Cuyahoga River

The Cuyahoga River[7] (/ˌkaɪ.əˈhɒɡə/ KY-ə-HOG-ə, or /ˌkaɪ.əˈhoʊɡə/ KY-ə-HOH-gə[8][9][10][11]) is a river in the United States, located in Northeast Ohio, that runs through the city of Cleveland and feeds into Lake Erie. As Cleveland emerged as a major center for manufacturing, the river became heavily affected by industrial pollution, so much so that it "caught fire" at least 13 times, most famously on June 22, 1969, helping to spur the American environmental movement.[12] Since then, the river has been extensively cleaned up through the efforts of Cleveland's city government and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA).[13] In 2019, the American Rivers conservation association named the Cuyahoga "River of the Year" in honor of "50 years of environmental resurgence."[14]

| Cuyahoga River | |

|---|---|

The Cuyahoga River in Cleveland. | |

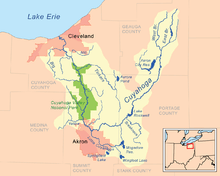

Map of the Cuyahoga River drainage basin | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| Counties | Cuyahoga, Summit, Portage, Geauga[1] |

| Cities | Cuyahoga Falls, Cleveland, Akron, Kent[1] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| ⁃ coordinates | 41°26′26″N 81°09′07″W[2] Confluence of East Branch Cuyahoga River[3] and West Branch Cuyahoga River[4] near Pond Road and Rapids Road, Burton, Geauga County, Ohio |

| ⁃ elevation | 1,093 feet (333.1 m)[3][4] |

| Mouth | |

⁃ location | Lake Erie at Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, Ohio[2] |

⁃ coordinates | 41°30′13″N 81°42′44″W |

⁃ elevation | 571 feet (174.0 m)[2] |

| Length | 84.9 miles (136.6 km)[5] |

| Basin size | 809 square miles (2,100 km2)[6] |

Etymology

The name Cuyahoga is believed to mean "crooked river" from the Mohawk Indian name Cayagaga, although the Senecas called it Cuyohaga, or "place of the jawbone".[15][16]

Course

The Cuyahoga watershed begins its 100-mile (160 km) journey in Hambden, Ohio, flowing southward to the confluence of the East Branch Cuyahoga River and West Branch Cuyahoga River in Burton, where the Cuyahoga River officially begins.[2] It continues on its 84.9 miles (136.6 km) journey flowing southward to Akron and Cuyahoga Falls, where it turns sharply north and flows through the Cuyahoga Valley National Park in northern Summit County and southern Cuyahoga County. It then flows through Independence, Valley View, Cuyahoga Heights, Newburgh Heights and Cleveland to its northern terminus, emptying into Lake Erie. The Cuyahoga River and its tributaries drain 813 square miles (2,110 km2) of land in portions of six counties.

The river is a relatively recent geological formation, formed by the advance and retreat of ice sheets during the last ice age. The final glacial retreat, which occurred 10,000–12,000 years ago, caused changes in the drainage pattern near Akron. This change in pattern caused the originally south-flowing Cuyahoga to flow to the north. As its newly reversed currents flowed toward Lake Erie, the river carved its way around glacial debris left by the receding ice sheet, resulting in the river's winding U-shape. These meanderings stretched the length of the river (which was only 30 miles (50 km) when traveled directly) into a 100-mile (160 km) trek from its headwaters to its mouth. The depth of the river (except where noted below) ranges from 3 to 6 ft (1 to 2 m).

History

The river was one of the features along which the "Greenville Treaty Line" ran beginning in 1795, per the Treaty of Greenville that ended the Northwest Indian War in the Ohio Country, effectively becoming the western boundary of the United States and remaining so briefly. On July 22, 1796, Moses Cleaveland, a surveyor charged with exploring the Connecticut Western Reserve, arrived at the mouth of the Cuyahoga and subsequently located a settlement there, which became the city of Cleveland.

Environmental cleanup

.jpg)

The Cuyahoga River, at times during the 20th century, was one of the most polluted rivers in the United States. The reach from Akron to Cleveland was devoid of fish. A 1968 Kent State University symposium described one section of the river:

From 1,000 feet [300 m] below Lower Harvard Bridge to Newburgh and South Shore Railroad Bridge, the channel becomes wider and deeper and the level is controlled by Lake Erie. Downstream of the railroad bridge to the harbor, the depth is held constant by dredging, and the width is maintained by piling along both banks. The surface is covered with the brown oily film observed upstream as far as the Southerly Plant effluent. In addition, large quantities of black heavy oil floating in slicks, sometimes several inches thick, are observed frequently. Debris and trash are commonly caught up in these slicks forming an unsightly floating mess. Anaerobic action is common as the dissolved oxygen is seldom above a fraction of a part per million. The discharge of cooling water increases the temperature by 10 to 15 °F [5.6 to 8.3 °C]. The velocity is negligible, and sludge accumulates on the bottom. Animal life does not exist. Only the algae Oscillatoria grows along the piers above the water line. The color changes from gray-brown to rusty brown as the river proceeds downstream. Transparency is less than 0.5 feet [0.15 m] in this reach. This entire reach is grossly polluted.[17]

At least 13 fires have been reported on the Cuyahoga River, the first occurring in 1868.[12][18] The largest river fire, in 1952, caused over $1 million in damage[12] to boats, a bridge, and a riverfront office building.[19]

Things began to change in the late 1960s, when new mayor Carl Stokes and his utilities director rallied voters to approve a $100-million bond to rehabilitate Cleveland's rivers.[20] Then the mayor seized the opportunity of a June 22, 1969 river fire triggered by a spark from a passing rail car igniting an oil slick to bring reporters to the river to raise attention to the issue.[20] The 1969 fire caused approximately $50,000 in damage, mostly to an adjacent railroad bridge,[18] but despite mayor Stokes' efforts, very little attention was initially given to the incident, and it was not considered a major news story in the Cleveland media.[18]

However, the incident did soon garner the attention of Time magazine, which used a dramatic photo of the even larger 1952 blaze[20] in an article on the pollution of America's waterways. The article described the Cuyahoga as the river that "oozes rather than flows" and in which a person "does not drown but decays"[21] and listed other badly-polluted rivers across the nation.[20] (No pictures of the 1969 fire are known to exist, as local media did not arrive on the scene until after the fire was under control[18]). The article launched Time's new "Environment" section, and gained wide readership not only on its own merit, but because the same issue featured coverage of astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landing on the moon the previous week in the Apollo 11 mission, and had Senator Ted Kennedy on the cover for a story on the Chappaquiddick incident in which Kennedy's automobile passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, had drowned.[20]

The 1969 Cuyahoga River fire helped spur an avalanche of water pollution control activities, resulting in the Clean Water Act, Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, and the creation of the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA). Mayor Stokes gave Congressional testimony on his and other major big cities' struggles with polluting industries to restore the environmental health of their communities.[20] As a result, large point sources of pollution on the Cuyahoga have received significant attention from the OEPA in subsequent decades. These events are referred to in Randy Newman's 1972 song "Burn On," R.E.M.'s 1986 song "Cuyahoga," and Adam Again's 1992 song "River on Fire." Great Lakes Brewing Company of Cleveland named its Burning River Pale Ale after the event.

In December 1970 a federal grand jury investigation led by U.S. Attorney Robert Jones began, of water pollution allegedly being caused by about 12 companies in northeastern Ohio; it was the first grand jury investigation of water pollution in the area.[22] The Attorney General of the United States, John N. Mitchell, gave a Press Conference December 18, 1970 referencing new pollution control litigation, with particular reference to work with the new Environmental Protection Agency, and announcing the filing of a law suit that morning against the Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation for discharging substantial quantities of cyanide into the Cuyahoga River near Cleveland.[23] Jones filed the misdemeanor charges in District Court, alleging violations of the 1899 Rivers and Harbors Act.[24] There were multiple other suits filed by Jones.[25][26][27]

.jpg)

Water quality has improved and, partially in recognition of this improvement, the Cuyahoga was designated one of 14 American Heritage Rivers in 1998.[28] Despite these efforts, pollution continues to exist in the Cuyahoga River due to other sources of pollution, including urban runoff, nonpoint source problems, combined sewer overflows,[29] and stagnation due to water impounded by dams. For this reason, the Environmental Protection Agency classified portions of the Cuyahoga River watershed as one of 43 Great Lakes Areas of Concern. The most polluted portions of the river now generally meet established aquatic life water quality standards except near dam impoundments. The reasons for not meeting standards near the dam pools are habitat and fish passage issues rather than water quality. River reaches that were once devoid of fish now support 44 species. The most recent survey in 2008 revealed the two most common species in the river were hogsuckers and spotfin shiners, both moderately sensitive to water quality. Habitat issues within the 5.6-mile (9.0 km) navigation channel still preclude a robust fishery in that reach. Recreation water quality standards (using bacteria as indicators) are generally met during dry weather conditions, but are often exceeded during significant rains due to nonpoint sources and combined sewer overflows. In March 2019 the OEPA declared fish caught in the river safe to eat.[30]

Modifications

The lower Cuyahoga River has been subjected to numerous changes. Originally, the Cuyahoga river met Lake Erie approximately 4,000 feet (1.2 km) west of its current mouth, forming a shallow marsh. The current mouth is man-made, and it lies just west of present-day downtown Cleveland, which allows shipping traffic to flow freely between the river and the lake. Additionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers periodically dredges the navigation channel of the otherwise shallow river to a depth of 27 feet (8.2 m), along the river's lower 5 miles (8.0 km), from its mouth up to the Mittal Steel Cleveland Works steel mills, to accommodate Great Lakes freighter traffic which serves the bulk (asphalt, gravel, petroleum, salt, steel, and other) industries located along the lower Cuyahoga River banks in Cleveland's Flats district. The Corps of Engineers has also straightened river banks and widened turning basins in the Federal Navigation Channel on the lower Cuyahoga River to facilitate maritime operations.

Ice-breaking

The United States Coast Guard sometimes conducts fall and spring ice-breaking operations along Lake Erie and the lower Cuyahoga River to prolong the Great Lakes shipping season, depending on shipping schedules and weather conditions.

Flooding

Some attempts (including dams and dredging) have been made to control flooding along the Cuyahoga River basin. As a result of speculative land development, buildings have been erected on many flat areas that are only a few feet above normal river levels. Sudden strong rain or snow storms can create severe flooding in these low-lying areas.

The upper Cuyahoga River, starting at 1,093 feet (333 m) over 84 miles (135 km) from its mouth, drops in elevation fairly steeply, creating falls and rapids in some places; the lower Cuyahoga River only drops several feet along the last several miles of the lower river to 571 feet (174 m)[2] at the mouth on Lake Erie, resulting in relatively slow-moving waters that can take a while to drain compared to the upper Cuyahoga.

Some tributary elevations above are higher than the Cuyahoga River elevation, because of small waterfalls at or near their confluences; and distances are measured in "river miles" along the river's length from its mouth on Lake Erie.

Dams

Ohio and Erie Canal diversion dam

The Brecksville Dam[lower-alpha 1] at river mile 20 is the first dam upstream of Lake Erie. It affects fish populations by restricting their passage.[31] The EPA is currently attempting to shut down and remove the dam.[32] Removal is planned for 2018 or 2019.[33]

Gorge Metropolitan Park Dam

The largest dam is the Gorge Metropolitan Park Dam, also known as the FirstEnergy Dam, on the border between Cuyahoga Falls and Akron. This 57-foot dam has for over 90 years submerged the falls for which the City of Cuyahoga Falls was named; more to the point of water quality, it has created a large stagnant pool with low dissolved oxygen.[34]

The FirstEnergy Dam was built by the Northern Ohio Traction and Light Co. in 1912 to serve the dual functions of generating hydropower for its local streetcar system and providing cooling-water storage for a coal-burning power plant; however, the hydropower operation was discontinued in 1958, and the coal-burning plant was decommissioned in 1991.[35] Some environmental groups and recreational groups want the dam removed.[36] Others contend such an effort would be expensive and complicated, for at least two reasons: first, the formerly hollow dam was filled in with concrete in the early 1990s, and second, because of the industrial history of Cuyahoga Falls, the sediment upstream of the dam is expected to contain hazardous chemicals, possibly including heavy metals and PCBs. The Ohio EPA estimated removal of the dam would cost $5–10 million, and removal of the contaminated sediments $60 million.[37] The dam is licensed through 2041.

Advanced Hydro Solutions (AHS), a company based in Fairlawn, Ohio, filed a notice of intent to use the dam to generate hydropower. The company contends hydropower is a cleaner source of power and the emissions saved by the plant will be the equivalent of taking 10,000 cars off the road.[37] Citing concerns with erosion, dewatering of the scenic river reach below the dam, and use that is inconsistent with the Gorge MetroPark's purpose, opponents to this plan include, in addition to environmental and recreational groups, some governmental agencies, including Summit Metro Parks, the U.S. Department of the Interior, and the Ohio EPA. At public meetings held on July 27, 2005, the proposed project, which would generate enough electricity to power 2000 homes, encountered substantial opposition. On May 25, 2007, AHS suffered a setback in its effort to develop the site. The United States Court of Appeals for the sixth circuit denied its application to conduct tests at the site, refusing to overturn a lower court's ruling that the MetroParks had the right to deny AHS access to conduct the tests.[38] In a letter dated June 14, 2007, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) terminated AHS's application for the Integrated Licensing Permit without prejudice, citing the company's failure to adhere to strict timelines. FERC will allow AHS to refile if it can conduct the required studies and move forward with the project.[39][40] The final decision from the FERC on the project was due in July 2009.[37] On June 12, 2009, AHS dropped its permit and terminated the project.[41]

On April 9, 2019, officials from the U.S. EPA and Ohio EPA announced a plan to remove the Gorge Metropolitan Park Dam by 2023 at a cost of $65 to $70 million. Funding for the project was authorized through the Great Lakes Legacy Act with funds coming from the City of Akron and members of the Gorge Dam Stakeholder Committee, including Summit Metro Parks, FirstEnergy, and the City of Cuyahoga Falls.[42]

Dams in Cuyahoga Falls

Two dams in Cuyahoga Falls, the Sheraton and LeFever Dams, were scheduled for demolition in late 2012.[43] This is the result of an agreement between the City of Cuyahoga Falls, which owns the dams, and the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, which will provide $1 million of funding to remove the dams. This schedule was delayed, in part because of complications with the bidding process, and because of requirements from the Army Corps of Engineers. On December 12, 2012, the ACOE issued a permit, allowing the demolition to proceed.[44] As part of the project, a water trail will be developed.[45] In early June 2013, dam removal began, and ended in July 2013.[46] This will bring about a mile of the river back to its natural state, remove 35 feet of structures, and expose an equivalent quantity of whitewater for recreation. As of August 20, 2013, both small dams had effectively been totally removed, and there is essentially no impoundment of water now. Cleanup and remediation of the general area within downtown Cuyahoga Falls remains to be completed. In 2019, attempts by the city to address increased erosion as a result of the removal of these and other area dams were publicized.[47]

Munroe Falls Dam

Two other dams, in Kent and in Munroe Falls, though smaller, have had an even greater impact on water quality due to the lower gradient in their respective reaches. For this reason, the Ohio EPA required the communities to mitigate the effects of the dams.

The Munroe Falls Dam was modified in 2005.[48] Work on this project uncovered a natural waterfall.[49] Given this new knowledge about the riverbed, some interested parties, including Summit County, campaigned for complete removal of the dam. The revised plan, initially denied on September 20, 2005, was approved by the Munroe Falls City Council on a week later. The 11.5 foot sandstone dam has since been removed, and in its place now is a natural ledge with a 4.5 foot drop at its greatest point.[50][51]

Kent Dam

The Kent Dam was bypassed in 2004.[52]

Lists

Variant names

According to the United States Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System, the Cuyahoga River has also been known as:[2]

- Cajahage River

- Cayagaga River

- Cayahoga River

- Cayhahoga River

- Cayohoga River

- Cujahaga River

- Cuyohaga River

- Gichawaga Creek

- Goyahague River

- Gwahago River

- River de Saguin

- Rivière Blanche

- Rivière à Seguin

- Saguin River

- Yashahia

- Cayahaga River

- Cayanhoga River

- Cayhoga River

- Coyahoga River

- Cuahoga River

- Guyahoga River

- Gwahoga River

- Kiahagoh River

- White River[53]

Dams

| RM [lower-alpha 2][54] |

Coordinates | Elevation | Locality | County | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20.71 [55] |

41°19′15″N 81°35′15″W[56] | Ohio and Erie Canal diversion dam, built 1825–1827 upstream from downstream from Station Road-Bridle Trail bridge | |||

| 45.8 [55] |

41°07′23″N 81°29′50″W[57] | 840 feet (260 m)[57] | Summit | Gorge Metropolitan Park Dam, built in 1912, upstream from downstream from | |

| 49.9 [55][58] |

41°08′14″N 81°28′53″W[59] | 1,007 feet (307 m)[59] | Cuyahoga Falls | Summit | Cuyahoga Falls Low Head Dam, upstream from Portage Trail bridge, downstream from |

| 54.8 [58] |

41°9′12″N 81°21′35″W[60] | Kent | Portage | Kent dam, upstream from immediately downstream from West Main Street bridge | |

| 57.97 [5] |

41°10′58″N 81°19′51″W[61] | 1,063 feet (324 m)[61] | Franklin Township | Portage | Lake Rockwell Dam, upstream from Ravenna Road bridge, downstream from |

Tributaries

Generally, rivers are larger than creeks, which are larger than brooks, which are larger than runs. Runs may be dry except during or after a rain, at which point they can flash flood and be torrential.

Default is standard order from mouth to upstream:[lower-alpha 3]

| RM [lower-alpha 2][54] |

Coordinates | Elevation | Tributary | Municipality | County | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41°29′32″N 81°42′53″W[62] | 577 feet (176 m)[62] | Old River (Cuyahoga River) | Cleveland | Cuyahoga | near Division Avenue/River Road | |

| 4.46 [55] | 41°28′52″N 81°40′36″W[63] | 581 feet (177 m)[63] | Kingsbury Run (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga | near Independence Road and Rockefeller Avenue | |

| 5.05 [55] | 41°28′10″N 81°40′10″W[64] | 581 feet (177 m)[64] | Morgan Run (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga | near Independence Road and Pershing Avenue | |

| 5.29–5.4 [55] | 41°27′50″N 81°40′45″W[65] | 577 feet (176 m)[65] | Burk Branch (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga | near CW steel mill | |

| 7.2 [55] | 41°26′45″N 81°41′9″W[66] | 577 feet (176 m)[66] | Big Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga | near Jennings Road, Harvard Avenue and Valley Road | |

| 10.84–11.4 [55] | 41°25′00″N 81°38′47″W[67] | 591 feet (180 m)[67] | West Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga | near SR-17 Granger Road, Valley Belt Road, and I-77 | |

| 11.4 [55] | 41°24′57″N 81°38′22″W[68] | 587 feet (179 m)[68] | Mill Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga | near Canal Road and Warner Road | |

| 16.36 [55] | 41°21′54″N 81°36′35″W[69] | 610 feet (190 m)[69] | Tinkers Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga, Summit and Portage | near Canal Road and Tinkers Creek Road | |

| 18.08 | 0 feet (0 m) | from Willow Lake | ||||

| 20.88 [55] | 41°19′7″N 81°35′13″W[70] | 627 feet (191 m)[70] | Chippewa Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Cuyahoga and Summit | near Chippewa Creek Drive and Riverview Road | |

| 24.16 [55] | 41°17′10″N 81°33′50″W[71] | 636 feet (194 m)[71] | Brandywine Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | near Highland Road | |

| 25.72 [55] | 41°16′25″N 81°33′51″W[72] | 646 feet (197 m)[72] | Stanford Run | Summit | near Stanford Road | |

| 41°15′42″N 81°33′29″W[73] | 650 feet (200 m)[73] | Grannys Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | near Boston Mills Road and Riverview Road | ||

| 28.79 [55] | 41°14′35″N 81°33′13″W[74] | 689 feet (210 m)[74] | Slipper Run | Summit | near SR-303 Main Street/West Streetsboro Road and Riverview Road | |

| 28.98 [55] | 41°14′34″N 81°32′59″W[75] | 676 feet (206 m)[75] | Boston Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | near East Mill Street and West Mill Street | |

| 29.24 [55] | Peninsula Creek | Summit | ||||

| 29.82 [55] | 41°13′58″N 81°32′57″W[76] | 689 feet (210 m)[76] | Haskell Run | Summit | near Akron-Peninsula Road | |

| 30.26 [55] | 41°13′42″N 81°32′59″W[77] | 692 feet (211 m)[77] | Salt Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | near Akron-Peninsula Road and Truxell Road | |

| 30.66 [55] | 41°13′34″N 81°33′6″W[78] | 699 feet (213 m)[78] | Dickerson Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | near | |

| 31.47 [55] | 41°13′3″N 81°33′35″W[79] | 699 feet (213 m)[79] | Langes Run | Summit | ||

| 32.3 [55] | 41°12′30″N 81°33′46″W[80] | 709 feet (216 m)[80] | Robinson Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | ||

| 33.08 [55][81] | 41°12′10″N 81°34′11″W[82] | 709 feet (216 m)[82] | Furnace Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit and Cuyahoga | ||

| 37.16 [55] | 41°9′47″N 81°34′25″W[83] | 728 feet (222 m)[83] | Yellow Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Summit and Medina | ||

| 37.26 [55] | 41°9′42″N 81°34′25″W[84] | 728 feet (222 m)[84] | Woodward Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | ||

| 39.12 [55] | 41°8′24″N 81°33′37″W[85] | 738 feet (225 m)[85] | Sand Run (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | ||

| 39.78 [55] | 41°8′17″N 81°33′5″W[86] | 738 feet (225 m)[86] | Mud Brook (Cuyahoga River) | Summit | ||

| 42.27 [55] | 41°7′9″N 81°31′45″W[87] | 758 feet (231 m)[87] | Little Cuyahoga River | Summit | ||

| 52.1 [58] | 41°8′26″N 81°23′56″W[88] | 1,004 feet (306 m)[88] | Fish Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Stow | Summit and Portage | near North River Road between Marsh Road and Verner Road |

| 53.7 [58] | 41°8′32″N 81°22′24″W[89] | 1,010 feet (310 m)[89] | Plum Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Kent | Portage | near Cherry Street and Mogadore Road |

| 56.8 [58] | 41°10′13″N 81°20′17″W[90] | 1,027 feet (313 m)[90] | Breakneck Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Kent/Franklin Township border | Portage | near River Bend Boulevard and Beechwold Drive |

| 57.6[58]-57.97 [5] | Twin Lakes Outlet | |||||

| 59.95 [5] | 41°11′19″N 81°16′40″W[91] | 1,070 feet (330 m)[91] | Eckert Ditch (Cuyahoga River) | Portage | ||

| 63.45 [5] | 41°14′9″N 81°18′46″W[92] | 1,109 feet (338 m)[92] | Yoder Ditch | Portage | ||

| 65.19 [5] | Bollingbrook, Portage | |||||

| 66.33 [5] | 41°14′31″N 81°15′36″W[93] | 1,096 feet (334 m)[93] | Harper Ditch (Cuyahoga River) | Portage | ||

| 76.64 [5] | 41°16′55″N 81°8′31″W[94] | 1,010 feet (310 m)[94] | Black Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Portage | near SR-700 Welshfield Limaville Road between SR-254 Pioneer Trail and CR-224 Hankee Road | |

| 79.15 [5] | 41°22′35″N 81°9′4″W[95] | 1,093 feet (333 m)[95] | Sawyer Brook (Cuyahoga River) | Geauga | near Main Market Road US-422 and Claridon Troy Road | |

| 83.29 [5] | 41°22′30″N 81°12′13″W[96] | 1,122 feet (342 m)[96] | Bridge Creek (Cuyahoga River) | Geauga | ||

| 84.9 [5] | 41°26′25″N 81°9′6″W[4] | 1,093 feet (333 m)[4] | West Branch Cuyahoga River | Geauga | ||

| 84.9 [5] | 41°26′25″N 81°9′5″W[3] | 1,093 feet (333 m)[3] | East Branch Cuyahoga River | Geauga |

See also

- List of crossings of the Cuyahoga River

- List of rivers of Ohio

Notes

- The Ohio and Erie Canal diversion dam is located under the Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge over the Cuyahoga River valley.

- RM stands for "river mile" and refers to the method used by federal and state government agencies to identify locations along a water body. Mileage is defined as the lineal distance from the downstream terminus (i.e. mouth) and moving in an upstream direction.

- In terms of "importance":

- Little Cuyahoga River and West Branch Cuyahoga River articles,

- followed by the other creeks going from mouth to upstream.

References

- {{cite news|last1=Glanville|first1=Justin|title=A River Runs Through It|url=https://www.kent.edu/magazine/news/river-runs-through-it|accessdate=March 21, 2017|work=Kent State Magazine|issue=Spring 2015|publisher=Kent State University|date=January 22, 2015|language=en}}

- "Cuyahoga River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "East Branch Cuyahoga River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "West Branch Cuyahoga River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Upper Cuyahoga River Watershed TMDLs Figure 2. Schematic Representation of the Upper Cuyahoga Watershed" (PDF). Ohio EPA. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2009.

- "Map of Ohio watersheds". Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (GIF) on March 11, 2007.

- United States Geological Survey Hydrological Unit Code: 04-11-00-02

- Feran, Tom (February 13, 2004). "Shooing the hog out of Cuyahoga". The Plain Dealer.

- Feran, Tom (June 2, 2006). "It's a Cleveland thing, so to speak". The Plain Dealer.

- Siegel, Robert; Block, Melissa (June 23, 2009). "Letters: Cuyahoga River". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- McIntyre, Michael K. (June 28, 2009). "How to pronounce 'Cuyahoga' turns into a national debate: Tipoff". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- "The Myth of the Cuyahoga River Fire, Podcast and transcript, Episode 241". Science History Institute. May 28, 2019. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Maag, Christopher (June 20, 2009). "From the Ashes of '69, Cleveland's Cuyahoga River Is Reborn". The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Johnston, Laura (April 16, 2019). "Cuyahoga named River of the Year". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: CUYAHOGA RIVER". ech.case.edu. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- David Brose (January 24, 2013). "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: EXPLORATIONS". ech.case.edu. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- "The Cuyahoga River Watershed: Proceedings of a symposium commemorating the dedication of Cunningham Hall." Kent State University, November 1, 1968.

- Adler, Jonathan H. (2003). "Fables of the Cuyahoga: Reconstructing a History of Environmental Protection" (PDF). Fordham Environmental Law Journal. Case Western Reserve University. 14: 95–98, 103–104. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 22, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- "Cuyahoga River Area of Concern". Environmental Protection Agency.

- Urycki, Mark (June 18, 2019). "50 Years Later: Burning Cuyahoga River Called Poster Child For Clean Water Act". Morning Edition on NPR. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- "The Cities: The Price of Optimism". Time. August 1, 1969. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- "REF 51 "U.S. Opens Probe Here on Pollution" The Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio, December 1970". Home | Robert Walter Jones J.D. Library and Archive. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- "Press Conference John Mitchell 12-18-1970" (PDF).

- "REF 53 "Charges J&L With Pollution" (AP) The Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio, December 31st, 1970". Home | Robert Walter Jones J.D. Library and Archive. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- "REF 52 U.S. Jury Indicts CEI on Ash Dumping in Lake" by Brian Williams, The Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio, December 1970". Home | Robert Walter Jones J.D. Library and Archive. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- "REF 54 "Pollution Suits Hit U.S. Steel" by Brian Williams, The Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio, December, 1970". Home | Robert Walter Jones J.D. Library and Archive. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- "REF 56 "U.S. Sues Metals Firm as Polluter" The Plain Dealer, Cleveland, Ohio, October 14, 1971". Home | Robert Walter Jones J.D. Library and Archive. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- "Cuyahoga: Ohio's American Heritage River" (PDF). Cuyahoga River Community Planning Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, Cuyahoga River Area of Concern, June 20, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- Johnston, Laura (March 18, 2019). "Cuyahoga River fish safe to eat, Ohio EPA says". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Cuyahoga River Area of Concern". Environmental Protection Agency.

- Scott, Michael (January 25, 2009). "Brecksville dam bad for river, good for canal". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- McCarty, James F. (October 18, 2017). "Brecksville dam demolition not expected until 2019; fishermen welcome the one-year respite". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- Ohio EPA, Biological and Water Quality Study of the Cuyahoga River and Selected Tributaries Archived September 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, August 15, 1999. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "Beacon Journal: Search Results". nl.newsbank.com. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- Kent Environmental Council, Newsletter June 2005 Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- Downing, Bob (July 28, 2005). "Hydropower plan hits rough water". Akron Beacon Journal.

- Potter, Mark R (June 3, 2007). "Still no Gorge park access for company". Cuyahoga Falls News-Press. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007.

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Letter to Metro Hydroelectric Company, June 14, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- Bob Downing, Akron Beacon-Journal, Agency Dismisses Company's Park Plans, June 16, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- Downing, Bob (June 12, 2009). "Foes help sink Gorge hydro project". Akron Beacon Journal.

- Conn, Jennifer. "Plan Unveiled to Bring Down the Gorge Dam by 2023". www.wksu.org. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- Walsh, Ellin (August 2, 2012). "Dismantling of dams along Cuyahoga River to get under way in September". Falls News Press. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- Deike, John (December 22, 2011). "Downtown dams will come down". Cuyahoga Falls Patch. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Wiandt, Steve (November 27, 2011). "Downtown dams will come down". Falls News Press. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- "Construction zone will soon be set up for removal of two Cuyahoga Falls dams". Cuyahoga Falls News-Press. May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- Conn, Jennifer (April 8, 2019). "Cuyahoga Falls to Consider New Ways to Control Erosion along Cuyahoga River". WKSU. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- Summit County, Ohio, Munroe Falls Dam Archived April 6, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- NewsNet5, Crews Unearth Natural Waterfall Archived November 7, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, September 13, 2005. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- Downing, Bob (September 22, 2005). "Munroe Falls dam to stand, but shorter". Akron Beacon Journal.

- AP / Cleveland Plain Dealer. Dam removal to return Cuyahoga to natural, free-flowing state. Posted September 29, 2005; retrieved October 6, 2005.

- City of Kent, Ohio, Cuyahoga River Restoration Project FINAL SUMMARY. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- White, Richard (1991). The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge University Press. pp. 188–189, fn 4. ISBN 0-521-37104-X.

white river french indiana 1744.

- "3745-1-26 Cuyahoga river" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency.

- "Lower Cuyahoga River Watershed TMDLs Figure 2. Schematic of the Lower Cuyahoga River Watershed" (PDF). Ohio EPA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2008.

- Ohio and Erie Canal diversion dam manually plotted in Google.

- "Gorge Metropolitan Park Dam". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009. manually adjusted in Google

- "Middle Cuyahoga TMDL, Figure 2. Schematic of the Middle Cuyahoga River" (PDF). Ohio EPA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2008.

- "Cuyahoga Falls Low Head Dam". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009. manually adjusted in Google

- Kent dam manually plotted from Google Maps

- "Lake Rockwell Dam". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009. manually adjusted in Google

- "Old River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Kingsbury Run (Cuyahoga River)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Morgan Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Burk Branch". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Big Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "West Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Mill Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Tinkers Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Chippewa Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Brandywine Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Stanford Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Grannys Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Slipper Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Boston Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Haskell Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Salt Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Dickerson Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Langes Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Robinson Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Furnace Run". Cuyahoga River Community Planning Organization. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009.

- "Furnace Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Yellow Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Woodward Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Sand Run". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Mud Brook (Cuyahoga River)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Little Cuyahoga River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Fish Creek (Cuyahoga River)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Plum Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Breakneck Creek (Cuyahoga River)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Eckert Ditch (Cuyahoga River)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Yoder Ditch". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Harper Ditch (Cuyahoga River)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Black Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Sawyer Brook". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "Bridge Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

General references

- "Lower Cuyahoga River Watershed TMDLs, Appendix D. Aquatic Life Use Attainment Status for Stations Sampled in the Cuyahoga River Basin July–September, 1999–2000" (PDF). Ohio EPA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2008.

- Keren, Phil (2004). "Removal could be in dam's future". Cuyahoga Falls News-Press.

- Keren, Phil (2005). "Change proposed for Gorge Dam". Cuyahoga Falls News-Press.

- Passell, Lauren (2005). "Metro Parks discuss future of Gorge Dam". Cuyahoga Falls News-Press.

- Akron Beacon Journal Editorial (2005). All Wet. Retrieved July 29, 2005.

- AP / Cleveland Plain Dealer. Dam removal to return Cuyahoga to natural, free-flowing state. Posted September 29, 2005; retrieved October 6, 2005.

- Kuehner, John C (March 2, 2006). "Hydroelectric project has upstream battle". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on August 22, 2007.

- Potter, Mark R (June 3, 2007). "Still no Gorge park access for company". Cuyahoga Falls News-Press. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuyahoga River. |

- Cuyahoga River Community Planning Organization

- Cuyahoga Valley

- Friends of the Crooked River

- National Whitewater River Inventory

- Lower Cuyahoga Gorge (below the Ohio Edison Dam)

- Upper Cuyahoga Gorge (Cuyahoga Falls, above the Dam)

- Kent to Munroe Falls

- Ira Rd. to Peninsula

- Peninsula to Boston Mills

- Cuyahoga River and Cuyahoga River Fire entries from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

- Year of the River, The Plain Dealer special section commemorating the 40th anniversary of the 1969 fire