Diorite

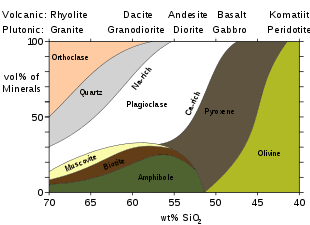

Diorite ( /ˈdaɪ.əˌraɪt/[1][2]) is an intrusive igneous rock composed principally of the silicate minerals plagioclase feldspar (typically andesine), biotite, hornblende, and/or pyroxene. The chemical composition of diorite is intermediate, between that of mafic gabbro and felsic granite. Diorite is usually grey to dark grey in colour, but it can also be black or bluish-grey, and frequently has a greenish cast. It is distinguished from gabbro on the basis of the composition of the plagioclase species; the plagioclase in diorite is richer in sodium and poorer in calcium. Diorite may contain small amounts of quartz, microcline, and olivine. Zircon, apatite, titanite, magnetite, ilmenite, and sulfides occur as accessory minerals.[3] Minor amounts of muscovite may also be present. Varieties deficient in hornblende and other dark minerals are called leucodiorite. When olivine and more iron-rich augite are present, the rock grades into ferrodiorite, which is transitional to gabbro. The presence of significant quartz makes the rock type quartz-diorite (>5% quartz) or tonalite (>20% quartz), and if orthoclase (potassium feldspar) is present at greater than 10 percent, the rock type grades into monzodiorite or granodiorite. A dioritic rock containing feldspathoid mineral/s and no quartz is termed foid-bearing diorite or foid diorite according to content.

Diorite has a phaneritic, often speckled, texture of coarse grain size and is occasionally porphyritic.

Orbicular diorite shows alternating concentric growth bands of plagioclase and amphibole surrounding a nucleus, within a diorite porphyry matrix.

Diorites may be associated with either granite or gabbro intrusions, into which they may subtly merge. Diorite results from the partial melting of a mafic rock above a subduction zone. It is commonly produced in volcanic arcs, and in cordilleran mountain building, such as in the Andes Mountains, as large batholiths. The extrusive volcanic equivalent rock type is andesite.

Occurrence

Diorite, although not rare, underlies comparatively small areas; source localities include Leicestershire (one name for microdiorite—markfieldite—exists due to the rock's being found in the village of Markfield) and Aberdeenshire, UK; Guernsey; Sondrio, Italy; Thuringia and Saxony in Germany; Finland; Romania; Northeastern Turkey; central Sweden; southern Vancouver Island around Victoria;[4] the Darrans range of New Zealand;[5] the Andes Mountains.[6]

An orbicular variety found in Corsica is called corsite.

Historic use

Diorite, being a mix of minerals, varies in its properties, but depending on the source it generally is moderately hard, variably reported as 5.5-7 on Mohs scale of mineral hardness. This makes it difficult to carve and work with, but also allows it to be worked finely and take a high polish, and to provide a durable finished work.

One comparatively frequent use of diorite was for inscription, as it is easier to carve in relief than in three-dimensional statuary. The use of diorite in art was most important among very early Middle Eastern civilizations such as Ancient Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, and Sumer. It was so valued in early times that the first great Mesopotamian empire—the Empire of Sargon of Akkad—listed the taking of diorite as a purpose of military expeditions.

Pallavas mamallapuram is a great example of diorite relief sculpture. Although one can find diorite art from later periods, it became more popular as a structural stone and was frequently used as pavement due to its durability. Diorite was used by both the Inca and Mayan civilizations, but mostly for fortress walls, weaponry, etc. It was especially popular with medieval Islamic builders. In later times, diorite was commonly used as cobblestone; today many diorite cobblestone streets can be found in England, Guernsey and Scotland, and scattered throughout the world in such places as Ecuador and China. Although diorite is rough-textured in nature, its ability to take a polish can be seen in the diorite steps of St. Paul's Cathedral, London, where centuries of foot traffic have polished the steps to a sheen.

Diorite statue of Gudea, Mesopotamia c. 2100 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Diorite statue of Gudea, Mesopotamia c. 2100 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art Diorite[7] Porphyry vase from predynastic Ancient Egypt, c. 3600 BC; approx. 30 cm.

Diorite[7] Porphyry vase from predynastic Ancient Egypt, c. 3600 BC; approx. 30 cm. Diorite statue of king Khafre 2500 BC in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Diorite statue of king Khafre 2500 BC in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo

See also

- List of rock types

References

- "Diorite". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Diorite". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- Blatt, Harvey and Robert J. Tracy (1996) Petrology, W. H. Freeman, 2nd edition, p. 53 ISBN 0-7167-2438-3

- Muller, J.E. (1980). Geology Victoria Map 1553A. Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada

- A Wandres; SD Weaver; D Shelley; JD Bradshaw (1998). "Diorites and associated intrusive and metamorphic rocks of the Darran Complex, Mount Underwood, Milford, southwest New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 41 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/00288306.1998.9514786.

- Harmon, R.S. and Rapela, C. W. (editors) (1991). Andean Magmatism and Its Tectonic Setting (Geological Society of America Special Paper 265). Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America. pp. 7, 35, 101, 180, 182, 186, 268. ISBN 0-8137-2265-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Catalog Number: 30677.nosub[1]". Field Museum Anthropological Collections catalog. Field Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diorite. |

| Look up diorite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |