Clobazam

Clobazam (marketed under the brand names Frisium, Urbanyl, Onfi, and Tapclob) is a benzodiazepine class medication that was patented in 1968.[1] Clobazam was first synthesized in 1966 and first published in 1969. Clobazam was originally marketed as an anxioselective anxiolytic since 1970[2][3] and an anticonvulsant since 1984.[4] The primary drug-development goal was to provide greater anxiolytic, anti-obsessive efficacy with fewer benzodiazepine-related side effects.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Frisium, Urbanol, Onfi, Tapclob |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets and Oral Suspension) |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 87% (oral) |

| Protein binding | 80–90% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | clobazam: 36–42 hours, N-desmethylclobazam: 71–82h |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.040.810 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H13ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 300.74 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Medical uses

Clobazam is used for epilepsy. It is unclear if there are any benefits to clobazam over other seizure medications for children with Rolandic epilepsy or other epileptic syndromes.[5]

As of 2005, clobazam is approved in Canada for add-on use in tonic-clonic, complex partial, and myoclonic seizures.[6] Clobazam is approved for adjunctive therapy in complex partial seizures[7] certain types of status epilepticus, specifically the mycolonic, myoclonic-absent, simple partial, complex partial, and tonic varieties,[8] and non-status absence seizures. It is also approved for treatment of anxiety.

In India, clobazam is approved for use as an adjunctive therapy in epilepsy and in acute and chronic anxiety.[9] In Japan, clobazam is approved for adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant epilepsy featuring complex partial seizures.[10] In New Zealand, clobazam is marketed as Frisium[11] In the United Kingdom clobazam (Frisium) is approved for short-term (2–4 weeks) relief of acute anxiety in patients who have not responded to other drugs, with or without insomnia and without uncontrolled clinical depression.[12] It was not approved in the US until October 25, 2011, when it was approved for the adjunctive treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome in patients 2 years of age or older.[13]

It is also approved for adjunctive therapy for epilepsy in patients who have not responded to first-line drugs and in children who are refractory to first-line drugs. It is not recommended for use in children between the ages of six months and three years, unless there is a compelling need.[12] In addition to epilepsy and severe anxiety, clobazam is also approved as a short-term (2–4 weeks) adjunctive agent in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders to manage anxiety or agitation.[12]

Clobazam is also available as an oral suspension in the UK, under the trade name of Tapclob.

Clobazam is sometimes used for refractory epilepsies. However, long-term prophylactic treatment of epilepsy may have considerable drawbacks, most importantly decreased antiepileptic effects due to tolerance which may render long-term therapy less effective.[14] Other antiepileptic drugs may therefore be preferred for the long-term management of epilepsy. Furthermore, benzodiazepines may have the drawback, particularly after long-term use, of causing rebound seizures upon abrupt or over-rapid discontinuation of therapy forming part of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.

Contraindications

Clobazam should be used with great care in patients with the following disorders:

- Myasthenia gravis.

- Sleep apnea.

- Severe liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatitis.[15]

- Severe Respiratory Insufficiency.

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[16]

Side effects

Common

Common side effects include fever, lethargy, sleepiness, drooling, and constipation.[17]

Warnings and Precautions

In December 2013 the FDA added warnings to the label for clobazam, that it can cause serious skin reactions, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis, especially in the first eight weeks of treatment.[18]

Drug interactions

Overdose

Overdose and intoxication with benzodiazepines, including clobazam, may lead to CNS depression, associated with drowsiness, confusion, and lethargy, possibly progressing to ataxia, respiratory depression, hypotension, and coma or death. The risk of a fatal outcome is increased in cases of combined poisoning with other CNS depressants, including alcohol.[19]

Abuse potential and addiction

Classic (non-anxioselective) benzodiazepines in animal studies have been shown to increase reward seeking behaviours which may suggest an increased risk of addictive behavioural patterns.[20] Clobazam abuse has been reported in some countries, according to a 1983 World Health Organisation report.[21]

Dependence and withdrawal

In humans, tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clobazam may occur[22] and withdrawal seizures may occur during abrupt or overrapid withdrawal.[23]

Clobazam as with other benzodiazepine drugs can lead to physical dependence, addiction, and what is known as the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal from clobazam or other benzodiazepines after regular use often leads to withdrawal symptoms which are similar to those seen during alcohol and barbiturate withdrawal. The higher the dosage and the longer the drug is taken, the greater the risk of experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Benzodiazepine treatment should only be discontinued via a slow and gradual dose reduction regimen.[24]

Pharmacology

Clobazam is predominantly a positive allosteric modulator at the GABAA receptor with some speculated additional activity at sodium channels and voltage-sensitive calcium channels.[25]

Like other 1,5-benzodiazepines (For example, arfendazam, lofendazam, or CP-1414S), the active metabolite N-desmethyl-clobazam has less affinity for the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor compared to the 1,4-benzodiazepines. It has higher affinity for α2 containing receptors, where it has positive modulatory activity.[26][27]

In a double-blind placebo-controlled trial published in 1990 comparing it to clonazepam, 10 mg of clobazam was shown to be less sedative than either 0.5 mg or 1 mg of clonazepam.[28]

The α1 subtype of the GABAA receptor, was shown to be responsible for the sedative effects of diazepam by McKernan et al. in 2000, who also showed that its anxiolytic and anticonvulsant properties could still be seen in mice whose α1 receptors were insensitive to diazepam.[29]

In 1996, Nakamura et al. reported that clobazam and its active metabolite, N-desmethylclobazam (norclobazam), work by enhancing GABA-activated chloride currents at GABAA-receptor-coupled Cl− channels. It was also reported that these effects were inhibited by the GABA antagonist flumazenil, and that clobazam acts more efficiently in GABA-deficient brain tissue.[30]

Chemistry

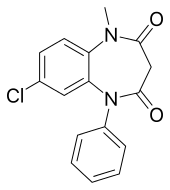

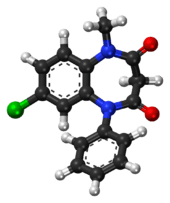

Clobazam is a 1,5-benzodiazepine, meaning that its diazepine ring has nitrogen atoms at the 1 and 5 positions (instead of the usual 1 and 4).[33]

It is not soluble in water and is available in oral form only.[25][19]

History

Clobazam was discovered at the Maestretti Research Laboratories in Milan and was first published in 1969;[34] Maestretti was acquired by Roussel Uclaf[35] which became part of Sanofi.

See also

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Effects of long-term benzodiazepine use

References

- T3DB, "". "T3DB Clozabam". T3DB.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Humayun MJ, Samanta D, Carson RP (2020). "Clobazam". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31082087.

- Freche C (April 1975). "[Study of an anxiolytic, clobazam, in otorhinolaryngology in psychosomatic pharyngeal manifestations]". Semaine des Hopitaux. Therapeutique. 51 (4): 261–3. PMID 5777.

- "Clobazam in treatment of refractory epilepsy: the Canadian experience. A retrospective study. Canadian Clobazam Cooperative Group". Epilepsia. 32 (3): 407–16. 1991. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb04670.x. PMID 2044502.

- Arya, Ravindra; Giridharan, Nisha; Anand, Vidhu; Garg, Sushil K. (11 July 2018). "Clobazam monotherapy for focal or generalized seizures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD009258. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009258.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6513499. PMID 29995989.

- Epilepsy Ontario (2005). "Clobazam". Medications. Archived from the original on 2006-08-18. Retrieved 2006-03-04.

- Larrieu JL, Lagueny A, Ferrer X, Julien J (December 1986). "[Epilepsy with continuous discharges during slow-wave sleep. Treatment with clobazam]". Revue d'Electroencephalographie et de Neurophysiologie Clinique. 16 (4): 383–94. doi:10.1016/S0370-4475(86)80028-4. PMID 3103177.

- Gastaut H, Tinuper P, Aguglia U, Lugaresi E (December 1984). "[Treatment of certain forms of status epilepticus by means of a single oral dose of clobazam]". Revue d'Electroencephalographie et de Neurophysiologie Clinique. 14 (3): 203–6. doi:10.1016/S0370-4475(84)80005-2. PMID 6528075.

- "Frisium Press Kit". Aventis Pharma India. Archived from the original on 2005-03-05. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- Shimizu H, Kawasaki J, Yuasa S, Tarao Y, Kumagai S, Kanemoto K (July 2003). "Use of clobazam for the treatment of refractory complex partial seizures". Seizure. 12 (5): 282–6. doi:10.1016/S1059-1311(02)00287-X. PMID 12810340.

- Epilepsy New Zealand (2000). "Antiepileptic Medication". Archived from the original on 11 March 2005. Retrieved 11 July 2005.

- sanofi-aventis (2002). "Frisium Tablets 10 mg, Summary of Product Characteristics from eMC". electronic Medicines Compendium. Medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2005.

- "FDA Approves ONFI™ (clobazam) for the Adjunctive Treatment of Seizures Associated with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome in Patients Two Years and Older" (Press release). Lundbeck. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- Isojärvi JI, Tokola RA (December 1998). "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 42 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): 80–92. PMID 10030438.

- Monjanel-Mouterde S, Antoni M, Bun H, Botta-Frindlund D, Gauthier A, Durand A, Cano JP (June 1994). "Pharmacokinetics of a single oral dose of clobazam in patients with liver disease". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 74 (6): 345–50. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb01371.x. PMID 7937568.

- Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Francaises. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- "Clobazam label" (PDF). December 2014.

- FDA. December 3rd, 2013 FDA Drug Safety Podcast: FDA warns of serious skin reactions with the anti-seizure drug Onfi (clobazam) and has approved label changes

- Fruchtengarten L Inchem - Clobazam. Created July 1997, Reviewed 1998.

- Thiébot MH, Le Bihan C, Soubrié P, Simon P (1985). "Benzodiazepines reduce the tolerance to reward delay in rats". Psychopharmacology. 86 (1–2): 147–52. doi:10.1007/BF00431700. PMID 2862657.

- WHO Review Group (1983). "Use and abuse of benzodiazepines". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 61 (4): 551–62. PMC 2536139. PMID 6605211.

- Loiseau P (1983). "[Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy]". L'Encephale. 9 (4 Suppl 2): 287B–292B. PMID 6373234.

- Robertson MM (1986). "Current status of the 1,4- and 1,5-benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy: the place of clobazam". Epilepsia. 27 Suppl 1: S27-41. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb05730.x. PMID 3527689.

- MacKinnon GL, Parker WA (1982). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 9 (1): 19–33. doi:10.3109/00952998209002608. PMID 6133446.

- Ochoa JG (2005). "Antiepileptic Drugs: An Overview. GABA Receptor Agonists". Drugs and Diseases. Medccape. Retrieved 10 July 2005.

- Ralvenius WT, Acuña MA, Benke D, Matthey A, Daali Y, Rudolph U, et al. (October 2016). "The clobazam metabolite N-desmethyl clobazam is an α2 preferring benzodiazepine with an improved therapeutic window for antihyperalgesia". Neuropharmacology. 109: 366–375. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.07.004. PMC 4981430. PMID 27392635.

- Nakajima H (August 2001). "[A pharmacological profile of clobazam (Mystan), a new antiepileptic drug]". Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica. 118 (2): 117–22. doi:10.1254/fpj.118.117. PMID 11530681.

- Wildin JD, Pleuvry BJ, Mawer GE, Onon T, Millington L (February 1990). "Respiratory and sedative effects of clobazam and clonazepam in volunteers". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 29 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03616.x. PMC 1380080. PMID 2106335.

- McKernan RM, Rosahl TW, Reynolds DS, Sur C, Wafford KA, Atack JR, et al. (June 2000). "Sedative but not anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are mediated by the GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subtype". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (6): 587–92. doi:10.1038/75761. PMID 10816315.

- Nakamura F, Suzuki S, Nishimura S, Yagi K, Seino M (August 1996). "Effects of clobazam and its active metabolite on GABA-activated currents in rat cerebral neurons in culture". Epilepsia. 37 (8): 728–35. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00643.x. PMID 8764810.

- Contin M, Sangiorgi S, Riva R, Parmeggiani A, Albani F, Baruzzi A (December 2002). "Evidence of polymorphic CYP2C19 involvement in the human metabolism of N-desmethylclobazam". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 24 (6): 737–41. doi:10.1097/00007691-200212000-00009. PMID 12451290.

- Giraud C, Tran A, Rey E, Vincent J, Tréluyer JM, Pons G (November 2004). "In vitro characterization of clobazam metabolism by recombinant cytochrome P450 enzymes: importance of CYP2C19". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 32 (11): 1279–86. doi:10.1124/dmd.32.11.1279. PMID 15483195.

- Shorvon SD (March 2009). "Drug treatment of epilepsy in the century of the ILAE: the second 50 years, 1959-2009". Epilepsia. 50 Suppl 3: 93–130. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02042.x. PMID 19298435.

- Hanks GW (1979). "Clobazam: pharmacological and therapeutic profile". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 7 Suppl 1: 151S–155S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb04685.x. PMC 1429523. PMID 35198.

- Zirulia G (2014). L'industria delle Medicine. EDRA LSWR. ISBN 9788821439049.

Further reading

- Dean L (September 2019). "Clobazam Therapy and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 31550100.