Burnley F.C.

Burnley Football Club (/ˈbɜːrnli/) is a professional association football club based in Burnley, Lancashire, England. Founded on 18 May 1882, the team originally played only friendly matches until it entered the FA Cup for the first time in 1885–86. The club currently competes in the Premier League, the first tier of English football. Nicknamed "the Clarets", due to the dominant colour of the home shirts, Burnley was one of the twelve founding members of the Football League in 1888. The club's emblem is based on the town's crest, with a Latin motto Pretiumque et Causa Laboris ("The Prize and the Cause of [Our] Labour").

| ||||

| Full name | Burnley Football Club | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Clarets | |||

| Short name | BUR, BFC | |||

| Founded | 18 May 1882 | |||

| Ground | Turf Moor | |||

| Capacity | 21,944 | |||

| Chairman | Mike Garlick | |||

| Manager | Sean Dyche | |||

| League | Premier League | |||

| 2018–19 | Premier League, 15th of 20 | |||

| Website | Club website | |||

| ||||

Burnley has been champions of England twice, in 1920–21 and 1959–60, has won the FA Cup once, in 1914, and has won the Community Shield twice, in 1960 and 1973. The club has been runners-up in the First Division (now the Premier League) twice, in 1919–20 and 1961–62, and has finished runners-up two times in the FA Cup, in 1947 and 1962. The Clarets also reached the 1961 quarter-finals of the European Cup. Burnley is one of only five teams to have won all top four professional divisions of English football, along with Wolverhampton Wanderers, Preston North End, Sheffield United and Portsmouth.

Burnley has played home games at Turf Moor since 17 February 1883, after it had moved from the original premises at Calder Vale. The club colours of claret and blue were adopted prior to the 1910–11 season in tribute to the dominant club of English football at the time, Aston Villa. Burnley has a long-standing rivalry with nearby club Blackburn Rovers, with whom it contests the East Lancashire Derby.

History

Early years (1882–1912)

On 18 May 1882, members of Burnley Rovers Rugby Club gathered at the Bull Hotel in Burnley to vote for a shift from rugby union to association football, since other sports clubs in the area had changed their codes to association football and more income could be generated by playing football.[1] A large majority voted in favour of change of sports. A short time later, the club secretary, George Waddington, met with his committee and put forward another proposal, to drop "Rovers" from the club's name, thereby "adopting the psychological high ground over many other local clubs by carrying the name of the town", which the committee members unanimously agreed on.[2]

On 10 August, Burnley Football Club played its first-ever match as an association football club against local club Burnley Wanderers, winning 4–0. The club played the match in a blue and white kit, the colours of the former rugby club, at Calder Vale, which had been the home of Rovers Rugby Club.[3] Burnley's first competitive game was in October 1882 against Astley Bridge in the Lancashire Challenge Cup, that game ending in an 8–0 defeat.[4] In February 1883, the club was invited by Burnley Cricket Club to move to a pitch adjacent to the cricket field at Turf Moor. Both clubs have remained there since, and only Lancashire rivals Preston North End has continuously occupied the same ground for longer.[5]

That same year saw Burnley win its first honour as an association football club. The "Dr Dean Trophy" (later known as the "Hospital Cup"), a knockout competition between amateur clubs in the Burnley area, was won in a final played at the new home ground.[6] The tournament was created as a fundraiser for the town's proposed new hospital, and Burnley won the cup on multiple occasions in the following years.[6] By the end of 1883, the club turned professional and signed many Scottish players, who were regarded as the better footballers at the time.[4] As a result of turning professional, Burnley renounced joining the Football Association (FA) and its FA Cup, since the association refused to allow professional players.[7] In 1884, Burnley had led a group of 35 other clubs in forming a breakaway, the British Football Association, to challenge the supremacy of the FA.[7][8] This threat of secession was to lead to the legalisation of professionalism on 20 July 1885 by the FA, making the new body redundant.[8] Burnley's main rivals at this point were neighbours Padiham and the fiery matches between the two attracted up to 10,000 fans.[4]

Burnley made its first appearance in the FA Cup in 1885–86, but was ignominiously beaten 11–0 when eligibility restrictions meant that the reserve side had to be fielded against Darwen Old Wanderers, as professional players were nevertheless barred from playing in the FA Cup that year.[9] A year later, on 13 October 1886, Turf Moor became the first professional ground to be visited by a member of the Royal Family, when Queen Victoria's grandson, Prince Albert Victor, was in attendance for a match between Burnley and Bolton Wanderers, after he opened a new hospital in the town.[10] When it was decided to found the Football League for the 1888–89 season, Burnley was among the twelve founders of that competition, and one of the six clubs based in Lancashire.[11] Burnley's William Tait became the first player to score a hat-trick in league football in only the second match, when his three goals gave the Clarets an away win against Bolton Wanderers.[12] The club eventually finished ninth in the first season of the league, but only one place from bottom in 1889–90, following a 17-game winless streak at the start of the season.[13] That season did, however, present Burnley with its first professional honours, winning the Lancashire Cup with a 2–0 final victory over local rivals Blackburn Rovers.[14] Burnley was at this point also known as "The Turfites", "Moorites" or "Royalites" as a result of the name of their ground and the royal connection.[15]

Before the club won a trophy again, Burnley was relegated to the Second Division for the first time in 1896–97. The team responded to this by winning the league the next season, losing only two of 30 matches along the way before gaining promotion through a play-off series, then known as test matches.[16] Burnley and First Division club Stoke City both entered the last match, to be played between the two teams, needing a draw for promotion (or in Stoke's case to retain their First Division place). A 0–0 draw ensued, reportedly "The match without a shot at goal",[17] and the league immediately withdrew the test match system in favour of automatic promotion and relegation, after Burnley director and Football League Management Committee member Charles Sutcliffe had already made a proposal to discontinue the test matches.[18] Ironically, the league also decided to expand the top division after the test match series of 1897–98 and the other two teams also went into the top division for the following year, negating the effect of Burnley and Stoke City's reputed collusion.[17][19]

Burnley was relegated again in 1899–1900 and found itself at the centre of a controversy when the club's goalkeeper, Jack Hillman, attempted to bribe the opponents, Nottingham Forest, in the last match of the season, resulting in his suspension for the whole of the following season. It was the earliest recorded case of match fixing in football.[20] During the first decade of the 20th century, Burnley continued to play in the Second Division, even finishing in bottom place in 1902–03 (but was re-elected).[21] Alarming performances on the field mixed with a considerable debt saw manager Ernest Mangnall leave the club for Manchester United in October 1903.[21] In 1907, 30-year-old Burnley supporter Harry Windle was invited onto the Burnley board to become a director. Two years later, he was elected chairman, and under his guidance Burnley's finances turned around.[22] The club reached the quarter-finals of the 1908–09 FA Cup, in which it was eliminated by Manchester United in a replay. In the original match, on a snowy Turf Moor pitch, Burnley had lead 1–0, when the match was abandoned after 72 minutes.[23] In 1910, Mangnall's successor Spen Whittaker died, after he fell off a train.[24] Under new manager John Haworth, Burnley changed its colours from green to the claret and sky blue of Aston Villa, the most successful club in England at the time, for the 1910–11 season, as Haworth and the Burnley committee believed it might bring a change of fortune.[25] The tides did indeed turn the following season, when only a loss in the last game of the season denied the club promotion.[26]

Clarets' glory either side of the First World War (1912–1946)

Burnley continued to improve, as the 1912–13 season saw them win promotion to the First Division once more, as well as reaching the FA Cup semi-final, only to lose to Sunderland. The next season was one of consolidation in the top flight, but more importantly the first major honour, the FA Cup, was won, against fellow Lancastrians Liverpool in the final (1–0).[27] Ex-Evertonian Bert Freeman, whose father travelled from Australia to see his son play in the final,[28] scored the only goal, as Burnley became the first club to beat five First Division clubs in one cup season.[29] This was the last final to be played at Crystal Palace and King George V became the first reigning monarch to attend an FA Cup Final and to present the cup to the winning captain, in this case to Tommy Boyle.[29]

Burnley finished fourth in the First Division in 1914–15, before English football was suspended during wartime. Upon resumption of full-time football in 1919–20, Burnley finished second in the First Division to West Bromwich Albion, but this was not a peak, merely presaging Burnley's first ever league championship in 1920–21.[30] Burnley lost the opening three matches that season before going on a 30-match unbeaten run, a record for unbeaten games in a single season that lasted until Arsenal went unbeaten through the whole of the 2003–04 season.[31] Burnley could not retain the title and finished third the following season. The successful John Haworth became the second Burnley manager to die while in office in 1924, when he died of pneumonia.[32] In April 1926, centre-forward Louis Page scored a club record six goals in an away league match against Birmingham City.[33] Thereafter followed a steady deterioration of their position, with only fifth place in 1926–27 offering respite from a series of near-relegations which culminated in demotion in 1929–30.[34] Burnley struggled in the second tier, narrowly avoiding a further relegation in 1931–32 by two points. The years through to the outbreak of the Second World War were characterised by uninspiring league finishes, broken only by an FA Cup semi-final appearance in 1934–35 and the arrival (and equally swift departure) of centre-forward Tommy Lawton.[35] Burnley participated in the varying football leagues that continued throughout the war, but it was not until the 1946–47 season that league football proper was restored.[36]

Golden, progressive era under Bob Lord, Alan Brown and Harry Potts (1946–1976)

In the first season of post-war league football, Burnley gained promotion through second place in the Second Division. The club's defence was nicknamed "The Iron Curtain", since they only conceded 29 goals in 42 league matches.[37] Additionally, there was a run to the FA Cup Final for the second time, with Aston Villa, Coventry City, Luton Town, Middlesbrough and Liverpool being defeated before Charlton Athletic beat Burnley 1–0 after extra time at Wembley.[38] Burnley immediately made an impact in the top division, finishing third in 1947–48 as it began to assemble a team capable of regularly aiming for honours.[39]

From 1955 to 1981, under the reign of lifelong Burnley supporter and newly appointed chairman Bob Lord, later described as "the Khrushchev of Burnley" as a result of his authoritative attitude,[40] the club became one of the most progressive around.[41][42] On account of manager Alan Brown, appointed in 1954, and Lord, Burnley became one of the first clubs to build a purpose-built training centre (Gawthorpe), which opened its doors on 25 July 1955,[43] while most teams trained on public parks or at their own grounds.[41] Gawthorpe was built on the outskirts of the town and as well as using paid labour, manager Brown helped to dig out the ground himself.[44] Brown also "volunteered" several of his players to help out. Further, Burnley became, after foundations were again laid by Lord and Brown,[40][45] renowned for its youth policy and scouting system, which yielded many young players over the years such as Jimmy Adamson, Jimmy McIlroy, John Connelly, Willie Morgan and Martin Dobson.[46][47] An acclaimed scout employed by Burnley during this period was Jack Hixon, who was based in North East England and beyond, and scouted many players, including Brian O'Neil, Ralph Coates and Dave Thomas.[48]

In his relatively short spell at the club from 1954 to 1957, Brown also introduced short corners and a huge array of free kick routines, which were soon copied across the land.[49] The 1955–56 season saw Burnley reach the fourth round of the FA Cup, where the club was knocked out by Chelsea after four replays.[50] In 1956–57, Ian Lawson, a product of the Burnley youth academy, scored a record four goals on his debut as a 17-year-old versus Chesterfield in third round of the FA Cup.[51] That same season saw a club record 9–0 victory over New Brighton in the FA Cup fourth round[52] — despite missing a penalty — and the following season former Burnley player Harry Potts became manager. The team of this period mainly revolved around the midfield duo of one-club man Jimmy Adamson and playmaker Jimmy McIlroy. Potts often employed the, at the time unfashionable, 4–4–2 formation and he introduced Total Football to English football in his first managerial seasons at Burnley.[53][54]

Burnley endured a tense 1959–60 season in which Tottenham Hotspur and Wolverhampton Wanderers were the other protagonists in the chase for the league title. The club ultimately clinched its second league championship on the last day of the season at Maine Road with a 2–1 victory against Manchester City with goals from Brian Pilkington and Trevor Meredith.[55] Although the team had been in contention all season, Burnley had never led the table until this last match was played out.[42] Potts only used eighteen players throughout the whole season, as John Connelly became Burnley's top scorer with 20 goals.[53] The Lancastrians' title-winning squad only cost £13,000 in transfer fees — £8,000 on McIlroy in 1950 and £5,000 on left-back Alex Elder in 1959.[46] The other players of the team each came from the Burnley youth academy.[46][42] The town of Burnley became the smallest to have an English first tier champion, since it only counted 80,000 inhabitants (the town had about 100,000 people in 1921).[56] After the season finished, Burnley went to the United States to participate in the inaugural international football tournament in North America, the International Soccer League.[57]

The following season Burnley played in European competition for the first time, in the European Cup,[58] beating former finalists Reims, before losing to Hamburger SV in the quarter-finals. The club lost the FA Cup semi-final to Tottenham and finished fourth in the league. Burnley finished the 1961–62 season as runners-up (after winning only two of the last thirteen league matches)[59] to newly promoted Ipswich Town and had a run to the FA Cup Final, where a Jimmy Robson goal, the 100th FA Cup Final goal at Wembley,[60] was the only reply to three goals from Tottenham. Jimmy Adamson was, however, named Footballer of the Year in English football after the season ended.[61] Burnley also had, due to their success, several players with international caps in this period, including, for England Ray Pointer, Colin McDonald, and John Connelly (a member of the 1966 World Cup squad), for Northern Ireland Jimmy McIlroy and for Scotland Adam Blacklaw.[62]

Nonetheless, although far from a two-man team, the controversial departure of McIlroy to Stoke City and retirement of Adamson coincided with a decline in fortunes. Even more damaging was the impact of the abolition of the maximum wage in 1961, meaning clubs from small towns, like Burnley, could no longer compete financially with teams from bigger towns and cities.[63] The club managed, however, to retain a First Division place throughout the decade finishing third in 1965–66, with Willie Irvine becoming the league's top goal scorer that season,[64] and reaching the semi-final of the League Cup in 1968–69. Burnley had also reached the quarter-finals of the 1966–67 Fairs Cup, in which it was knocked out by German side Eintracht Frankfurt.[65]

Since the remainder of the decade was one of mid-table mediocrity, Potts was replaced by Adamson as manager in 1970 after a 12-year spell. Adamson was unable to halt the slide and relegation followed in 1970–71 ending a long unbroken top flight spell of 24 consecutive seasons during which, more often than not, Burnley had been in the upper reaches of the league table.[66] Burnley won the Second Division title in 1972–73 with Adamson still in charge. As a result, Burnley was invited to play in the 1973 FA Charity Shield where it emerged as winners against the reigning holders of the shield, Manchester City.[67] In the First Division, led by elegant playmaker Martin Dobson, the side managed to finish sixth in 1973–74 as well as reaching another FA Cup semi-final; this time losing out to Newcastle United.[68] The following season the club achieved tenth place, despite Dobson being sold to Everton during the campaign, but were victims of one of the great FA Cup shocks of all time when Wimbledon, then in the Southern League, beat Burnley 1–0 at Turf Moor.[69] Relegation from the First Division in 1975–76 saw the end of Adamson's tenure as manager.[66] Over the past seasons, as a result of declining home attendances combined with a growing debt, Burnley had to sell their best players, which ultimately led to a rapid fall through the divisions.[70]

Decline and near oblivion (1976–1987)

Three nondescript seasons in the Second Division followed before relegation to the Third Division for the first time in 1979–80. Of 42 league games, Burnley could not manage a win in either the first or last 16. In September 1981, with the club in the Third Division relegation zone, and close to bankruptcy, Lord decided to retire.[71] The remainder of the season, under the management of former Burnley player Brian Miller,[72] saw only three more defeats since October, as Burnley was promoted as champions in its centenary year.[73] However, this return was short-lived, lasting only one year; albeit a year in which the team reached the quarter-finals of the FA Cup and the semi-final of the League Cup, recording victories over Tottenham and Liverpool in the latter. Burnley won 1–0 against Liverpool in the League Cup semi-final second leg, but it was not enough for an appearance in the final, as Burnley lost the first leg 3–0.[74]

Managerial changes continued to be made in an unsuccessful search for success; Miller was replaced by Frank Casper in early 1983, he by John Bond before the 1983–84 season and Bond himself by John Benson a season later.[75] The unpopular Bond was the first Burnley manager since Frank Hill (1948–1954) without a previous playing career at the club. He was criticised for signing wrong expensive players, which increased Burnley's debt, and for selling young talents Lee Dixon, Brian Laws and Trevor Steven.[76] Benson was in charge when Burnley was relegated to the fourth level of English football for the first time at the end of the 1984–85 season. It also marked the fifth relegation in the past fifteen seasons, most strikingly, finishing 21st in each of those five seasons. Martin Buchan (briefly) and then Tommy Cavanagh saw the side through 1985–86 before Miller returned for the 1986–87 season, the last match of which is known as "The Orient Game".[77]

For the 1986–87 season, the Football League had decided to introduce automatic relegation and promotion between the Fourth Division and the Conference League, the top tier of non-league football. Although, in retrospect, this has only served to blur the lines between professional and semi-professional leagues in England, at the time it was perceived that teams losing league status might never recover from this.[78] Additionally, Burnley had a new local rival in Colne Dynamoes who were rapidly progressing through the English non-league system at the same time as the former champions of England were in the lowest level of the Football League. Colne's chairman-manager, Graham White, had multiple proposals rejected by the Burnley board for a groundshare of Turf Moor, as he even attemped to buy Burnley in early 1989.[79] Two years earlier, the Burnley board had attempted to purchase almost bankrupt Welsh club Cardiff City and relocate it to Turf Moor, if Burnley would be relegated, in what would have been the Football League's first franchise operation.[80] In a disastrous season, which also saw a first round FA Cup 3–0 defeat at non-league Telford United, Burnley went into the last match needing a win against Orient. A 2–1 win, in front of about 17,000 attendees (the club's average home league attendance before the match was 2,800),[81] with goals from Neil Grewcock and Ian Britton, was enough to keep Burnley in the Fourth Division, although even that achievement still relied on a loss by Lincoln City in their last game of the season.[82]

Recovery (1987–2009)

In May 1988, Burnley was back at Wembley; this time to play Wolverhampton Wanderers in the final of the Football League Trophy, which Burnley lost 2–0. The match was attended by 80,000 people, a record for a tie between two teams from English football's fourth tier.[83] In 1990–91, the club qualified for the Fourth Division play-offs, where it was eliminated in the semi-final by Torquay United.[84] The following season, Burnley fared better, as it became champions under new manager Jimmy Mullen in the last ever season of the Fourth Division before the league reorganisation. By winning the Fourth Division title, the Clarets became only the second club to win all top four professional divisions of English football, after Wolves.[85] In 1993–94, Burnley won the new Second Division play-offs and gained promotion to the First Division. After winning 3–1 on aggregate against Plymouth Argyle in the semi-final, Burnley faced Stockport County in the final at Wembley. Burnley won 2–1, in a fierce battle (two Stockport players were sent off) in front of approximately 35,000 Burnley supporters (the total attendance was 44,806).[86] Relegation followed after one season and in 1997–98 only a last day 2–1 victory over Plymouth ensured a narrow escape from relegation back into the fourth tier. Chris Waddle was player-manager in that season and Glenn Roeder his assistant,[87] but their departures and the appointment of Stan Ternent that summer saw the club start to make further progress.[88] In 1999–2000 they finished second in the Second Division and gained promotion back to the second tier, with the club's striker and lifelong Clarets fan Andy Payton being the division's top goal scorer.[89]

Burnley immediately made an impact, as during the 2000–01 and 2001–02 seasons, it emerged as serious contenders for a promotion play-off place. In the latter season, Burnley missed the last play-off place by a single goal.[90] In early 2002, financial problems caused by the collapse of ITV Digital brought the club again close to administration.[91][92] By 2002–03, the form on the field had declined as well, despite a good FA Cup run, where it reached the quarter-finals. In June 2004, Ternent's six years as manager came to an end, narrowly avoiding relegation in his last season with a squad composed of many loanees and some players who were not entirely fit.[93] Steve Cotterill was then appointed as manager.[94] Cotterill's first year in charge produced two notable cup runs, knocking out Premier League clubs Liverpool and Aston Villa. In the 2006–07 campaign, the team set a club record for consecutive league games without a win (18 matches) stretching from December to March, meaning it had gone one fixture further than the 17 league game streak of the 1889–90 season.[95] The sequence of draws and losses was finally broken in April, as Burnley beat Plymouth Argyle 4–0 at home. After that, a short run of good form in the final weeks of the competition saw Burnley finish comfortably above the relegation places, ensuring that it remained in the Championship.[96]

The following season Burnley's poor early-season results led to the departure of Cotterill in November 2007. His replacement was St Johnstone manager Owen Coyle.[97] The 2008–09 season, Coyle's first full season in charge, ended with the Clarets' highest league finish since 1976; fifth in the Championship.[98] That was enough to qualify for the Championship play-offs. Burnley beat Reading 3–0 on aggregate in the semi-final, and the team went on to beat Sheffield United 1–0 in the final at Wembley Stadium, promoting Burnley to the Premier League, a return to the top flight after 33 years. Wade Elliott scored the vital goal in a match known as "The £50,000,000 final",[99] due to the increased revenues available to Premiership clubs after the agreement of substantially higher TV rights payments.[100] Furthermore, Burnley reached the semi-final of the League Cup for the first time in over 25 years, after beating local clubs Bury and Oldham Athletic and London-based clubs Fulham, Chelsea and Arsenal.[101] In the semi-finals Burnley faced another London club, Tottenham, and the club lost the first leg 4–1. After being up by three goals to nil at home after 90 minutes, the away goals rule comes into play after extra time has been played in the League Cup,[102] the Clarets crashed out after two Spurs goals in the last two minutes of extra time, preventing two Wembley appearances in one season.[103]

Premier League promotions, relegations and back in Europe (2009–present)

Burnley's promotion made the town of Burnley the smallest to host a Premier League club, since the rebranding of the league divisions in 1992.[104][105] Burnley started the season well, becoming the first newly promoted team in the Premier League to win its first four league home games, including a 1–0 win over defending champions Manchester United.[106] However, manager Coyle left Burnley in January 2010, to manage local rivals Bolton Wanderers. He was replaced by Brian Laws, but Burnley's form plummeted under the new manager, and the club was relegated after a single season in the Premier League.[107] Laws was dismissed in December 2010 and replaced by Bournemouth manager Eddie Howe.[108] Howe guided Burnley to an eighth-place finish in the Championship in his first season, narrowly missing out on a play-off place. Nonetheless, he left the club in October 2012 to rejoin his hometown club Bournemouth; Howe citing personal reasons for the move.[109] He was replaced in the same month by Watford manager Sean Dyche.[110]

Before the start of the 2013–14 season, Burnley was tipped as one of the relegation candidates, as Dyche had to work with a tight budget and a small squad, and they had lost top goal scorer Charlie Austin to Championship rivals Queens Park Rangers.[111] However, Burnley finished second and was automatically promoted back to the Premier League in Dyche's first full season in charge, as the new strike partnership of Danny Ings (who also won the Championship Player of the Year award) and Sam Vokes had 41 league goals between them.[112] Dyche only used 23 players throughout the season, which was the joint-lowest in the division, and he paid a transfer fee for only one player since his appointment — £400,000 on striker Ashley Barnes.[113] But again, the stay in the Premier League only lasted a single season as Burnley finished 19th out of 20 clubs and was subsequently relegated. Burnley won the Championship title on its return in 2015–16, equaling its club record of 93 points of 2013–14, and ending the season with a run of 23 league games undefeated.[114] New signing Andre Gray finished as the league's top goal scorer with 25 goals.[115]

With a combination of excellent home form with poor away results, Burnley finished the 2016–17 season in 16th place, six points above the relegation zone, and was thus ensured to play consecutive seasons in the top flight for the first time since 1975–76.[116] Burnley completed construction of a new training centre, Barnfield Training Centre, in 2017, which replaced the 60-year-old Gawthorpe.[117] Dyche was heavily involved in the design of the training centre and had willingly tailored his transfer spending as he and the board focused on the club's infrastructure and future, as former Clarets manager Brown had done in the mid-1950s when building Gawthorpe.[118] 2017–18 started off with an away win against defending champions Chelsea (3–2).[119] It was a start signal for a reversed away form, as Burnley finished the season with more points collected on the road than at home. Burnley ultimately secured an unexpected seventh place at the end of the season, the highest league finish since 1973–74, and thus qualified for the 2018–19 UEFA Europa League, meaning the club qualified for a competitive European competition for the first time in 51 years.[120] The European campaign was already over in August, as Burnley crashed out in the play-offs against Greek side Olympiacos, after it had eliminated Scottish club Aberdeen and Turkish side İstanbul Başakşehir in the previous qualifying rounds.[121]

Players

First-team squad

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Under-23s and Academy

Out on loan

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

Notable former players and managers

Players

Burnley has been represented by numerous high-profile players over the years, most notably Jimmy McIlroy and Jimmy Adamson, the latter earning the Footballer of the Year award in 1962, the first and to date only time a Burnley player has won this award.[61] Four years later, Burnley youth graduate Willie Irvine became the First Division top goal scorer, also a unique feat in the club's history.[64] Welshman Leighton James is the only Burnley player to have been included in the PFA Team of the Year while playing in the first tier, when he was selected as a member of the 1974–75 squad.[124] In total, 29 players have won full England caps during their time with the Clarets, Bob Kelly having won the most caps (11) and scored the most goals (6) for the English national team.[125]

The English Football Hall of Fame, which is housed at the National Football Museum, in Manchester, currently contains five former Burnley players: Tommy Lawton, Jimmy McIlroy, Mike Summerbee, Ian Wright and Paul Gascoigne; the latter three had, however, relatively short spells at the Clarets and were at the end of their playing careers.[126] Three of these five players, Gascoigne, Lawton and McIlroy, also featured in a list entitled "The Football League 100 Legends", as Burnley's only representatives.[127] The list was released by the Football League in 1998, to celebrate the 100th season of league football. Jimmy McIlroy was voted as PFA Fans' Favourite by Burnley fans in July 2007.[128]

In 2015, 31 "Clarets' legends" from different eras in the club's history were picked by the fans of Burnley via an online vote. The chosen players had an artwork depicting them hung beside the turnstiles of Turf Moor. It was a cooperation between the club and members of the Burnley supporters' clubs, to "improve the appearance of the ground and provide a vivid history of some of the greatest players to wear a claret and blue shirt".[129] The Clarets' first international, John Yates, had to be omitted because no suitable image of him could be found, therefore giving his spot to George Halley. Including Yates, the following 32 players were picked:[130][131]

|

|

|

Player of the Year Award

As voted by the club's supporters at the end of every season.[132]

| Year | Position | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| 2002–03 | FW | |

| 2003–04 | FW | |

| 2004–05 | DF | |

| 2005–06 | DF | |

| 2006–07 | MF | |

| 2007–08 | MF | |

| 2008–09 | DF | |

| 2009–10 | FW | |

| 2010–11 | FW | |

| 2011–12 | DF | |

| 2012–13 | GK | |

| 2013–14 | FW | |

| 2014–15 | MF | |

| 2015–16 | MF | |

| 2016–17 | GK | |

| 2017–18 | GK | |

| 2018–19 | MF |

Managers

The following table contains the managers who have all won at least one (major or minor) trophy when in charge of Burnley.[138][100][114]

In bold = Major honour

| Name | Nationality | From | To | Played | Won | Drew | Lost | Win%[nb 1] | Honours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harry Bradshaw | 1896 | 1899 | 108 | 46 | 27 | 35 | 42.59 | Football League Second Division champions: 1897–98 | |

| John Haworth | July 1910 | December 1924 | 464 | 203 | 106 | 155 | 43.75 | FA Cup winners: 1913–14 Football League First Division champions: 1920–21 | |

| Harry Potts | February 1958 | February 1970 | 605 | 272 | 141 | 192 | 44.96 | Football League First Division champions: 1959–60 FA Charity Shield winners (shared): 1960 | |

| Jimmy Adamson | February 1970 | January 1976 | 272 | 104 | 74 | 94 | 38.24 | Football League Second Division champions: 1972–73 FA Charity Shield winners: 1973 | |

| Harry Potts (2) | February 1977 | October 1979 | 123 | 42 | 32 | 49 | 34.15 | Anglo–Scottish Cup winners: 1978–79 | |

| Brian Miller | October 1979 | January 1983 | 166 | 57 | 50 | 59 | 34.34 | Football League Third Division champions: 1981–82 | |

| Jimmy Mullen | October 1991 | February 1996 | 249 | 97 | 67 | 85 | 38.96 | Football League Fourth Division champions: 1991–92 Football League Second Division play–off winners: 1993–94 | |

| Owen Coyle | November 2007 | January 2010 | 116 | 49 | 29 | 38 | 42.24 | Football League Championship play–off winners: 2008–09 | |

| Sean Dyche | October 2012 | 338 | 128 | 91 | 119 | 37.87 | Football League Championship champions: 2015–16 |

Management

Football management

|

Board of directors

|

Owners

Chairman Mike Garlick holds 49.24% of outstanding shares of Burnley F.C. and member of the board of directors John Banaszkiewicz another 28.2%. The other five members of the board hold, between them, a total of 16.36%. The total holding of shares by all board members amounts to 93.8%.[139]

Burnley is one of the few clubs in the top two tiers which is British-owned. Every director at the club is locally born or based, a Claret supporter and receives no wages. As of 2019–20, Burnley is debt-free.[140]

Club identity

Kits and colours

In the early years, various designs and colours were used by Burnley. Throughout the first nine years these were various permutations of blue and white, the colours of the club's forerunners Burnley Rovers Rugby Club.[3] After two years of claret and amber stripes with black shorts, for much of the 1890s a combination of black with yellow stripes was used, although Burnley wore a shirt with pink and white stripes during the 1894–95 season. Between 1897 and 1900 the club used a plain red shirt and from 1900 until 1910 it changed to an all green shirt with white shorts. In 1910, Burnley changed the colours to claret and sky blue, the colours that it now has had for the majority of the history, save for a spell in white shirts and black shorts during the 1930s.[141] The adoption of the claret and sky blue colour combination was a homage to league champions Aston Villa, who wore those colours. The Burnley committee and manager John Haworth believed it might bring a change of fortune.[25] Burnley's away kit for the 2006–07 season, a yellow shirt with claret bar, yellow shorts and yellow socks, won the "Best Kit Design" award at the Football League Awards.[142]

Since 2019, Burnley's kits have been manufactured by Umbro, who also were the club's first shirt manufacturers from 1975 to 1981.[141] Previous manufacturers include Spall (1981–87, 1988–89), En-s (1987–88), Ellgren (1989–91), Ribero (1991–93), Mitre (1993–96), Adidas (1996–99), Super League (1999–2002), TFG Sports (2002–05), Erreà (2005–10) and Puma (2010–19).[141] The clubs' shirts are currently sponsored by LoveBet.[143] Previous shirt sponsors include POCO (1982–83), TSB (1983–84), Multipart (1984–88), Endsleigh (1988–98), P3 Computers (1998–2000), Lanway (2001–04), Hunters (2004–07), Holland's (2007–09), Cooke (2009–10), Fun88 (2010–12, 2014–15), Premier Range (2012–14), Oak Furniture Land (2015–16), Dafabet (2016–18) and LaBa360 (2018–19).[141]

Crest

The Clarets' first recorded usage of a crest was on 17 December 1887, when the club wore the Royal Arms on the shirt.[141] The Prince of Wales, Prince Albert Victor, visited Turf Moor a year before when Burnley was playing Bolton Wanderers, which was the first ever visit to a professional football ground by a member of the Royal Family.[10] Afterwards, Burnley was presented a set of white jerseys featuring a blue sash and embellished with the Royal Arms to commemorate the visit, making the Clarets the first ever club to have the right to wear it on the shirts.[144] The club would regularly wear the royal crest until 1895, when it disappeared from the shirts.[145] When Burnley played the 1914 FA Cup Final and King George V was in attendance, the Royal Arms featured once again on the claret and blue shirts.[146]

From 1914 Burnley played again in unadorned shirts, albeit the coat of arms of the town of Burnley was worn in the FA Cup semi-final in 1935 and the 1947 FA Cup Final. In 1960, when Burnley won the First Division for a second time, it was allowed to wear the town's crest on the shirts for an indefinite period of time.[144] The town's coat of arms was worn until 1969, when it was replaced with the simple vertical initials "BFC". In 1975, the initials were placed horizontally and were lettered with gold. Four years after that, in 1979, the club used a new designed badge based on the town's crest, before returning to a horizontal version of the "BFC" initials in 1983, which were lettered in white this time.[141] In the 1987–88 season Burnley returned to the former designed crest of 1979.[141]

The latest major change to Burnley's crest came in the 2009–10 season. To mark Burnley's first ever season in the Premier League, since the rebranding of the First Division in 1992, and to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 1959–60 First Division league title win, Burnley decided to return to the crest used from 1960 to 1969.[141] The following season, the town's Latin motto "Pretiumque et Causa Laboris" (English translation: "The prize and the cause of [our] labour") was replaced with the inscription "Burnley Football Club".[147]

Burnley's current badge is based on the town's coat of arms and many components of the badge — depicting cotton, history, industry, royalty — refer to the history of the club, the town of Burnley and surrounding areas.[147] The stork at the top of the badge is a reference to the Starkie family, who were prominent in the rural area of Burnley until the 20th century.[148] In its mouth it holds the Lacy knot, the badge of the de Lacy family, who held Burnley and Blackburnshire in medieval times.[148] The stork is standing on a hill (the Pennines) and cotton plants — which represents the cotton making heritage of the town.[147] In the black band, the hand represents the hand of friendship and the town of Burnley's motto, "Held to the Truth", derived from the Towneley family.[132] The two bees refer to the town's "busy ambience" and the saying "as busy as a bee", but also allude to the old Bee Hole End (currently the Jimmy McIlroy Stand) at Turf Moor.[149] Beneath, the wavy, claret-coloured line refers to the River Brun, which runs through the town.[148] The English Lion represents England and refers to the visit of Prince Albert Victor in 1886.[132]

Stadium

Burnley has played its home games at Turf Moor since February 1883, after playing at its original premises at Calder Vale for nine months. The Turf Moor site was first used for sport in 1833, when Burnley Cricket Club was established. In early 1883, they invited Burnley Football Club to move to a pitch adjacent to the cricket field.[150] Turf Moor is the longest continuously used ground of any of the 49 teams which have played in the Premier League and the second oldest continually used site for professional league football in the world, behind Preston North End's Deepdale.[5] The stadium is located on Harry Potts Way, named in honour of the club's longest serving manager.[57]

In 1888, the first Football League match at Turf Moor was an encounter against Bolton Wanderers, with Burnley emerging as 4–1 winners, Fred Poland scoring the first competitive league goal at the stadium.[151] In 1922, the ground hosted its only FA Cup semi-final to date, between Huddersfield Town and Notts County, and five years later it hosted its only senior international match, between England and Wales for the British Home Championship.[150]

The ground originally consisted of just a pitch and the first grandstand was not built until 1885.[152] At the time of the First World War, under chairman Harry Windle, the stadium's capacity was increased from 20,000 to 50,000, partly funded by the club's FA Cup win in 1914.[153] It now consists of four stands, the James Hargreaves Stand ("The Longside"), the Jimmy McIlroy Stand ("Bee Hole End"), the Bob Lord Stand and the Cricket Field Stand for home and away fans. The current capacity is 21,944 all-seated.[154] From the end of the Second World War until the mid-1960s, crowds in the stadium averaged in the 20,000–35,000 range, and Burnley averaged a club-record attendance of 33,621 in 1947–48.[155] The record attendance for a single match was already set in 1924 against Huddersfield Town in an FA Cup tie, when 54,755 spectators attended.[150] On 23 February 1960, in a fifth round FA Cup replay against Bradford City, there was an official reported attendance of 52,850 at the Turf. Some of the gates were, however, broken down and many uncounted fans poured into the ground. Many supporters were also locked out, and the road from Bradford over the Moss at Colne had to be closed to traffic.[156]

Until 1974, The Turf had a slight slope in the field, when chairman Lord made a resolution to relay the pitch and to remove the slope.[150] During the 1990s, the ground underwent further refurbishment when The Longside and Bee Hole End terraces were replaced by all-seater stands as a result of the Taylor Report, reducing the capacity to 20,900.[157] In 2019, two corner stands for disabled supporters were built (between the Jimmy McIlroy stand and both the James Hargreaves and Bob Lord stands) to meet the Accessible Stadium Guide (ASG) regulations.[158]

Supporters and rivalries

Supporters

With many other Football League clubs in the North West, supporters of Burnley are mainly drawn from East Lancashire and the western part of West Yorkshire.[159] Burnley is, however, one of the best supported clubs in English football per head of population, with average attendances of 20,000 in the Premier League in a town of approximately 73,000 inhabitants.[155][160] In 1959–60, when the club won the First Division, the fan-ratio of Burnley was twice the top flight average, as Turf Moor had an average home attendance of 26,978 and the town counted about 80,000 residents; a ratio of about 34 per cent.[46] Although as well as having a loyal, local fan base, the Clarets also have numerous supporters' clubs across the United Kingdom[161] and overseas, with supporters' clubs in Australia, Canada, Finland, Nigeria, Poland, Republic of Ireland, Spain, Thailand, and United States amongst others.[162] The club is still popular to the older generation of the African island of Mauritius, since Burnley played a few games in Mauritius and Madagascar as part of an Indian Ocean tour in 1954.[163] Burnley has a long-standing supporters' friendship with Dutch club Helmond Sport since 1997. Burnley and Helmond have a small following who regularly make an overseas journey to visit each other's matches.[164] A frequently sung chant by Burnley supporters since the early 1970s is "No Nay Never", an adaptation of the traditional Irish song "Wild Rover", which has lyrics to offend the club's main rivals Blackburn Rovers, although the song was also adapted by Blackburn supporters in the late 1970s.[165]

When falling down to the lower leagues and the simultaneously growing presence of hooliganism in English football in the 1980s, a hooligan firm linked to Burnley was established, called the "Suicide Squad", which became infamous for violently clashing with many other firms and fans in the country.[166] They also featured in the television documentary series "The Real Football Factories" presented by Danny Dyer.[167] The squad officially disbanded in 2009 after a high-profile incident with supporters of Blackburn Rovers, in which afterwards twelve members of the Suicide Squad were sentenced to jail for a total of 32 years.[168]

In 2019, Burnley fan Scott Cunliffe had been honoured by the UEFA with the #EqualGame award "for his work as role model highlighting diversity, inclusion and accessibility in football". During the 2018–19 campaign, he ran to every single away match, starting every travel at Turf Moor. It was labelled the "RunAway Challenge" and he raised more than £50,000 for Premier League clubs' community trusts and local charities in Burnley, as he covered more than 3,000 miles.[169] Notable fans over the years have included football pioneer Jimmy Hogan,[170] who was a regular attendee at Turf Moor until his death in 1974, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Edward Heath,[150] who also opened the Bob Lord Stand in 1974, and journalist Alastair Campbell,[171] who has been regularly involved in events with the club.

Since the First World War, Burnley's "unofficial match day drink" has been "Bene 'n' Hot" — the French liqueur Bénédictine topped up with hot water.[172] This is as a result of Great War soldiers of the East Lancashire Regiment acquiring a taste for the drink whilst stationed in France during the War. The soldiers drank it with hot water to keep warm in the trenches and the surviving soldiers returned to the East Lancashire area with the liqueur.[172] In excess of 30 bottles are sold at each home game, making the club one of the world's biggest sellers of the liqueur, and Turf Moor is the only British football ground to sell the liqueur.[173]

Rivalries

Traditionally, Burnley's main rivals are Blackburn Rovers, with whom it contests the East Lancashire Derby, named after the region both clubs hail from.[174][175] Games between these clubs from former mill towns are also known under the name "Cotton Mills derby", although not as common.[175] It is known as one of the longest standing derbies in world football, as both clubs are founder members of the Football League and have won the First Division and the FA Cup.[174] The two clubs are separated by 14 miles (22.5 kilometres) and besides the geographical proximity,[175] the clubs have a long-standing history of fierce rivalry too; the first competitive clash being a Football League match in 1888, in the inaugural season of the competition.[176] Four years earlier, however, they had met for the first time, although in a pre-league friendly, with considerable pride at stake.[177] Including the pre-league matches, there have been 115 matches played between both, with Burnley having the slightly better head-to-head record of the two teams, the Clarets winning 49 games and Blackburn 45.[176][177] Burnley's closest geographic rival is actually Accrington Stanley but, as they have never competed at the same level (although defunct club Accrington did), there is no significant rivalry between both.[178]

Other rivalries exist with local clubs Blackpool, Bolton Wanderers and Preston North End.[178] Burnley has regularly played them in the league and cup competitions and the encounter between Burnley and Preston is, as of 2019–20, the most frequently played match in both club's histories.[179] When in the same tier, Burnley stages a Roses rivalry with nearby West Yorkshire clubs Bradford City and Leeds United.[180][181] The Clarets also contested heated matches with Halifax Town, Plymouth Argyle, Rochdale and Stockport County in the 1990s, when Burnley was playing in the lower leagues, although feelings of animosity were mainly one-sided.[180]

Honours and achievements

League

Burnley is one of only five teams (and was the second) to have won all top four professional divisions of English football, along with Wolverhampton Wanderers, Preston North End, Sheffield United and Portsmouth.[85] The club's honours include the following:[182][183]

First Division/Premier League (Tier 1)[nb 2]

- Winners (2): 1920–21, 1959–60

- Runners–up (2): 1919–20, 1961–62

Second Division/First Division/Championship (Tier 2)

- Winners (3): 1897–98, 1972–73, 2015–16

- Promoted (3): 1912–13, 1946–47, 2013–14

- Play–off winners (1): 2008–09

Third Division/Second Division/League One (Tier 3)

- Winners (1): 1981–82

- Promoted (1): 1999–2000

- Play–off winners (1): 1993–94

Fourth Division/Third Division/League Two (Tier 4)

- Winners (1): 1991–92

Cup

- Winners (1): 1913–14

- Runners–up (2): 1946–47, 1961–62

FA Charity Shield

- Winners (2): 1960 (shared), 1973

- Runners–up (1): 1921

Texaco Cup

- Runners–up (1): 1973–74

Anglo-Scottish Cup

- Winners (1): 1978–79

EFL Trophy

- Runners–up (1): 1987–88

Regional

Lancashire Senior Cup (nowadays for reserve teams)[184]

- Winners (12): 1889–90, 1914–15, 1949–50, 1951–52, 1959–60, 1960–61, 1961–62, 1964–65, 1965–66, 1969–70, 1971–72, 1992–93

Burnley in Europe

The club has participated on three occasions in European cup competitions, excluding the Texaco Cup and the Anglo-Scottish Cup.[185][186] As a result of winning the 1959–60 First Division title, Burnley entered the 1960–61 European Cup, reaching the quarter-final stages, where it lost 5–4 on aggregate to Hamburger SV.[58] Burnley's second appearance was in the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup in the 1966–67 season, where the club again reached the quarter-finals.[186] The Clarets' most recent European campaign was in the 2018–19 UEFA Europa League, where it was eliminated in the play-off round.[121]

Records

The record for the most appearances in all competitions for Burnley is held by goalkeeper and one-club man Jerry Dawson, having made 569 first team appearances between 1907 and 1928.[187] The club's top goal scorer is George Beel, who scored 187 goals from 1923 to 1932. He also holds the record for the most league goals scored in a season, 35 in the 1927–28 season in the First Division.[188] Bert Freeman has scored the most goals in all official, competitive competitions in a single season, scoring 36 goals in the Second Division and FA Cup in 1912–13. Jimmy McIlroy is the most capped player while playing at Burnley, making 51 appearances for Northern Ireland between 1951 and 1962.[188] The first Burnley player to be capped was forward John Yates, who took to the field for England against Ireland at Anfield on 2 March 1889. He scored a hat-trick, but despite this, he was never called up again.[189]

The club's largest win in league football was a 9–0 victory over Darwen in the First Division in 1891–92. Burnley's largest victories in the FA Cup have been 9–0 wins over Crystal Palace (1908–09), New Brighton (1956–57) and Penrith (1984–85).[190] The club's record defeat is an 11–0 loss to Darwen Old Wanderers in the FA Cup first round in the 1885–86 season.[190]

Burnley's record home attendance is 54,775 for a third round FA Cup match against Huddersfield Town on 23 February 1924.[150] With the introduction of regulations enforcing all-seater stadiums, it is unlikely that this record will be beaten in the foreseeable future. The club's longest ever unbeaten run in the league was between 6 September 1920 and 25 March 1921, to which it remained unbeaten for 30 games on their way to the First Division title. It stood as the longest stretch without defeat in a single season in Football League history until Arsenal bettered it in 2003–04.[31]

The highest transfer fee received for a Burnley player is £25 million, from Everton for defender Michael Keane in July 2017,[191] while the highest transfer fee paid by the club was both for forward Chris Wood from Leeds United in August 2017 and for defender Ben Gibson from Middlesbrough in August 2018, the pair were reported to be bought for a fee of £15 million each.[192] When forward Bob Kelly moved from Burnley to Sunderland for £6,550 in 1925, he broke the world transfer record.[193]

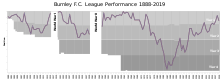

Overall league history

As of the 2019–20 season, Burnley has played 121 seasons in English league football. 57 of these have been spent in the first tier (most recently in 2019–20), 46 in the second (most recently in 2015–16), eleven in the third (most recently in 1999–2000) and seven in the fourth (most recently in 1991–92).[155]

In media and popular culture

A number of films and television programmes have included references to Burnley over the past few decades. The club's supporters briefly appear in the 1965 Beatles feature film "Help!", where footage of a crowd scene from the 1962 FA Cup Final against Tottenham is used.[132] The music video of the single "Kicker Conspiracy" from post-punk band The Fall was shot at Turf Moor in 1983.[194] Scottish actor Colin Buchanan occasionally wore a Burnley shirt on the comedy drama series "All Quiet on the Preston Front", despite being a Birmingham City supporter.[195] Burnley fan Richard Moore, who had a role in the soap opera "Emmerdale" from 2002 to 2005, regularly sneaked his Burnley paraphernalia on set. His Burnley scarf made regular appearances on the series.[196]

In 2002, the club's mascot, "Bertie Bee", became nationwide known for rugby tackling a streaker on the pitch at Turf Moor who had evaded the stewards during a match against local rivals Preston North End, and appeared on the BBC Television sporting panel show "They Think It's All Over" after the event.[197]

Burnley is referenced in "The Inbetweeners Movie" from 2011, when the main characters share a bus with a group of noisy Burnley fans, much to the distaste of one of the main characters, who stated in the scene that he dislikes the club.[198] Burnley is occasionally referred to in the series "Coronation Street", and in 2012, one of the actresses wore the club's strip in an episode, after Burnley received a request from the series to provide a kit.[199]

When the BBC highlights programme "Match of the Day" began in 1964, Bob Lord banned the BBC from televising matches at Turf Moor, and maintained the ban for five years, arguing that live coverage would "damage and undermine attendances".[200]

See also

- Burnley F.C. Women — women's only football club, affiliated with Burnley Football Club.

- UCFB — higher education institution which has its origins at Turf Moor.

Footnotes

- Win% is rounded to two decimal places.

- Upon its formation in 1992, the Premier League became the top tier of English football; the Football League First and Second Divisions then became the second and third tiers, respectively. From 2004, the First Division became the Championship and the Second Division became League One.

Sources

References

- Bird, Philip (2018). Burnley FC On This Day: History, Facts & Figures from Every Day of the Year. Pitch Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1785314254.

- "On This Day: May 18". Burnley Football Club. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "On This Day: 10th August". Burnley Football Club. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Wiseman, David (2009). The Burnley FC Miscellany. DB Publishing. ISBN 9781780911045.

- Geldard, Suzanne (27 November 2009). "Burnley chairman: I'd love to buy back the Turf Moor". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Simpson, Ray (5 December 2017). "The Story Of The Dr Dean Trophy". Burnley Football Club. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Scholes, Tony (12 June 2013). "1880–1890 Burnley Football Club are born". Clarets Mad. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Butler, Bryon (1991). The Official History of The Football Association. London: Queen Anne Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-356-19145-1.

- Smith (2014), p. 3

- Fiszman, Marc; Peters, Mark (2005). Kick Off Championship 2005–06. London: Sidan Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781903073322.

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (20 July 1999). "England 1888–89". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- When Saturday Comes (2006). When Saturday Comes: The Half Decent Football Book. Penguin. p. 134. ISBN 978-0141015569.

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (20 July 1999). "England 1889/90". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Simpson (2007), pp. 34–37

- Beraldi, Mariano; Osburg, Wolf-Rüdiger (2018). Die Weltgeschichte des Fußballs in Spitznamen: Von den Anfängen bis zum Fliegenden Holländer (in German). Hamburg: Osburg Verlag. ISBN 9783955101619.

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (27 October 1999). "England 1897/98". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Ward, Andrew (2016). Football's Strangest Matches: Extraordinary but True Stories from Over a Century of Football. Portico. ISBN 9781910232866.

- Inglis, Simon (1988). League Football and the Men Who Made It. Willow Books. p. 107. ISBN 0-00-218242-4.

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (27 October 1999). "England 1898/99". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Dart, James; Bandini, Paolo (9 August 2006). "The earliest recorded case of match-fixing". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Smith (2014), p. 4

- Smith (2014), pp. 3–5

- Smith (2014), pp. 20–27

- Smith (2014), p. 34

- "On This Day: 13 July". Burnley Football Club. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (21 January 2000). "England 1911/12". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Smith (2014), pp. 241–310

- Smith (2014), p. 260

- Smith (2014), p. 343

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (21 September 2000). "England 1920–21". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Smith (2014), p. 309

- Smith (2014), pp. 329–331

- Prosser, Mike (2019). Goalscoring Legends of Burnley. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-1698973791.

- Felton, Paul; Spencer, Barry (31 October 2013). "England 1929/30". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Ponting, Ivan (7 November 1996). "Obituary: Tommy Lawton". The Independent. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Felton, Paul. "Season 1946–47". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Thomas, Dave (2014). Who Says Football Doesn't Do Fairytales?: How Burnley Defied the Odds to Join the Elite. Pitch Publishing Ltd. p. 25. ISBN 978-1909626690.

- Kayley, Jason (25 May 2007). "No 17: 1947 FA Cup final". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Felton, Paul. "Season 1947–48". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Hopcraft, Arthur (2013). The Football Man: People & Passions in Soccer. Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1781311516.

- Godfrey, Mark (20 December 2015). "The Khrushchev of Burnley". The Football Pink. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Jensen, Neil (9 August 2013). "Great Reputations: Burnley 1959–60 – a good year for claret". Game of the People. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Smith, Mike; Thomas, Dave (2019). Bob Lord of Burnley: The Biography of Football's Most Controversial Chairman. Pitch Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1785315077.

- Ponting, Ivan (12 March 1996). "Alan Brown". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- York, Gary (24 May 2007). "John Connelly life story: Part 1". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Quelch, Tim (2015). Never Had it So Good: Burnley's Incredible 1959/60 League Title Triumph. Pitch Publishing. ISBN 9781848186002.

- "Midweek Clarets' Legends - This Week it's Harry Potts". sport.co.uk. 30 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Jack Hixon". The Independent. 24 December 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Wilson, Jonathan (27 May 2017). "How old-fashioned shadow play has helped Antonio Conte light up Chelsea". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Bishop, Paul (15 August 2014). "Instant replay: FA Cup marathon for Chelsea and Burnley". Get West London. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Turner, Georgina (24 September 2013). "Was Jesse Lingard's debut for Birmingham the most prolific ever? | The Knowledge". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Burnley v New Brighton, 26 January 1957". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- McParlan, Paul (27 February 2018). "Burnley, Total Football and the pioneering title win of 1959/60". These Football Times. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Ponting, Ivan (22 January 1996). "Obituary: Harry Potts". The Independent. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Marshall, Tyrone (20 June 2016). "'We weren't jumping around, we'd only won the league' – Burnley legend on the day the Clarets were crowned Kings of England". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), p. 14

- Posnanski, Joe (14 October 2014). "David and Goliath and Burnley". NBC SportsWorld. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Ross, James M. (16 July 2015). "European Competitions 1960–61". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Burnley match record: 1962". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Veevers, Nicholas (5 January 2015). "Robson recalls historic Cup Final goal and Spurs rivalry". The Football Association. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "Burnley legend Jimmy Adamson dies at 82". BBC Sport. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "International Honours Board Update". Burnley Football Club. 26 May 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Shaw, Phil (18 January 2016). "EFL Official Website Fifty-five years to the day: £20 maximum wage cap abolished by Football League clubs". English Football League. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Ross, James M. (20 June 2019). "English League Leading Goalscorers". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Burnley v Eintracht Frankfurt, 18 April 1967". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Ponting, Ivan (10 November 2011). "Jimmy Adamson: Footballer and manager who led Burnley to their greatest successes". The Independent. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Ross, James M. (5 August 2019). "England – List of FA Charity/Community Shield Matches". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Struthers, Greg (2 May 2004). "Caught in Time: Burnley return to the First Division, 1973 74". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0956-1382. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Cup magic back in Wimbledon". BBC Sport. 7 November 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), pp. 17–19

- Quelch (2017), p. 20

- Glanville, Brian (17 May 2007). "Obituary: Brian Miller". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "1981–82 Season Final Football Tables". English Football Archive. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Milk Cup 1982/83". Soccerbase. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Burnley Manager History | Past & Present". Soccerbase. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), pp. 24–39

- Quelch (2017), pp. 54–74

- Belam, Martin (24 April 2017). "So you've been relegated from League Two. What happens next?". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Whalley, Mike (May 2008). "The Colne Dynamoes debacle". When Saturday Comes. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), p. 62

- Quelch (2017), p. 63

- "The match that lasted a lifetime". Burnley Express. 12 September 2003. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Donlan, Matt (18 December 2009). "Sherpa final a turning point in Burnley's history". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Quelch (2017), pp. 104–106

- Tyler, Martin (9 May 2017). "Martin Tyler's stats: Most own goals, fewest different scorers in a season". Sky Sports. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Metcalf, Rupert (30 May 1994). "Football Play-Offs: County fall short as Burnley go up: Parkinson makes the difference". The Independent. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Quelch (2017), p. 160

- Walker, Michael (29 December 2001). "The Saturday Interview: Ternent close to matching the great Clarets". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Jones, Ed (7 May 2000). "Clarets steal the big prize". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Quelch (2017), p. 198

- "Burnley throw out ITV cameras". The Telegraph. 12 August 2002. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Fan Pike to probe crisis in football". Lancashire Telegraph. 25 April 2003. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Clarets manager booted out". Lancashire Telegraph. 4 May 2004. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Cotterill lands Burnley job". The Guardian. 3 June 2004. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Geldard, Suzanne (29 June 2014). "Ade Akinbiyi: Coyle was able to lift everyone when he took the Clarets up". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "2006/2007 Season". Sky Sports. 24 March 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Burnley announce appointment of Owen Coyle as their new manager". The Guardian. 22 November 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Lomax, Andrew (3 May 2009). "Owen Coyle insists Burnley are hitting form at the right time". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Herman, Martyn (25 May 2009). "Burnley promoted to Premier League". Reuters. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "Burnley 1–0 Sheff Utd". BBC Sport. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Cross, Jeremy (3 December 2008). "Carling Cup: Arsene Wenger fumes as Burnley turf out Arsenal". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Sheen, Tom (28 January 2015). "Do away goals count in the Capital One Cup semi-final?". The Independent. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Burnley 3–2 Tottenham (agg 4–6)". BBC Sport. 21 January 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Smith, Rory (9 August 2017). "When the Premier League Puts Your Town on the Map". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Bournemouth: The minnows who made the Premier League". BBC Sport. 28 April 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Coyle Hails Best Win Yet". Burnley Football Club. 6 October 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Lovejoy, Joe (25 April 2010). "Liverpool seal Burnley's relegation on back of Steven Gerrard double". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "Howe confirmed as Burnley manager". BBC Sport. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Eddie Howe: Bournemouth agree deal with Burnley for manager". BBC Sport. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Burnley: Sean Dyche named as new manager at Turf Moor". BBC Sport. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Sean Dyche's five years at Burnley". Sky Sports. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Danny Ings agrees move to Liverpool". Burnley Express. 8 June 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Burnley 2–0 Wigan Athletic". BBC Sport. 21 April 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Marshall, Tyrone (7 May 2016). "'It means a lot' - Sean Dyche hails Burnley's title triumph after Charlton victory". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Black, Dan (22 November 2019). "Burnley skipper wary of the threat former team-mate Andre Gray carries". Burnley Express. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Marshall, Tyrone (14 May 2017). "Burnley's safety is confirmed as Hull City lose at Crystal Palace". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Whalley, Mike (5 August 2017). "Sean Dyche has new grounds for optimism as Burnley spend £10.5m on training facility". The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Marshall, Tyrone (24 March 2017). "Training ground move a sign of our ambition, says Burnley captain Tom Heaton as Clarets move into their new home". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "Chelsea 2–3 Burnley". BBC Sport. 12 August 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Burnley secure European football for first time in 51 years". BBC Sport. 5 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- "Burnley 1–1 Olympiakos (2–4 on agg)". BBC Sport. 30 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "First team". Burnley Football Club. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Mee Confirmed as Captain". Burnley Football Club. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Lynch, Tony (1995). The Official P.F.A. Footballers Heroes. London: Random House. p. 140. ISBN 9780091791353.

- "Burnley – 29 Players (91 Caps)". englandstats.com. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "About the Football Hall Of Fame". National Football Museum. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Legends list in full". BBC News. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Smith, Martin (19 December 2007). "Best footballers: Shearer a hero on two fronts". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Gee, Chris (30 January 2017). "Greatest Burnley FC players honoured at Turf Moor". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Full Complement Of Heroes At Turf Moor". Burnley Football Club. 14 November 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Scholes, Tony (24 January 2017). "Our Turf Moor Heroes Launches". UpTheClarets. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Clayton, David (2014). Burnley FC Miscellany: Everything you ever needed to know about The Clarets. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445642239.

- "Boyd Named Supporters Clubs' Player Of The Year". Burnley Football Club. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Barton Crowned Player of the Year". Burnley Football Club. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Tom Heaton". Burnley Football Club. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Double Delight For Award Winner Pope". Burnley Football Club. 7 May 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Double Top For Westwood". Burnley Football Club. 5 May 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "The Managers". Burnley Football Club. 13 February 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Board of Directors". Burnley Football Club. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Conn, David (22 May 2019). "Premier League finances: the full club-by-club breakdown and verdict". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Burnley". Historical Football Kits. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Geldard, Suzanne (6 March 2007). "Clarets win kit award". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "It's A LoveBet Story For Clarets". Burnley Football Club. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "Ask Clarets Mad Answers 7". Clarets Mad. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Smith (2014), p. 243

- Smith (2014), p. 257

- Thomas, Andi (16 January 2015). "Burnley's badge is the best in the Premier League". SBNation.com. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "Burnley". The Beautiful History. 27 September 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Cowdock, Matt (22 August 2016). "Badge of the Week: Burnley FC". Box To Box Football. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "The Turf Moor Story". Burnley Football Club. 9 March 2008. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Metcalf, Mark (2013). The Origins of the Football League: The First Season 1888/89. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1445618814.

- "Turf Moor". Football Stadiums. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Smith (2014), pp. 328–329

- "Turf Moor". Premier League. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- "EFS English Clubs". European Football Statistics. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "1959/60 Series: Bradford City (FA Cup) (H)". The Longside. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Quelch (2017), p. 107

- "Disabled Supporters". Burnley Football Club. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Mellor, Gavin (2003). "Professional Football and its Supporters in Lancashire, circa 1946–1985" (PDF). Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Johnson, William (27 December 2001). "Burnley's head for heights". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Supporters Clubs". Burnley Football Club. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Club Finder". www.myburnleyfc.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Magill, Peter (2 April 2013). "Clarets ambassador tells of devastation in Mauritius". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Marshall, Jack (17 April 2018). "Clarets across borders: Turf Moor's Dutch tribute to Burnley expat". Burnley Express. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Barnes, Paulinus (21 October 1992). "Football: Fan's Eye view No. 10: Beating Clarets' blues: Burnley". The Independent. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Porter, Andrew (2005). Suicide Squad: The Inside Story of a Football Firm. Milo Books. ISBN 9781903854464.

- Plunkett, Susan (9 April 2019). "Former Burnley pub that featured in football hooligan documentary up for sale". Burnley Express. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Chadderton, Sam (19 January 2011). "Burnley 'Suicide Squad' hooligans jailed for 32 years over East Lancs derby clash". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "UEFA's 2019 #EqualGame Award winners – Borussia Dortmund and Burnley FC fan". UEFA. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Smith, Stratton (1963). The International Football Book for Boys No. 5. Souvenir Press. p. 34. ASIN B000KHKII2.

- "Aberdeen v Burnley: Alastair Campbell lauds Clarets' revival". BBC Sport. 26 July 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Benedictine Man of the Match". Burnley Football Club. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Deehan, John (25 September 2018). "Turf Moor only football ground in the UK to serve Bénédictine". Burnley Express. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Mitten, Andy (1 May 2005). "More Than A Game: Blackburn vs Burnley". FourFourTwo. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Croydon, Emily (30 November 2012). "Burnley v Blackburn Rovers: Is this football's most passionate derby?". BBC Sport. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Burnley football club: record v Blackburn Rovers". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "History of the Blackburn Rovers v Burnley derby: part one". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Football Rivalries: The Survey". The Daisy Cutter. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Burnley football club: record v Preston North End". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Rivalry Uncovered!" (PDF). The Football Fans Census. 3 February 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2004. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Flanagan, Chris (6 December 2010). "Leighton James: Leeds United rivalry makes it huge for Burnley". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Burnley football club honours". 11v11. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Burnley Honours". The Football Ground. Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Small, Gordon (2007). The Lancashire Cup: A Complete Record of the Lancashire FA Senior Cup 1879–80 to 2006–07. Nottingham: Tony Brown. ISBN 9781905891047.

- "Burnley". UEFA. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Haisma, Marcel; Zea, Antonio (9 January 2008). "European Champions' Cup and Fairs' Cup 1966–67". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Smith (2014), pp. 312–313

- "All Time Burnley Records & Achievements". Soccerbase. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "England Players – Jack Yates". England Football Online. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Burnley scoring and sequence records". Statto. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Boden, Chris (30 September 2017). "Keane desperate to face Clarets". Burnley Express. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Ben Gibson: Burnley sign Middlesbrough centre-back for joint club record fee". BBC Sport. 5 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- O'Brien, John (9 August 2016). "Evolution of world record transfers since 1893". Reuters. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Redhead, Steve (1997). Post-Fandom and the Millennial Blues: The Transformation of Soccer Culture. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0415115285.

- "Cast and Characters". The Preston Front Page. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Emmerdale star sneaks his Clarets scarf into show scenes". Lancashire Telegraph. 15 May 2004. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "VIDEO: Bertie Bee – how rugby tackling a streaker changed my career". Burnley Express. 15 March 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Burnley FC raise laughs at cult comedy film 'The Inbetweeners'". Burnley Express. 29 August 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Clarets strip to make an appearance in Coronation Street". Lancashire Telegraph. 6 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Allison, Lincoln (2001). Amateurism in sport: an analysis and a defence. Oxford: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7146-4969-6.

Bibliography

- Quelch, Tim (2015). Never Had It So Good: Burnley's Incredible 1959/60 League Title Triumph. Pitch Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1909626546.

- Quelch, Tim (2017). From Orient to the Emirates: The Plucky Rise of Burnley FC. Pitch Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1785313127.

- Simpson, Ray (2007). The Clarets Chronicles: The Definitive History of Burnley Football Club 1882-2007. Burnley Football Club. ISBN 978-0955746802.