Green Party of England and Wales

The Green Party of England and Wales (also known as the Green Party, Greens, or GPEW; Welsh: Plaid Werdd Cymru a Lloegr) is a green, left-wing political party in England and Wales. Headquartered in London, its co-leaders have been Siân Berry and Jonathan Bartley since September 2018. The Green Party has one representative in the House of Commons and, two in the House of Lords. It also has various councillors in the UK local government and two members of the London Assembly.

Green Party of England and Wales | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Jonathan Bartley and Siân Berry (job share) |

| Deputy leader | Amelia Womack |

| Chair | Liz Reason |

| Founded | 1990 |

| Preceded by | Green Party (UK) |

| Headquarters | The Biscuit Factory Unit 215 J Block 100 Clements Road London SE16 4DG |

| Youth wing | Young Greens of England and Wales |

| LGBT wing | LGBTIQA+ Greens |

| Membership (2019) | |

| Ideology | Green politics[2] Eco-socialism[3] Progressivism[4] Pro-Europeanism[5] British republicanism[6] |

| Political position | Left-wing[7][8] |

| European affiliation | European Green Party |

| International affiliation | Global Greens |

| Colours | Green |

| Devolved branches | Wales Green Party London Green Party |

| House of Commons[lower-alpha 1] | 1 / 573 |

| House of Lords[9] | 2 / 787 |

| London Assembly | 2 / 25 |

| National Assembly for Wales | 0 / 60 |

| Local government in England and Wales[10] | 382 / 18,560 |

| Website | |

| www | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Core topics

|

|

Four pillars

|

|

Perspectives

|

|

Organizations

|

|

Related topics

|

The party's ideology combines environmentalism with left-wing and centre-left economic policies, including well-funded, locally controlled public services within the confines of a steady-state economy with regulated capitalism, and supports proportional representation. It also takes a progressive approach to social policies such as civil liberties, animal rights, LGBT rights, and drug policy reform. The party also believes strongly in non-violence, basic income, a living wage, and democratic participation. They comprise various regional divisions, including the semi-autonomous Wales Green Party. Internationally, the party is affiliated to the Global Greens and the European Green Party.

The Green Party of England and Wales was established in 1990 alongside the Scottish Green Party and the Green Party in Northern Ireland through the division of the pre-existing Green Party, a group that had initially been established as the PEOPLE Party in 1973. Experiencing centralising reforms spearheaded by the Green 2000 group in early 1990, the party sought to emphasise growth in local governance, doing so throughout 1990. In 2010, the party gained its first Member of Parliament (MP) in former leader Caroline Lucas, who represents the constituency of Brighton Pavilion.

History

Origins (1972–1990)

The Green Party of England and Wales has its origins in the PEOPLE Party, which was founded in Coventry, Warwickshire, in February 1972.[11] It was renamed to The Ecology Party in 1975[12] and, in 1985, changed again to the Green Party.[13] In 1989, the party's Scottish branch split to establish the independent Scottish Green Party, with an independent Green Party in Northern Ireland developing shortly after, leaving the branches in England and Wales to form their own party.[14] The Green Party of England and Wales is registered with the Electoral Commission, only as "the Green Party."[15]

In the 1989 European Parliament elections, the Green Party polled 15% of the vote with 2.3 million votes, the best performance of a "green" party in a nationwide election.[16] This election gave the Green Party the third-largest share of the vote after the Conservative and Labour parties, although because of the first-past-the-post voting system, it failed to gain a seat.[17] Many say the success of the party is due to increased respect for environmentalism and the effects of the development boom in southern England in the late 1980s.[18]

Early years (1990–2008)

Seeking to capitalize on the Greens' success in the EP elections, a group named Green 2000 was established in July 1990, arguing for an internal reorganization of the party in order to develop it into an active electoral force capable of securing seats in the House of Commons.[19] Its proposed reforms included a more centralized structure, the replacement of the existing party council with a smaller party executive, and the establishment of delegate voting at party conferences.[20] Many party members opposed the reforms, believing that they would undermine the party's internal democracy and, amid the arguments, various vital members were dismissed or resigned from the Greens.[21] Although Green 2000 proposals were defeated at the party's 1990 conference, they were overwhelmingly carried at their 1991 conference, resulting in an internal restructuring of the party.[22] Between the end of 1990 and mid-1992, the party lost over half its members, with those polled indicating that frustration over a lack of clear and effective party leadership was a significant reason in their decision.[23] The party fielded more candidates than it had ever done before in the 1992 general election but performed poorly.[24]

In 1993, the party adopted its "Basis for Renewal" program in an attempt to bring together conflicting factions and thus saved the party from bankruptcy and potential demise.[25] The party sought to escape its reputation as an environmentalist single-issue party by placing greater emphasis on social policies.[26]

Recognizing their poor performance in the 1992 national elections, the party decided to focus on gaining support in local elections, targeting wards where there was a pre-existing support base of Green activists.[25] In 1993, future party leader and MP Caroline Lucas gained a seat in Oxfordshire County Council,[27] with other gains following in the 1995 and 1996 local elections.[25]

The Greens sought to build alliances with other parties in the hope of gaining representation at the parliamentary level.[28] In Wales, the Greens endorsed Plaid Cymru candidate Cynog Dafis in the 1992 general election, having worked with him on several environmental initiatives.[28] For the 1997 general election, the Ceredigion branch of the Greens endorsed Cynog Dafis as a joint Plaid Cymru/Green candidate, but this generated controversy with the party, with critics believing it improper to build an alliance with a party that did not share all of the Greens' views. In April 1995, the Green National Executive ruled that the party should withdraw from this alliance due to ideological differences.[28]

As the Labour Party shifted to the political center under the leadership of Tony Blair and his New Labour project, the Greens sought to gain the support of the party's disaffected leftists.[29]

During the 1999 European Parliament elections, the first to be held in the UK using proportional representation, the Greens gained their first Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), Lucas (South East England) and Jean Lambert (London).[30] At the inaugural London Assembly Elections in 2000, the party gained 11% of the vote and returned three Assembly Members (AMs).[31] Although this dropped to two following the 2004 London Assembly elections, the Green AMs proved vital in passing the annual budget of former Mayor Ken Livingstone.[29]

At the 2001 general election, they polled 0.7% of the vote and gained no seats.[32] At the 2004 European Parliamentary elections, the party returned 2 MEPs the same as in 1999; overall, the party polled 1,033,093 votes.[33] In the 2005 general election, the party gained over 1% of the vote for the first time and polled over 10% in the constituencies of Brighton Pavilion and Lewisham Deptford.[34] This growth was due in part to the increasing public visibility of the party as well as growth in support for smaller parties in the UK.[34]

Caroline Lucas (2008–2012)

In November 2007, the party held an internal referendum to decide on whether it should replace its use of two "principal speakers", one male and the other female, with the more conventional roles of "leader" and "deputy leader"; the motion passed with 73% of the vote.[35] In September 2008, the party then elected its first leader, Caroline Lucas,[35] with Adrian Ramsay elected deputy leader.[36] In the party's first election with Lucas as leader, it retained both its MEPs in the 2009 European elections.[37]

In the 2010 general election, the party returned its first MP. Lucas was returned as MP for the seat of Brighton Pavilion.[38] Following the election, Keith Taylor succeeded her as MEP for South East England. They also saved their deposit in Hove, and Brighton Kemptown.[39]

In the 2011 local government elections in England and Wales, the Green Party in Brighton and Hove took minority control of the City Council by winning 23 seats, 5 short of an overall majority.

At the 2012 local government elections, the Green Party gained 5 seats and retained both AMs at the 2012 London Assembly election. At the 2012 London mayoral election the party's candidate Jenny Jones finished third and lost her deposit.

Natalie Bennett (2012–2016)

In May 2012, Lucas announced that she would not seek re-election to the post of party leader.[40] In September, Natalie Bennett was elected party leader and Will Duckworth deputy leader in the leadership election took place.[41][42][43]

The 2013 local government elections saw overall gains of 5 seats. The party returned representation for the first time on the councils of Cornwall, Devon, and Essex.

At the local government elections the following year, the Greens gained 18 seats overall.[44] In London, the party won four seats, a gain of two, holding seats in Camden[45] and Lewisham,[46] and gaining seats in Islington[47] and Lambeth.[48]

At the 2014 European elections, the Green Party finished fourth, above the Liberal Democrats, winning over 1.2 million votes.[49] The party also increased its European Parliament representation, gaining one seat in the South West England region.[50]

In September 2014, the Green Party held its 2014 leadership elections. Incumbent leader Bennett ran uncontested and retained her status as a party leader. The election also saw a change in the elective format for the position of deputy leader. The party opted to elect two, gender-balanced deputy leaders, instead of one. Amelia Womack and Shahrar Ali won the two positions, succeeding former deputy leader Duckworth.[51]

In the 2010 general election, the Green Party contested roughly 50% of seats. The party announced in October 2014 that Green candidates would be standing for parliament in at least 75% of constituencies in the 2015 general election.[52] Following its rapid increase in membership and support, the Green Party also announced it was targeting twelve key seats for the 2015 general election: its one current seat, Brighton Pavilion, held by Lucas since 2010, Norwich South, a Liberal Democrat seat where June 2014 polling put the Greens in second place behind Labour,[53] Bristol West, another Liberal Democrat seat, where they targeted the student vote, St. Ives, where they received an average of 18% of the vote in county elections, Sheffield Central, Liverpool Riverside, Oxford East, Solihull, Reading East, and three more seats with high student populations – York Central, Cambridge, and Holborn and St. Pancras, where leader Bennett stood as the candidate.[54]

In December 2014, the Green Party announced that it had more than doubled its overall membership from 1 January that year to 30,809.[55] This reflected the increase seen in opinion polls in 2014, with Green Party voting intentions trebling from 2–3% at the start of the year, to 7–8% at the end of the year, on many occasions, coming in fourth place with YouGov's national polls, ahead of the Liberal Democrats, and gaining over 25% of the vote with 18 to 24-year-olds.[56][57] This rapid increase in support for the party is referred to by media as the "Green Surge".[58][59][60] The hashtag "#GreenSurge" has also been popular on social media (such as Twitter) from Green Party members and supporters[61] and, as of 15 January 2015, the combined Green Party membership in the UK stood at 44,713; greater than the number of members of UKIP (at 41,943), and the Liberal Democrats (at 44,576).[62]

Views subsequently fell back as the 2015 general election opinion polls arrived:[63] a Press Association poll of polls on 3 April, for example, put the Greens fifth with 5.4%.[64] However, membership statistics continued to surge with the party attaining 60,000 in England and Wales that April.

In the 2015 general election, Lucas was re-elected in Brighton Pavilion with an increased majority and, while failing to gain any additional seats, the Greens received their highest-ever vote share (over 1.1 million votes), and increased their national share of the vote from 1% to 3.8%.[65] Overnight, the membership numbers increased to over 63,000.[66] However, they lost 9 out of their 20 seats on the Brighton and Hove council, losing minority control.[67] Nationwide, the Greens increased their share of councillors, gaining an additional 10 council seats while failing to gain overall control of any individual council.[68]

Lucas and Bartley (2016–2018)

On 15 May 2016, Bennett announced she would not be standing for re-election in the party's biennial leadership election due to take place in the summer.[69] Former leader Lucas and Jonathan Bartley announced two weeks later that they intended to stand for leadership as a job share arrangement. Nominations closed at the end of June, with the campaign period taking place in July and voting period in August and the results announced at the party's Autumn Conference in Birmingham from 2–4 September. It was announced on 4 September that Lucas and Bartley would become the party's leaders in a job share.[71]

Lucas first suggested "progressive pacts" to work on a number of issues including combating climate change and for electoral reform, following the results of the 2015 general election.[72] She then reiterated the call alongside Bartley as they announced their plan to share the leadership of the party. Following the vote to leave the European Union in June 2016, Bennett published an open letter, calling for an "anti-Brexit alliance" potentially comprising Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Plaid Cymru to stand in a future snap election in English and Welsh seats.[73] The Green Party stood in 457 seats in the 2017 general election, securing 1.6% of the overall vote, and an average of 2.2% in seats it stood in.[74] While it was a disappointing result after the 2015 success, this was still the second-best Green result in a general election, and Brighton Pavilion remained Green with an increased majority.

On 30 May 2018, Lucas announced she would not seek re-election in the 2018 Green Party of England and Wales leadership election and would stand down as co-leader.[75] On 1 June 2018 Bartley announced a co-leadership bid alongside Siân Berry, former candidate for the Mayor of London in 2008 and 2016.[76]

Bartley and Berry (2018–)

Bartley and Berry were elected as co-leaders in September 2018, winning 6,279 of 8,329 votes.[77] In the 2019 local elections, the Green Party secured their best ever local election result, more than doubling their number of council seats from 178 to 372 councillors.[78] This success was followed by a similarly successful European election where Greens won (including Scottish Greens and the Green Party in Northern Ireland) over two million votes for the first time since 1989, securing 7 MEPs, up from 3. This included winning seats for the first time in the East of England, North West England, West Midlands and Yorkshire & the Humber.[79]

The membership also saw another climb in 2019, returning to 50,000 members in September.[1]

Ideology and policy

Sociologist Chris Rootes stated that the Green Party took "the left-libertarian" vote,[80] while Dennison and Goodwin characterised it as reflecting "libertarian-universalistic values".[81] The party wants an end to big government – which they see as hindering open and transparent democracy – and want to limit the power of big business – which, they argue, upholds the unsustainable trend of globalisation, and is detrimental to local trade and economies.[82] There have been allegations of factionalism and infighting in the Green Party between liberal, socialist, and anarchist factions.[83]

The party publishes a full set of its policies, as approved by successive party conferences, collectively entitled Policies for a Sustainable Society (originally The Manifesto for a Sustainable Society before February 2010).[84] This manifesto was summarised by LGBT and human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell as "radical socialist", "incorporat[ing] key socialist values" as it "rejects privatisation, free-market economics and globalisation, and includes commitments to public ownership, workers' rights, economic democracy, progressive taxation and the redistribution of wealth and power".[85]

Manifesto

The party publishes a manifesto for each of its election campaigns.[84] In their 2015 Election Manifesto, for the 2015 general election, the Greens outlined many new policies, including a Robin Hood tax on banks, and a new 60% tax on those earning over £150,000.[86]

In their 2019 Manifesto, the party outlined their key policies including remaining in and transforming the EU, investing in public services, simplifying income tax and increasing the rate of corporation tax to 24%.[87] The 2019 Manifesto has four key pillars: remain and transform, grow democracy, the green quality of life guarantee, the new deal for tax and spend. Remain and transform advocates for Britain to remain within the European Union and an increase in cross-border cooperation. Grow democracy aims to revolutionise the current voting system and rebalance government power, specifically through lowering the voting age to 16 and redefining the jurisdiction of local governments. The green quality of life guarantee addresses social issues such as housing, the National Health Service, education, countryside conservation, discrimination, crime, drug reform and animal rights. A major proposal within this section is a Universal Basic Income. The new deal for tax and spend outlines the party's economic policies including simplifying income tax, making big business pay its fair share, supporting small business and ending wasteful spending.[88]

Economic policy

The Green Party believes in "an economy that works for all". This includes radical steps to eliminate poverty with ambitious social policies such as increasing the minimum wage in line with the living wage. They also want to introduce a four-day working week; many economists say this will result in stagnant economic growth, while others say it would boost productivity and growth as Mondays and Fridays are the least productive days in the week.[89]

In November 2019, the Greens pledged to introduce a basic income by 2025, which will give every adult in the United Kingdom (unemployed or not) at least £89 a week (with additional payments to those facing barriers to work, including disabled people and single parents).[90] This is in order to tackle poverty, give people financial security, give people more freedom of choice to cut their working hours, start a green new business, take part in the community, or improve their own well being.[90] The policy also aims to tackle the rising levels of automation that threaten to put millions out of work and fundamentally change British industry.[91]

The Green Party wants to raise corporation tax from the current 19% to a higher amount, this is designed to generate more government revenue and insure large corporations do not become too powerful. The party wants to end subsidies for fossil fuels and replace them with subsidies for renewable energy sources such as wind, solar power and tidal power. Investment in green energy could potentially create more jobs and boost the economy or result is stagnant growth. The environmental economic policy also includes a Green deal that the Green Party say will generate new jobs and reduce Britain's energy costs. The Green Party wants to increase Britain's development and its position on the Human Development Index and free time index. They believe that uncontrolled economic growth has contributed to pollution and global warming and that more steps should be taken to ensure that growth is sustainable and keeps environmental damage to a minimum.[92]

Environmental policy

The party states that it would phase out fossil fuel-based power generation, and would work toward closing coal-fired power stations as soon as possible. The Green Party would also remove subsidies for nuclear power within ten years and work towards phasing out nuclear energy. The party aims for the UK to become carbon neutral. The Green Party Manifesto states:

The UK should base its future emissions budgets on the principles of science and equity and the aim of keeping global warming below 1.5 C. These principles entail the UK reducing its own emissions to net-zero by 2030 and seeking to reduce the emissions embedded in its imports to zero as soon as possible. The urgency of these objectives requires the UK to make overcoming the technological, political and social obstacles a national priority.[93]

The Green Party wants to set up an environmental protection committee to ensure the protection of habitats and to enhance biodiversity.

Foreign policy and defence

Since at least 1992, the party has emphasised unilateral nuclear disarmament and called for the rejection of the Trident nuclear programme of nuclear weapons in the United Kingdom.[94] To campaign for the latter, it has teamed up with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Plaid Cymru, and the Scottish National Party.[95] Former Leader Natalie Bennett has advocated replacing the UK Army with a "home defence force", according to The Telegraph.[96] "In the long term, it would take the UK out of NATO."[97]

The party has opposed the invasion of Iraq, NATO-led military intervention in Libya[98] and British involvement in Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen.[99]

The party campaigns for the rights of indigenous people around the world and argues for greater autonomy for these individuals. Furthermore, they support the granting of compensation and justice for historical wrongs, and that the reappropriation of lands and resources should be granted to certain nations and peoples. The party also believes that the canceling of international debt should take place immediately and any financial assistance should be in the form of grants and not loans, limiting debt service payments to 10% of export earnings per year.[82]

The Green Party advocate for a less "bully boy culture" from the Western world and more self-sustainability in terms of food and energy policy on a global level, with aid, only being given to countries as a last resort in order to prevent them from being indebted to their donors.[82]

Amid the toughening rhetoric surrounding immigration at the 2015 general election, the Greens issued mugs emblazoned with the slogan "Standing Up For Immigrants".[100] They claimed to offer a "genuine alternative" to the views of the mainstream parties by promoting the removal of restrictions on the number of foreign students, abolishing rules on family migration, and promoting further rights for asylum seekers.[81]

Drug policy

The Green Party has an official drugs group, for drugs policy and research.[101] The party wants to end the prohibition of drugs and create a system of legal regulation in order to minimise the harms associated with drug use as well as the harms associated with its production and supply.[102][103] The party's view is that people have always used drugs and there will always be people that will use them, and therefore focus should be on minimising the harms associated with drug use and tackling the causes of why people take drugs (e.g. poverty, isolation, mental illness, physical illness, and psychological trauma).[102] This sits alongside the party's belief that adults should be free to make informed decisions about their own drug consumption, while this freedom is also balanced with the government's responsibility to protect individuals and society from harm.[102] The party considers the drugs issue to be a health issue, rather than a criminal one.[104]

The party also supports opening overdose prevention centres in towns and cities in order to prevent fatal overdoses, the transmission of HIV, hepatitis C and other illnesses, as well as offering a place for drug users to access health and treatment services.[102] The party supports devolving the decision-making on whether to open these sites to police, health services and local authorities.[102]

Ian Barnett from the Green Party says that: "The Policy of 'War on Drugs' has clearly failed. We need a different approach to the control and misuse of drugs." However, the party does aim to minimise drug use due to the negative effects on the individual and society at large.[105]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

The stated aim of the sexual orientation and gender identity group within the party, known as LGBTIQA+ Greens, is to raise awareness on LGBTIQA+ rights and issues affecting the broader LGBTIQA+ community, as well as broader Green politics.[106]

The 2015 and 2017 general election manifestos contained policies on all teachers to be trained on LGBTIQA+ issues (such as "providing mandatory HIV, sex, and relationships education – age appropriate and LGBTIQA+-inclusive – in all schools from primary level onwards"), on reforming the system of pensions, on ending the "spousal veto" and on "mak[ing] equal marriage truly equal". Bennett has also voiced support for polygamy and polyamorous relationships.[107]

The Green Party supports same-sex marriage and, on Brighton and Hove City Council, considered expelling Christina Summers in 2012 due to opposition to same-sex marriage legislation on religious grounds.[108][109]

Transport

The Green party has called for "A People's Transport System"[110] to help deal with the issues not just to the planet but to local communities as well. The Green Party has an official transport working group, aimed at helping to draw up policies to be voted on at the conference.

The party also aims to prioritise accessibility to transport and create equal access irrespective of age, wealth or disability. The party also wants to reduce the total distance people travel and travel journey lengths by encouraging the development and retention of local facilities. It also seeks to reduce the environmental impacts of transport, partly through encouraging transport that makes use of sustainable and replaceable resources. The party would also implement a hierarchy of transport that would need to be followed by all levels of government:[111]

- Walking and disabled access.

- Cycling.

- Public transport (trains, light rail/trams, buses and ferries) and rail and water-borne freight.

- Light goods vehicles, taxis and low powered motorcycles.

- Private motorised transport (cars & high powered motorcycles).

- Heavy goods vehicles.

- Aeroplanes.

One of the flagship and long-standing policies in this field is returning the railways to public ownership[110] along with renationalising other forms of transport.

The party opposes High Speed 2 (HS2). The party regards the planned railway line as a waste of tax payers money and environmentally damaging. The party is, however, in favour of high speed rail in principle, providing projects meet strict criteria. The party wishes to instead use the billions invested in HS2 on other matters, such as upgrading and improving local public transport.[112][113][114][115][116][117]

Tuition fees

The party supports scrapping university and further education fees.[118][119] It supports all courses in further education being provided free at the point of use.[119] According to the Green Party:

"Under a green government all currently outstanding debts - yet to be paid - held by an individual, for undergraduate tuition fees and maintenance loans, and any resulting interest would be written off. Specifically, those issued by the Student Loans Company (SLC) and currently held by the UK government".[119]

Governance

Global governance

The party campaigns for greater accountability in global governance, with the United Nations made up of elected representatives and more regional representation, as opposed to the current nation-based setup. They want democratic control of the global economy with the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund and World Bank reformed, democratised or even replaced. The party also wishes to prioritise social and environmental sustainability as a global policy.[82]

National governance

The party advocates ending the first past the post voting system for UK parliamentary elections and replacing it with a form of proportional representation.[120]

The Green Party states that they believe there is "no place in government for the hereditary principle".[121]

The party supported Scottish independence in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum.[122]

European Union

The party supported the 2016 referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union, calling it "a vital opportunity to create a more democratic and accountable Europe, with a clearer purpose for the future".[123] The party has criticised the Common Agricultural Policy, the Common Fisheries Policy and the "excessive influence" of the European Commission in comparison to the European Council and European Parliament, describing it as "undemocratic and unaccountable".[124] The party favoured a "three yeses" approach to Europe: "yes to a referendum, yes to major EU reform and yes to staying in a reformed Europe". Bennett also added that:

'Yes to the EU' does not mean we are content with the union continuing to operate as it has in the past. There is a huge democratic deficit in its functioning, a serious bias towards the interests of neoliberalism and 'the market', and central institutions have been overbuilt. But to achieve those reforms we need to work with fellow EU members, not try to dictate high handedly to them, as David Cameron has done.[125]

Young Greens

The youth wing of the Green Party, the Young Greens (of England and Wales), has developed independently from around 2002 and is for all Green Party members aged up to 30 years old. There is no lower age limit. The Young Greens have their own constitution, national committee, campaigns and meetings, and have become an active presence at Green Party Conferences and election campaigns. There are now many Young Greens groups on UK university, college and higher-education institution campuses. Many Green Party councillors are Young Greens, as are some members of GPEx and other internal party organs.[126]

Membership and finances

According to accounts filed with the Electoral Commission, for the year ending 31 December 2010, the party had an income of £770,495 with expenditure of £889,867.[127] Membership increased rapidly in 2014, more than doubling in that year.[128] On 15 January 2015, the Green Party claimed that the combined membership of the UK Green Parties (Green Party of England and Wales, Scottish Green Party, and Green Party in Northern Ireland) had risen to 43,829 members, surpassing UKIP's membership of 41,966, and making it the third-largest UK-wide political party in the UK in terms of membership.[129][130] On 14 January 2015, UK newspaper The Guardian had reported that membership of the combined UK Green Parties was closing on those of UKIP and the Liberal Democrats, but noted that it lagged behind that of the Scottish National Party (SNP), which has a membership of 92,187 members but is not a UK-wide party.[131] Membership of the party peaked at over 67,000 members in the summer of 2015 after the general election, but has since declined subsequent to Jeremy Corbyn becoming leader of the Labour Party.[132]

| Year |

|

|---|---|

| 2002[133] | 5,268 |

| 2003[133] | 5,858 |

| 2004[134] | 6,281 |

| 2005[135] | 7,110 |

| 2006[136] | 7,019 |

| 2007[137] | 7,441 |

| 2008[138] | 7,553 |

| 2009[139] | 9,630 |

| 2010[127] | 12,768 |

| 2011[140] | 12,842 |

| 2012[141] | 12,619 |

| 2013[142] | 13,809 |

| 2014[143] | 30,900 |

| 2015[144] | 63,219 |

| 2016[145] | 45,643 |

| 2018[146] | 39,350 |

| 2019[1] | 50,000 |

Support base

— Sarah Birch, 2009[147]

According to political scientist Sarah Birch, the Green Party draws support from "a wide spectrum of the population".[148] In 1995, sociologist Chris Rootes stated that the Green Party "appeals disproportionately to younger, highly educated professional people", although he noted that this support base was "not predominantly urban".[149] In 2009, Birch noted that the Green's strongest areas of support were Labour-held seats in university towns or urban areas with relatively large student populations.[150] She noted that there were also strong correlations between areas of high Green support and high percentages of people who define themselves as having no religion.[151]

Birch noted that sociological polling revealed a "strong relationship" between individuals having voted for the Liberal Democrats in the past and holding favourable views of the Green Party, noting that the two groups were competing for "similar sorts of voters".[152]

Electoral representation

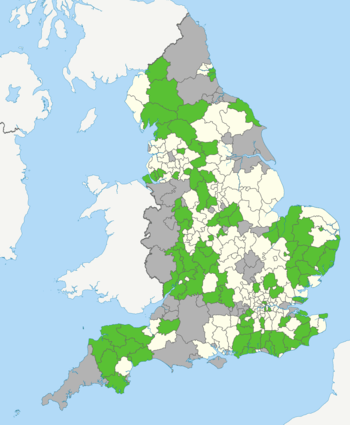

A map showing the representation of the Green Party of England and Wales at the Borough/City/District level of government, excluding Unitary Authorities (grey). |

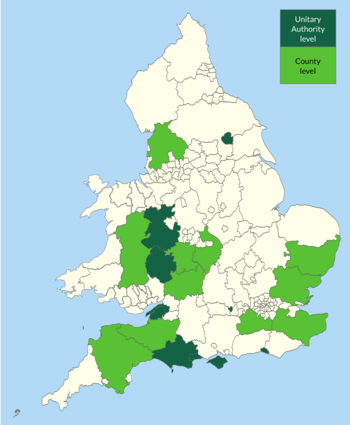

A map showing the representation of the Green Party of England and Wales at the County/Unitary Authority level of government. |

The party has one Member of Parliament, two Members of the House of Lords, seven Members of the European Parliament and two Members of the London Assembly.[153][154]

House of Commons

Brighton Pavilion was the Green Party's first and only parliamentary seat to date, won at the 2010 general election and held in 2015, 2017 and 2019. As with other small parties, representation at the House of Commons has been hindered by the first-past-the-post voting system.[155]

| Election | Principal Speakers | Votes | Seats | Government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ± | # | ± | ||||

| 1992 | Jean Lambert | Richard Lawson | 170,047 | 0.5 | 0 / 650 |

Conservative | ||

| 1997 | Peg Alexander | David Taylor | 61,731 | 0.3 | 0 / 659 |

Labour | ||

| 2001 | Margaret Wright | Mike Woodin | 166,477 | 0.6 | 0 / 659 |

Labour | ||

| 2005 | Caroline Lucas | Keith Taylor | 257,758 | 1.0 | 0 / 646 |

Labour | ||

| 2010 | Caroline Lucas | N/A | 265,247 | 0.9 | 1 / 650 |

Conservative–Liberal Democrats | ||

| 2015 | Natalie Bennett | 1,111,603 | 3.6 | 1 / 650 |

Conservative | |||

| 2017 | Caroline Lucas | Jonathan Bartley | 512,327 | 1.6 | 1 / 650 |

Conservative minority with DUP confidence & supply | ||

| 2019 | Jonathan Bartley | Siân Berry | 865,697 | 2.7 | 1 / 650 |

Conservative | ||

House of Lords

The party's first life peer was Lord (Tim) Beaumont, who defected from the Liberal Democrat group of peers in 1999, spoke frequently in the house and died in 2008.[156] Baroness (Jenny) Jones became the next peer, 2013–present.[157] Baroness (Natalie) Bennett joined her in 2019. She was appointed on the back of continued strong election results for the party, through Theresa May's resignation honours list.[158]

European Parliament

Since the first UK election to the European Parliament with proportional representation, in June 1999, the Green Party of England and Wales has had representation in the European Parliament. From 1999 to 2010, the two MEPs were Jean Lambert (London) and Lucas (South East England). In 2010, on election to the House of Commons, Lucas resigned her seat and was succeeded by Keith Taylor. In May 2014, Taylor and Lambert held their seats, and were joined by Molly Scott Cato who was elected in the South West region, increasing the number of Green Party Members of the European Parliament to three for the first time.[159] In May 2019, this number rose to seven: Scott Ainslie (London), Ellie Chowns (West Midlands), Gina Dowding (North West England), Magid Magid (Yorkshire and the Humber), Alexandra Phillips (South East England), Catherine Rowett (East of England), and the re-elected Scott Cato.[160]

| Election | Principal Speakers | Votes | Seats | Position | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ± | # | ± | ||||

| 1994 | John Cornford | Jan Clark | 471,257 | 3.0 | 0 / 87 |

|||

| 1999 | Mike Woodin | Jean Lambert | 568,236 | 5.3 | 2 / 87 |

|||

| 2004 | Mike Woodin | Caroline Lucas | 948,588 | 5.6 | 2 / 78 |

|||

| 2009 | Caroline Lucas | N/A | 1,223,303 | 7.8 | 2 / 72 |

|||

| 2014 | Natalie Bennett | N/A | 1,136,670 | 6.9 | 3 / 73 |

|||

| 2019 | Jonathan Bartley | Siân Berry | 1,881,306 | 11.8 | 7 / 73 |

|||

Local government

The party has representation at local government level in England. The party has limited representation on most councils on which it is represented.

From the early 1990s until 2009, the number of Green local councillors rose from zero to over 100[34] and was in minority control of Brighton and Hove City Council from 2011 to 2015.[162][163]

At the 2019 United Kingdom local elections a record number of Green Party candidates were elected, with many being the first Green candidates elected to their councils. The Party now has 372 councillors and is part of 9 council coalitions and supports a further coalition.

See also

- Anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom

- List of advocates of republicanism in the United Kingdom

- List of environmental organisations

- Politics of the United Kingdom

Notes

- English and Welsh seats only

References

- "BREAKING: Green Party membership hits 50,000". www.bright-green.org. Bright Green. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "United Kingdom". Parties and Elections in Europe. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Labour 'never challenged the austerity narrative' | Owen Jones talks to Caroline Lucas". YouTube. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- "Green Party of England and Wales elects new leaders". europeangreens.edu. European Green Party. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- "Green party 'loud and proud' about backing Britain in Europe". The Guardian. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "The Green Party Public Administration Policies". Green Party of England and Wales. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- The Independent – Election 2015: The Green Party want to give disgruntled left-wing voters a new voice Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Author – Morris, Nigel. The Independent [online]. Date retrieved 5 March 2015. Date published 3 September 2014.

- Bakker, Ryan; Jolly, Seth; Polk, Jonathan. "Mapping Europe's party systems: which parties are the most right-wing and left-wing in Europe?". London School of Economics / EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Members of the House of Lords: Other parties". www.parliament.uk. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Open Council Data UK – compositions councillors parties wards elections". www.opencouncildata.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- [The Independent – The Green Party: a short history]

- Rootes 1995, p. 66; Birch 2009, p. 54.

- McCulloch 1992, p. 421; Birch 2009, p. 54.

- Birch 2009, p. 54.

- "The Electoral Commission – Register of political parties – Green Party". The Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Pattie, Russell & Johnston 1991, p. 286; McCulloch 1992, p. 422; Rootes 1995, pp. 68–69; Burchell 2000, p. 145; Birch 2009, p. 54.

- Pattie, Russell & Johnston 1991, p. 286; Birch 2009, p. 54.

- Rootes 1995, pp. 69–72.

- McCulloch 1992, p. 422; Burchell 2000, p. 145.

- Burchell 2000, p. 145.

- Burchell 2000, pp. 145–146.

- McCulloch 1992, p. 422.

- Birch 2009, p. 68.

- Rootes 1995, p. 75.

- Burchell 2000, p. 146.

- Burchell 2000, p. 148.

- Rootes 1995, p. 79; Burchell 2000, p. 146.

- Burchell 2000, p. 147.

- Birch 2009, p. 55.

- Burchell 2000, pp. 145, 149.

- Burchell 2000, pp. 149–150; Birch 2009, p. 55.

- "Green vote doubles in two seats". BBC News. BBC Election 2005. 6 May 2005. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

In the 2001 general election the Green Party took 0.7% of the vote with no seats gained.

- "European Election: United Kingdom Result". Vote 2004. BBC. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Birch 2009, p. 56.

- Birch 2009, p. 67.

- "GPEx Candidates". Green Party. Tracy Dighton-Brown. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010.

- "2009 European Elections". Green Party. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- "Results: Brighton Pavilion". Election 2010. BBC. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "General Election 2010". Green Party of England and Wales. 2010. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- McCarthy, Michael (14 May 2012). "Green Party leader Lucas steps aside to aid fight against Lib Dems". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "New Leader and Deputy Leader announcement" (Press release). Green Party. 3 September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Jowit, Juliette (5 August 2004). "Green party elects Natalie Bennett as leader". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Natalie Bennett elected new Green Party leader in England and Wales". BBC News. 3 September 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Newweb > About the Council > News". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "Local Elections Results May 2014". Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- "Election results for 22 May 2014". GOV.uk. Lewisham Council. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Highbury East Ward". Archived from the original on 29 May 2014.

- "Who is representing you in Lambeth? – Love Lambeth". 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "Vote 2014 Election Results for the EU Parliament UK regions – BBC News". Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "South West". Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Derek Wall (September 2014). "Another Green World". Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Wintour, Patrick (2 December 2014). "Green party membership doubles to 27,600 as Ukip's reaches 40,000". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "Norwich South Polls (full tables)" (PDF). Norwich South: Lord Ashcroft Polls. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- Helm, Toby (19 October 2014). "Confident Greens eye 12 seats in England". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "ManchesterYoungGreen on Twitter". Twitter. Archived from the original on 29 November 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Opinion polling for the 2015 United Kingdom general election

- "YouGov / The Sun Survey Results" (PDF). YouGov.com. YouGov: What the world thinks. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Harris, John (25 October 2014). "The Green party surge – and why it's coming from Bristol and all points west". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Gander, Kashmira (2 December 2014). "Green Party membership doubles in England and Wales". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Election 2015: Odds for Green Party to claim Bristol West fall from 100/1 to 7/2". The Bristol Post. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "#GreenSurge on Twitter". Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Mason, Rowena (15 January 2015). "Green membership surge takes party past Lib Dems and Ukip". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- "Election 2015: Ahead of tonight's debate, Tories predicted to win most seats but lose power". May2015.com. New Statesman. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Election Live – 3 April – BBC News (10:29 – Poll of Polls)". BBC News. 3 April 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

Ukip are in third place on 13.3%, the Liberal Democrats are fourth on 7.8% and the Greens are fifth on 5.4%. However, it is too soon to judge whether the leaders' debate has had any impact upon levels of support, PA says.

- "UK vote share". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "Bennett leads 'second green surge'". The Westmorland Gazette. Press Association. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

We've had a good start in the last 24 hours – we've had about 1,000 more people join the Green Party so our membership has gone over 63,000, which means we are much bigger than Ukip and the Liberal Democrats.

- "Elections 2015: Green Party loses Brighton Council to Labour". BBC. 10 May 2015. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "England council results". BBC News. 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Stewart, Heather (15 May 2016). "Natalie Bennett to step down as Green party leader". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "Caroline Lucas and Jonathan Bartley elected Green leaders". 2 September 2016. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Perraudin, Frances (17 June 2015). "Caroline Lucas urges Labour to back 'progressive pacts' with other parties". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Walker, Peter (29 June 2016). "Greens urge anti-Brexit alliance in next general election". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- [Dennison, J., (2018), 'The rug pulled from under them: UKIP and the Greens in 2017' in Parliamentary Affairs 71 (1), p.104.]

- Caroline Lucas to step down as Green party co-leader Archived 21 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Author – Peter Walker. Published 30 May 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Jonathan Bartley and Sian Berry to run as Green co-leaders Archived 26 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. BBC NEWS. Published 1 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Jonathan Bartley and Sian Berry elected Green Party co-leaders". BBC News. 4 September 2018. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- "Local Election Results 2019". Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Graham-Harrison, Emma (2 June 2019). "A quiet revolution sweeps Europe as Greens become a political force". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Rootes 1995, p. 76.

- Dennison & Goodwin 2015, p. 185.

- Hanif, Faisal (15 January 2015). "What are the Green party's policies?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Harris, John (15 December 2013). "Have the Greens blown it in Brighton?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Policies for a Sustainable Society". Green Party. 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Tatchell, Peter. "Why I joined the Greens". Red Pepper Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Green Party: Mini Manifesto 2015". The Green Party of England and Wales. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Our Manifesto -". Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Our Manifesto". Green Party. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "The Best and Worst Days for Productivity". Smartsheet. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "General election 2019: Greens offer basic income by 2025". BBC News. 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Bartley, Jonathan (2 June 2017). "The Greens endorse a universal basic income. Others need to follow". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Pollution". policy.greenparty.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "The Climate Emergency". policy.greenparty.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Rootes 1995, p. 77.

- Burns, Malcolm (19 January 2015). "SNP, Plaid Cymru And Green Party Team Up on Trident Nuclear Weapons". Morning Star. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Hope, Christopher (25 January 2015). "British army to be replaced by 'home defence force' if Greens win power in May". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Peace & Defence". greenparty.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

In the long term, we would take the UK out of NATO.

- "Green Party Deputy Leader to speak at international anti-war conference. Archived 23 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine". GreenParty.org.uk. 5 June 2015.

- "Green Party condemns UK government support for massacres in Yemen Archived 23 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine". GreenParty.org.uk. 3 September 2015.

- Dennison & Goodwin 2015, pp. 184–185.

- "GPDG: news, research, and ecstasy testing kits". Green Party Drugs Group. Archived from the original on 14 March 2004. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Drug Policy". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Who should I vote for? General election 2019 policy guide". BBC News. 13 November 2019. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Green Party leader Natalie Bennett: Drugs misuse a 'health issue' not a 'criminal one'". ITV.com. ITV News. 1 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- Barnett, Ian (31 March 2015). "Decriminalisation of cannabis not the same as legalisation". Burnley Express. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "LGBTIQA+ Greens Website". LGBTIQA+ Greens. 24 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Duffy, Nick (1 May 2015). "Green Party wants every teacher to be trained to teach LGBTIQA+ issues". Pink News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- Bingham, John (27 July 2012). "Green council accused of 'vilifying' Christian over gay marriage stance". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "Gay marriage row expulsion upheld". BBC News. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "A Green Party manifesto for sustainable transport 2017". www.greenparty.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Transport". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). June 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Greens oppose HS2: "it wouldn't do what it says on the tin"". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Greens: Time to put HS2 out of its misery". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). 11 February 2019. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Greens: Carillion collapse final nail in HS2 coffin". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). 15 January 2018. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "HS2: Cases For And Against High-Speed Rail". Sky news. 10 January 2012. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Cameron says HS2 WILL go ahead". ITV News. 26 January 2013. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Hodgson, Camilla (4 October 2019). "Green party wants HS2 cash switched to local transport". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Quality Education, No Tuition Fees". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Education". Green Party of England and Wales (official website). January 2016. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Birch 2009, p. 65.

- "How does British politics operate?". Green Party of England and Wales. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "#GreenYesSupport: Greens Across Europe Show Support for Yes Vote | the Green Party". Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Freeman, Melissa. "Yes to an EU Referendum: Green MP calls for chance to build a better Europe". GreenParty.org.uk. The Green Party of England and Wales. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "Europe". Green Party of England and Wales. September 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Bennett, Natalie (23 January 2013). "Natalie Bennett unveils our "Three Yeses" to Europe". GreenParty.org.uk. The Green Party of England and Wales. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "Young Greens Website". Younggreens.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2010" (PDF). The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 4. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Green Party – Green Party Membership up 100% since January 1, 2014". Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "Green Party says it has more members than UKIP". www.bbc.co.uk. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Sabin, Lamiat (15 January 2015). "Greens get new member every 10 seconds to surge past Ukip's membership numbers ahead of general election". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Mason, Rowena (14 January 2015). "Greens close to overtaking Ukip and Lib Dems in number of members". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "More people join Labour since Corbyn win than are in Ukip". The Independent. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "The Green Party – Financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2003" (PDF). The Green Party. p. 5. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2004" (PDF). The Green Party. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2005" (PDF). The Green Party. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2006" (PDF). The Green Party. p. 3. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2007" (PDF). The Green Party. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2008" (PDF). The Green Party. p. 4. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2009" (PDF). The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2011". The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 4. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2012". The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 4. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2013". The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 4. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2014". The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 4. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- "The Green Party of England and Wales – Report and Financial Statements – Year ended 31 December 2015". The Green Party of England and Wales. p. 5. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- "Electoral Commission 2016". 31 December 2016. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Membership of UK political parties". www.parliament.uk. 3 September 2018. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Birch 2009, p. 61.

- Birch 2009, p. 53.

- Rootes 1995, p. 85.

- Birch 2009, pp. 58–59.

- Birch 2009, pp. 59–60.

- Birch 2009, p. 64.

- "BBC Democracy Live – Introductions". BBC Democracy Live. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Introduction: Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb: 5 Nov 2013: House of Lords debates – TheyWorkForYou". Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Rootes 1995, p. 68; Birch 2009, pp. 56, 65.

- Birch 2009, p. 66.

- "Millionaire donors and business leaders back Vote Leave campaign to exit EU". The Guardian. 9 October 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019 – via Press Association.

- "Natalie Bennett becomes second Green in the Lords". Business Green. 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Green Party of England and Wales election results#European Parliament elections

- "Green Party pushes Tories into fifth place in UK European election race as it more than doubles tally of MEPs". Evening Standard. 27 May 2019. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Compared to the Green Party (UK) position in 1989.

- "Guide to the 2010 European and local elections". BBC News. BBC. 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Stanley, Tim (18 October 2014). "Brighton has become an object lesson in why it is a disaster to vote Green". Spectator.comNews. The Spectator. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

Sources

- Birch, Sarah (2009). "Real Progress: Prospects for Green Party Support in Britain". Parliamentary Affairs. 62 (1): 53–71. doi:10.1093/pa/gsn037.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burchell, Jon (2000). "Here Come the Greens (Again): The Green Party in Britain during the 1990s". Environmental Politics. 9 (3): 145–150. doi:10.1080/09644010008414543.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carter, N.; Rootes, C. (2006). "The Environment and the Greens in the 2005 Elections in Britain". Environmental Politics. 15 (3): 473–478. doi:10.1080/09644010600627956.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doherty, B. (1992). "The Autumn 1991 Conference of the UK Green Party". Environmental Politics. 1 (2): 292–297. doi:10.1080/09644019208414026.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, G. (1993). "Hard Times for the British Green Party". Environmental Politics. 2 (2): 327–333. doi:10.1080/09644019308414077.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dennison, James; Goodwin, Matthew (2015). "Immigration, Issue Ownership and the Rise of UKIP". Parliamentary Affairs. 68: 168–187. doi:10.1093/pa/gsv034.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, R. (2006). "Can Environmentalism and Nationalism be Reconciled? The Plaid Cymru/Green Party Alliance, 1991–1995". Regional & Federal Studies. 16 (3): 315–332. doi:10.1080/13597560600852524.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCulloch, Alistair (1992). "The Green Party in England and Wales: Structure and Development: The Early Years". Environmental Politics. 1 (3): 418–436. doi:10.1080/09644019208414033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pattie, C. J.; Russell, A. T.; Johnston, R. J. (1991). "Going Green in Britain ? Votes for the Green Party and Attitudes to Green Issues in the Late 1980s". Journal of Rural Studies. 7 (3): 285–297. doi:10.1016/0743-0167(91)90091-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rootes, Chris (1995). "Britain: Greens in a Cold Climate". The Green Challenge: The Development of Green Parties in Europe. Dick Richardson and Chris Rootes. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 66–90.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Carter, Neil (2015). "The Greens in the UK general election of 7 May 2015". Environmental Politics. 24 (6): 1055–1060. doi:10.1080/09644016.2015.1063750.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dennison, James (2016). The Greens in British Politics: Protest, Anti-Austerity and the Divided Left. Palgrave.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maciejowska, Judy (2017). "For the Common Good: The Green Party's 2015 General Election Campaign". In Dominic Wring; Roger Mortimore; Simon Atkinson (eds.). Political Communication in Britain: Polling, Campaigning and Media in the 2015 General Election. Springer. pp. 169–179. ISBN 978-3-319-40933-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, Ceri (2016). "It's not easy (not) being green: Agenda dissonance of Green Party press relations and newspaper coverage". European Journal of Communication. 31 (6): 625–641. doi:10.1177/0267323116669454.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)