Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central Terminal (GCT; also referred to as Grand Central Station[N 2] or simply as Grand Central) is a commuter rail terminal located at 42nd Street and Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Grand Central is the southern terminus of the Metro-North Railroad's Harlem, Hudson and New Haven Lines, serving the northern parts of the New York metropolitan area. It also contains a connection to the New York City Subway at Grand Central–42nd Street station. The terminal is the third-busiest train station in North America, after New York Penn Station and Toronto Union Station.

Grand Central Terminal  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro-North Railroad terminal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Clockwise from top left: 42nd Street facade; underground train shed and tracks; Main Concourse; iconic clock atop the information booth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | 89 East 42nd Street (at Park Avenue) Manhattan, New York City | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operated by |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | Park Avenue Tunnel (Hudson Line) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 44: 43 island platforms, 1 side platform (6 tracks with Spanish solution) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 67: 56 passenger tracks (30 on upper level, 26 on lower level) 43 in use for passenger service 11 sidings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connections | MTA New York City Subway: at Grand Central–42nd Street | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platform levels | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disabled access | Accessible[N 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Official website | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key dates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | 1903–1913 Opened February 2, 1913 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traffic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Passengers (FY 2017) | 66,952,732 Annually, based on weekly estimate[2] (Metro-North) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactive map | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°45′10″N 73°58′38″W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect | Reed and Stem; Warren and Wetmore | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style(s) | Beaux-Arts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Visitors | 21.6 million (in 2018)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated | December 8, 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reference no. | 75001206 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated | January 17, 1975 August 11, 1983 (increase) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reference no. | 75001206, 83001726 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

New York City Landmark | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated | August 2, 1967 September 23, 1980 (interior) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reference no. | LP-0266, LP-1099 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The distinctive architecture and interior design of Grand Central Terminal's station house have earned it several landmark designations, including as a National Historic Landmark. Its Beaux-Arts design incorporates numerous works of art. Grand Central Terminal is one of the world's ten most visited tourist attractions,[4] with 21.6 million visitors in 2018, excluding train and subway passengers.[3] The terminal's main concourse is often used as a meeting place, and is especially featured in films and television. Grand Central Terminal contains a variety of stores and food vendors, including a food court on its lower-level concourse.

Grand Central Terminal was built by and named for the New York Central Railroad; it also served the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and, later, successors to the New York Central. Opened in 1913, the terminal was built on the site of two similarly-named predecessor stations, the first of which dates to 1871. Grand Central Terminal served intercity trains until 1991, when Amtrak began routing its trains through nearby Penn Station. The East Side Access project, which will bring Long Island Rail Road service to a new station beneath the terminal, is expected to be completed in late 2022.

Grand Central covers 48 acres (19 ha) and has 44 platforms, more than any other railroad station in the world. Its platforms, all below ground, serve 30 tracks on the upper level and 26 on the lower. In total, there are 67 tracks, including a rail yard and sidings; of these, 43 tracks are in use for passenger service, while the remaining two dozen are used to store trains.[N 3] Another eight tracks and four platforms are being built on two new levels deep underneath the existing station as part of East Side Access.

Name

Grand Central Terminal was named by and for the New York Central Railroad, which built the station and its two precursors on the site. It has "always been more colloquially and affectionately known as Grand Central Station", the name of its immediate precursor[5][6][N 2] that operated from 1900[8] until 1910.[9] The name "Grand Central Station" is also shared with the nearby U.S. Post Office station at 450 Lexington Avenue[10] and, colloquially, with the Grand Central–42nd Street station next to the terminal.[11]

Services

Commuter rail

Grand Central Terminal serves some 67 million passengers a year, more than any other Metro-North station.[2][12] At morning rush hour, a train arrives at the terminal every 58 seconds.[13]

Three of Metro-North's five main lines terminate at Grand Central:[14]

- Harlem Line to Wassaic, New York

- Hudson Line to Poughkeepsie, New York (Amtrak connection to Albany)

- New Haven Line to New Haven, Connecticut (Amtrak connection to Hartford, Springfield, Boston; Shore Line East to New London)

- New Canaan Branch to New Canaan, Connecticut

- Danbury Branch to Danbury, Connecticut

- Waterbury Branch to Waterbury, Connecticut

Through these lines, the terminal serves Metro-North commuters traveling to and from the Bronx in New York City; Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess counties in New York; and Fairfield and New Haven counties in Connecticut.[14]

Connecting services

The New York City Subway's adjacent Grand Central–42nd Street station serves the following routes:[11]

- 4, 5, 6, and <6> trains (IRT Lexington Avenue Line), situated diagonally under the Pershing Square Building/110 East 42nd Street, 42nd Street, and Grand Hyatt New York

- 7 and <7> trains (IRT Flushing Line), under 42nd Street between Park Avenue and west of Third Avenue

- S train (42nd Street Shuttle), under 42nd Street between Madison Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue

These MTA Regional Bus Operations buses stop near Grand Central:[1][15]

- NYCT Bus:

- M1, M2, M3, M4 and Q32 local buses at Madison Avenue (northbound) and Fifth Avenue (southbound)

- X27, X28, X37, X38, SIM4C, SIM6, SIM8, SIM8X, SIM11, SIM22, SIM25, SIM26, SIM30, SIM31 and SIM33C express buses at Madison Avenue (northbound)

- X27, X28, X37, X38, SIM4C, SIM8, SIM8X, SIM25, SIM31 and SIM33C express buses at Fifth Avenue (southbound)

- M42 local bus at 42nd Street

- M101, M102 and M103 local buses at Third Avenue (northbound) and Lexington Avenue (southbound)

- X27, X28, X63, X64 and X68 express buses at Third Avenue (northbound)

- SIM6, SIM11, SIM22 and SIM26 express buses at Lexington Avenue (southbound)

- MTA Bus:

- BxM3, BxM4, BxM6, BxM7, BxM8, BxM9, BxM10, BxM18, BM1, BM2, BM3, BM4 and BM5 express buses at Madison Avenue (northbound) and Fifth Avenue (southbound)

- BxM1 express bus at Lexington Avenue (southbound)

- BxM1, QM21, QM31, QM32, QM34, QM35, QM36, QM40, QM42 and QM44 express buses at Third Avenue (northbound)

- Academy Bus:

- SIM23 and SIM24 express buses at Madison Avenue (northbound) and Fifth Avenue (southbound)

Former services

The terminal and its predecessors were designed for intercity service, which operated from the first station building's completion in 1871 until Amtrak ceased operations in the terminal in 1991. Through transfers, passengers could connect to all major lines in the United States, including the Canadian, the Empire Builder, the San Francisco Zephyr, the Southwest Limited, the Crescent, and the Sunset Limited under Amtrak. Destinations included San Francisco, Los Angeles, Vancouver, New Orleans, Chicago, and Montreal.[16] Another notable former train was New York Central's 20th Century Limited, a luxury service that operated to Chicago's LaSalle Street Station between 1902 and 1967 and was among the most famous trains of its time.[17][18]

From 1971 to 1991, all Amtrak trains using the intrastate Empire Corridor to Niagara Falls terminated at Grand Central; interstate Northeast Corridor trains used Penn Station.[19] Notable Amtrak services at Grand Central included the Lake Shore, Empire Service, Ethan Allen Express, Adirondack, Niagara Rainbow, Maple Leaf, and Empire State Express.[20][21][22]

Planned services

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority plans to bring Long Island Rail Road commuter trains to a new station beneath Grand Central as part of its East Side Access project.[23] The project will connect the terminal to the railroad's Main Line,[24] which connects to all of the LIRR's branches and almost all of its stations.[25] As of 2018, service is expected to begin in late 2022.[26][27]

Interior

Grand Central Terminal was designed and built with two main levels for passengers: an upper for intercity trains and a lower for commuter trains. This configuration, devised by New York Central vice president William J. Wilgus, separated intercity and commuter-rail passengers, smoothing the flow of people in and through the station. After intercity service ended in 1991,[28] the upper level was renamed the Main Concourse and the lower the Dining Concourse.[28][29]

The original plan for Grand Central's interior was designed by Reed and Stem, with some work by Whitney Warren of Warren and Wetmore.[30][31]

Grand Central Terminal's 48-acre (19 ha) basements are among the largest in the city.[32]

Main Concourse

The Main Concourse, originally known as the Express Concourse, is located on the upper platform level of Grand Central, in the geographical center of the station building. The 35,000-square-foot (3,300 m2) concourse[33] leads directly to most of the terminal's upper-level tracks, although some are accessed from passageways near the concourse.[34] The Main Concourse is usually filled with bustling crowds and is often used as a meeting place.[35]

The terminal's ticket booths are located in the Main Concourse, although many have been closed or repurposed since the introduction of ticket vending machines. The concourse's large American flag was installed there a few days after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.[35][7] The Main Concourse is surrounded on most of its sides by balconies. The east side is occupied by an Apple Store, while the west side is occupied by the Italian restaurant Cipriani Dolci (part of Cipriani S.A.), the Campbell Palm Court, and the Campbell Bar, a former financier's office-turned-bar.[34] Underneath the east and west balconies are entrances to Grand Central's passageways, with shops and ticket machines along the walls.[36]

Information booth and clock

The 18-sided main information booth — originally the "information bureau" — is in the center of the concourse. Its attendants provide train schedules and other information to the public;[37] in 2015, they fielded more than 1,000 questions an hour, according to an MTA spokesman.[38] A door within the marble and brass pagoda conceals a spiral staircase down to a similar booth on the station's Dining Concourse.[39][40][38]

The booth is topped by a four-faced brass clock, one of Grand Central's most recognizable icons according to a book by the New York Transit Museum.[41] The clock was designed by Henry Edward Bedford, cast in Waterbury, Connecticut,[35] and designed by the Self Winding Clock Company and built by the Seth Thomas Clock Company, along with several other clocks in the terminal.[42][7] Each 24-inch (61 cm) face[39] is made from opalescent glass, now often called opal glass or milk glass. However, urban legend says the faces are actually opal, valued by Sotheby's or Christie's between $10 million and $20 million.[43] The clock was first stopped for repairs in 1954, after it was found to be losing a minute or two per day.[44]

Along with the rest of the New York Central Railroad system's clocks, it was formerly set to a clock in the train dispatcher's office at Grand Central.[45] Through the 1980s, they were set to a master clock at a workshop in Grand Central.[46] Since 2004, they have been set to the United States Naval Observatory's atomic clock, accurate to a billionth of a second.[47][38]

Departure and gate boards

The terminal's primary departure board is located on the south side of the concourse, installed directly atop the two sets of ticket windows. Colloquially known as the "Big Board", it shows the track and status of arriving and departing trains.[48][49]

There have been five departure boards used over the terminal's history: the 1913–1967 chalkboard, the 1967–1985 Solari board, the 1985–1996 Omega board, the 1996–2019 LCD board, and the 2019 fully digital display. For the first 54 years of the terminal's operation, train arrival and departure information was hand-chalked on a blackboard in the Biltmore Room. In 1967, the blackboard was supplanted by an electromechanical display in the main concourse over the ticket windows;[50][51] the original chalkboard remains as a relic in the Biltmore Room. Dubbed a Solari board after its Italian manufacturer Solari di Udine, it displayed train information on rows of flip panels that made a distinctive flapping sound as they rotated to reflect changes.[48][49] In 1985, the Solari board was replaced with the Omega board, designed and installed by Advanced Computer Systems of Dayton, Ohio, and named for its manufacturer, watchmaker Omega SA.[52] This board was removed during a terminal renovation in July 1996; it was replaced several months later with a liquid-crystal display[51] that replicated the analog look of the older boards and which was the first installed over both the east and the west ticket offices.[53] Between March and September 2019,[54] the LCD boards were replaced by LED video wall screens installed in the existing housing.[53][55][56][54] Designed by the MTA and New York's State Historic Preservation Office, the displays are brighter and easier to read, ADA-compliant, are the first to display real-time updates,[57] and are necessary because the old equipment's software was no longer available.[58] Commuter complaints about the new displays were published in the news, as had complaints over the three prior board replacements, in 1967, 1985, and 1996.[53][50][59]

• 1913–1967 train gate display

• 1967–1985 Solari gate display (out of cabinetry)

• 1996–present LCD displays

• 2019–present fully digital displays

There are also arrival and departure displays at each of the platform gates, about 93 in total.[56] Originally these were cloth curtains with train information stitched onto them, posted at the platform entrances.[52] The signs were eventually replaced with flip panels, replaced again with the installation of the Omega Board in 1987,[52] and supplanted again by LCD panels, which are being replaced between 2017 and 2020.[60][54]

Uses

The size of the Main Concourse has made it an ideal advertising space.[61] During World War II, a large mural with images of the United States military hung in the concourse,[61] and from the 1950s to 1989, the Kodak Colorama exhibit was a prominent fixture.[62][63][64] A thirteen-and-a-half-foot-diameter (4.1 m) illuminated clock hung in the Main Concourse at the entrance to the main waiting room from the 1960s to the 1990s. The clock, sometimes referred to as "Big Ben", had chimes, and after 1986, news and stock information. The clock was sponsored by at least five companies; its first and most significant was Westclox.[65][66] All of these advertisements and fixtures were removed around the time of the terminal's renovation in the 1990s; only four advertisement screens remain on the concourse, each about 7 x 6 feet.[67]

The Main Concourse has also been used as a gathering venue. In the 1960s, the terminal's tenant CBS installed a CBS News television screen above the ticket offices to follow the spaceflights of Project Mercury;[68] thousands would gather in the Main Concourse to watch key events of the flights.[69][70][71] Politicians such as U.S. presidents Calvin Coolidge and Harry S. Truman; presidential candidates Thomas Dewey and Robert F. Kennedy; and governor Herbert Lehman have also held events within the concourse.[72] The Main Concourse has also been used for memorials, including events to commemorate U.S. ambassador to France Myron T. Herrick and former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis after their deaths; celebrations for Martin Luther King Jr. Day; and an impromptu memorial created after the September 11 attacks in 2001.[73] Several celebrations have also taken place at the terminal, such as a celebration for the New York Giants after they won the NFL championship in 1933;[74] an event for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1941;[74][75] and several large parties and New Year's celebrations.[74][76]

Various special exhibits and events have also been held at the Main Concourse throughout the years.[77]

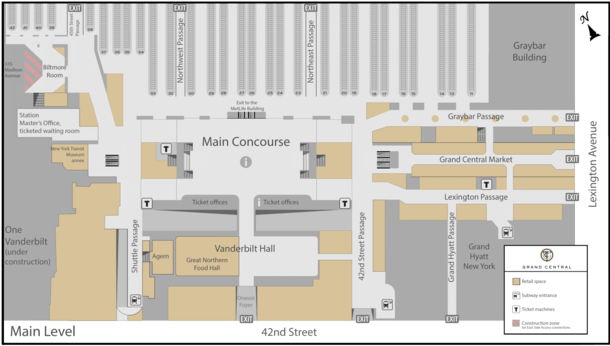

Passageways

In their design for the station's interior, Reed & Stem created a circulation system that allowed passengers alighting from trains to enter the Main Concourse, then leave through various passages that branch from it.[78] Among these are the north–south 42nd Street Passage and Shuttle Passage, which run south to 42nd Street; and three east–west passageways — the Grand Central Market, the Graybar Passage, and the Lexington Passage — that run about 240 feet east to Lexington Avenue by 43rd Street.[34][79] Several passages run north of the terminal, including the north–south 45th Street Passage, which leads to 45th Street and Madison Avenue,[80] and the network of tunnels in Grand Central North, which lead to exits at every street from 45th to 48th Street.[34]

Each of the east–west passageways runs through a different building. The northernmost is the Graybar Passage,[34] built on the first floor of the Graybar Building in 1926.[81] Its walls and seven large transverse arches are made of coursed ashlar travertine, and the floor is terrazzo. The ceiling is composed of seven groin vaults, each of which has an ornamental bronze chandelier. The first two vaults, as viewed from leaving Grand Central, are painted with cumulus clouds, while the third contains a 1927 mural by Edward Trumbull depicting American transportation.[82][83]

The middle passageway houses Grand Central Market, a cluster of food shops.[34][84] The site was originally a segment of 43rd Street which became the terminal's first service dock in 1913.[85] In the mid-1970s, a savings bank was built in the space,[86] which was converted into the marketplace in 1998, and involved installing a new limestone facade on the building.[87] The building's second story, whose balcony overlooks the market and 43rd Street, was to house a restaurant, but is instead used for storage.[79][88]

The southernmost of the three, the Lexington Passage, was originally known as the Commodore Passage after the Commodore Hotel, which it ran through.[79] When the hotel was renamed the Grand Hyatt, the passage was likewise renamed. The passage acquired its current name during the terminal's renovation in the 1990s.[87]

Grand Central North

Grand Central North is a network of four tunnels that allow people to walk between the station building (which sits between 42nd and 44th Street) and exits at 45th, 46th, 47th, and 48th Street.[89] The 1,000-foot (300 m) Northwest Passage and 1,200-foot (370 m) Northeast Passage run parallel to the tracks on the upper level, while two shorter cross-passages run perpendicular to the tracks.[90][91] The 47th Street cross-passage runs between the upper and lower tracks, 30 feet (9.1 m) below street level; it provides access to upper-level tracks. The 45th Street cross-passage runs under the lower tracks, 50 feet (15 m) below street level. Converted from a corridor built to transport luggage and mail,[91] it provides access to lower-level tracks.

The tunnels' street-level entrances, each enclosed by a freestanding glass structure,[91] sit at the northeast corner of East 47th Street and Madison Avenue (Northwest Passage), northeast corner of East 48th Street and Park Avenue (Northeast Passage), on the east and west sides of 230 Park Avenue (Helmsley Building) between 45th and 46th Streets, and (since 2012) on the south side of 47th Street between Park and Lexington Avenues.[92] Pedestrians can also take an elevator to the 47th Street passage from the north side of East 47th Street, between Madison and Vanderbilt Avenues.[93]

Proposals for these tunnels had been discussed since at least the 1970s. The MTA approved preliminary plans in 1983,[94] gave final approval in 1991,[95] and began construction in 1994.[90] Dubbed the North End Access Project, the work was to be completed in 1997 at a cost of $64.5 million,[95] but it was slowed by the incomplete nature of the building's original blueprints and by previously undiscovered groundwater beneath East 45th Street.[90] The passageways opened on August 18, 1999, at a final cost of $75 million.[90]

The passages contain an MTA Arts & Design mosaic installation by Ellen Driscoll, an artist from Brooklyn.[90]

The entrances to Grand Central North were originally open from 6:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. Monday through Friday and 9 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. About 6,000 people used the passages on a typical weekend,[96] and about 30,000 on weekdays. Since summer 2006, Grand Central North has been closed on weekends; MTA officials cited low usage and the need to save money.[97]

Other spaces on the main floor

Vanderbilt Hall

Vanderbilt Hall is an event space on the south side of the terminal, between the Park Avenue entrance located to its south and the Main Concourse located to its north. Its west side houses a food hall.[34] The space is lit by Beaux-Arts chandeliers, each with 132 bulbs on four tiers.[98]

It was formerly the main waiting room for the terminal, used particularly by intercity travelers. The space featured double-sided oak benches and could seat 700 people.[99] When intercity service ceased at Grand Central in 1991, the room began to be used by several hundred homeless people. Terminal management responded first by removing the room's benches, then by closing the space entirely.[N 4] In 1998, the hall was renovated and renamed Vanderbilt Hall after the family that built and owned the station.[79] It is used for the annual Christmas Market,[101] as well as for special exhibitions and private events.[102]

Since 1999, Vanderbilt Hall has hosted the annual Tournament of Champions squash championship.[103] Each January, tournament officials construct a free-standing glass-enclosed 21-by-32-foot (6.4 by 9.8 m) squash court. Like a theatre in the round, spectators sit on three sides of the court.[104]

In 2016, the west half of the hall became the Great Northern Food Hall, an upscale Nordic-themed food court with five pavilions. The food hall is the first long-term tenant of the space; the terminal's landmark status prevents permanent installations.[105]

A men's smoking room and women's waiting room were formerly located on the west and east sides of Vanderbilt Hall, respectively.[105] In 2016, the men's room was renovated into Agern, an 85-seat Nordic-themed fine dining and Michelin-starred restaurant operated by Noma co-founder Claus Meyer,[106] who also runs the food hall.[105]

Biltmore Room

The Biltmore Room is a 64-by-80-foot (20 by 24 m) marble hall[107] northwest of the Main Concourse that serves as an entrance to tracks 39 through 42.[34] Completed in 1915[108] directly beneath the New York Biltmore Hotel,[107] it originally served as a waiting room for intercity trains known formally as the incoming train room and colloquially as the "Kissing Room".[108]

As the station's passenger traffic declined in mid-century, the room fell into neglect. In 1982 and 1983, the room was damaged during the construction that converted the Biltmore Hotel into the Bank of America Plaza. In 1985, Giorgio Cavaglieri was hired to restore the room, which at the time had cracked marble and makeshift lighting. During that era, a series of lockers was still located within the Biltmore Room.[109] Later, the room held a newsstand, flower stand, and shoe shine booths.[108][110] In 2015, the MTA awarded a contract to refurbish the Biltmore Room into an arrival area for Long Island Rail Road passengers as part of the East Side Access project.[111] As part of the project, the room's booths and stands are to be replaced by a pair of escalators and an elevator to the deep-level LIRR concourse.[108][110]

The room's blackboard displayed the arrival and departure times of New York Central trains until 1967,[50] when a mechanical board was installed in the Main Concourse.[107]

Station Master's Office

The Station Master's Office, located near Track 36, has Grand Central's only dedicated waiting room. The space has benches, restrooms, and a floral mixed-media mural on three of its walls. The room's benches were previously located in the former waiting room, now known as Vanderbilt Hall. Since 2008, the area has offered free Wi-Fi.[112]

Former theatre

One of the retail areas of the Graybar Passage, currently occupied by wine and liquor store Central Cellars, was the Grand Central Theatre or Terminal Newsreel Theatre.[113][114] Opened in 1937, the theater showed short films, cartoons, and newsreels[115] continuously from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m. for 25-cent tickets.[116][117] Designed by Tony Sarg, it had 242 stadium-style seats and a standing-room section with armchairs. A small bar sat near the entrance.[118] The theater's interior had simple pine walls spaced out to eliminate echos, along with an inglenook, a fireplace, and an illuminated clock for the convenience of travelers. The walls of the lobby, dubbed the "appointment lounge", were covered with world maps; the ceiling had an astronomical mural painted by Sarg.[113] The New York Times reported a cost of $125,000 for the theater's construction, which was attributed to construction of an elevator between the theater and the suburban concourse as well as air conditioning and apparatuses for people hard of hearing.[117]

The theater stopped showing newsreels by 1968[119] but continued operating until around 1979, when it was gutted for retail space.[116] A renovation in the early 2000s removed a false ceiling, revealing the theater's projection window and its astronomical mural, which proved similar in colors and style to the Main Concourse ceiling.[115]

Dining Concourse

Access to the lower-level tracks is provided by the Dining Concourse, below the Main Concourse and connected to it by numerous stairs, ramps, and escalators. For decades, it was called the Suburban Concourse because it handled commuter rail trains.[29] Today, it has central seating and lounge areas, surrounded by restaurants and food vendors.[34] The shared public seating in the concourse was designed resembling Pullman traincars.[79] These areas are frequented by the homeless, and as a result, in the mid-2010s the MTA created two areas with private seating for dining customers.[120]

The concourses are connected by two ramps, which comprise a 302-foot (92 m) west–east axis under an 84-foot (26 m) ceiling.[121] They intersect a slight slope from the Dining Concourse just outside the Oyster Bar,[34] under an archway covered with Guastavino tiling.[122] The arch creates a whispering gallery: someone standing in one corner can hear someone speaking softly in the diagonally opposite corner.[68][43] An overpass between the main concourse and the Vanderbilt Hall passes over the archway; from 1927 until 1998, the sides of the overpass were enclosed by walls about 8 feet (2.4 m) high.[121]

As part of the terminal's late-1990s renovation, stands and restaurants were installed in the concourse, and escalators added to link to the main concourse level.[79] Additionally, the MTA spent $2.2 million to construct two 45-foot-wide circular designs in the concourse's floor. The designs were by David Rockwell and Beyer Blinder Belle, made of terrazzo, and installed over the concourse's original terrazzo floor.[123] Since 2015, part of the Dining Concourse has been closed for the construction of structural framework to support stairways and escalators to the new LIRR terminal being built as part of East Side Access.[124]

A small square-framed clock is installed in the ceiling near Tracks 108 and 109. It was manufactured at an unknown time by the Self Winding Clock Company, which made several others in the terminal. The clock hung inside the gate at Track 19 until 2011, when it was moved so it would not be blocked by lights added during upper-level platform improvements.[42]

Lost-and-found bureau

Metro-North's lost-and-found bureau sits near Track 100 at the far east end of the Dining Concourse. Incoming items are sorted according to function and date: for instance, there are separate bins for hats, gloves, belts, and ties.[125][126] The sorting system was computerized in the 1990s.[127] Lost items are kept for up to 90 days before being donated or auctioned off.[43][128]

As early as 1920, the bureau received between 15,000 and 18,000 items a year.[129] By 2002, the bureau was collecting "3,000 coats and jackets; 2,500 cellphones; 2,000 sets of keys; 1,500 wallets, purses and ID's [sic]; and 1,100 umbrellas" a year.[127] By 2007, it was collecting 20,000 items a year, 60% of which were eventually claimed.[128] In 2013, the bureau reported an 80% return rate, among the highest in the world for a transit agency.[43][38]

Some of the more unusual items collected by the bureau include fake teeth, prosthetic body parts, legal documents, diamond pouches, live animals, and a $100,000 violin.[126][128] One story has it that a woman purposely left her unfaithful husband's ashes on a Metro-North train before collecting them three weeks later.[43][128] In 1996, some of the lost-and-found items were displayed at an art exhibition.[130]

Other food service and retail spaces

Grand Central Terminal contains restaurants such as the Grand Central Oyster Bar & Restaurant and various fast food outlets surrounding the Dining Concourse. There are also delis, bakeries, a gourmet and fresh food market, and an annex of the New York Transit Museum.[131][132] The 40-plus retail stores include newsstands and chain stores, including a Starbucks coffee shop, a Rite Aid pharmacy, and an Apple Store.[34][133]

The Oyster Bar, the oldest business in the terminal, sits next to the Dining Concourse and below Vanderbilt Hall.[34][105]

An elegantly restored cocktail lounge, the Campbell, sits just south of the 43rd Street/Vanderbilt Avenue entrance. A mix of commuters and tourists access it from the street or the balcony level.[34] The space was once the office of 1920s tycoon John W. Campbell, who decorated it to resemble the galleried hall of a 13th-century Florentine palace.[134][135] In 1999, it opened as a bar, the Campbell Apartment; a new owner renovated and renamed it the Campbell in 2017.[136]

Vanderbilt Tennis Club and former studios

From 1939 to 1964, CBS Television occupied a large portion of the terminal building, particularly in a fourth-floor space above Vanderbilt Hall.[137][138] The CBS offices, called "The Annex",[138] contained two "program control" facilities (43 and 44); network master control; facilities for local station WCBS-TV;[137][138][139] and, after World War II, two 700,000-square-foot (65,000 m2) production studios (41 and 42).[140] Broadcasts were transmitted from an antenna atop the nearby Chrysler Building installed by order of CBS chief executive William S. Paley,[140][139] and were also shown on a large screen in the Main Concourse.[140] In 1958, CBS opened the world's first major videotape operations facility in Grand Central. Located in a former rehearsal room on the seventh floor, the facility used 14 Ampex VR-1000 videotape recorders.[137][138]

Douglas Edwards with the News broadcast from Grand Central for several years, covering John Glenn's 1962 Mercury-Atlas 6 space flight and other events. Edward R. Murrow's See It Now originated there, including his famous broadcasts on Senator Joseph McCarthy, which were recreated in George Clooney's movie Good Night, and Good Luck, although the film incorrectly implies that CBS News and corporate offices were in the same building. The long-running panel show What's My Line? was first broadcast from Grand Central, as were The Goldbergs and Mama. CBS eventually moved its operations to the CBS Broadcast Center.[137][138][140]

In 1966, the vacated studio space was converted into the Vanderbilt Tennis Club, a sports club named for the hall just below.[137][138][141][142] Founded by Geza A. Gazdag, an athlete and Olympic coach who fled Hungary amid its 1956 revolution,[143] its two tennis courts were once deemed the most expensive place to play the game—$58 an hour—until financial recessions forced the club to lower the hourly fee to $40.[144] In 1984, the club was purchased by real estate magnate Donald Trump, who discovered it while renovating the terminal's exterior[145] and operated it until 2009.[137] The space is currently occupied by a conductor lounge and a smaller sports facility with a single tennis court.[138][142]

Basement spaces

Power and heating plant

Grand Central Terminal and its predecessors contained their own power plants. The first such plant, built for Grand Central Depot in the 1870s, stood in the surface-level railroad yards at Madison Avenue and 46th Street. The second was built in 1900 under the west side of Grand Central Station near 43rd Street.[146]

When the terminal was created, a new power and heating plant was built on the east side of Park Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets.[147][148] The two-smokestack structure could supply a daily average of 5,000,000 pounds (2,300,000 kg) of heating steam.[146][149] The plant also provided power to the tracks and the station, supplementing other New York Central power plants in Yonkers (later renamed the Glenwood Power Station) and Port Morris in the Bronx (since demolished).[146] While the Port Morris and Yonkers plants provided 11,000-volt alternating current for arriving and departing locomotives, the Grand Central plant converted the alternating current to 800 volts of direct current for use by the terminal's own third-rail-powered locomotives.[146][150] In addition, the Grand Central power plant provided power to nearby buildings.[148][146]

By the late 1920s, most power and heating services were contracted out to Consolidated Edison,[151] and so the power plant was torn down in 1929.[152] Its only remaining vestige is the storage yard under the Waldorf Astoria New York hotel built in 1931.[148] A new substation—the world's largest at the time—was built 100 feet (30 m) under the Graybar Building at a cost of $3 million.[146][153] Occupying a four-story space with an area of 250 by 50 feet (76 by 15 m),[146][151] it is divided into substation 1T, which provides 16,500 kilowatts (22,100 hp) for third-rail power, and substation 1L, which provides 8,000 kilowatts (11,000 hp) for other lighting and power.[146]

A sub-basement, dubbed M42, contains the AC-to-DC converters that supply DC traction current to the tracks.[43] Though sources vary on its exact depth, it is thought to be located 105 to 109 feet (32 to 33 m) below ground,[154] or either 10 or 13 stories deep.[155] The M42 basement was installed in the former boiler void excavated in the bedrock beneath the present-day Grand Central Market and the entrance to the Graybar Building, three levels below the lower Metro-North level.[156] Two of the original rotary converters remain as a historical record. During World War II, this facility was closely guarded because its sabotage would have impaired troop movement on the Eastern Seaboard.[32][157][158] It is said that any unauthorized person entering the facility during the war risked being shot on sight; the rotary converters could have easily been crippled by a bucket of sand.[159] The Abwehr, a German espionage service, sent two spies to sabotage it; they were arrested by the FBI before they could strike.[32] M42 also included a system to monitor trains in and around the terminal, which was used from 1913 until 1922, when it was supplemented by telegraphs.[43]

Carey's Hole

Another part of the basement is known as Carey's Hole. The two-story section is directly beneath the Shuttle Passage and adjacent spaces. In 1913, when the terminal opened, J. P. Carey opened a barbershop adjacent to and one level below the terminal's waiting room (now Vanderbilt Hall). Carey's business expanded to include a laundry service, shoe store, and haberdashery. In 1921, Carey also ran a limousine service using Packard cars, and in the 1930s, he added regular car and bus service to the city's airports as they opened. Carey would store his merchandise in an unfinished, underground area of the terminal, which railroad employees and maintenance staff began calling "Carey's Hole". The name has remained even as the space has been used for different purposes, including currently as a lounge and dormitory for railroad employees.[160]

Platforms and tracks

The terminal holds the Guinness World Record for having the most platforms of any railroad station:[161] 28, which support 44 platform numbers. All are island platforms except one side platform.[162] Odd-numbered tracks are usually on the east side of the platform; even-numbered tracks on the west side. As of 2016, there are 67 tracks, of which 43 are in regular passenger use, serving Metro-North.[163][164] At its opening, the train shed contained 123 tracks, including duplicate track numbers and storage tracks,[164] with a combined length of 19.5 miles (31.4 km).[165]

The tracks slope down as they exit the station to the north, to help departing trains accelerate and arriving ones slow down.[166] Because of the size of the rail yards, Park Avenue and its side streets from 43rd Street to 59th Street are raised on viaducts, and the surrounding blocks were covered over by various buildings.[167]

At its busiest, the terminal is served by an arriving train every 58 seconds.[38]

Track distribution

Grand Central track map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Metro-North upper level | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Metro-North lower level | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LIRR upper level (future) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LIRR lower level (future) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Map not to scale. Source:[168][169] For further details on the Metro-North track layout north of 59th Street, see Park Avenue main line#Line description.[170] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The upper Metro-North level has 42 numbered tracks. Twenty-nine serve passenger platforms; these are numbered 11 to 42, east to west.[165][168] Tracks 12, 22, and 31 do not exist, and appear to have been removed.[169] To the east of the upper platforms sits the East Yard: ten storage tracks numbered 1 through 10 from east to west.[168][164] A balloon loop runs from Tracks 38–42 on the far west side of the station, around the other tracks, and back to storage Tracks 1–3 at the far east side of the station;[168] this allows trains to turn around more easily.[171][172]

North of the East Yard is the Lex Yard, a secondary storage yard under the Waldorf Astoria Hotel.[168] The yard formerly served the power plant for Grand Central Terminal.[148] Its twelve tracks are numbered 51 through 65 from east to west (track numbers 57, 58, and 62 do not exist). Two private loading platforms, which cannot be used for passenger service, sit between tracks 53 and 54 and between tracks 61 and 63.[168] Track 61 is known for being a private track for United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt; part of the original design of the Waldorf Astoria,[173] it was mentioned in The New York Times in 1929 and first used in 1938 by John J. Pershing, a top U.S. general during World War I.[174] Roosevelt would travel into the city using his personal train, pull into Track 61, and take a specially designed elevator to the surface.[175] It has been used occasionally since Roosevelt's death.[176][177] The upper level also contains 22 more storage sidings.[165][168]

The lower Metro-North level has 27 tracks numbered 100 to 126, east to west.[168][164][178] Two were originally intended for mail trains and two were for baggage handling.[28][29] Today, only Tracks 102–112 and 114–115 are used for passenger service. The lower-level balloon loop, whose curve was much sharper than that of the upper-level loop and could only handle electric multiple units used on commuter lines[179] was removed at an unknown date.[164] Tracks 116–125 were demolished to make room for the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) concourse being built under the Metro-North station as part of the East Side Access project.[180]

The upper and lower levels have different track layouts and, as such, are supported by different sets of columns. The upper level is supported by ultra-strong columns, some of which can carry over 7,000,000 foot-pounds force (9,500,000 J).[181]

The LIRR terminal being built as part of East Side Access will add four platforms and eight tracks numbered 201–204 and 301–304 in two 100-foot-deep (30 m) double-decked caverns below the Metro-North station.[182] The new LIRR station will have four tracks and two platforms in each of the two caverns, with each cavern containing two tracks and one platform on each level. A mezzanine will sit on a center level between the LIRR's two track levels.[183][184]

Control center

Grand Central Terminal was built with five signal control centers, labeled A, B, C, F, and U, that collectively controlled all of the track interlockings around the terminal. Each switch was electrically controlled by a lever in one of the signal towers, where lights illuminated on track maps to show which switches were in use.[185][179] As trains passed a given tower, the signal controllers reported the train's engine and timetable numbers, direction, track number, and the exact time.[186]

Tower U controlled the interlocking between 48th and 58th Streets; Tower C, the storage spurs; and Tower F, the turning loops. A four-story underground tower at 49th Street housed the largest of the signal towers: Tower A, which handled the upper-level interlockings via 400 levers, and Tower B, which handled the lower-level interlockings with 362 levers.[187][188][189][179][190] The towers housed offices for the stationmaster, yardmaster, car-maintenance crew, electrical crew, and track-maintenance crew. There were also break rooms for conductors, train engineers, and engine men.[189][185]

After Tower B was destroyed in a fire in 1986,[191] the signal towers were consolidated into a single Operations Control Center, where controllers could monitor the switches by computer. Completed in 1993,[192] the center is operated by a crew of 24 people.[193]

Hospital

During the terminal's construction, an "accident room" was set up to treat worker injuries in a wrecking car in the terminal's rail yard. Later on, a small hospital was established in the temporary station building on Lexington Avenue to care for injured workers. The arrangement was satisfactory, leading to the creation of a permanent hospital, the Grand Central Emergency Hospital, in Grand Central Terminal in 1911. The hospital was used for every employee injury as well as for passengers. In 1915, it had two physicians who treated a monthly average of 125 new cases per month and 450 dressings.[194] The space had four rooms: Room A (the waiting room), Room B (the operating room), Room C (a private office), and Room D (for resting patients).[195] The hospital was open at least until 1963; a Journal News article that year noted that the hospital treated minor to moderate ailments and was open every day between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m.[196]

Libraries

Located on an upper floor above the Apple Store, the Williamson Library is a meeting space and research center for the New York Railroad Enthusiasts.[197][198] Upon its founding in 1937, the association was granted use of the space in perpetuity by Frederick Ely Williamson, once president of the New York Central Railroad as well as a rail enthusiast and member of the association.[197] Today, it contains about 3,000 books, newspapers, films, photographs, and other documents about railroads, along with artifacts, including part of a 20th Century Limited red carpet.[198] The library is only accessible through secure areas, making it little known to the public and not included in tours of the terminal's hidden attributes.[198] The association holds monthly meetings in the space, open to new visitors for free, and allows research visits by appointment.[199][200]

Another library, the Frank Julian Sprague Memorial Library of the Electric Railroaders Association, was created in the terminal in 1979. The library has about 500,000 publications and slides, focusing on electric rail and trolley lines.[200] A large amount of these works were donated to the New York Transit Museum in 2013.[201]

Architecture

Grand Central Terminal was designed in the Beaux-Arts style by Reed and Stem, which was responsible for the overall design of the terminal,[78] and Warren and Wetmore, which mainly made cosmetic alterations to the exterior and interior.[202][203][204] Various elements inside the terminal were designed by French architects and artists Jules-Félix Coutan, Sylvain Salières, and Paul César Helleu.[204] Grand Central has both monumental spaces and meticulously crafted detail, especially on its facade.[205] The facade is based on an overall exterior design by Whitney Warren.[206]

The terminal is widely recognized and favorably viewed by the American public. In America's Favorite Architecture, a 2006-07 public survey by the American Institute of Architects, respondents ranked it their 13th-favorite work of architecture in the country, and their fourth-favorite in the city and state after the Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and St. Patrick's Cathedral.[207] In 2013, historian David Cannadine described it as one of the most majestic buildings of the twentieth century.[208] The terminal is also recognized by the American Society of Civil Engineers as a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, added in 2013.[209]

As proposed in 1904, Grand Central Terminal was bounded by Vanderbilt Avenue to the west, Lexington Avenue to the east, 42nd Street to the south, and 45th Street to the north. It included a post office on its east side.[29] The east side of the station house proper is an alley called Depew Place, which was built along with the Grand Central Depot annex in the 1880s and mostly decommissioned in the 1900s when the new terminal was built.[210][211]

The station house measures 800 feet (240 m) along Vanderbilt Avenue (120 feet longer than originally planned), 300 feet (91 m) on 42nd Street, and 105 feet (32 m) tall.[212][29]

Structure and materials

The station and its rail yard have steel frames. The building also uses large steel columns designed to hold the weight of a 20-story office building, which was to be built when additional room was required.[213][214]

The facade and structure of the terminal building primarily use granite. Because granite emits radiation,[215] people who work full-time in the station receive an average dose of 525 mrem/year, more than permitted in nuclear power facilities.[216][217] The base of the exterior is Stony Creek granite, while the upper portion is of Indiana limestone, from Bedford, Indiana.[218]

The interiors use several varieties of stone, including imitation Caen stone for the Main Concourse; cream-colored Botticino marble for the interior decorations; and pink Tennessee marble for the floors of the Main Concourse, Biltmore Room,[82] and Vanderbilt Hall,[105] as well as the two staircases in the Main Concourse.[219][78][41] Real Caen stone was judged too expensive, so the builders mixed plaster, sand, lime, and Portland cement.[41] Most of the remaining masonry is made from concrete.[218] Guastavino tiling, a fireproof tile-and-cement vault pattern patented by Rafael Guastavino, is used in various spaces.[31][122]

Facade

In designing the facade of Grand Central, the architects wanted to make the building seem like a gateway to the city.[220] The south facade, facing 42nd Street, is the front side of the terminal building, and contains large arched windows.[221] The central window resembles a triumphal arch.[220][222] There are two pairs of columns on either side of the central window. The columns are of the Corinthian order, and are partially attached to the granite walls behind them, though they are detached from one another.[221] The facade was also designed to complement that of the New York Public Library Main Branch, another Beaux-Arts edifice located on nearby Fifth Avenue.[222]

The facade includes several large works of art. At the top of the south facade is a 13-foot-wide (4.0 m) clock, which contains the world's largest example of Tiffany glass.[223] The clock is surrounded by the Glory of Commerce sculptural group, a 48-foot-wide (15 m) sculpture by Jules-Félix Coutan, which includes representations of Minerva, Hercules, and Mercury.[206][224] At its unveiling in 1914, the work was considered the largest sculptural group in the world.[224][225][226] Below these works, facing the Park Avenue Viaduct, is an 1869 statue of Cornelius Vanderbilt, longtime owner of New York Central. Sculpted by Ernst Plassmann,[227] the 8.5-foot (2.6 m) bronze is the last remnant[228] of a 150-foot bronze relief installed at the Hudson River Railroad depot at St. John's Park;[229] it was moved to Grand Central Terminal in 1929.[230]

Interior

Main Concourse

.jpg)

The Main Concourse, on the terminal's upper platform level, is located in the geographical center of the station building. The cavernous concourse measures 275 ft (84 m) long by 120 ft (37 m) wide (about 35,000 square feet (3,300 m2) total[33]) by 125 ft (38 m) high.[231][68][232]:74 Its vastness was meant to evoke the terminal's "grand" status.[30]

The concourse is lit by ten globe-shaped chandeliers in the Beaux-Arts style, each of which weighs 800 pounds (360 kg)[98] and contains 110 bulbs.[233] Natural light comes from large windows in its east and west walls.[41] Each wall has three round-arched windows, about 60 feet (18 m) high,[78] identical in size and shape to the three on the terminal's south facade.[234] Catwalks, used mostly for maintenance, run across the east and west windows.[235][43] Their floors are made of semi-transparent rock crystal, cut two inches (51 mm) thick.[236]

The Main Concourse is surrounded on most of its sides by balconies which may be reached by the concourse's West Stairs, original to the station, or the matching East Stairs, added during a 1990s renovation.[78][219] The staircases were modeled after those of the Palais Garnier in Paris, along with the concourse's set of arched windows.[236] Underneath the east and west balconies lie two intricately carved marble water fountains. The fountains, which date to the terminal's opening, still operate and are cleaned daily, though they are rarely used.[36]

Main Concourse ceiling

The Main Concourse's ceiling is an elliptical barrel vault, with its base at an elevation of 121.5 feet and its crown at 160.25 feet. A skylight was originally supposed to be installed to provide light into the terminal, and accommodations were made for a large ceiling light, in case an office building were to be constructed over the terminal.[237]

A false ceiling of square boards, installed in 1944, bears an elaborate mural of constellations painted with more than 2,500 stars and several bands in gold set against a turquoise backdrop.[237][78][238][239][240] It is a less-detailed version of an earlier mural painted directly on the ceiling itself. The original mural, conceived in 1912 by architect Warren and painter Paul César Helleu and executed in 1913 by Brooklyn's Hewlett-Basing Studio,[241][242] became water-damaged and faded by the 1920s. In 1945, New York Central covered it with cement-and-asbestos boards and a new version of the mural. Both the original mural and its mid-century copy contain several astronomical inaccuracies: the stars within some constellations appear correctly as they would from earth, other constellations are reversed left-to-right, as is the overall arrangement of the constellations on the ceiling. Though the astronomical inconsistencies were noticed promptly by a commuter in 1913,[243] they have not been corrected in any of the subsequent renovations of the ceiling.[244][78]

There are half-moon clerestory windows on the north and south sides, with carvings by Salières, alternately depicting a globe adorned with Mercury's staff and a winged wheel that symbolizes the speed of the railway, adorned with lightning bolts to symbolize the line's then-recent electrification. Both designs include laurel and oak branches.[245]

Iconography

Many parts of the terminal are adorned with sculpted oak leaves and acorns, nuts of the oak tree. Cornelius Vanderbilt chose the acorn as the symbol of the Vanderbilt family, and adopted the saying "Great oaks from little acorns grow" as the family motto.[105][231] Among these decorations is a brass acorn finial atop the four-sided clock in the center of the Main Concourse.[115][38] Other acorn or oak leaf decorations include carved wreaths under the Main Concourse's west stairs; sculptures above the lunettes in the Main Concourse; metalwork above the elevators; reliefs above the train gates; and the electric chandeliers in the Main Waiting Room and Main Concourse.[246] These decorations were designed by Salières.[246]

The overlapping letters "G", "C", and "T" are sculpted into multiple places in the terminal, including in friezes atop several windows above the terminal's ticket office. The symbol was designed with the "T" resembling an upside-down anchor, intended as a reference to Cornelius Vanderbilt's commercial beginnings in shipping and ferry businesses.[247] In 2017, the MTA based its new logo for the terminal on the engraved design; MTA officials said its black and gold colors have long been associated with the terminal. The spur of the letter "G" has a depiction of a railroad spike.[248] The 2017 logo succeeded one created by the firm Pentagram for the terminal's centennial in 2013. It depicted the Main Concourse's ball clock set to 7:13, or 19:13 using a 24-hour clock, referencing the terminal's completion in 1913. Both logos omit the word "terminal" in its name, in recognition to how most people refer to the building.[249]

Influence

Among the buildings modeled on Grand Central's design is the Poughkeepsie station, a Metro-North and Amtrak station in Poughkeepsie, New York. It was also designed by Warren and Wetmore and opened in 1918.[250][251] Additionally, Union Station in Utica, New York was partially designed after Grand Central.[252]

Related structures

Park Avenue Viaduct

The Park Avenue Viaduct is an elevated road that carries Park Avenue around the terminal building and the MetLife Building and through the Helmsley Building — three buildings that lie across the line of the avenue. The viaduct rises from street level on 40th Street south of Grand Central, splits into eastern (northbound) and western (southbound) legs above the terminal building's main entrance,[234] and continues north around the station building, directly above portions of its main level. The legs of the viaduct pass around the MetLife Building, into the Helmsley Building, and re-emerge at street level on 46th Street.

The viaduct was built to facilitate traffic along 42nd Street[253] and along Park Avenue, which at the time was New York City's only discontinuous major north–south avenue.[254] When the western leg of the viaduct was completed in 1919,[255] it served both directions of traffic, and also served as a second level for picking up and dropping off passengers. After an eastern leg for northbound traffic was added in 1928, the western leg was used for southbound traffic only.[253] A sidewalk, accessible from the Grand Hyatt hotel, runs along the section of the viaduct that is parallel to 42nd Street.[256]

Post office and baggage building

Grand Central Terminal has a post office at 450 Lexington Avenue, built from 1906 to 1909.[10][28] The architecture of the original post office building matches that of the terminal, as the structures were designed by the same architects.[257] The post office building expanded into a second building, directly north of the original structure, in 1915.[257][258] From the beginning, Grand Central's post office was designed to handle massive volumes of mail, though it was not as large as the James A. Farley Building, the post office that was built with the original Penn Station.[259]

The terminal complex originally included a six-story building for baggage handling just north of the main station building. Departing passengers unloaded their luggage from taxis or personal vehicles on the Park Avenue Viaduct, and elevators brought it to the baggage passageways (now part of Grand Central North), where trucks brought the luggage to the respective platforms. The process was reversed for arriving passengers.[28][130] Biltmore Hotel guests arriving at Grand Central could get baggage delivered to their rooms.[28] The baggage building was later converted to an office building. The structure was demolished in 1961[260][261] to make way for the MetLife Building.[28]

Subway station

The terminal's subway station, Grand Central–42nd Street, serves three lines: the IRT Lexington Avenue Line (serving the 4, 5, 6, and <6> trains), the IRT Flushing Line (serving the 7 and <7> trains), and the IRT 42nd Street Shuttle to Times Square.[11] Originally built by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT),[262][263] the lines are operated by the MTA as part of the New York City Subway.[264][265]

The Main Concourse is connected to the subway platforms' mezzanine via the Shuttle Passage.[34][264] The platforms can also be reached from the 42nd Street Passage via stairs, escalators, and an elevator to the fare control area for the Lexington Avenue and Flushing Lines.[265]

The 42nd Street Shuttle platforms, located just below ground level, opened in 1904 as an express stop on the original IRT subway.[262] The Lexington Avenue Line's platforms, which were opened in 1918 when the original IRT subway platforms were converted to shuttle use,[266] run underneath the southeastern corner of the station building at a 45-degree angle, to the east of and at a lower level than the shuttle platforms.[267] The Flushing Line platform opened in 1915;[268] it is deeper than the Lexington Avenue Line's platforms because it is part of the Steinway Tunnel, a former streetcar tunnel that descends under the East River to the east of Grand Central.[268][263] There was also a fourth line connected to Grand Central Terminal: a spur of the IRT Third Avenue elevated,[263] which stopped at Grand Central starting in 1878;[269] it was made obsolete by the subway's opening, and closed in 1923.[270]

During the terminal's construction, there were proposals to allow commuter trains to pass through Grand Central and continue into the subway tracks. However, these plans were deemed impractical because commuter trains would have been too large to fit within the subway tunnels.[263]

History

Three buildings serving essentially the same function have stood on the current Grand Central Terminal's site.[271]

Predecessors

.jpg)

Grand Central Terminal arose from a need to build a central station for the Hudson River Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York and New Haven Railroad in modern-day Midtown Manhattan.[271][272][273] The Harlem Railroad originally ran as a steam railroad on street level along Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue),[274][275][276][277] while the New Haven Railroad ran along the Harlem's tracks in Manhattan per a trackage agreement.[274][275][276] The business magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the Hudson River and New York Central Railroads in 1867, and merged them two years later.[278][276][277] Vanderbilt developed a proposal to unite the three separate railroads at a single central station, replacing the separate and adjacent stations that created chaos in baggage transfer.[271]

Vanderbilt commissioned John B. Snook to design his new station, dubbed Grand Central Depot, on the site of the 42nd Street depot.[279][280] Snook's final design was in the Second Empire style.[275][281] Construction started on September 1, 1869, and the depot was completed by October 1871.[275] Due to frequent accidents between pedestrians and trains running on street level, Vanderbilt proposed the Fourth Avenue Improvement Project in 1872.[275] The improvements were completed in 1874, allowing trains approaching Grand Central Depot from the north to descend into the Park Avenue Tunnel at 96th Street and continue underground into the new depot.[275] Traffic at Grand Central Depot grew quickly, filling its 12 tracks to capacity by the mid-1890s, not the late 1890s or early 1900s as expected.[282] In 1885, a seven-track annex with five platforms was added to the east side of the existing terminal.[166][282][283]

Grand Central Depot had reached its capacity again by the late 1890s,[284] and it carried 11.5 million passengers a year by 1897.[285] As a result, the railroads renovated the head house extensively based on plans by railroad architect Bradford Gilbert.[286][284] The reconstructed building was renamed Grand Central Station.[231][68] The new waiting room opened in October 1900.[8]

As train traffic increased in the late 1890s and early 1900s, so did the problems of smoke and soot produced by steam locomotives in the Park Avenue Tunnel, the only approach to the station.[281][287][166][288] This contributed to a crash on January 8, 1902, when a southbound train overran signals in the smoky Park Avenue Tunnel and collided with another southbound train,[289][290][288] killing 15 people and injuring more than 30 others.[291][292][293] Shortly afterward, the New York state legislature passed a law to ban all steam trains in Manhattan by 1908.[287][290][294][295] William J. Wilgus, the New York Central's vice president, later wrote a letter to New York Central president William H. Newman. Wilgus proposed to electrify and place the tracks to Grand Central in tunnels, as well as constructing a new railway terminal with two levels of tracks and making other infrastructure improvements.[231][294] In March 1903, Wilgus presented a more detailed proposal to the New York Central board.[166][289][296][288] The railroad's board of directors approved the $35 million project in June 1903; ultimately, almost all of Wilgus's proposal would be implemented.[289][296]

Replacement

The entire building was to be torn down in phases and replaced by the current Grand Central Terminal. It was to be the biggest terminal in the world, both in the size of the building and in the number of tracks.[231][68] The Grand Central Terminal project was divided into eight phases, though the construction of the terminal itself comprised only two of these phases.[N 5]

The current building was intended to compete with the since-demolished Pennsylvania Station, a majestic electric-train hub being built on Manhattan's west side for arch-rival Pennsylvania Railroad by McKim, Mead & White.[298] In 1903, New York Central invited four architecture firms to a design competition to decide who would design the new terminal.[299] Reed and Stem were ultimately selected,[202] as were Warren and Wetmore, who were not part of the original competition.[300][301][202][302][295] Reed and Stem were responsible for the overall design of the station, while Warren and Wetmore worked on designing the station's Beaux-Arts exterior.[302][303][295] However, the team had a tense relationship due to constant design disputes.[301]

Construction on Grand Central Terminal started on June 19, 1903.[300] Wilgus proposed to demolish, excavate, and build the terminal in three sections or "bites",[304] to prevent railroad service from being interrupted during construction.[305] About 3,200,000 cubic yards (2,400,000 m3) of the ground were excavated at depths of up to 10 floors, with 1,000 cubic yards (760 m3) of debris being removed from the site daily. Over 10,000 workers were assigned to the project.[306][190][307] The total cost of improvements, including electrification and the development of Park Avenue, was estimated at $180 million in 1910.[212] Electric trains on the Hudson Line started running to Grand Central on September 30, 1906,[308] and the segments of all three lines running into Grand Central had been electrified by 1907.[307]

After the last train left Grand Central Station at midnight on June 5, 1910, workers promptly began demolishing the old station.[9] The last remaining tracks from the former Grand Central Station were decommissioned on June 21, 1912.[304] The new terminal was opened on February 2, 1913.[309][310][311]

Heyday

The terminal spurred development in the surrounding area, particularly in Terminal City, a commercial and office district created above where the tracks were covered.[312][313][314][315] The development of Terminal City also included the construction of the Park Avenue Viaduct, surrounding the station, in the 1920s.[316][317][318] The new electric service led to increased development in New York City's suburbs, and passenger traffic on the commuter lines into Grand Central more than doubled in the seven years following the terminal's completion.[319] Passenger traffic grew so rapidly that by 1918, New York Central proposed expanding Grand Central Terminal.[320]

In 1923, the Grand Central Art Galleries opened in the terminal. A year after it opened, the galleries established the Grand Central School of Art, which occupied 7,000 square feet (650 m2) on the seventh floor of the east wing of the terminal.[321][322] The Grand Central School of Art remained in the east wing until 1944,[323] and it moved to the Biltmore Hotel in 1958.[324][325]

Decline

In 1947, over 65 million people traveled through Grand Central, an all-time high.[190] The station's decline came soon afterward with the beginning of the Jet Age and the construction of the Interstate Highway System. There were multiple proposals to alter the terminal, including several replacing the station building with a skyscraper; none of the plans were carried out.[326] Though the main building site was not redeveloped, the Pan Am Building (now the MetLife Building) was erected just to the north, opening in 1963.[327]

In 1968, New York Central, facing bankruptcy, merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad to form the Penn Central Railroad. The new corporation proposed to demolish Grand Central Terminal and replace it with a skyscraper, as the Pennsylvania Railroad had done with the original Penn Station in 1963.[328] However, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, which had designated Grand Central a city landmark in 1967, refused to consider the plans.[329][330] The resulting lawsuit went to the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled in favor of the city.[331] After Penn Central went into bankruptcy in 1970, it retained title to Grand Central Terminal.[332] When Penn Central reorganized as American Premier Underwriters (APU) in 1994, it retained ownership of Penn Central. In turn, APU was absorbed by American Financial Group.[333]

Grand Central and the surrounding neighborhood became dilapidated during the 1970s, and the interior of Grand Central was dominated by huge advertisements, which included the Kodak Colorama photos and the Westclox "Big Ben" clock.[66] In 1975, Donald Trump bought the Commodore Hotel to the east of the terminal for $10 million and then worked out a deal with Jay Pritzker to transform it into one of the first Grand Hyatt hotels.[334] Grand Central Terminal was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 and declared a National Historic Landmark in the following year.[335][336][337] This period was marked by a bombing on September 11, 1976, when a group of Croatian nationalists planted a bomb in a coin locker at Grand Central Terminal and hijacked a plane; the bomb was not disarmed properly, and the explosion injured three NYPD officers and killed one bomb squad specialist.[338][339]

The terminal was used for intercity transit until 1991. Amtrak, the national rail system formed in 1971, ran its last train from Grand Central on April 6, 1991, upon the completion of the Empire Connection on Manhattan's West Side. The connection allowed trains using the Empire Corridor from Albany, Toronto, and Montreal to use Penn Station.[340] However, some Amtrak trains used Grand Central during the summers of 2017 and 2018 due to maintenance at Penn Station.[341][342]

Renovation and subsequent expansions

In 1988, the MTA commissioned a study of the Grand Central Terminal, which concluded that parts of the terminal could be turned into a retail area.[343] The agency announced an $113.8 million renovation of the terminal in 1995.[87] During this renovation, all advertisements were removed and the station was restored.[66] The most striking effect was the restoration of the Main Concourse ceiling, revealing the painted skyscape and constellations.[344][345] The renovations included the construction of the East Stairs, a curved monumental staircase on the east side of the station building that matched the West Stairs.[346] An official re-dedication ceremony was held on October 1, 1998, marking the completion of the interior renovations.[347][348]

.jpg)

On February 1, 2013, numerous displays, performances, and events were held to celebrate the terminal's centennial.[349][350] The MTA awarded contracts to replace the display boards and public announcement systems and add security cameras at Grand Central Terminal in December 2017.[60] The MTA also proposed to repair the Grand Central Terminal train shed's concrete and steel as part of the 2020–2024 MTA Capital Program.[351] In February 2019, it was announced that the Grand Hyatt New York hotel that abuts Grand Central Terminal to the east would be torn down and replaced with a larger mixed-use structure over the next several years.[352][353]

.jpg)

The East Side Access project, underway since 2007, is planned to bring Long Island Rail Road trains into the terminal when completed. LIRR trains will reach Grand Central from Harold Interlocking in Sunnyside, Queens, via the existing 63rd Street Tunnel and new tunnels under construction on both the Manhattan and Queens sides. LIRR trains will arrive and depart from a bi-level, eight-track tunnel with four platforms more than 90 feet (27 m) below the Metro-North tracks.[27] The project includes a new 350,000-square-foot retail and dining concourse[354] and new entrances at 45th, 46th, and 48th streets.[355] Cost estimates have jumped from $4.4 billion in 2004, to $6.4 billion in 2006, then to $11.1 billion. The new stations and tunnels are to begin service in December 2022.[26][27]

In December 2006, American Financial sold Grand Central Terminal to Midtown TDR Ventures, LLC, an investment group controlled by Argent Ventures,[356] which renegotiated the lease with the MTA until 2274.[357] In November 2018, the MTA proposed to buy the station and the Hudson and Harlem Lines for up to $35.065 million, using the only purchase window specified in the lease: April 2017 to October 2019.[332][358] The MTA approved the proposal on November 15, 2018,[359][360][361] and the agency took ownership of the terminal and rail lines in March 2020.[362]

Innovations

Passenger improvements

.jpg)

At the time of its completion, Grand Central Terminal offered several innovations in transit-hub design. One was the use of ramps, rather than staircases, to conduct passengers and luggage through the facility. Two ramps connected the lower-level suburban concourse to the main concourse; several more led from the main concourse to entrances on 42nd Street. These ramps allowed all travelers to easily move between Grand Central's two underground levels.[31][363][222] There were also 15 passenger elevators and six freight-and-passenger elevators scattered around the station.[222] The separation of commuter and intercity trains, as well as incoming and outgoing trains, ensured that most passengers on a given ramp would be traveling in the same direction.[364] At its opening in 1913, the terminal was theoretically able to accommodate 100 million passengers a year.[187]