Igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ignis meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava. The magma can be derived from partial melts of existing rocks in either a planet's mantle or crust. Typically, the melting is caused by one or more of three processes: an increase in temperature, a decrease in pressure, or a change in composition. Solidification into rock occurs either below the surface as intrusive rocks or on the surface as extrusive rocks. Igneous rock may form with crystallization to form granular, crystalline rocks, or without crystallization to form natural glasses. Igneous rocks occur in a wide range of geological settings: shields, platforms, orogens, basins, large igneous provinces, extended crust and oceanic crust.

Geological significance

Igneous and metamorphic rocks make up 90–95% of the top 16 km of the Earth's crust by volume.[1] Igneous rocks form about 15% of the Earth's current land surface.[note 1] Most of the Earth's oceanic crust is made of igneous rock.

Igneous rocks are also geologically important because:

- their minerals and global chemistry give information about the composition of the mantle, from which some igneous rocks are extracted, and the temperature and pressure conditions that allowed this extraction, and/or of other pre-existing rock that melted;

- their absolute ages can be obtained from various forms of radiometric dating and thus can be compared to adjacent geological strata, allowing a time sequence of events;

- their features are usually characteristic of a specific tectonic environment, allowing tectonic reconstitutions (see plate tectonics);

- in some special circumstances they host important mineral deposits (ores): for example, tungsten, tin, and uranium are commonly associated with granites and diorites, whereas ores of chromium and platinum are commonly associated with gabbros.

Geological setting

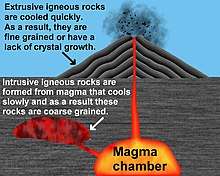

In terms of modes of occurrence, igneous rocks can be either intrusive (plutonic and hypabyssal) or extrusive (volcanic).

Intrusive

1. Laccolith

2. Small dike

3. Batholith

4. Dike

5. Sill

6. Volcanic neck, pipe

7. Lopolith

Note: As a general rule, in contrast to the smoldering volcanic vent in the figure, these names refer to the fully cooled and usually millions-of-years-old rock formations, which are the result of the underground magmatic activity shown.

Intrusive igneous rocks make up the majority of igneous rocks and are formed from magma that cools and solidifies within the crust of a planet (known as plutons), surrounded by pre-existing rock (called country rock); the magma cools slowly and, as a result, these rocks are coarse-grained. The mineral grains in such rocks can generally be identified with the naked eye. Intrusive rocks can also be classified according to the shape and size of the intrusive body and its relation to the other formations into which it intrudes. Typical intrusive formations are batholiths, stocks, laccoliths, sills and dikes. When the magma solidifies within the earth's crust, it cools slowly forming coarse textured rocks, such as granite, gabbro, or diorite.

The central cores of major mountain ranges consist of intrusive igneous rocks, usually granite. When exposed by erosion, these cores (called batholiths) may occupy huge areas of the Earth's surface.

Intrusive igneous rocks that form at depth within the crust are termed plutonic (or abyssal) rocks and are usually coarse-grained. Intrusive igneous rocks that form near the surface are termed subvolcanic or hypabyssal rocks and they are usually medium-grained. Hypabyssal rocks are less common than plutonic or volcanic rocks and often form dikes, sills, laccoliths, lopoliths, or phacoliths.

Extrusive

Extrusive igneous rocks, also known as volcanic rocks, are formed at the crust's surface as a result of the partial melting of rocks within the mantle and crust. Extrusive igneous rocks cool and solidify more quickly than intrusive igneous rocks. They are formed by the cooling of molten magma on the earth's surface. The magma, which is brought to the surface through fissures or volcanic eruptions, solidifies at a faster rate. Hence such rocks are smooth, crystalline and fine-grained. Basalt is a common extrusive igneous rock and forms lava flows, lava sheets and lava plateaus. Some kinds of basalt solidify to form long polygonal columns. The Giant's Causeway in Antrim, Northern Ireland is an example.

The molten rock, with or without suspended crystals and gas bubbles, is called magma. It rises because it is less dense than the rock from which it was created. When magma reaches the surface from beneath water or air, it is called lava. Eruptions of volcanoes into air are termed subaerial, whereas those occurring underneath the ocean are termed submarine. Black smokers and mid-ocean ridge basalt are examples of submarine volcanic activity.

The volume of extrusive rock erupted annually by volcanoes varies with plate tectonic setting. Extrusive rock is produced in the following proportions:[3]

- divergent boundary: 73%

- convergent boundary (subduction zone): 15%

- hotspot: 12%.

The behaviour of lava—magma that erupts from a volcano—depends upon its viscosity, which is determined by temperature, composition, crystal content and the amount of silica it contains. High-temperature magma, most of which is basaltic in composition, behaves in a manner similar to thick oil and, as it cools, treacle. Long, thin basalt flows with pahoehoe surfaces are common. Intermediate composition magma, such as andesite, tends to form cinder cones of intermingled ash, tuff and lava, and may have a viscosity similar to thick, cold molasses or even rubber when erupted. Felsic magma, such as rhyolite, is usually erupted at low temperature and is up to 10,000 times as viscous as basalt. Volcanoes with rhyolitic magma commonly erupt explosively, and rhyolitic lava flows are typically of limited extent and have steep margins because the magma is so viscous.

Felsic and intermediate magmas that erupt often do so violently, with explosions driven by the release of dissolved gases—typically water vapour, but also carbon dioxide. Explosively erupted pyroclastic material is called tephra and includes tuff, agglomerate and ignimbrite. Fine volcanic ash is also erupted and forms ash tuff deposits, which can often cover vast areas.

Because lava usually cools and crystallizes rapidly, it is usually fine-grained. If the cooling has been so rapid as to prevent the formation of even small crystals after extrusion, the resulting rock may be mostly glass (such as the rock obsidian). If the cooling of the lava happened more slowly, the rock would be coarse-grained.

Because the minerals are mostly fine-grained, it is much more difficult to distinguish between the different types of extrusive igneous rocks than between different types of intrusive igneous rocks. Generally, the mineral constituents of fine-grained extrusive igneous rocks can only be determined by examination of thin sections of the rock under a microscope, so only an approximate classification can usually be made in the field.

Classification

Igneous rocks are classified according to mode of occurrence, texture, mineralogy, chemical composition, and the geometry of the igneous body.

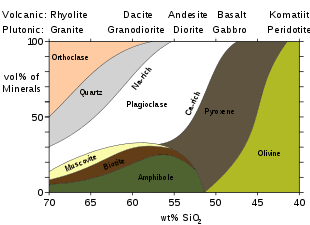

The classification of the many types of different igneous rocks can provide us with important information about the conditions under which they formed. Two important variables used for the classification of igneous rocks are particle size, which largely depends on the cooling history, and the mineral composition of the rock. Feldspars, quartz or feldspathoids, olivines, pyroxenes, amphiboles, and micas are all important minerals in the formation of almost all igneous rocks, and they are basic to the classification of these rocks. All other minerals present are regarded as nonessential in almost all igneous rocks and are called accessory minerals. Types of igneous rocks with other essential minerals are very rare, and these rare rocks include those with essential carbonates.

In a simplified classification, igneous rock types are separated on the basis of the type of feldspar present, the presence or absence of quartz, and in rocks with no feldspar or quartz, the type of iron or magnesium minerals present. Rocks containing quartz (silica in composition) are silica-oversaturated. Rocks with feldspathoids are silica-undersaturated, because feldspathoids cannot coexist in a stable association with quartz.

Igneous rocks that have crystals large enough to be seen by the naked eye are called phaneritic; those with crystals too small to be seen are called aphanitic. Generally speaking, phaneritic implies an intrusive origin; aphanitic an extrusive one.

An igneous rock with larger, clearly discernible crystals embedded in a finer-grained matrix is termed porphyry. Porphyritic texture develops when some of the crystals grow to considerable size before the main mass of the magma crystallizes as finer-grained, uniform material.

Igneous rocks are classified on the basis of texture and composition. Texture refers to the size, shape, and arrangement of the mineral grains or crystals of which the rock is composed.

Texture

Texture is an important criterion for the naming of volcanic rocks. The texture of volcanic rocks, including the size, shape, orientation, and distribution of mineral grains and the intergrain relationships, will determine whether the rock is termed a tuff, a pyroclastic lava or a simple lava.

However, the texture is only a subordinate part of classifying volcanic rocks, as most often there needs to be chemical information gleaned from rocks with extremely fine-grained groundmass or from airfall tuffs, which may be formed from volcanic ash.

Textural criteria are less critical in classifying intrusive rocks where the majority of minerals will be visible to the naked eye or at least using a hand lens, magnifying glass or microscope. Plutonic rocks also tend to be less texturally varied and less prone to gaining structural fabrics. Textural terms can be used to differentiate different intrusive phases of large plutons, for instance porphyritic margins to large intrusive bodies, porphyry stocks and subvolcanic dikes (apophyses). Mineralogical classification is most often used to classify plutonic rocks. Chemical classifications are preferred to classify volcanic rocks, with phenocryst species used as a prefix, e.g. "olivine-bearing picrite" or "orthoclase-phyric rhyolite".

- see also List of rock textures and Igneous textures

Chemical classification and petrology

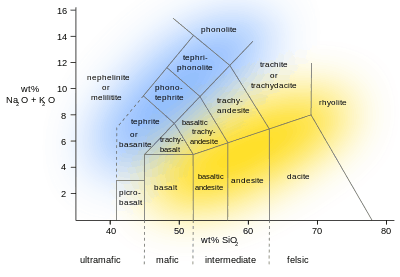

Igneous rocks can be classified according to chemical or mineralogical parameters.

Chemical: total alkali-silica content (TAS diagram) for volcanic rock classification used when modal or mineralogic data is unable to be determined due to the small grain size.

- felsic igneous rocks containing a high silica content, greater than 63% SiO2 (examples granite and rhyolite),

- intermediate igneous rocks containing between 52–63% SiO2 (example andesite and dacite),

- mafic igneous rocks have low silica 45–52% and typically high iron – magnesium content (example gabbro and basalt),

- ultramafic rock igneous rocks with less than 45% silica (examples picrite, komatiite and peridotite),

- alkalic igneous rocks with 5–15% alkali (K2O + Na2O) content or with a molar ratio of alkali to silica greater than 1:6 (examples phonolite and trachyte).

Chemical classification also extends to differentiating rocks that are chemically similar according to the TAS diagram, for instance:

- Ultrapotassic – rocks containing molar K2O/Na2O >3.

- Peralkaline – rocks containing molar (K2O + Na2O)/Al2O3 >1.

- Peraluminous – rocks containing molar (K2O + Na2O)/Al2O3 <1.

An idealized mineralogy (the normative mineralogy) can be calculated from the chemical composition, and the calculation is useful for rocks too fine-grained or too altered for identification of minerals that crystallized from the melt. For instance, normative quartz classifies a rock as silica-oversaturated; an example is rhyolite. In an older terminology, silica oversaturated rocks were called silicic or acidic where the SiO2 was greater than 66% and the family term quartzolite was applied to the most silicic. A normative feldspathoid classifies a rock as silica-undersaturated; an example is nephelinite.

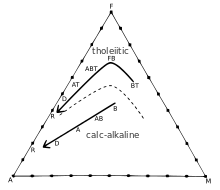

Magmas are further divided into three series:

- The tholeiitic series – basaltic andesites and andesites.

- The calc-alkaline series – andesites.

- The alkaline series – subgroups of alkaline basalts and the rare, very high potassium-bearing (i.e. shoshonitic) lavas.

These three magma series occur in a range of plate tectonic settings. Tholeiitic magma series rocks are found, for example, at mid-ocean ridges, back-arc basins, oceanic islands formed by hotspots, island arcs and continental large igneous provinces.[5]

All three series are found in relatively close proximity to each other at subduction zones where their distribution is related to depth and the age of the subduction zone. The tholeiitic magma series is well represented above young subduction zones formed by magma from relatively shallow depth. The calc-alkaline and alkaline series are seen in mature subduction zones, and are related to magma of greater depths. Andesite and basaltic andesite are the most abundant volcanic rock in island arc which is indicative of the calc-alkaline magmas. Some island arcs have distributed volcanic series as can be seen in the Japanese island arc system where the volcanic rocks change from tholeiite—calc-alkaline—alkaline with increasing distance from the trench.[6][7]

History of classification

In 1902, a group of American petrographers proposed that all existing classifications of igneous rocks should be discarded and replaced by a "quantitative" classification based on chemical analysis. They showed how vague, and often unscientific, much of the existing terminology was and argued that as the chemical composition of an igneous rock was its most fundamental characteristic, it should be elevated to prime position.[8]

Geological occurrence, structure, mineralogical constitution—the hitherto accepted criteria for the discrimination of rock species—were relegated to the background. The completed rock analysis is first to be interpreted in terms of the rock-forming minerals which might be expected to be formed when the magma crystallizes, e.g., quartz feldspars, olivine, akermannite, Feldspathoids, magnetite, corundum, and so on, and the rocks are divided into groups strictly according to the relative proportion of these minerals to one another.[9][8]

Mineralogical classification

For volcanic rocks, mineralogy is important in classifying and naming lavas. The most important criterion is the phenocryst species, followed by the groundmass mineralogy. Often, where the groundmass is aphanitic, chemical classification must be used to properly identify a volcanic rock.

Mineralogic contents – felsic versus mafic

- felsic rock, highest content of silicon, with predominance of quartz, alkali feldspar and/or feldspathoids: the felsic minerals; these rocks (e.g., granite, rhyolite) are usually light coloured, and have low density.

- mafic rock, lesser content of silicon relative to felsic rocks, with predominance of mafic minerals pyroxenes, olivines and calcic plagioclase; these rocks (example, basalt, gabbro) are usually dark coloured, and have a higher density than felsic rocks.

- ultramafic rock, lowest content of silicon, with more than 90% of mafic minerals (e.g., dunite).

For intrusive, plutonic and usually phaneritic igneous rocks (where all minerals are visible at least via microscope), the mineralogy is used to classify the rock. This usually occurs on ternary diagrams, where the relative proportions of three minerals are used to classify the rock.

The following table is a simple subdivision of igneous rocks according to both their composition and mode of occurrence.

| Composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of occurrence | Felsic | Intermediate | Mafic | Ultramafic |

| Intrusive | Granite | Diorite | Gabbro | Peridotite |

| Extrusive | Rhyolite | Andesite | Basalt | Komatiite |

For a more detailed classification see QAPF diagram.

Example of classification

Granite is an igneous intrusive rock (crystallized at depth), with felsic composition (rich in silica and predominately quartz plus potassium-rich feldspar plus sodium-rich plagioclase) and phaneritic, subeuhedral texture (minerals are visible to the unaided eye and commonly some of them retain original crystallographic shapes).

Magma origination

The Earth's crust averages about 35 kilometers thick under the continents, but averages only some 7–10 kilometers beneath the oceans. The continental crust is composed primarily of sedimentary rocks resting on a crystalline basement formed of a great variety of metamorphic and igneous rocks, including granulite and granite. Oceanic crust is composed primarily of basalt and gabbro. Both continental and oceanic crust rest on peridotite of the mantle.

Rocks may melt in response to a decrease in pressure, to a change in composition (such as an addition of water), to an increase in temperature, or to a combination of these processes.

Other mechanisms, such as melting from a meteorite impact, are less important today, but impacts during the accretion of the Earth led to extensive melting, and the outer several hundred kilometers of our early Earth was probably an ocean of magma. Impacts of large meteorites in the last few hundred million years have been proposed as one mechanism responsible for the extensive basalt magmatism of several large igneous provinces.

Decompression

Decompression melting occurs because of a decrease in pressure.[10]

The solidus temperatures of most rocks (the temperatures below which they are completely solid) increase with increasing pressure in the absence of water. Peridotite at depth in the Earth's mantle may be hotter than its solidus temperature at some shallower level. If such rock rises during the convection of solid mantle, it will cool slightly as it expands in an adiabatic process, but the cooling is only about 0.3 °C per kilometer. Experimental studies of appropriate peridotite samples document that the solidus temperatures increase by 3 °C to 4 °C per kilometer. If the rock rises far enough, it will begin to melt. Melt droplets can coalesce into larger volumes and be intruded upwards. This process of melting from the upward movement of solid mantle is critical in the evolution of the Earth.

Decompression melting creates the ocean crust at mid-ocean ridges. It also causes volcanism in intraplate regions, such as Europe, Africa and the Pacific sea floor. There, it is variously attributed either to the rise of mantle plumes (the "Plume hypothesis") or to intraplate extension (the "Plate hypothesis").[11]

Effects of water and carbon dioxide

The change of rock composition most responsible for the creation of magma is the addition of water. Water lowers the solidus temperature of rocks at a given pressure. For example, at a depth of about 100 kilometers, peridotite begins to melt near 800 °C in the presence of excess water, but near or above about 1,500 °C in the absence of water.[12] Water is driven out of the oceanic lithosphere in subduction zones, and it causes melting in the overlying mantle. Hydrous magmas composed of basalt and andesite are produced directly and indirectly as results of dehydration during the subduction process. Such magmas, and those derived from them, build up island arcs such as those in the Pacific Ring of Fire. These magmas form rocks of the calc-alkaline series, an important part of the continental crust.

The addition of carbon dioxide is relatively a much less important cause of magma formation than the addition of water, but genesis of some silica-undersaturated magmas has been attributed to the dominance of carbon dioxide over water in their mantle source regions. In the presence of carbon dioxide, experiments document that the peridotite solidus temperature decreases by about 200 °C in a narrow pressure interval at pressures corresponding to a depth of about 70 km. At greater depths, carbon dioxide can have more effect: at depths to about 200 km, the temperatures of initial melting of a carbonated peridotite composition were determined to be 450 °C to 600 °C lower than for the same composition with no carbon dioxide.[13] Magmas of rock types such as nephelinite, carbonatite, and kimberlite are among those that may be generated following an influx of carbon dioxide into mantle at depths greater than about 70 km.

Temperature increase

Increase in temperature is the most typical mechanism for formation of magma within continental crust. Such temperature increases can occur because of the upward intrusion of magma from the mantle. Temperatures can also exceed the solidus of a crustal rock in continental crust thickened by compression at a plate boundary. The plate boundary between the Indian and Asian continental masses provides a well-studied example, as the Tibetan Plateau just north of the boundary has crust about 80 kilometers thick, roughly twice the thickness of normal continental crust. Studies of electrical resistivity deduced from magnetotelluric data have detected a layer that appears to contain silicate melt and that stretches for at least 1,000 kilometers within the middle crust along the southern margin of the Tibetan Plateau.[14] Granite and rhyolite are types of igneous rock commonly interpreted as products of the melting of continental crust because of increases in temperature. Temperature increases also may contribute to the melting of lithosphere dragged down in a subduction zone.

Magma evolution

Most magmas only entirely melt for small parts of their histories. More typically, they are mixes of melt and crystals, and sometimes also of gas bubbles. Melt, crystals, and bubbles usually have different densities, and so they can separate as magmas evolve.

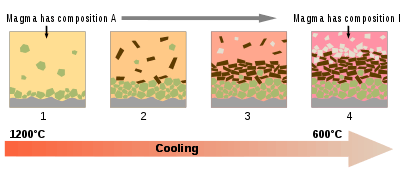

As magma cools, minerals typically crystallize from the melt at different temperatures (fractional crystallization). As minerals crystallize, the composition of the residual melt typically changes. If crystals separate from the melt, then the residual melt will differ in composition from the parent magma. For instance, a magma of gabbroic composition can produce a residual melt of granitic composition if early formed crystals are separated from the magma. Gabbro may have a liquidus temperature near 1,200 °C, and the derivative granite-composition melt may have a liquidus temperature as low as about 700 °C. Incompatible elements are concentrated in the last residues of magma during fractional crystallization and in the first melts produced during partial melting: either process can form the magma that crystallizes to pegmatite, a rock type commonly enriched in incompatible elements. Bowen's reaction series is important for understanding the idealised sequence of fractional crystallisation of a magma.

Magma composition can be determined by processes other than partial melting and fractional crystallization. For instance, magmas commonly interact with rocks they intrude, both by melting those rocks and by reacting with them. Magmas of different compositions can mix with one another. In rare cases, melts can separate into two immiscible melts of contrasting compositions.

There are relatively few minerals that are important in the formation of common igneous rocks, because the magma from which the minerals crystallize is rich in only certain elements: silicon, oxygen, aluminium, sodium, potassium, calcium, iron, and magnesium. These are the elements that combine to form the silicate minerals, which account for over ninety percent of all igneous rocks. The chemistry of igneous rocks is expressed differently for major and minor elements and for trace elements. Contents of major and minor elements are conventionally expressed as weight percent oxides (e.g., 51% SiO2, and 1.50% TiO2). Abundances of trace elements are conventionally expressed as parts per million by weight (e.g., 420 ppm Ni, and 5.1 ppm Sm). The term "trace element" is typically used for elements present in most rocks at abundances less than 100 ppm or so, but some trace elements may be present in some rocks at abundances exceeding 1,000 ppm. The diversity of rock compositions has been defined by a huge mass of analytical data—over 230,000 rock analyses can be accessed on the web through a site sponsored by the U. S. National Science Foundation (see the External Link to EarthChem).

Etymology

The word "igneous" is derived from the Latin ignis, meaning "of fire". Volcanic rocks are named after Vulcan, the Roman name for the god of fire. Intrusive rocks are also called "plutonic" rocks, named after Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld.

Gallery

.jpg) Kanaga volcano in the Aleutian Islands with a 1906 lava flow in the foreground

Kanaga volcano in the Aleutian Islands with a 1906 lava flow in the foreground A "skylight" hole, about 6 m (20 ft) across, in a solidified lava crust reveals molten lava below (flowing towards the top right) in an eruption of Kīlauea in Hawaii

A "skylight" hole, about 6 m (20 ft) across, in a solidified lava crust reveals molten lava below (flowing towards the top right) in an eruption of Kīlauea in Hawaii.jpg) Devils Tower, an eroded laccolith in the Black Hills of Wyoming

Devils Tower, an eroded laccolith in the Black Hills of Wyoming.jpg) A cascade of molten lava flowing into Aloi Crater during the 1969-1971 Mauna Ulu eruption of Kilauea volcano

A cascade of molten lava flowing into Aloi Crater during the 1969-1971 Mauna Ulu eruption of Kilauea volcano Columnar jointing in the Alcantara Gorge, Sicily

Columnar jointing in the Alcantara Gorge, Sicily A laccolith of granite (light-colored) that was intruded into older sedimentary rocks (dark-colored) at Cuernos del Paine, Torres del Paine National Park, Chile

A laccolith of granite (light-colored) that was intruded into older sedimentary rocks (dark-colored) at Cuernos del Paine, Torres del Paine National Park, Chile An igneous intrusion cut by a pegmatite dike, which in turn is cut by a dolerite dike

An igneous intrusion cut by a pegmatite dike, which in turn is cut by a dolerite dike

See also

- List of rock types – A list of rock types recognized by geologists

- Metamorphic rock – Rock which was subjected to heat and pressure causing profound physical or chemical change

- Migmatite – A mixture of metamorphic rock and igneous rock

- Petrology – The branch of geology that studies the origin, composition, distribution and structure of rocks

- Sedimentary rock – Rock formed by the deposition and subsequent cementation of material

Notes

- 15% is the arithmetic sum of the area for intrusive plutonic rock (7%) plus the area for extrusive volcanic rock (8%).[2]

References

- Prothero, Donald R.; Schwab, Fred (2004). Sedimentary geology : an introduction to sedimentary rocks and stratigraphy (2nd ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7167-3905-0.

- Wilkinson, Bruce H.; McElroy, Brandon J.; Kesler, Stephen E.; Peters, Shanan E.; Rothman, Edward D. (2008). "Global geologic maps are tectonic speedometers—Rates of rock cycling from area-age frequencies". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 121 (5–6): 760–779. doi:10.1130/B26457.1.

- Fisher, R. V. & Schmincke H.-U., (1984) Pyroclastic Rocks, Berlin, Springer-Verlag

- Ridley, W. I., 2012, Petrology of Igneous Rocks, Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Occurrence Model, USGS Scientific Report 2010-5070-C, Chapter 15.

- http://courses.washington.edu/ess439/ESS%20439%20Lecture%2014%20slides.pdf

- Gill, J.B. (1982). "Andesites: Orogenic andesites and related rocks". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 46 (12): 2688. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(82)90392-1. ISSN 0016-7037.

- Pearce, J; Peate, D (1995). "Tectonic Implications of the Composition of Volcanic ARC Magmas". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 23 (1): 251–285. Bibcode:1995AREPS..23..251P. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.23.1.251.

-

- Cross, W. et al. (1903) Quantitative Classification of Igneous Rocks, Chicago, University of Chicago Press

- Geoff C. Brown; C. J. Hawkesworth; R. C. L. Wilson (1992). Understanding the Earth (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-521-42740-1.

- Foulger, G.R. (2010). Plates vs. Plumes: A Geological Controversy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6148-0.

- T. L. Grove, N. Chatterjee, S. W. Parman, and E. Medard, (2006)The influence of H2O on mantle wedge melting. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 249, p. 74-89

- R. Dasgupta and M. M. Hirschmann (2007) Effect of variable carbonate concentration on the solidus of mantle peridotite. American Mineralogist, v. 92, p. 370-379

- M. J. Unsworth et al. (2005) Crustal rheology of the Himalaya and Southern Tibet inferred from magnetotelluric data. Nature, v. 438, p. 78-81

Further reading

- R. W. Le Maitre (editor) (2002) Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms, Recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences, Subcommission of the Systematics of Igneous Rocks., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-66215-X

External links

| The Wikibook Historical Geology has a page on the topic of: Igneous rocks and stratigraphy |

| The Wikibook Historical Geology has a page on the topic of: Igneous rocks |

- USGS Igneous Rocks

- Igneous rock classification flowchart

- Igneous Rocks Tour, an introduction to Igneous Rocks

- The IUGS systematics of igneous rocks

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Igneous rocks. |