Interstate 5 in Washington

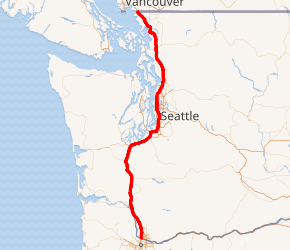

Interstate 5 (I-5) is an Interstate Highway on the West Coast of the United States, serving as the region's primary north–south route. It travels 277 miles (446 km) across the state of Washington, running from the Oregon state border at Vancouver, through the Puget Sound region, and to the Canadian border at Blaine. Within the Seattle metropolitan area, the freeway connects the cities of Tacoma, Seattle, and Everett.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purple Heart Trail | ||||

A map of Western Washington with I-5 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Defined by RCW 47.17.020 | ||||

| Maintained by WSDOT | ||||

| Length | 276.62 mi[1][2] (445.18 km) | |||

| Existed | August 14, 1957[3][4]–present | |||

| History | Completed in 1969[5] | |||

| Tourist routes |

| |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end | ||||

| North end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Counties | Clark, Cowlitz, Lewis, Thurston, Pierce, King, Snohomish, Skagit, Whatcom | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

I-5 is the only interstate to traverse the whole state from north to south and is Washington's busiest highway, with an average of 274,000 vehicles traveling on it through Downtown Seattle on a typical day. The segment in Downtown Seattle is also among the widest freeways in the United States, at 13 lanes, and includes a set of express lanes that reverse direction depending on time of the day. Most of the freeway is four lanes in rural areas and six to eight lanes in suburban areas, utilizing a set of high-occupancy vehicle lanes in the latter. I-5 also has three related auxiliary Interstates in the state, I-205, I-405, and I-705, as well as several designated business routes and state routes.

The freeway follows several historic railroads and wagon trails developed during American settlement of western Washington in the mid-to-late 19th century. The state legislature incorporated local roads into the Pacific Highway in 1913, connecting the state's southern and northern borders between Vancouver and Blaine. The Pacific Highway was built and paved over the next decade, and became the northernmost segment of the national U.S. Route 99 (US 99) in 1926.

The federal government endorsed the creation of a national expressway system in the 1940s, including several bypasses on US 99 that were built by the state in the early 1950s. The state's planned toll superhighway in the Seattle area was shelved in favor of a federally-funded freeway under the new Interstate Highway System, under which I-5 was created in 1957. Construction of I-5 was completed in 1969, and several segments of the highway have been widened or improved in the decades since.

Route description

Interstate 5 is the only Interstate to traverse Washington from north to south, serving as the primary highway for the western portion of the state.[6] It is listed as part of the National Highway System, identifying routes that are important to the national economy, defense, and mobility, and the state's Highway of Statewide Significance program, recognizing its connection to major communities.[7][8] I-5 has three auxiliary Interstate Highways within Washington: I-205, an easterly bypass of Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver; I-405, bypassing Seattle via the Eastside; and I-705, a short spur into Tacoma.[9][10] It was designated as the Purple Heart Trail in 2013 by the Washington State Transportation Commission to honor wounded military veterans.[11]

The freeway runs through the most densely populated region of Washington state, with 4.6 million people living in the nine counties on the corridor, approximately 70 percent of the state's population.[12][13] Several of the largest cities along the I-5 corridor are also connected by Cascades, a regional train service between Eugene, Oregon, and Vancouver, British Columbia, operated by Amtrak and funded by the state governments of Oregon and Washington.[14][15]

I-5 is maintained by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), who conduct an annual survey of traffic volume that is expressed in terms of average annual daily traffic (AADT), a measure of traffic volume for any average day of the year. The stretch of I-5 through Downtown Seattle is the busiest highway in Washington state, with a daily average of over 274,000 vehicles in the mainline and express lanes.[16] The least-traveled segment of I-5 is located at SR 548 in Blaine, with a daily average of 6,600 vehicles.[17] Traffic congestion I-5 through the Seattle metropolitan area is among the worst in the United States, with 78 percent of peak direction miles classified as "routinely congested" for 7–8 hours a day and an average annual delay of 55 hours for the Seattle–Everett corridor.[18][19][20] The freeway has a maximum speed limit of 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) in rural areas and 60 mph (97 km/h) in urban and suburban areas, which includes a 100-mile (160 km) section between Tumwater and Marysville.[1][21]

Southwestern Washington

I-5 enters Washington on the Interstate Bridge, a pair of vertical-lift bridges that span the Columbia River between Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington. The bridge is the only point on I-5 where vehicles have to stop for cross traffic, due to the lifts.[22] On the north bank of the river, the freeway passes under a railroad viaduct carrying Amtrak's Empire Builder and intersects SR 14. The interchange with SR 14, located west of Pearson Field and the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, also includes ramps serving downtown Vancouver.[23][24] I-5 continues north through suburban Vancouver and into Hazel Dell, passing the Clark College campus and intersecting SR 501 at Fourth Plain Boulevard and SR 500 at Burnt Bridge Creek. I-5 intersects I-205, the eastern freeway bypass of the Portland metropolitan area, in Salmon Creek near the Vancouver campus of Washington State University.[25]

From Salmon Creek, I-5 continues northwesterly and intersects SR 502 at the Gee Creek rest area west of Battle Ground.[26] Its next interchange, in eastern Ridgefield, forms the eastern terminus of SR 501. The freeway passes the Ilani Casino Resort on the Cowlitz reservation and crosses the Lewis River into Woodland, where it intersects SR 503. Northwest of Woodland, the median of I-5 is used by freight trains and Amtrak's Cascades and Coast Starlight passenger trains, which follow the freeway for its entire length.[27][28] I-5 continues along the east bank of the Columbia River, passing through Kalama on the way towards Longview and Kelso. At the south end of Kelso, near the confluence of the Columbia and Cowlitz rivers, the freeway intersects SR 432, which connects to Longview and the Lewis and Clark Bridge via SR 433. I-5 continues north along the Coweeman River to the Three Rivers Mall, located east of downtown Kelso, where SR 4 terminates.[25] Between Vancouver and Kelso, the highway is part of the Lewis and Clark Trail, a state scenic highway that continues west along SR 4 towards the Pacific Ocean.[9][29]

The freeway continues north, following the Cowlitz River to Castle Rock, where it meets SR 411 and SR 504, the main highway to Mount St. Helens. North of Castle Rock, I-5 leaves the Cowlitz River and enters Lewis County, intersecting SR 506 west of Toledo and SR 505 east of Winlock. Between the two interchanges is the Gospodor Monument Park, a roadside attraction with four sculptures of up to 100 feet (30 m) in height commemorating religious and indigenous figures.[30] After their installation in 2002, the sculptures caused backups on the freeway due to rubbernecking by passing drivers who slowed down near them.[31][32] Near Napavine, I-5 becomes concurrent with US 12, which continues east across White Pass to Yakima.[9][25]

The two highways intersect SR 508 and cross over the Newaukum River near the Uncle Sam billboard, a politically conservative message board and roadside attraction.[33] I-5 and US 12 turn northwest to follow the river and passes along the western edge of Chehalis, where they intersect SR 6. After passing the Chehalis-Centralia Airport, the freeway follows the Chehalis River to the western side of Centralia. I-5 and US 12 then intersect SR 507 and gain a set of collector–distributor lanes as the freeway crosses the Skookumchuck River and a set of railroad tracks on the northwest side of the city. US 12 leaves the concurrency at Grand Mound, heading west towards Aberdeen while I-5 continues north into Thurston County.[9][25]

South Sound region

.jpg)

North of Grand Mound, I-5 passes two interchanges with SR 121, which forms a loop between two of the exits to serve Millersylvania State Park. The freeway travels through the suburb of Tumwater, passing the Olympia Regional Airport and several state office parks before reaching the terminus of US 101, a major highway that encircles the Olympic Peninsula, on the south side of Capitol Lake.[9] After the interchange, I-5 enters Olympia and turns eastward after passing the Washington State Capitol campus and downtown Olympia. The freeway runs through Lacey and the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge towards DuPont on the east side of the Nisqually River in Pierce County.[25]

Immediately east of DuPont, I-5 travels through Joint Base Lewis–McChord, a major military installation that encompasses land on both sides of the freeway and its parallel railroad. Near American Lake, an interchange with Thorne Lane marks the proposed western terminus of SR 704, a new highway that would travel between the boundaries of Fort Lewis and McChord Air Force Base (the two components of Joint Base Lewis–McChord) to Spanaway.[34] Continuing past the bases, I-5 passes through Lakewood and intersects SR 512 before it reaches Tacoma.[25]

In Tacoma, the freeway passes the Tacoma Mall, turns east, and splits into collector–distributor lanes that run through central Tacoma and serve two interchanges: the terminus of SR 16, which continues northwest over the Tacoma Narrows Bridge to the Kitsap Peninsula; and I-705 and SR 7, which serve downtown Tacoma, the Tacoma Dome, Tacoma Dome Station, and the Pacific Avenue corridor.[35] East of the Tacoma Dome area, I-5 intersects SR 167 and crosses over the Puyallup River and a railroad carrying Sounder commuter trains. The freeway reaches Fife on the Puyallup Indian Reservation and intersects SR 99, a section of former US 99, at 54th Avenue East near the Emerald Queen Casino. After crossing Hylebos Creek, I-5 turns north and ascends from the Puyallup River Valley, entering King County and the city of Federal Way while parallel to SR 99.[25]

After passing under SR 161 at Kitts Corner near the Wild Waves Theme Park, I-5 intersects SR 18, a freeway that connects to Auburn and Maple Valley. I-5 continues north past the former Weyerhauser headquarters campus to central Federal Way, where the freeway's high-occupancy vehicle lanes (HOV lanes) have a direct off-ramp to the Federal Way Transit Center and The Commons at Federal Way shopping mall. The freeway travels north into western Kent, intersecting SR 516 near Highline College. North of Angle Lake, I-5 tracks eastward between the cities of SeaTac and Tukwila, passing east of Seattle–Tacoma International Airport. At the Westfield Southcenter shopping mall in Tukwila, I-5 intersects SR 518, the primary means of access to the airport and Burien, and I-405, the eastern freeway bypass of Seattle that travels through Renton and the Eastside. The interchange includes several left-hand ramps, necessitating the separation of the thru HOV lanes from the mainline.[36] For a short distance, the light rail tracks of Central Link, which followed SR 518 from Tukwila International Boulevard station, join I-5 and run on its west side until the next interchange at SR 599, a short freeway that connects to SR 99.[37] From the SR 599 interchange, I-5 makes a gradual turn to the northwest while crossing over the Duwamish River and a mainline railroad, following the latter into the city of Seattle after an interchange with SR 900.[9][25]

Seattle and Shoreline

After entering Seattle, I-5 passes under the Central Link tracks at Boeing Access Road and runs northwesterly between Boeing Field and Georgetown to the west along the railroad and Beacon Hill to the east.[38] Mid-way along Beacon Hill near Jefferson Park, the freeway turns due north and intersects the east end of the Spokane Street Viaduct, part of the West Seattle Bridge, which has additional ramps to the SoDo area and the VA Puget Sound Medical Center.[25] I-5 continues north between SoDo and northern Beacon Hill, crossing over the western portal of the Beacon Hill light rail tunnel near Central Link's railyard and operating base.[39] At the north end of SoDo and Beacon Hill, I-5 intersects I-90, the state's major east–west freeway, forming a large interchange with ramps to T-Mobile Park and CenturyLink Field, the city's two sports stadiums.[9][25]

North of the interchange, I-5 travels on an elevated viaduct over the International District and splits into collector–distributor lanes that serve exits to Downtown Seattle. The thirteen-lane freeway, among the widest in the United States,[40] runs in the full block between 6th and 7th avenues between downtown to the west and First Hill to the east, home to Harborview Medical Center and Yesler Terrace. It passes to the east of Seattle's tallest building, the Columbia Center,[41] and the city's Central Library before adding a set of reversible express lanes in the median near Madison Street.[25] I-5 turns northeasterly and passes under two structures built atop sections of the highway: Freeway Park, a landscaped city park between Seneca and Union streets; and the Washington State Convention Center between Union and Pike streets.[42][43][44]

I-5 continues north out of downtown Seattle, passing 20 to 30 feet (6.1 to 9.1 m) under a retaining wall along Melrose Avenue at the edge of Capitol Hill.[45] To the west is the South Lake Union and Cascade neighborhoods, accessed via ramps to Stewart Street and Mercer Street. The freeway travels along the north end of Capitol Hill through the Eastlake neighborhood on the east side of Lake Union, passing over the I-5 Colonnade mountain bike park.[46] At Roanoke Park, I-5 intersects the western terminus of SR 520, a major freeway that crosses Lake Washington on the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge to Bellevue and Redmond.[25] The heavily trafficked Mercer Street and SR 520 exits use ramps that are on opposite sides of the freeway, causing vehicles to weave across several lanes that contributes to traffic congestion.[47][48] I-5 continues onto the Ship Canal Bridge towards the University District, crossing 160 feet (49 m) over a section of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and Eastlake Avenue parallel to the University Bridge. The bridge also includes a lower deck for the express lanes, with a ramp connecting to Northeast 42nd Street in the University District.[49][50]

I-5 runs north along 5th Avenue through the University District, a few blocks west of the University of Washington campus, and intersects Northeast 45th and 50th streets using a weaved pair of diamond interchanges.[51] In the Roosevelt–Green Lake area, I-5 intersects Ravenna Boulevard and SR 522, a major highway that travels along the north side of Lake Washington.[9] It also passes over a disused fallout shelter constructed beneath a berm near Northeast 68th Street.[52] Further north, the freeway reaches Northgate and the express lanes merge back with the mainline, forming a set of HOV lanes.[53] I-5 passes to the west of Northgate Mall and the Northgate light rail station along 1st Avenue before moving back east to 5th Avenue near Haller Lake.[54] At Jackson Park, freeway intersects SR 523, which runs on 145th Street and forms the northern city limit of Seattle. The interchange includes a set of flyer stops that are connected to SR 523 by a northbound loop ramp and southbound slip ramp.[55] I-5 continues north through Shoreline, passing the King County Metro north bus base and several suburban neighborhoods before reaching Snohomish County.[25]

Snohomish County

At the county line near Lake Ballinger, I-5 also intersects SR 104, a highway that connects to Lake Forest Park, Edmonds, and the Kitsap Peninsula via the Edmonds–Kingston ferry.[9] The freeway continues through western Mountlake Terrace, passing the Mountlake Terrace Transit Center and its median bus station near 236th Street Southwest. Upon entering Lynnwood, I-5 turns northeast and follows the Interurban Trail, passing the Lynnwood Transit Center, which is connected to the HOV lanes via a set of direct ramps.[56] Near the Lynnwood Convention Center, the freeway intersects SR 524 on 196th Street Southwest and its spur route on 44th Avenue West, and travels along the south side of the Alderwood Mall. To the east of the mall, I-5 intersects I-405 and SR 525.[25]

I-5 crosses into northern Lynnwood and intersects 164th Street Southwest near Martha Lake and Mill Creek, where a partial HOV ramp connects to the Ash Way Park and Ride.[57] The freeway continues north into Everett and intersects SR 96 southeast of Paine Field. It then passes Silver Lake and the South Everett park and ride (located in the freeway's median) at 112th Street Southeast near the Everett Mall and a southbound-only rest area.[58][59] Northeast of the mall, I-5 comes to a major interchange with several highways: SR 99, which travels southwest as Everett Mall Way; SR 526, which travels west to the Boeing Everett Factory and Mukilteo; SR 527, which travels south through Mill Creek; and Broadway, which continues north into downtown Everett.[9][60] From the mall interchange, I-5 descends towards the Lowell area on the east side of a hill with several suburban neighborhoods. Near the Everett Memorial Stadium and Lowell Park, the freeway intersects 41st Street in a single-point urban interchange, with additional ramps from the HOV and mainline lanes towards downtown Everett on Broadway.[61][62]

I-5 then curves northeasterly around downtown Everett, following the general course of the Snohomish River, and intersects the southern terminus of SR 529 at a half-diamond interchange with Pacific Avenue and Maple Street near the Everett train station and transit center. One block north of the interchange, the freeway intersects US 2, a major highway that travels across Stevens Pass to eastern Washington.[9] To the north of the US 2 ramps is a second half-diamond interchange with SR 529 Spur on Everett Avenue, at which point the HOV lanes terminate and leave the freeway at six total lanes.[63][64] I-5 continues north through a narrow trench in the Riverside neighborhood and passes Summit Park, a city park built using leftover land and excavated dirt from the freeway's construction.[25][65]

The freeway crosses the Snohomish River and descends into the river's estuary, which has several sloughs that I-5 crosses.[66] It also passes the Everett Water Pollution Control Facility and several wastewater treatment ponds, which produces strong odors that are noted by motorists.[67] On the north side of Steamboat Slough, I-5 turns northwesterly and intersects SR 529 before crossing over the BNSF Railway and Ebey Slough into Marysville. Within Marysville, the freeway runs due north along the boundary between the city and the Tulalip Indian Reservation and intersects several arterial streets:[68] SR 528 west of downtown Marysville, 88th Street near Quil Ceda Village, and 116th Street near the Tulalip Resort Casino and Seattle Premium Outlets shopping mall.[25][69]

North of the city and reservation, I-5 crosses over the railroad and enters Arlington's Smokey Point neighborhood, where it intersects SR 531 just west of Arlington Municipal Airport. A pair of rest areas are situated north of the interchange and are the busiest in the state, receiving 2.1 million visitors per year, and is home to a 22-foot-wide (6.7 m) Western red cedar stump that was once hollowed out to allow vehicles to drive through it.[70][71] The area around the freeway transforms from suburban to rural, with rolling hills and forested areas, as it approaches Island Crossing and an interchange with SR 530 west of downtown Arlington. North of Island Crossing, I-5 crosses the Stillaguamish River and passes the Stillaguamish Indian Reservation and the Angel of the Winds Casino Resort. The freeway continues northwest through rural Snohomish County and intersects SR 532 east of Stanwood before crossing into Skagit County.[25]

Skagit and Whatcom counties

From the Snohomish County line, the freeway turns north and descends into the Skagit Valley from Conway Hill, following the Skagit River that runs to its west. At Conway, I-5 intersects SR 534 and is joined by the BNSF railroad while continuing north towards Mount Vernon. The freeway narrows to four lanes within Mount Vernon and forms the boundary between the uphill suburban neighborhoods and downtown along the river. In downtown Mount Vernon, it intersects SR 536 in an interchange adjacent to the city's train station. At its next interchange, I-5 crosses the railroad and encounters SR 538, which connects the freeway to the Skagit Valley College and a minor retail corridor.[25] The freeway then crosses the Skagit River into Burlington on a bridge that partially collapsed on May 23, 2013, and was subsequently renamed the Trooper Sean M. O'Connell Jr. Memorial Bridge after a state trooper who died while directing detour traffic during its rebuilding.[72][73]

On the north side of the river, I-5 skirts the western edge of Burlington, passing car dealerships and retail stores, including the Cascade Mall and an outlet mall.[74][75] To the west of downtown Burlington, the freeway intersects SR 20, a major state highway, in a partial cloverleaf interchange that includes several businesses inside the western loop.[76] SR 20 continues west towards Anacortes and the Olympic Peninsula, and east through North Cascades National Park to the Okanogan Country as the North Cascades Highway. In northern Burlington, I-5 intersects the southern end of SR 11, which provides access to the western Chuckanut Mountains.[9] I-5 crosses the railroad and the Samish River before reaching the Skagit Casino Resort and Skagit Speedway near Bow and Alger, located in the middle of the heavily forested Chuckanut foothills. The freeway then travels up into the Chuckanut Mountains and crosses into Whatcom County south of Lake Samish.[25] The entire Skagit County section of I-5 was designated by the state legislature as the Skagit Valley Agricultural Scenic Corridor, a state scenic byway, recognizing its agricultural industry.[77]

I-5 travels along the eastern shore of Lake Samish before turning west to follow Chuckanut Creek through a narrow valley formed by Chuckanut and Lookout mountains in Lake Samish State Park. At Lake Padden, it turns north and enters the city of Bellingham, intersecting SR 11 east of Fairhaven and the Alaska Marine Highway terminal.[9] The freeway travels along the east side of Sehome Hill and downtown, passing the Western Washington University campus and several intersections with downtown streets. Northeast of downtown Bellingham, I-5 intersects SR 542 (the Mount Baker Highway) and turns west to meet SR 539 at the Bellis Fair Mall. The freeway heads northwest and leaves Bellingham after passing Bellingham International Airport, entering the predominately rural part of the Fraser Lowland region.[78] I-5 continues northwest along the railroad, crossing the Nooksack River on a pair of truss bridges near downtown Ferndale and reaching a junction with SR 548 north of the city. SR 548 continues along the highway and travels west towards the Cherry Point Refinery and Birch Bay.[25][79]

In Blaine, the northernmost city on I-5, SR 543 splits off to serve an alternate border crossing for trucks and freight.[80] I-5 travels along the northeast edge of downtown Blaine and intersects SR 548 before it reaches the Canadian border at the Peace Arch, where the highway terminates.[25][81] The monument was built in 1921 and its surrounding park is open to the public without needing to report to customs officers.[82] The park is connected to its administrative buildings and parking lots by a set of crosswalks across the northbound and southbound lanes of Interstate 5.[81] The Peace Arch–Douglas crossing is the westernmost on the mainland border and third-busiest,[81] with an average of 3,500 to 4,800 vehicles crossing per day.[83] The highway continues north as Highway 99 towards Vancouver, located 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Blaine.[84]

Seattle express lanes

I-5 has 7.14 miles (11.49 km)[1] of reversible express lanes within Seattle, which carry traffic in the peak direction on weekdays. The express lanes run in the median of the freeway between Downtown Seattle and Northgate, carrying 54,000 of the 270,000 vehicles on the Ship Canal Bridge on an average weekday, as measured in 2010.[85] The express lanes split from I-5 near James Street, with ramps to the mainline near the northbound Seneca Street exit; the southernmost downtown exit is at 5th Avenue and Cherry and Columbia streets under the Seattle Municipal Tower and adjacent to Seattle City Hall.[86][87]

The express lanes run through downtown and the Cascade neighborhood on the lower deck of I-5's southbound lanes, with ramps to the Pike Street at 9th Avenue (including a former exit to Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel's Convention Place station), and Stewart and Howell streets at Eastlake Avenue.[88][89] After the ramps from Mercer Street, the four-abreast express lanes emerge onto the median of I-5, following it past Capitol Hill and Eastlake to the Ship Canal Bridge. The express lanes cross the Ship Canal on the lower deck of the bridge, which includes an exit to Northeast 42nd Street in the University District. A southbound-only, HOV-only onramp from Ravenna Boulevard and an additional ramp to SR 522 connect the express lanes to North Seattle, leaving two express lanes and an HOV lane. The express lanes end southwest of the Northgate Mall, with a ramp to Northeast 103rd Street and the two remaining lanes merging onto I-5.[25][88] The downtown entrances at Cherry, Columbia, and Pike streets are designated for HOV use only to encourage carpooling without impacting buses using the ramps.[90][91][92]

The express lanes typically carry southbound traffic from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m. and northbound traffic from 11:15 a.m. to 11 p.m. on weekdays, with an overnight closure from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. On most weekends, the lanes are open to southbound traffic from 8 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. and northbound traffic from 1:45 p.m. to 11 p.m., with an overnight closure to reduce neighborhood noise.[93] The weekend times are sometimes adjusted for special events, including weekend sporting events, or construction on the mainline lanes in Seattle.[94] The express lanes are controlled by a series of movable gates and electronic signs controlled by a remote operations center that relies on CCTV cameras and an inspection and sweep for abandoned vehicles by a ground crew, who also set up safety nets during the 15-minute switch-over.[95][96] Prior to a $6.6 million project to automate the gates and signage in 2012, the switch-over took 50 minutes in total.[95][97]

Express lane exit list

The entire highway is in Seattle, King County.

| mi[1] | km | Destinations | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 165.29 | 266.01 | South end of express lanes | |||

| 165.62 | 266.54 | 5th Avenue, Columbia Street | Southbound exit and northbound entrance (HOV only) | ||

| 166.49 | 267.94 | Pike Street | Southbound exit and northbound entrance (HOV only) | ||

| 166.63 | 268.16 | Stewart Street – Seattle City Center | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 167.20– 167.26 | 269.08– 269.18 | Mercer Street | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 168.96 | 271.91 | Northeast 42nd Street – University of Washington | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 169.66 | 273.04 | Ravenna Boulevard | Southbound entrance only (HOV only) | ||

| 170.54 | 274.46 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| 172.07 | 276.92 | Northeast 103rd Street, 1st Avenue Northeast | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 172.43 | 277.50 | North end of express lanes | |||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

History

Early state and national highways

.svg.png)

The Pacific Highway was formed in 1913 by the state government as the north–south trunk in its first highway system, following the general route of modern-day I-5.[98] The trunk route, one of three suggested by good roads activists for several years and studied by the state legislature in 1909,[98][99] strung together several wagon trails dating back as early as the 1840s, when settlers arrived in the Puget Sound region from the Willamette Valley via the Cowlitz Trail.[100] Part of the highway also followed the military road constructed in the 1850s from Fort Vancouver to Fort Bellingham.[101]

The Washington section was part of a longer highway along the West Coast from Canada to Mexico, which was conceived by the Pacific Highway Association of North America in 1910.[102] The Pacific Highway was dedicated by 60,000 people at the Peace Arch in Blaine on September 4, 1923, with only a few sections still under construction.[98] Earlier that year, the Washington state government had designated it as State Road 1 and allotted funds to pave some rural sections. By 1925, almost all of the highway had been paved or improved to modern standards.[98][103]

The federal government and the American Association of State Highway Officials established a national highway system in 1926, designating most of the Pacific Highway north of Los Angeles as part of U.S. Route 99 (US 99).[104] The highway's Washington segment would ultimately be completed four years later with the opening of several bridges between Everett and Marysville.[98] It was also realigned in several areas to use newer cut-off roadways, bypassing older sections. The section between Burlington and Bellingham, historically on the water-facing Chuckanut Drive, was moved inland via Lake Samish in 1931.[105][106] State Road 1 was re-designated in 1937 as Primary State Highway 1 under the state's new highway numbering system, but was not signed to give priority to the overlapping US 99.[107][108] By 1941, the Pacific Highway was the busiest road in the Pacific Northwest and had been widened to four lanes in most urban areas due to traffic congestion, necessitating studies into by-passing cities along the corridor.[109][110]

State upgrades and Interstate planning

The federal government began planning for a national "superhighway" system in the late 1930s, including the US 99 corridor as the main route along the West Coast.[111] The highway system, designed with a minimum of four lanes in rural areas and strict grade separation, was approved for limited funding by Congress in 1944 and planned by the Bureau of Public Roads over the following years. The US 99 corridor was included in the initial 37,700-mile (60,672 km) system announced three years later by the Public Roads Administration.[112]

The state legislature adopted its own set of standards for limited-access highways in 1947, later amending them to encourage upgrades to existing two-lane roadways.[113] In 1951, the legislature authorized a $66.7 million bond issue to fund upgrades to US 99, including four-lane sections on all but 40 miles (64 km) of the highway and a modern "freeway" through Vancouver.[114] The plan was opposed by Governor Arthur B. Langlie, who questioned its constitutionality on the basis that it could violate the state constitution's 18th amendment. The bond's use of hedging against future gas tax revenues would, under some interpretations, not apply under the amendment's restriction of using the tax for highway purposes rather than paying off debts.[115] Later that year, the state supreme court upheld the legislature's authorization and allowed the program to move forward.[116] A separate bill in 1953 authorized planning for a toll highway between Tacoma and Everett to replace the nearly-complete Alaskan Way Viaduct and other urban streets with grade crossings and six total interchanges.[117][118]

The upgrade program was divided into 226 miles (364 km) of four-lane highway and 47 miles (76 km) of two-lane highway in rural sections between Marysville and Blaine.[119] Construction on the rural sections in southwestern Washington began in late 1951 and the first section near Kalama was opened early the following year.[120][121] Major bypasses of Centralia, Fort Lewis, Kelso, Marysville, and Tumwater were completed in 1954.[122][123][124] The 2-mile-long (3.2 km) Vancouver freeway opened on April 1, 1955, constituting the state's first grade-separated freeway and costing $7 million to construct.[125] In December 1955, the section between Chehalis and Olympia was moved onto a straighter highway that bypassed Tenino and other small towns along the meandering route of the Pacific Highway. Its opening marked the end of the southern section of the upgraded US 99.[126][127] The northern section was declared complete after a bypass of Mount Vernon and Burlington, including a major bridge over the Skagit River, was opened to traffic in June 1957.[128]

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on June 29, 1956, formally authorized the creation and majority-federal funding of the Interstate Highway System.[112] A few months later, the state supreme court overturned the $194 million authorization to build the 65-mile (105 km) Tacoma–Everett expressway as a toll road after finding it to be unconstitutional. The federal contribution under the Interstate Highways program was anticipated to be $165 million, but come in smaller installments that would require more time to complete the freeway project.[129] The entire US 99 corridor was subsequently assigned the designation of "Interstate 5" in 1957 and the federal government allocated planning funds to begin engineering of the Seattle Freeway,[130] which commanded its own Highway Department division.[118][131]

Interstate construction

Washington was the fastest of the three West Coast states to upgrade sections of US 99 to four lanes and partial Interstate standards using new interchanges, with only 15 miles (24 km) of the highway in northern Whatcom County still two-laned by 1959.[132] Among the first projects to use federal funding from the 1956 act was an upgrade of the Fort Lewis highway to four-lane freeway standards, which opened in September 1957 and included the relocation of the military base's main gate to a new cloverleaf interchange.[133][134] Another early Interstate project, the 6.5-mile (10.5 km) Olympia Freeway, was opened to traffic on December 12, 1958, at a cost of $11.6 million. It also included a freeway section of US 101 and US 410 that intersected I-5 in the state's first three-level interchange.[135] A rural section of freeway between Marysville and Mount Vernon was completed in early 1959.[136]

The first section of the Tacoma–Seattle–Everett freeway was opened to traffic on October 1, 1959, extending the Fort Lewis freeway 5 miles (8.0 km) from Gravelly Lake near McChord Field to South 72nd Street in southern Tacoma. The $4.68 million project built the six-lane freeway and a cloverleaf interchange at SSH 5G (now SR 512).[137][138] The Tacoma section was also the first to use the Interstate highway shield, which was installed during construction in 1958.[139] By the end of 1959, new interchanges and overpasses had brought most of the highway between Vancouver and Olympia to Interstate standards.[140] Governor Albert D. Rosellini announced an accelerated push for freeway construction, primarily aimed at completing Interstate 5 between Seattle and the Canadian border, in August 1960.[141]

The 19.7 miles (31.7 km) section between north Seattle and Everett was opened on February 3, 1965. It was constructed over sections of the former Seattle–Everett Interurban Railway and cost $23 million.[142] Several of the freeway's interchanges in southern Snohomish County were opened at a later date.[143] The final section of I-5, also in Snohomish County, was opened on May 14, 1969, between Everett and Marysville.[144] The stretch of I-5 from Marysville to Mount Vernon was already opened as a four-lane divided highway without overpasses.[145] Several right-in/right-out intersections and lower-quality sections remained, however, until the completion of several widening projects in the 1970s.[146]

Seattle planning and construction

A municipal traffic plan from 1946 outlined designs for a north–south freeway through Seattle that was later refined into the early concepts for Interstate 5 in the 1950s.[147] A design from 1954 proposed an eight-lane facility from Downtown Seattle to Ravenna that would cost $194 million to construct.[148] Alternate plans would have placed the freeway further east on 12th Avenue in Capitol Hill or along Empire Way, which would later be used for the proposed R. H. Thomson Expressway.[149] A larger, twelve-lane freeway through Downtown Seattle with a reversible express lane system was announced in April 1957 ahead of a series of public hearings.[150] The proposal received a mix of strong support and criticism from members of the public, while the city government endorsed the plan with a caveat that right of way along the freeway be reserved for use by rapid transit.[151][152] The twelve-lane design, sans transit, was approved the following year by the Bureau of Public Roads, allowing for property acquisition to begin.[153][154][155] A dedicated office was created to handle property acquisition, which would require 4,500 parcels of land, and 10 percent were condemned by the government.[156][157]

.jpg)

The first section of the freeway within Seattle to be built was the Ship Canal Bridge, a double-decker bridge over the Lake Washington Ship Canal between the University District and Eastlake, which began construction in August 1958.[158] The bridge and 2.2 miles (3.5 km) of freeway on the north and south ends between Ravenna Boulevard and Roanoke Park were dedicated and opened to traffic on December 18, 1962. The bridge cost $14 million to construct and was among the largest ever built in the Pacific Northwest.[159][160] Construction of the freeway through Downtown Seattle was delayed after 100 citizens marched on June 1, 1961, in protest of the "trench" design and sought to add a lidded tunnel with a rooftop park.[161][162] The proposed design change was deferred for later consideration, but delayed the start of construction to the following year.[163]

The construction of I-5 through Downtown Seattle and First Hill necessitated the demolition of significantly developed areas and cut off walking commutes, who "were by far the most vociferous critics of the proposed route,"[164] but far from the only ones. Architect Paul Thiry said in the early 1970s, "It was with the Freeway, cutting through the very heart of the city, that Seattle began taking one of its wrong turns and started to lose its identity as a city." He proposed a lid extending from Columbia Street north to Olive Way, roughly the entire length of downtown.[165]

Among the buildings torn down in the Downtown-First Hill area to build the freeway was the Hotel Kalmar at Sixth Avenue and James Street (built 1881 as the Western Hotel, demolished 1962), the last of Seattle's pioneer-era hotels, predating the Great Seattle Fire,[166][167] and Seattle's then-oldest public building, the Seventh Avenue Fire Hall (built 1890, demolished c. 1962).[164]

The Seattle portion of the freeway, including the southern approach from Tukwila, was completed on January 31, 1967.[168]

In the years since the freeway's construction, Seattle has made several efforts to stitch back together pedestrian routes disrupted by the freeway, achieving part of Thiry's proposed "lid". The most visible of these efforts are Freeway Park (opened 1976), built as a lid over the freeway and connecting Downtown to First Hill, and the Washington State Convention and Trade Center (built 1982-1988) adjacent to Freeway Park, also bridging the freeway.[164] The 7.5-acre (30,000 m2) I-5 Colonnade mountain bike park (opened 2007) uses the freeway as a roof and reconnects Eastlake to Capitol Hill.[169]

Major projects and incidents

In the 1990s and early 2000s, several major windstorms brought floods that inundated and temporarily shut down sections of I-5 between Kelso and Centralia. Major floods in November 1990, February 1996, December 2007, and January 2009 resulted in days-long closures and required minor repairs to the road and other structures before re-opening to traffic.[170][171] The December 2007 flood closed a 20-mile (32 km) section of the interstate between Chehalis and Grand Mound for four days and required further repairs.[172][173]

On May 23, 2013, the northernmost span of the Skagit River bridge between Mt. Vernon and Burlington collapsed after being struck by an oversize semi-trailer truck.[174] The bridge's collapse triggered a state of emergency and a temporary bridge was installed a month later.[175] The temporary bridge was replaced with a permanent replacement in September 2013.[176]

On December 18, 2017, an Amtrak Cascades train derailed onto the southbound lanes of I-5 near DuPont, causing it to be blocked for several hours. The train was the first trip on the new Point Defiance Bypass route, constructed along the freeway between Nisqually and Tacoma Dome Station.[177]

Planned improvements

The Vancouver section of I-5 was planned to rebuilt as part of the Columbia River Crossing program, which would have replaced the six-lane Interstate Bridge with a wider bridge at a cost of approximately $3.4 billion. The northern approach to the bridge would have included a collector–distributor system with a maximum width of 16 lanes. The program was cancelled in 2013 after $175 million had been spent planning due to opposition within the Washington state legislature, but the bridge proposal has been revived several times since.[178] As of 2018, elected officials from Washington are attempting to convince counterparts in Oregon to an agreement that would replace the bridge.[179]

Within the Seattle region, preservation and maintenance of I-5 is expected to cost $2.5 billion between 2020 and 2040, and substantial rebuilding of the freeway will be required.[180][181] Portions of the freeway's right-of-way will be used for extensions of Sound Transit's Link light rail system, which is planned to extend north to Lynnwood and south to Federal Way by 2024.[182][183] As part of the reconstruction of SR 520, a new HOV ramp from the I-5 reversible lanes to SR 520 is planned to be opened in 2023, alongside a fifth reversible lane for HOV that extends south to Mercer Street.[184][185]

The 2015 Connecting Washington transportation funding package includes allocations for several new and reconstructed interchanges along I-5 in Lacey and Marysville. The SR 510 interchange in Lacey is planned to be reconstructed into the state's first diverging diamond interchange and is scheduled to be opened in 2020.[186] The SR 529 interchange in southern Marysville is planned to be expanded into a full interchange,[187] while a new interchange at 156th Street is scheduled to open in the late 2020s.[188][189]

The city government of Seattle has studied the expansion of lids and caps over sections of I-5 in Downtown Seattle to create new urban park spaces and for other uses, based on grassroots support for the concept.[190]

Exit list

| County | Location | mi[1] | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia River | 0.00 | 0.00 | — | Continuation into Oregon | ||

| Interstate Bridge | ||||||

| Clark | Vancouver | 0.41 | 0.66 | 1A | ||

| 0.45 | 0.72 | 1B | 6th Street – Vancouver City Center | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 1.05 | 1.69 | 1C | ||||

| 1.58 | 2.54 | 1D | 4th Plain Boulevard | |||

| 2.35 | 3.78 | 2 | ||||

| 3.07 | 4.94 | 3 | Northeast Highway 99, Main Street | |||

| | 4.36 | 7.02 | 4 | Northeast 78th Street | ||

| | 5.39 | 8.67 | 5 | Northeast 99th Street | ||

| | 7.24 | 11.65 | 7A | Northeast 134th Street – Washington State University Vancouver | Northbound exit and southbound entrance; southbound exit is via I-205 (exit 36) | |

| | 7.47 | 12.02 | 7B | Northeast 139th Street | No southbound exit | |

| | 7.50 | 12.07 | 7 | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| | 9.51 | 15.30 | 9 | Northeast 179th Street – Clark County Fairgrounds | ||

| | 11.20 | 18.02 | 11 | |||

| Ridgefield | 14.21 | 22.87 | 14 | |||

| | 16.80 | 27.04 | 16 | NW La Center Road - La Center, Cowlitz Reservation | ||

| Cowlitz | Woodland | 21.08 | 33.92 | 21 | ||

| 22.72 | 36.56 | 22 | Dike Access Road | |||

| | 27.70 | 44.58 | 27 | Todd Road – Port of Kalama | ||

| Kalama | 29.84– 30.64 | 48.02– 49.31 | 30 | Kalama | ||

| | 32.28 | 51.95 | 32 | Kalama River Road | ||

| Kelso | 36.97 | 59.50 | 36A | Kelso Drive | No southbound exit | |

| 36.97 | 59.50 | 36 | Talley Way – Kelso Industrial Area | Signed as exits 36B northbound and 36A southbound | ||

| 36.97 | 59.50 | 36 | ||||

| 39.88 | 64.18 | 39 | ||||

| 40.77 | 65.61 | 40 | ||||

| | 42.73 | 68.77 | 42 | Lexington Bridge Road | ||

| | 46.20 | 74.35 | 46 | Headquarters Road, Pleasant Hill Road | ||

| Castle Rock | 48.04 | 77.31 | 48 | |||

| 49.91 | 80.32 | 49 | ||||

| | 52.72 | 84.84 | 52 | Barnes Drive, Toutle Park Road | ||

| Lewis | | 57.41 | 92.39 | 57 | Jackson Highway, Barnes Drive | |

| | 59.27 | 95.39 | 59 | |||

| | 60.98 | 98.14 | 60 | |||

| | 63.49 | 102.18 | 63 | |||

| | 68.48 | 110.21 | 68 | South end of US 12 overlap | ||

| Napavine | 71.12 | 114.46 | 71 | |||

| 72.85 | 117.24 | 72 | Rush Road | |||

| Chehalis | 74 | Labree Road | ||||

| 76.62 | 123.31 | 76 | 13th Street | |||

| 78.04 | 125.59 | 77 | ||||

| 79.15 | 127.38 | 79 | Chamber Way | |||

| Centralia | 81.74 | 131.55 | 81 | Southbound exit is via exit 82 | ||

| 82.80 | 133.25 | 82 | Harrison Avenue, Factory Outlet Way | |||

| Thurston | | 88.40 | 142.27 | 88 | North end of US 12 overlap | |

| | 95.28 | 153.34 | 95 | |||

| | 99.35 | 159.89 | 99 | |||

| Tumwater | 101.37 | 163.14 | 101 | Tumwater Boulevard – Olympia Regional Airport | ||

| 102.86 | 165.54 | 102 | Trosper Road – Black Lake | |||

| 104.05 | 167.45 | 103 | Deschutes Way, 2nd Avenue | No southbound entrance | ||

| 104.39 | 168.00 | 104 | ||||

| Olympia | 105.52 | 169.82 | 105A | State Capitol, Olympia City Center | Signed as exit 105 northbound | |

| 105.82 | 170.30 | 105B | Port of Olympia | Signed as exit 105 northbound | ||

| 107.52 | 173.04 | 107 | Pacific Avenue | |||

| Lacey | 108.46 | 174.55 | 108A | Sleater–Kinney Road south | No northbound entrance; signed as exit 108 southbound | |

| 108.46 | 174.55 | 108B | Sleater–Kinney Road north | No northbound entrance; southbound exit is via exit 109 | ||

| 108.96 | 175.35 | 108C | College Street | Northbound exit only | ||

| 109.19 | 175.72 | 109 | Martin Way | |||

| 112.01 | 180.26 | 111 | ||||

| | 114.36 | 184.04 | 114 | Nisqually, Old Nisqually | ||

| Pierce | | 116.77 | 187.92 | 116 | Mounts Road – Old Nisqually | |

| DuPont | 118.02 | 189.93 | 118 | Center Drive - DuPont | ||

| 119.07 | 191.62 | 119 | Steilacoom–DuPont Road | |||

| | 120.93 | 194.62 | 120 | Joint Base Lewis–McChord | ||

| Lakewood | 122.74 | 197.53 | 122 | Berkeley Street | ||

| 123.64 | 198.98 | 123 | Thorne Lane | |||

| 124.70 | 200.69 | 124 | Gravelly Lake Drive | |||

| 125.92 | 202.65 | 125 | Bridgeport Way – McChord Field | |||

| 127.54 | 205.26 | 127 | ||||

| | 128.98 | 207.57 | 128 | South 84th Street | Southbound exit is via exit 129 | |

| Tacoma | 129.65 | 208.65 | 129 | South 72nd Street / South 74th Street | ||

| 130.75 | 210.42 | 130 | South 56th Street, Tacoma Mall Boulevard – University Place | |||

| 131.89 | 212.26 | 132 | ||||

| 133.76 | 215.27 | 133 | ||||

| 134.93 | 217.15 | 134 | Portland Avenue | Southbound exit is via exit 135 | ||

| 135.09 | 217.41 | 135 | ||||

| Fife | 136.15 | 219.11 | 136 | 20th Street East – Port of Tacoma | Signed as exits 136A (20th Street) and 136B (Port of Tacoma) northbound | |

| 137.51 | 221.30 | 137 | ||||

| King | Federal Way | 142.06 | 228.62 | 142 | Signed as exits 142A (east) and 142B (west) | |

| 143.89 | 231.57 | 143 | South 320th Street – Federal Way | |||

| 144.08 | 231.87 | — | South 317th Street | HOV only | ||

| Kent | 146.87 | 236.36 | 147 | South 272nd Street | ||

| 149.23 | 240.16 | 149 | Signed as exits 149A (east) and 149B (west) northbound | |||

| SeaTac | 151.24 | 243.40 | 151 | Military Road, South 200th Street | ||

| 152.32 | 245.14 | 152 | South 188th Street, Orillia Road South | |||

| Tukwila | 154.19 | 248.14 | 153 | Southcenter Parkway – Tukwila, Southcenter Mall | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |

| 154.46 | 248.58 | 154 | Signed as exits 154A (I-405) and 154B (SR 518) southbound | |||

| 154.71 | 248.98 | 154B | Southcenter Boulevard – Tukwila, Southcenter Mall | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 156.00 | 251.06 | 156 | ||||

| 157.40 | 253.31 | 157 | ||||

| 158.07 | 254.39 | 158 | Boeing Access Road, East Marginal Way, Airport Way | |||

| Seattle | 161.27 | 259.54 | 161 | Swift Avenue, Albro Place | ||

| 161.37– 161.60 | 259.70– 260.07 | 162 | Corson Avenue, Michigan Street | |||

| 163.03 | 262.37 | 163A | Columbian Way, West Seattle Bridge | Signed as exit 163 northbound | ||

| 163.54 | 263.19 | 163B | Forest Street, 6th Avenue South | Southbound exit only | ||

| 164.33 | 264.46 | 164 | Airport Way | Southbound exit only | ||

| 164.55 | 264.82 | 164A | Signed as exit 164 southbound; I-90 exits 2A-B eastbound, 2B-C westbound | |||

| 164.55 | 264.82 | 164B | 4th Avenue South / South Atlantic Street (SR 519) | Signed as exit 164 southbound | ||

| 164.68 | 265.03 | 164 | Dearborn Street | Signed as exit 164A northbound; no southbound entrance | ||

| 165.35 | 266.11 | — | Express Lanes | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 165.38 | 266.15 | 165A | James Street | Signed as exit 164A northbound | ||

| 165.63 | 266.56 | 164A | Madison Street – Convention Center | Northbound exit only | ||

| 165.75 | 266.75 | 165 | Seneca Street | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 165.81 | 266.85 | 165B | Union Street | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 166.26 | 267.57 | 166 | Olive Way | Northbound exit and entrance | ||

| 166.42 | 267.83 | 166 | Stewart Street, Denny Way | Southbound exit and entrance | ||

| 166.97 | 268.71 | 167 | Mercer Street – Seattle Center | |||

| 167.73 | 269.94 | 168A | Lakeview Boulevard | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 168.12 | 270.56 | 168B | ||||

| 168.18 | 270.66 | 168A | Boylston Avenue, Roanoke Street | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 168.40– 169.07 | 271.01– 272.09 | Ship Canal Bridge | ||||

| 169.44 | 272.69 | 169 | Northeast 45th Street | |||

| 169.69 | 273.09 | 169 | Northeast 50th Street | |||

| 170.31 | 274.09 | 170 | Ravenna Boulevard, Northeast 65th Street | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| 170.70 | 274.72 | 171 | Northeast 71st Street, Northeast 65th Street | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 170.87 | 274.99 | 171 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| 171.56 | 276.10 | 172 | North 85th Street, Aurora Avenue North (to SR 99), Northeast 80th Street | |||

| 172.58 | 277.74 | — | Express Lanes | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| 172.82 | 278.13 | 173 | 1st Avenue Northeast, Northgate Way | |||

| 173.89 | 279.85 | 174 | Northeast 130th Street, Roosevelt Way | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| Seattle–Shoreline city line | 174.64 | 281.06 | 175 | |||

| Shoreline | 175.58 | 282.57 | — | Metro Transit Base | Buses and transit vehicles only | |

| 176.19 | 283.55 | 176 | Northeast 175th Street – Shoreline | |||

| King–Snohomish county line | Shoreline–Mountlake Terrace city line | 177.81 | 286.16 | 177 | ||

| Snohomish | Mountlake Terrace | 178.33 | 286.99 | 178 | 236th Street Southwest – Mountlake Terrace | Northbound exit and southbound entrance |

| 179.35 | 288.64 | 179 | 220th Street Southwest – Mountlake Terrace | |||

| Lynnwood | 180.69 | 290.79 | — | 46th Avenue West (Lynnwood Transit Center) | HOV only | |

| 180.77 | 290.92 | 181A | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| 181.59 | 292.24 | 181B | Signed as exit 181 southbound | |||

| | 182.67 | 293.98 | 182 | |||

| | 182.67 | 293.98 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| | 183.96 | 296.05 | 183 | 164th Street Southwest | ||

| | 184.21 | 296.46 | — | Ash Way | Northbound exit and southbound entrance (buses only) | |

| | 186.49 | 300.13 | 186 | |||

| Everett | 187.80 | 302.23 | — | 112th Street Southeast | HOV only | |

| 189.37 | 304.76 | 189 | ||||

| 192.51 | 309.81 | — | Broadway | Northbound exit southbound entrance (HOV only) | ||

| 192.72 | 310.15 | 192 | 41st Street (to Evergreen Way), Broadway | |||

| 193.69 | 311.71 | 193 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| 193.98 | 312.18 | 194 | ||||

| 194.08 | 312.34 | 194 | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | |||

| 194.87 | 313.61 | 195 | Marine View Drive – Port of Everett | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | ||

| | 198.33 | 319.18 | 198 | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | ||

| Marysville | 199.17 | 320.53 | 199 | |||

| | 200.84 | 323.22 | 200 | 88th Street Northeast, Quil Ceda Way | ||

| | 202.52 | 325.92 | 202 | 116th Street Northeast | ||

| | 206.13 | 331.73 | 206 | |||

| Arlington | 208.72 | 335.90 | 208 | |||

| | 210.36 | 338.54 | 210 | 236th Street Northeast | ||

| | 212.71 | 342.32 | 212 | |||

| | 215.09 | 346.15 | 215 | 300th Street Northwest | ||

| Skagit | | 218.61 | 351.82 | 218 | Starbird Road | |

| | 221.13 | 355.87 | 221 | |||

| | 224.00 | 360.49 | 224 | Old Highway 99 South | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |

| Mount Vernon | 225.19 | 362.41 | 225 | Anderson Road | ||

| 226.45 | 364.44 | 226 | ||||

| 227.79 | 366.59 | 227 | ||||

| Burlington | 228.93 | 368.43 | 229 | George Hopper Road | ||

| 230.20 | 370.47 | 230 | ||||

| | 231.27 | 372.19 | 231 | |||

| | 232.89 | 374.80 | 232 | Cook Road – Sedro-Woolley | ||

| | 236.45 | 380.53 | 236 | Bow Hill Road – Bow, Edison | ||

| | 240.99 | 387.84 | 240 | Alger | ||

| Whatcom | | 242.92 | 390.94 | 242 | Nulle Road – South Lake Samish | |

| | 246.30 | 396.38 | 246 | North Lake Samish | ||

| Bellingham | 250.79 | 403.61 | 250 | |||

| 252.14 | 405.78 | 252 | Samish Way – Western Washington University | |||

| 253.03 | 407.21 | 253 | Lakeway Drive | |||

| 253.85 | 408.53 | 254 | Iowa Street, Ohio Street, State Street | |||

| 254.88 | 410.19 | 255 | ||||

| 256.27 | 412.43 | 256 | Signed as exits 256A (SR 539) and 256B (Bellis Fair-Mall Parkway) northbound | |||

| 257.04 | 413.67 | 257 | Northwest Avenue | |||

| | 257.72 | 414.76 | 258 | |||

| | 260.19 | 418.74 | 260 | Slater Road – Lummi Island | ||

| Ferndale | 262.63 | 422.66 | 262 | Main Street – Ferndale City Center | ||

| 263.52 | 424.09 | 263 | Portal Way | |||

| | 266.04 | 428.15 | 266 | |||

| | 270.30 | 435.01 | 270 | Birch Bay, Lynden | ||

| Blaine | 274.23 | 441.33 | 274 | Peace Portal Drive – Semiahmoo | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |

| 275.21 | 442.91 | 275 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |||

| 276.26 | 444.60 | 276 | ||||

| 276.62 | 445.18 | Canada – United States border at Peace Arch Border Crossing | ||||

| — | Continuation into British Columbia | |||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

References

- Multimodal Planning Division (February 26, 2014). "State Highway Log Planning Report 2013, SR 2 to SR 971" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. pp. 220–322. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "Table 1: Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System Of Interstate and Defense Highways as of December 31, 2017". Federal Highway Administration. December 31, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Official Route Numbering for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (Map). American Association of State Highway Officials, Public Roads Administration. August 14, 1957. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Weingroff, Richard F. (1996). "Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, Creating the Interstate System". Public Roads. Washington, D.C.: Federal Highway Administration. 60 (1). ISSN 0033-3735. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Dougherty, Phil (April 10, 2010). "Interstate 5 is completed in Washington state on May 14, 1969". HistoryLink. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Horton, Jeffery L. (November 2014). "Surviving An Interstate Bridge Collapse". Public Roads. Federal Highway Administration. 78 (3). Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- National Highway System: Washington (PDF) (Map). Federal Highway Administration. October 1, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "Transportation Commission List of Highways of Statewide Significance" (PDF). Washington State Transportation Commission. July 26, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Washington State Highways 2014–2015 (PDF) (Map). 1:842,000. Washington State Department of Transportation. 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2018, with inset maps.

- "The Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways: Part II – Mileage". Federal Highway Administration. December 31, 1997. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Hill, Christian (August 2, 2013). "I-5 in Washington becomes Purple Heart Trail to honor veterans". The Columbian. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- MacDonald, Douglas (May 15, 2013). "Trans-poor-tation 3: No high five for I-5". Crosscut.com. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Lewis, Mike (March 27, 2001). "I-5 drives population increase". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A1.

- Bacon, John; Farley, Josh (December 18, 2017). "6 dead after Amtrak Cascades train derails onto Interstate 5 near Tacoma". Statesman-Journal. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- "Passenger Rail in Washington". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- Gutman, David (June 19, 2017). "Can't Washington state ease I-5 traffic? Fixes exist, but most of them are pricey". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "2016 Annual Traffic Report" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. pp. 73–82. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Lindblom, Mike (February 5, 2018). "It's worse than you think: Everett leads the nation in traffic congestion, report says". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- "2017 Corridor Capacity Report" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. December 2017. pp. 11–14. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- Gutman, David (June 19, 2017). "Here's why I-5 is such a mess in Seattle area, and what keeps us moving at all". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- Dietrich, William (April 30, 2006). "Lynnwood Redux: Where else will 100,000 newcomers a year go now?". The Seattle Times. p. 16. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- Pesanti, Dameon (February 12, 2017). "Interstate Bridge turns 100: 'With Iron Bands,' a century spanned". The Columbian. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 1A/1B: Junction SR 14" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. June 9, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Downtown Vancouver Walking Map (PDF) (Map). City of Vancouver. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Google (June 14, 2018). "Interstate 5, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Florip, Eric (October 8, 2014). "Rest area rebuild expands Gee Creek site". The Columbian. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Passenger Rail System, Washington State (PDF) (Map). Washington State Department of Transportation. January 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 22: Junction Dike Access Road" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. October 12, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "Lewis and Clark Trail Scenic Byway". Washington State Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Richard, Terry (March 25, 2009). "I-5 eye catcher: Gospodor Monument at Toledo". The Oregonian. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Mittge, Brian (December 24, 2002). "Gospodor's monuments continue to affect traffic". The Chronicle. Centralia, Washington. p. A3.

- Anderson, Peggy (May 25, 2003). "Safety of motorists towers over debate about man's art". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. Associated Press. p. C9. Retrieved September 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kershaw, November 28, 2004. "Highway's Message Board Now Without a Messenger". The New York Times. p. 37. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- "SR 704 - Cross Base Highway Project". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Nunnally, Derrick (July 11, 2017). "Southbound I-5 will get local/express division in Tacoma". The News Tribune. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 154: Junction SR 405/SR 518" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. January 5, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Nowlin, Mark (July 12, 2009). "Your guide to riding light rail" (Map). The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Your ride to airport is on the way". The Seattle Times. November 24, 2006. p. A1.

- "Beacon Hill Tunnel & Station" (PDF). Sound Transit. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Urban Highways with the Most Lanes" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. July 27, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Duncan, Don (October 8, 1989). "Promises to keep: The sky's the limit". The Seattle Times. p. 13.

- Easton, Valerie (June 27, 2008). "In the concrete jungle, Freeway Park will offer respite once again". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Mahoney, Sally Gene (July 24, 1983). "Convention Center: Unveiled model gives a glimpse of how it may look". The Seattle Times. p. D6.

- "Final List of Nationally and Exceptionally Significant Features of the Federal Interstate Highway System" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. November 1, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Barber, Mike; Wong, Brad; Murakami, Kery (December 19, 2008). "Students screamed as bus crashed through I-5 barrier". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- McQuaide, Mike (September 25, 2008). "Flying high under I-5 at the new mountain bike park". The Seattle Times. p. H12. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Lindblom, Mike (February 8, 2018). "More traffic lights on Mercer Street: Ramp-metering signals coming to I-5 onramps". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Robinson, Herb (May 3, 1968). "Freeway 'Friction' Develops". The Seattle Times. p. A.

- Clarridge, Christine; Birkland, Dave (August 29, 2001). "A day of despair, anger on I-5 – Woman survives plunge; commute halted 3-1/2 hours". The Seattle Times. p. A1.

- Birkland, Dave; Nalder, Eric; Andrews, Paul (May 14, 1993). "Driver escapes dangling truck – with fiery cab hanging off I-5, trucker unhurt". The Seattle Times. p. C1.

- "SR 5 – Exit 169: Junction NE 45th Street/NE 50th Street" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. August 9, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Becker, Paula (August 9, 2010). "State of Washington breaks ground for a fallout shelter under the Seattle Freeway (Interstate 5) in Seattle's Ravenna neighborhood on May 15, 1962". HistoryLink. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Foster, George (October 21, 2001). "Getting There: Now you see the lane ..." Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Miller, Brian (November 8, 2017). "TOD proposals due for Northgate Station; city is seeking an upzone". Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 175: Junction SR 523/NE 145th Street" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. February 7, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- Hadley, Jane (November 16, 2004). "State opens direct-access ramps to I-5 at Lynnwood Transit Center". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 183: Junction 164th Street SW" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. August 29, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Nohara, Yoshiaki (September 12, 2008). "Soon, you'll be able to hop on a bus in the I-5 median". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Safety rest area locations". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 189: Junction SR 99/SR 526/SR 527" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. January 13, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 192: Junction 41st Street/Old SR 529/Broadway Avenue" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. July 20, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Nohara, Yoshiaki (September 30, 2008). "Everett finishing work on link to I-5". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 193/194: Junction Pacific Avenue/SR 2/SR 529" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. June 3, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "I-5 – Everett HOV Freeway Expansion Project" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. November 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- May, Allan; Preboski, Dale (1989). The History of Everett Parks: A Century of Service and Vision. Norfolk, Virginia: The Donning Company. p. 50. ISBN 0-89865-794-6. OCLC 20453314.

- "Snohomish River Estuary Recreation Guide". Snohomish County Parks and Recreation. 1999. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Tuinstra, Rachel (March 24, 2004). "Go ahead, take a deep breath". The Seattle Times. p. H13. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Tulalip Tribes Hazard Mitigation Plan 2010 Update, Section II: Community Profile" (PDF). Tulalip Tribes. August 2010. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 26, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Winters, Chris (November 25, 2015). "Bridge over I-5 enters final phases". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Whitley, Peyton (August 6, 2003). "Rest areas: I-5 asylums". The Seattle Times. p. H20. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Barr, Robert A. (July 5, 1970). "Marysville Stump Dates Back to Caesar". The Seattle Times. p. G5.

- Burton, Lynsi (May 23, 2014). "The Skagit River bridge, 1 year after collapse". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Long, Priscilla (September 16, 2013). "I-5 Skagit River Bridge at Mount Vernon collapses on May 23, 2013". HistoryLink. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Wanielista, Kera (March 4, 2016). "Burlington postpones marijuana zoning issue". Skagit Valley Herald. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Judd, Ron C. (December 26, 2003). "Burlington frets about its soul". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "SR 5 – Exit 230: Junction SR 20/Burlington/Anacortes" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. February 4, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Judd, Ron (April 21, 2013). "From wild birds to beet seeds, the Skagit Valley's riches are being kept safe". The Seattle Times. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- "Whatcom County Rural Land Study: A Collaborative Report Identifying Rural Areas of Agricultural Significance". Whatcom County. February 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "BP Cherry Point Revised Cogeneration Project Compensatory Mitigation Plan". BP. p. 21. Retrieved June 15, 2018 – via Google Books.

- "New signs show wait times at Canadian border". The Everett Herald. Associated Press. June 23, 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Peace Arch Port of Entry Redevelopment Draft Environmental Impact Statement". General Services Administration. November 28, 2005. p. 3-126. Retrieved June 15, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Dougherty, Phil (October 18, 2009). "Peace Arch Park (Blaine)". HistoryLink. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Heim, Kristi (February 9, 2009). "Border work at Peace Arch won't end in time for Olympics". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Peace Arch Land Port of Entry" (PDF). General Services Administration. June 23, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Lindblom, July 14, 2011. "State considers tolls for I-5 express lanes". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Lindblom, Mike (May 8, 2018). "Preparations for closure of transit tunnel lag". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- McDermott, Terry (May 7, 1989). "High-rise: Digging the hole – Latest skyscraper rises from one man's dream, another's financial pit". The Seattle Times. p. A1.

- "I-5 Express Lane Map". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- Guillen, Tomas (September 26, 1990). "Sign at bus tunnel can't always be believed". The Seattle Times. p. A1.

- "Hot line set against fast-lane cheaters". The Seattle Times. February 3, 1984. p. C16.

- Lane, Bob (February 28, 1977). "Carpoolers gain route; Access to express lanes". The Seattle Times. p. A7.

- Murakami, Kery (July 20, 2003). "Getting There: HOV exits are meant to discourage solo driving". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Express Lane Closures, Adjustments, Schedule Changes". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- "I-5 Express Lane Operation on Weekends". Washington State Department of Transportation. 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- "Drivers save time and money with automated I-5 express lanes" (Press release). Washington State Department of Transportation. July 23, 2012. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Whitely, Peyton (October 28, 1990). "I-5 express lanes built to prevent bottlenecks". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Lindblom, Mike (March 29, 2008). "Express-lane switch stuck in slow motion". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Caldbick, John (March 23, 2012). "Ebey Slough Bridge (1925-2012)". HistoryLink. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- "Good Roads Association Outlines Great Highways". Kennewick Courier. May 31, 1912. p. 3. Retrieved June 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Another Trail". Terre Haute Star. March 1, 1962. p. 8. Retrieved June 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- McDonald, Lucile (November 24, 1963). "Old Military Road Takes on a New Life". The Seattle Times. pp. 4–5.

- "Autoists Organize Highway Association". The Seattle Times. September 20, 1910. p. 9.

- Rand McNally Official 1925 Auto Trails Map of Washington and Oregon (Map). 1:1,077,120. Rand McNally. 1925. Retrieved July 25, 2018 – via David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

- Bureau of Public Roads; American Association of State Highway Officials (November 11, 1926). United States System of Highways Adopted for Uniform Marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). 1:7,000,000. Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey. OCLC 32889555. Retrieved November 7, 2013 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- "Samish, Skagit Highways Next, Humes Pledges". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. August 21, 1931. p. 10.

- "Chapter 36: Pacific Highway" (PDF). Session Laws of the State of Washington, 1931. Washington State Legislature. March 12, 1931. pp. 107–108. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "George Washington's Head to Mark State Highways". The Seattle Times. February 8, 1938. p. 13.

- "Chapter 190: Establishment of Primary State Highways" (PDF). Session Laws of the State of Washington, Twenty-Fifth Session. Washington State Legislature. March 17, 1937. p. 933–943. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- "Washington State Highways Traverse Scenic Wonderland". The Seattle Times. July 27, 1941. p. 48.

- "Alaskan Way By-Pass Asked". The Seattle Times. June 30, 1938. p. 36.

- Bureau of Public Roads (April 27, 1939). Toll Roads and Free Roads. Government Printing Office. p. 19. OCLC 2843728. Retrieved August 5, 2018 – via HathiTrust.

- Weingroff, Richard F. "Designating the Urban Interstates". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- Tate, Cassandra (November 8, 2004). "Washington Legislature authorizes construction of limited access highways in 1947". HistoryLink. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- "State Outlines Plans for New Super-Highway". The Daily Chronicle. Centralia, Washington. Associated Press. April 28, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved August 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cunningham, Ross (May 9, 1951). "Many Lawyers Back Langlie View That Highway Bond Issue Is Unconstitutional". The Seattle Times. p. 10.

- Cunningham, Ross (June 27, 1951). "Upholding Highway Bond Law Seen as Paving Way For Income-Tax O. K.". The Seattle Times. p. 20.

- Cunningham, Ross (February 3, 1952). "Knotty Financial, Traffic Problems Face Building Freeway Through Seattle". The Seattle Times. p. 12.

- Dugovich, William (May 1967). "Seattle's Superfreeway". Washington Highways. 14 (2). Washington State Department of Highways. pp. 2–5. OCLC 29654162. Retrieved September 11, 2018 – via WSDOT Library Digital Collections.

- Hittle, Leroy (May 21, 1953). "Paving Near Castle Rock Is Completed". The Seattle Times. p. 28.

- "Four-Lane Highway Near Kalama Due for Completion by January". The Daily Chronicle. Centralia, Washington. December 20, 1951. p. 9. Retrieved August 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "More Highway Will Be Paved". The Daily Chronicle. Centralia, Washington. February 15, 1952. p. 7. Retrieved August 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Patty, Stanton (October 31, 1954). "Highway Section Opens". The Seattle Times. p. 22.

- "New Highway Link Opened". The Daily Chronicle. Centralia, Washington. September 15, 1954. p. 1. Retrieved August 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Fort Lewis Bottlenecks To Be Broken". Washington Highways. 6 (9). Washington State Department of Highways. March 1957. pp. 8–9. OCLC 29654162. Retrieved September 12, 2018 – via WSDOT Library Digital Collections.

- "Traffic Flows on New Freeway". Fairbanks News-Miner. Associated Press. April 1, 1955. p. 10. Retrieved August 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Batcheldor, Matt (December 7, 2008). "I-5 at 50: It's changed the face of the region". The Olympian. p. A1.

- "New 4-Lane Link in '99' Is Opened". The Seattle Times. United Press International. December 22, 1955. p. 29.

- "Construction for Busy U.S. 99 Begun Early; Much More Due in Future". Washington Highway News. 8 (1). Washington State Department of Highways. August 1958. pp. 8–10. OCLC 29654162. Retrieved September 12, 2018 – via WSDOT Library Digital Collections.

- Cunningham, Ross (December 5, 1956). "State High Court's Decision Means No Expressway Tolls". The Seattle Times. p. 15.

- Hittle, Leroy (October 9, 1957). "State's Two Major Highways To Be Renumbered In Defense System". Port Angeles Evening News. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved August 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Becker, Paula (April 30, 2003). "First part of Seattle Freeway (Interstate 5) route receives federal funding on October 1, 1957". HistoryLink. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Jaques, Tom (October 4, 1959). "Engineers Closing Gaps in North-South Highway That Will Link Canada, Maxico; Washington Leads California, Oregon In Amount of Work Done". Eugene Register-Guard. p. C1. Retrieved September 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Two Key Projects on Highway 99 Progress Rapidly". The Seattle Times. July 26, 1957. p. 15.

- "New Fort Lewis Road Opened To Highway Traffic". Washington Highway News. 7 (4). Washington State Department of Highways. October 1957. p. 24. OCLC 29654162. Retrieved September 11, 2018 – via WSDOT Library Digital Collections.

- "Freeway Open in Olympia". The Daily Chronicle. Centralia, Washington. Associated Press. December 12, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved September 12, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Four Lane Roadway Pushing North". Washington Highway News. 8 (3). Washington State Department of Highways. December 1958. p. 14. OCLC 29654162. Retrieved September 12, 2018 – via WSDOT Library Digital Collections.

- "1st Stretch of Freeway To Be Opened Tomorrow". The Seattle Times. September 30, 1959. p. 20.

- "Tacoma Opens New Section Of Freeway". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. October 1, 1959. p. 15.

- "Sign of the times". The Seattle Times. March 9, 1958. p. 43.

- "Interstate Construction Program Forging Ahead". Washington Highway News. 8 (5). Washington State Department of Highways. April 1959. pp. 2–4. OCLC 29654162. Retrieved September 13, 2018 – via WSDOT Library Digital Collections.

- "Rosellini Will Push Freeway Projects". The Seattle Times. August 30, 1960. p. 21.

- Fish, Byron (September 4, 1964). "Everett Interurban Did a Freeway's Job". The Seattle Times. p. 24.

- "Seattle-Everett freeway opens today". The Enterprise. Lynnwood, Washington. February 3, 1965. p. 1.

- Mansfield, Tom (May 14, 1969). "I-5 Opened Today". The Everett Herald. p. A1.

- David A. Cameron; Lynne Grimes; Jane Wyatt (2005). David A. Cameron, Jane Wyatt (ed.). Snohomish County: An Illustrated History. cover design by James D. Kramer. Kelcema Books LLC. pp. 331–332. ISBN 0-9766700-0-3.