Nelson (1985)) works: While light generated by incoherent Raman at a shifted frequency has a phase independent on phase of exciting light, thus generates a new spectral line, coherence between incident and scattered light allows their interference into a single frequency, thus shifts incident frequency. Assume that a star radiates a continuous light spectrum up to X rays. Lyman frequencies are absorbed in this light and pump atoms mainly to first excited state. In this state, hyperfine periods are longer than 1 ns, so that an ISRS “may” redshift light frequency, populating high hyperfine levels. Another ISRS “may” transfer energy from hyperfine levels to thermal electromagnetic waves, so that redshift is permanent. Temperature of a light beam is defined from frequency and spectral radiance by Planck's formula. As entropy must increase, “may” becomes “does”. However, where a previously absorbed line (first Lyman beta, ...) reaches Lyman alpha frequency, redshifting process stops and all hydrogen lines are strongly absorbed. But the stop is not perfect if there is energy at frequency shifted to Lyman beta frequency, which produces a slow redshift. Successive redshifts separated by Lyman absorptions generate many absorption lines, frequencies of which, deduced from absorption process, obey a law more dependable than Karlsson's formula.

The previous process excites more and more atoms because a de-excitation obeys Einstein's law of coherent interactions: Variation dI of radiance I of a light beam along a path dx is dI=BIdx, where B is Einstein amplification coefficient which depends on medium. I is the modulus of Poynting vector of field, absorption occurs for an opposed vector, which corresponds to a change of sign of B. Factor I in this formula shows that intense rays are more amplified than weak ones (competition of modes). Emission of a flare requires a sufficient radiance I provided by random zero point field. After emission of a flare, weak B increases by pumping while I remains close to zero: De-excitation by a coherent emission involves stochastic parameters of zero point field, as observed close to quasars (and in polar auroras).

Structures

The ISM is turbulent and therefore full of structure on all spatial scales. Stars are born deep inside large complexes of molecular clouds, typically a few parsecs in size. During their lives and deaths, stars interact physically with the ISM.

Stellar winds from young clusters of stars (often with giant or supergiant HII regions surrounding them) and shock waves created by supernovae inject enormous amounts of energy into their surroundings, which leads to hypersonic turbulence. The resultant structures – of varying sizes – can be observed, such as stellar wind bubbles and superbubbles of hot gas, seen by X-ray satellite telescopes or turbulent flows observed in radio telescope maps.

The Sun is currently traveling through the Local Interstellar Cloud, a denser region in the low-density Local Bubble.

Interaction with interplanetary medium

The interstellar medium begins where the interplanetary medium of the Solar System ends. The solar wind slows to subsonic velocities at the termination shock, 90–100 astronomical units from the Sun. In the region beyond the termination shock, called the heliosheath, interstellar matter interacts with the solar wind. Voyager 1, the farthest human-made object from the Earth (after 1998[5]), crossed the termination shock December 16, 2004 and later entered interstellar space when it crossed the heliopause on August 25, 2012, providing the first direct probe of conditions in the ISM (Stone et al. 2005).

Interstellar extinction

The ISM is also responsible for extinction and reddening, the decreasing light intensity and shift in the dominant observable wavelengths of light from a star. These effects are caused by scattering and absorption of photons and allow the ISM to be observed with the naked eye in a dark sky. The apparent rifts that can be seen in the band of the Milky Way – a uniform disk of stars – are caused by absorption of background starlight by molecular clouds within a few thousand light years from Earth.

Far ultraviolet light is absorbed effectively by the neutral components of the ISM. For example, a typical absorption wavelength of atomic hydrogen lies at about 121.5 nanometers, the Lyman-alpha transition. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to see light emitted at that wavelength from a star farther than a few hundred light years from Earth, because most of it is absorbed during the trip to Earth by intervening neutral hydrogen.

Heating and cooling

The ISM is usually far from thermodynamic equilibrium. Collisions establish a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution of velocities, and the 'temperature' normally used to describe interstellar gas is the 'kinetic temperature', which describes the temperature at which the particles would have the observed Maxwell–Boltzmann velocity distribution in thermodynamic equilibrium. However, the interstellar radiation field is typically much weaker than a medium in thermodynamic equilibrium; it is most often roughly that of an A star (surface temperature of ~10,000 K) highly diluted. Therefore, bound levels within an atom or molecule in the ISM are rarely populated according to the Boltzmann formula (Spitzer 1978, § 2.4).

Depending on the temperature, density, and ionization state of a portion of the ISM, different heating and cooling mechanisms determine the temperature of the gas.

Heating mechanisms

- Heating by low-energy cosmic rays

- The first mechanism proposed for heating the ISM was heating by low-energy cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are an efficient heating source able to penetrate in the depths of molecular clouds. Cosmic rays transfer energy to gas through both ionization and excitation and to free electrons through Coulomb interactions. Low-energy cosmic rays (a few MeV) are more important because they are far more numerous than high-energy cosmic rays.

- Photoelectric heating by grains

- The ultraviolet radiation emitted by hot stars can remove electrons from dust grains. The photon is absorbed by the dust grain, and some of its energy is used to overcome the potential energy barrier and remove the electron from the grain. This potential barrier is due to the binding energy of the electron (the work function) and the charge of the grain. The remainder of the photon's energy gives the ejected electron kinetic energy which heats the gas through collisions with other particles. A typical size distribution of dust grains is n(r) ∝ r−3.5, where r is the radius of the dust particle.[6] Assuming this, the projected grain surface area distribution is πr2n(r) ∝ r−1.5. This indicates that the smallest dust grains dominate this method of heating.[7]

- Photoionization

- When an electron is freed from an atom (typically from absorption of a UV photon) it carries kinetic energy away of the order Ephoton − Eionization. This heating mechanism dominates in H II regions, but is negligible in the diffuse ISM due to the relative lack of neutral carbon atoms.

- X-ray heating

- X-rays remove electrons from atoms and ions, and those photoelectrons can provoke secondary ionizations. As the intensity is often low, this heating is only efficient in warm, less dense atomic medium (as the column density is small). For example, in molecular clouds only hard x-rays can penetrate and x-ray heating can be ignored. This is assuming the region is not near an x-ray source such as a supernova remnant.

- Chemical heating

- Molecular hydrogen (H2) can be formed on the surface of dust grains when two H atoms (which can travel over the grain) meet. This process yields 4.48 eV of energy distributed over the rotational and vibrational modes, kinetic energy of the H2 molecule, as well as heating the dust grain. This kinetic energy, as well as the energy transferred from de-excitation of the hydrogen molecule through collisions, heats the gas.

- Grain-gas heating

- Collisions at high densities between gas atoms and molecules with dust grains can transfer thermal energy. This is not important in HII regions because UV radiation is more important. It is also not important in diffuse ionized medium due to the low density. In the neutral diffuse medium grains are always colder, but do not effectively cool the gas due to the low densities.

Grain heating by thermal exchange is very important in supernova remnants where densities and temperatures are very high.

Gas heating via grain-gas collisions is dominant deep in giant molecular clouds (especially at high densities). Far infrared radiation penetrates deeply due to the low optical depth. Dust grains are heated via this radiation and can transfer thermal energy during collisions with the gas. A measure of efficiency in the heating is given by the accommodation coefficient:

where T is the gas temperature, Td the dust temperature, and T2 the post-collision temperature of the gas atom or molecule. This coefficient was measured by (Burke & Hollenbach 1983) as α = 0.35.

- Other heating mechanisms

- A variety of macroscopic heating mechanisms are present including:

- Gravitational collapse of a cloud

- Supernova explosions

- Stellar winds

- Expansion of H II regions

- Magnetohydrodynamic waves created by supernova remnants

Cooling mechanisms

- Fine structure cooling

- The process of fine structure cooling is dominant in most regions of the Interstellar Medium, except regions of hot gas and regions deep in molecular clouds. It occurs most efficiently with abundant atoms having fine structure levels close to the fundamental level such as: C II and O I in the neutral medium and O II, O III, N II, N III, Ne II and Ne III in H II regions. Collisions will excite these atoms to higher levels, and they will eventually de-excite through photon emission, which will carry the energy out of the region.

- Cooling by permitted lines

- At lower temperatures, more levels than fine structure levels can be populated via collisions. For example, collisional excitation of the n = 2 level of hydrogen will release a Ly-α photon upon de-excitation. In molecular clouds, excitation of rotational lines of CO is important. Once a molecule is excited, it eventually returns to a lower energy state, emitting a photon which can leave the region, cooling the cloud.

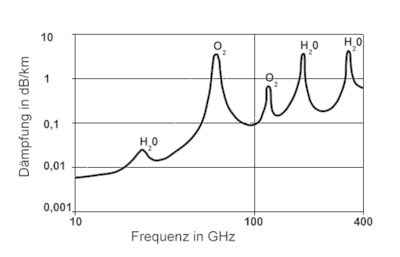

Radiowave propagation

Radio waves from ≈10 kHz (very low frequency) to ≈300 GHz (extremely high frequency) propagate differently in interstellar space than on the Earth's surface. There are many sources of interference and signal distortion that do not exist on Earth. A great deal of radio astronomy depends on compensating for the different propagation effects to uncover the desired signal.[8][9]

Discoveries

In 1864, William Huggins uses spectroscopy to determine that a nebula is made of gas.[10] Huggins had a private observatory with a 8-inch telescope, with a lens by Alvin Clark; but it was equipped for spectroscopy which enabled breakthrough observations.[11]

In 1904, one of the discoveries made using the Potsdam Great Refractor telescope was of Calcium in the interstellar medium.[12] The astronomer Professor Hartmann determined from spectrograph observations of the binary star Mintaka in Orion, that there was the element calcium in the intervening space.[12]

Interstellar gas was further confirmed by Slipher in 1909, and then by 1912 interstellar dust was confirmed by Slipher.[13] In this way the overall nature of the interstellar medium was confirmed in a series of discoveries and postulizations of its nature.[14]

History of knowledge of interstellar space

.tif.jpg)

The nature of the interstellar medium has received the attention of astronomers and scientists over the centuries, and understanding of the ISM has developed. However, they first had to acknowledge the basic concept of "interstellar" space. The term appears to have been first used in print by Bacon (1626, § 354–5): "The Interstellar Skie.. hath .. so much Affinity with the Starre, that there is a Rotation of that, as well as of the Starre." Later, natural philosopher Robert Boyle (1674) discussed "The inter-stellar part of heaven, which several of the modern Epicureans would have to be empty."

Before modern electromagnetic theory, early physicists postulated that an invisible luminiferous aether existed as a medium to carry lightwaves. It was assumed that this aether extended into interstellar space, as Patterson (1862) wrote, "this efflux occasions a thrill, or vibratory motion, in the ether which fills the interstellar spaces."

The advent of deep photographic imaging allowed Edward Barnard to produce the first images of dark nebulae silhouetted against the background star field of the galaxy, while the first actual detection of cold diffuse matter in interstellar space was made by Johannes Hartmann in 1904[16] through the use of absorption line spectroscopy. In his historic study of the spectrum and orbit of Delta Orionis, Hartmann observed the light coming from this star and realized that some of this light was being absorbed before it reached the Earth. Hartmann reported that absorption from the "K" line of calcium appeared "extraordinarily weak, but almost perfectly sharp" and also reported the "quite surprising result that the calcium line at 393.4 nanometres does not share in the periodic displacements of the lines caused by the orbital motion of the spectroscopic binary star". The stationary nature of the line led Hartmann to conclude that the gas responsible for the absorption was not present in the atmosphere of Delta Orionis, but was instead located within an isolated cloud of matter residing somewhere along the line-of-sight to this star. This discovery launched the study of the Interstellar Medium.

In the series of investigations, Viktor Ambartsumian introduced the now commonly accepted notion that interstellar matter occurs in the form of clouds.[17]

Following Hartmann's identification of interstellar calcium absorption, interstellar sodium was detected by Heger (1919) through the observation of stationary absorption from the atom's "D" lines at 589.0 and 589.6 nanometres towards Delta Orionis and Beta Scorpii.

Subsequent observations of the "H" and "K" lines of calcium by Beals (1936) revealed double and asymmetric profiles in the spectra of Epsilon and Zeta Orionis. These were the first steps in the study of the very complex interstellar sightline towards Orion. Asymmetric absorption line profiles are the result of the superposition of multiple absorption lines, each corresponding to the same atomic transition (for example the "K" line of calcium), but occurring in interstellar clouds with different radial velocities. Because each cloud has a different velocity (either towards or away from the observer/Earth) the absorption lines occurring within each cloud are either blue-shifted or red-shifted (respectively) from the lines' rest wavelength, through the Doppler Effect. These observations confirming that matter is not distributed homogeneously were the first evidence of multiple discrete clouds within the ISM.

The growing evidence for interstellar material led Pickering (1912) to comment that "While the interstellar absorbing medium may be simply the ether, yet the character of its selective absorption, as indicated by Kapteyn, is characteristic of a gas, and free gaseous molecules are certainly there, since they are probably constantly being expelled by the Sun and stars."

The same year Victor Hess's discovery of cosmic rays, highly energetic charged particles that rain onto the Earth from space, led others to speculate whether they also pervaded interstellar space. The following year the Norwegian explorer and physicist Kristian Birkeland wrote: "It seems to be a natural consequence of our points of view to assume that the whole of space is filled with electrons and flying electric ions of all kinds. We have assumed that each stellar system in evolutions throws off electric corpuscles into space. It does not seem unreasonable therefore to think that the greater part of the material masses in the universe is found, not in the solar systems or nebulae, but in 'empty' space" (Birkeland 1913).

Thorndike (1930) noted that "it could scarcely have been believed that the enormous gaps between the stars are completely void. Terrestrial aurorae are not improbably excited by charged particles emitted by the Sun. If the millions of other stars are also ejecting ions, as is undoubtedly true, no absolute vacuum can exist within the galaxy."

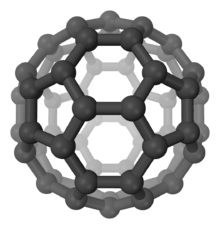

In September 2012, NASA scientists reported that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), subjected to interstellar medium (ISM) conditions, are transformed, through hydrogenation, oxygenation and hydroxylation, to more complex organics – "a step along the path toward amino acids and nucleotides, the raw materials of proteins and DNA, respectively".[19][20] Further, as a result of these transformations, the PAHs lose their spectroscopic signature which could be one of the reasons "for the lack of PAH detection in interstellar ice grains, particularly the outer regions of cold, dense clouds or the upper molecular layers of protoplanetary disks."[19][20]

In February 2014, NASA announced a greatly upgraded database[21] for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe. According to scientists, more than 20% of the carbon in the universe may be associated with PAHs, possible starting materials for the formation of life. PAHs seem to have been formed shortly after the Big Bang, are widespread throughout the universe, and are associated with new stars and exoplanets.[22]

In April 2019, scientists, working with the Hubble Space Telescope, reported the confirmed detection of the large and complex ionized molecules of buckminsterfullerene (C60) (also known as "buckyballs") in the interstellar medium spaces between the stars.[23][24]

See also

- Astrophysical maser

- Cosmic dust

- Diffuse interstellar band

- Fossil stellar magnetic field

- Heliosphere

- List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

- List of plasma physics articles

- Molecular clouds

- Photodissociation region

References

Citations

- Herbst, Eric (1995). "Chemistry in The Interstellar Medium". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 46: 27–54. Bibcode:1995ARPC...46...27H. doi:10.1146/annurev.pc.46.100195.000331.

- Boulanger, F.; Cox, P.; Jones, A. P. (2000). "Course 7: Dust in the Interstellar Medium". In F. Casoli; J. Lequeux; F. David (eds.). Infrared Space Astronomy, Today and Tomorrow. p. 251. Bibcode:2000isat.conf..251B.

- (Ferriere 2001)

- "The Pillars of Creation Revealed in 3D". European Southern Observatory. 30 April 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- "Voyager: Fast Facts". Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- Mathis, J.S.; Rumpl, W.; Nordsieck, K.H. (1977). "The size distribution of interstellar grains". Astrophysical Journal. 217: 425. Bibcode:1977ApJ...217..425M. doi:10.1086/155591.

- Weingartner, J.C.; Draine, B.T. (2001). "Photoelectric Emission from Interstellar Dust: Grain Charging and Gas Heating". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 134 (2): 263–281. arXiv:astro-ph/9907251. Bibcode:2001ApJS..134..263W. doi:10.1086/320852.

- Samantha Blair. "Interstellar Medium Interference (video)". SETI Talks.

- "Voyager 1 Experiences Three Tsunami Waves in Interstellar Space (video)". JPL.

- "The First Planetary Nebula Spectrum". Sky & Telescope. 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- "William Huggins (1824-1910)". www.messier.seds.org. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- Kanipe, Jeff (2011-01-27). The Cosmic Connection: How Astronomical Events Impact Life on Earth. Prometheus Books. ISBN 9781591028826.

- "A geyser of hot gas flowing from a star". ESA/Hubble Press Release. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Asimov, Isaac, Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology (2nd ed.)

- S. Chandrasekhar (1989), "To Victor Ambartsumian on his 80th birthday", Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy, 18 (1): 408–409, Bibcode:1988Ap.....29..408C, doi:10.1007/BF01005852

- "Hubble sees a cosmic caterpillar". Image Archive. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Staff (September 20, 2012), NASA Cooks Up Icy Organics to Mimic Life's Origins, Space.com, retrieved September 22, 2012

- Gudipati, Murthy S.; Yang, Rui (September 1, 2012), "In-Situ Probing Of Radiation-Induced Processing Of Organics In Astrophysical Ice Analogs—Novel Laser Desorption Laser Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectroscopic Studies", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 756 (1): L24, Bibcode:2012ApJ...756L..24G, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/756/1/L24

- "PAH IR Spectroscopic Database". The Astrophysics & Astrochemistry Laboratory. NASA Ames Research Center. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- Hoover, Rachel (February 21, 2014). "Need to Track Organic Nano-Particles Across the Universe? NASA's Got an App for That". NASA. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- Starr, Michelle (29 April 2019). "The Hubble Space Telescope Has Just Found Solid Evidence of Interstellar Buckyballs". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Cordiner, M.A.; et al. (22 April 2019). "Confirming Interstellar C60 + Using the Hubble Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 875 (2): L28. arXiv:1904.08821. Bibcode:2019ApJ...875L..28C. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab14e5.

Sources

- Bacon, Francis (1626), Sylva (3545 ed.)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beals, C. S. (1936), "On the interpretation of interstellar lines", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 96 (7): 661–678, Bibcode:1936MNRAS..96..661B, doi:10.1093/mnras/96.7.661CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Birkeland, Kristian (1913), "Polar Magnetic Phenomena and Terrella Experiments", The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition, 1902-03 (section 2), New York: Christiania (now Oslo), H. Aschelhoug & Co., p. 720 out-of-print, full text online

- Boyle, Robert (1674), The Excellency of Theology Compar'd with Natural Philosophy, ii. iv., p. 178CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burke, J. R.; Hollenbach, D.J. (1983), "The gas-grain interaction in the interstellar medium – Thermal accommodation and trapping", Astrophysical Journal, 265: 223, Bibcode:1983ApJ...265..223B, doi:10.1086/160667CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dyson, J. (1997), Physics of the Interstellar Medium, London: Taylor & FrancisCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Field, G. B.; Goldsmith, D. W.; Habing, H. J. (1969), "Cosmic-Ray Heating of the Interstellar Gas", Astrophysical Journal, 155: L149, Bibcode:1969ApJ...155L.149F, doi:10.1086/180324CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferriere, K. (2001), "The Interstellar Environment of our Galaxy", Reviews of Modern Physics, 73 (4): 1031–1066, arXiv:astro-ph/0106359, Bibcode:2001RvMP...73.1031F, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.73.1031CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haffner, L. M.; Reynolds, R. J.; Tufte, S. L.; Madsen, G. J.; Jaehnig, K. P.; Percival, J. W. (2003), "The Wisconsin Hα Mapper Northern Sky Survey", Astrophysical Journal Supplement, 145 (2): 405, arXiv:astro-ph/0309117, Bibcode:2003ApJS..149..405H, doi:10.1086/378850. The Wisconsin Hα Mapper is funded by the National Science Foundation.

- Heger, Mary Lea (1919), "Stationary Sodium Lines in Spectroscopic Binaries", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 31 (184): 304, Bibcode:1919PASP...31..304H, doi:10.1086/122890CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamb, G. L. (1971), "Analytical Descriptions of Ultrashort Optical Pulse Propagation in a Resonant Medium", Reviews of Modern Physics, 43 (2): 99–124, Bibcode:1971RvMP...43...99L, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.43.99CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lequeux, James (2005), The Interstellar Medium (PDF), Astronomy and Astrophysics Library, Springer, Bibcode:2005ism..book.....L, doi:10.1007/B137959, ISBN 978-3-540-21326-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKee, C. F.; Ostriker, J. P. (1977), "A theory of the interstellar medium – Three components regulated by supernova explosions in an inhomogeneous substrate", Astrophysical Journal, 218: 148, Bibcode:1977ApJ...218..148M, doi:10.1086/155667CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Robert Hogarth (1862), "Colour in nature and art", Essays in History and Art, 10. Reprinted from Blackwood's Magazine

- Pickering, W. H. (1912), "The Motion of the Solar System relatively to the Interstellar Absorbing Medium", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 72 (9): 740–743, Bibcode:1912MNRAS..72..740P, doi:10.1093/mnras/72.9.740

- Spitzer, L. (1978), Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-29335-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stone, E. C.; Cummings, A. C.; McDonald, F. B.; Heikkila, B. C.; Lal, N.; Webber, W. R. (2005), "Voyager 1 Explores the Termination Shock Region and the Heliosheath Beyond", Science, 309 (5743): 2017–20, Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2017S, doi:10.1126/science.1117684, PMID 16179468CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thorndike, S. L. (1930), "Interstellar Matter", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 42 (246): 99, Bibcode:1930PASP...42...99T, doi:10.1086/124007CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yan, Yong‐Xin; Gamble, Edward B.; Nelson, Keith A. (December 1985). "Impulsive stimulated scattering: General importance in femtosecond laser pulse interactions with matter, and spectroscopic applications". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 83 (11): 5391–5399. Bibcode:1985JChPh..83.5391Y. doi:10.1063/1.449708.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Interstellar media. |