Bergen

Bergen (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈbæ̀rɡn̩] (![]()

Bergen | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

| |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Bergen Location of Bergen  Bergen Bergen (Vestland)  Bergen Bergen (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 60°23′22″N 5°19′48″E | |

| Country | Norway |

| Region | Western Norway |

| County | Vestland |

| District | Midhordland |

| Municipality | Bergen |

| Established | before 1070 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Marte Mjøs Persen (Ap) |

| • Governing mayor | Roger Valhammer (Ap) |

| Area | |

| • City and municipality | 465.56 km2 (179.75 sq mi) |

| • Land | 445.64 km2 (172.06 sq mi) |

| • Water | 20.22 km2 (7.81 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 94.03 km2 (36.31 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,755 km2 (1,064 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 987 m (3,238 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City and municipality | 283,929 |

| • Metro | 420,000 (1 January 2015) |

| Demonym(s) | Bergenser/Bergensar |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 5003-5268 (P.O.box 5802-5899) |

| Area code(s) | (+47) 5556 |

| Website | www |

Bergen kommune | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

Coat of arms  Vestland within Norway | |

Bergen within Vestland | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Vestland |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-4601 |

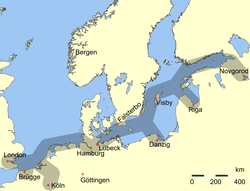

Trading in Bergen may have started as early as the 1020s. According to tradition, the city was founded in 1070 by king Olav Kyrre and was named Bjørgvin, 'the green meadow among the mountains'. It served as Norway's capital in the 13th century, and from the end of the 13th century became a bureau city of the Hanseatic League. Until 1789, Bergen enjoyed exclusive rights to mediate trade between Northern Norway and abroad and it was the largest city in Norway until the 1830s when it was overtaken by the capital, Christiania (now known as Oslo). What remains of the quays, Bryggen, is a World Heritage Site. The city was hit by numerous fires over the years. The Bergen School of Meteorology was developed at the Geophysical Institute starting in 1917, the Norwegian School of Economics was founded in 1936, and the University of Bergen in 1946. From 1831 to 1972, Bergen was its own county. In 1972 the municipality absorbed four surrounding municipalities and became a part of Hordaland county.

The city is an international center for aquaculture, shipping, the offshore petroleum industry and subsea technology, and a national centre for higher education, media, tourism and finance. Bergen Port is Norway's busiest in terms of both freight and passengers, with over 300 cruise ship calls a year bringing nearly a half a million passengers to Bergen,[2] a number that has doubled in 10 years.[3] Almost half of the passengers are German or British.[3] The city's main football team is SK Brann and a unique tradition of the city is the buekorps. Natives speak a distinct dialect, known as 'Bergensk'. The city features Bergen Airport, Flesland and Bergen Light Rail, and is the terminus of the Bergen Line. Four large bridges connect Bergen to its suburban municipalities.

Bergen has a mild winter climate, though with a lot of precipitation. From December to March, Bergen can be, in rare cases, up to 20 °C warmer than Oslo, even though both cities are at about 60° North. The Gulf Stream keeps the sea relatively warm, considering the latitude, and the mountains protect the city from cold winds from the north, north-east and east.

History

The city of Bergen was traditionally thought to have been founded by king Olav Kyrre, son of Harald Hardråde in 1070 AD,[5] four years after the Viking Age in England ended with the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Modern research has, however, discovered that a trading settlement had already been established in the 1020s or 1030s.[6]

Bergen gradually assumed the function of capital of Norway in the early 13th century, as the first city where a rudimentary central administration was established. The city's cathedral was the site of the first royal coronation in Norway in the 1150s, and continued to host royal coronations throughout the 13th century. Bergenhus fortress dates from the 1240s and guards the entrance to the harbour in Bergen. The functions of the capital city were lost to Oslo during the reign of King Haakon V (1299-1319).

In the middle of the 14th century, North German merchants, who had already been present in substantial numbers since the 13th century, founded one of the four Kontore of the Hanseatic League at Bryggen in Bergen. The principal export traded from Bergen was dried cod from the northern Norwegian coast,[7] which started around 1100. The city was granted a monopoly for trade from the north of Norway by King Håkon Håkonsson (1217-1263).[8] Stockfish was the main reason that the city became one of North Europe's largest centres for trade.[8] By the late 14th century, Bergen had established itself as the centre of the trade in Norway.[9] The Hanseatic merchants lived in their own separate quarter of the town, where Middle Low German was used, enjoying exclusive rights to trade with the northern fishermen who each summer sailed to Bergen.[10] Today, Bergen's old quayside, Bryggen, is on UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites.[11]

In 1349, the Black Death was brought to Norway by an English ship arriving in Bergen.[12] Later outbreaks occurred in 1618, 1629 and 1637, on each occasion taking about 3,000 lives.[13] In the 15th century, the city was attacked several times by the Victual Brothers,[14] and in 1429 they succeeded in burning the royal castle and much of the city. In 1665, the city's harbour was the site of the Battle of Vågen, when an English naval flotilla attacked a Dutch merchant and treasure fleet supported by the city's garrison. Accidental fires sometimes got out of control, and one in 1702 reduced most of the town to ashes.

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, Bergen remained one of the largest cities in Scandinavia, and it was Norway's biggest city until the 1830s,[15] when the capital city of Oslo became the largest. From around 1600, the Hanseatic dominance of the city's trade gradually declined in favour of Norwegian merchants (often of Hanseatic ancestry), and in the 1750s, the Hanseatic Kontor finally closed. Bergen retained its monopoly of trade with northern Norway until 1789.[16] The Bergen stock exchange, the Bergen børs, was established in 1813.

Modern history

Bergen was separated from Hordaland as a county of its own in 1831.[17] It was established as a municipality on 1 January 1838 (see formannskapsdistrikt). The rural municipality of Bergen landdistrikt was merged with Bergen on 1 January 1877.[18] The rural municipality of Årstad was merged with Bergen on 1 July 1915.

During World War II, Bergen was occupied on the first day of the German invasion on 9 April 1940, after a brief fight between German ships and the Norwegian coastal artillery. The Norwegian resistance movement groups in Bergen were Saborg, Milorg, "Theta-gruppen", Sivorg, Stein-organisasjonen and the Communist Party.[19] On 20 April 1944, during the German occupation, the Dutch cargo ship Voorbode anchored off the Bergenhus Fortress, loaded with over 120 tons of explosives, and blew up, killing at least 150 people and damaging historic buildings. The city was subject to some Allied bombing raids, aimed at German naval installations in the harbour. Some of these caused Norwegian civilian casualties numbering about 100.

Bergen is also well known in Norway for the Isdal Woman (Norwegian: Isdalskvinnen), an unidentified person who was found dead at Isdalen (“Ice Valley”) on 29 November 1970.[20] The unsolved case encouraged international speculation over the years and it remains one of the most profound mysteries in recent Norwegian history.[21][22]

The rural municipalities of Arna, Fana, Laksevåg, and Åsane were merged with Bergen on 1 January 1972. The city lost its status as a separate county on the same date,[23] and Bergen is now a municipality, in the county of Vestland.

Fires

The city's history is marked by numerous great fires. In 1198, the Bagler faction set fire to the city in connection with a battle against the Birkebeiner faction during the civil war. In 1248, Holmen and Sverresborg burned, and 11 churches were destroyed. In 1413 another fire struck the city, and 14 churches were destroyed. In 1428 the city was plundered by the Victual Brothers, and in 1455, Hanseatic merchants were responsible for burning down Munkeliv Abbey. In 1476, Bryggen burned down in a fire started by a drunk trader. In 1582, another fire hit the city centre and Strandsiden. In 1675, 105 buildings burned down in Øvregaten. In 1686 another great fire hit Strandsiden, destroying 231 city blocks and 218 boathouses. The greatest fire in history was in 1702, when 90% of the city was burned to ashes. In 1751, there was a great fire at Vågsbunnen. In 1756, yet another fire at Strandsiden burned down 1,500 buildings, and further great fires hit Strandsiden in 1771 and 1901. In 1916, 300 buildings burned down in the city centre, and in 1955 parts of Bryggen burned down.

Toponymy

Bergen is pronounced in English /ˈbɜːrɡən/ or /ˈbɛərɡən/ and in Norwegian [ˈbæ̀rɡn̩] (![]()

In 1918, there was a campaign to reintroduce the Norse form Bjørgvin as the name of the city. This was turned down - but as a compromise, the name of the diocese was changed to Bjørgvin bispedømme.[25]

Geography

Bergen occupies most of the peninsula of Bergenshalvøyen in the district of Midthordland in mid-western Hordaland. The municipality covers an area of 465 square kilometres (180 square miles). Most of the urban area is on or close to a fjord or bay, although the urban area has several mountains. The city centre is surrounded by the Seven Mountains, although there is disagreement as to which of the nine mountains constitute these. Ulriken, Fløyen, Løvstakken and Damsgårdsfjellet are always included as well as three of Lyderhorn, Sandviksfjellet, Blåmanen, Rundemanen and Kolbeinsvarden.[26] Gullfjellet is Bergen's highest mountain, at 987 metres (3,238 ft) above mean sea level.[27]

Bergen is sheltered from the North Sea by the islands Askøy, Holsnøy (the municipality of Meland) and Sotra (the municipalities of Fjell and Sund). Bergen borders the municipalities Meland, Lindås, and Osterøy to the north, Vaksdal and Samnanger to the east, Os and Austevoll to the south, and Sund, Fjell, and Askøy to the west.

Climate

Bergen has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), with plentiful rainfall in all seasons; with intermittent snowfall during winter, but the snow usually melts quickly in the city. Average annual precipitation during 1961-90 was 2,250 mm (89 in).[28] This is because Bergen is surrounded by mountains that cause moist North Atlantic air to undergo orographic lift, yielding abundant rainfall. It rained every day from 29 October 2006 to 21 January 2007: 85 consecutive days.[29] The highest temperature ever recorded was 33.4 °C (92.1 °F) on 26 July 2019,[30] beating the previous record from 2018 at 32.6 degrees, and the lowest was −16.3 °C (2.7 °F) in January 1987.[31] Bergen is considered the rainiest city in Europe, although it is not the most precipitous "place" on the continent.[32][33][34]

Bergen's weather is much warmer than the city's latitude (60.4° N) might suggest. Temperatures below -10 °C are rare. Summer temperatures sometimes reach the upper 20s, temperatures over 30 °C previously was only seen a few days each decade. The growing season in Bergen is exceptionally long for its latitude, with more than 200 days. Its mild winters move the plant hardiness zone to 8b in most coastal locations.

The high precipitation is often used in the marketing of the city, and features to a degree on postcards sold in the city. Compared to areas behind the mountains on the Scandinavian peninsula, Bergen is much wetter and has a narrower temperature range, with cool summers and mild winters. The old sunshine hours data was from the met office in the city; at this location sunlight is obscured by mountains, especially by Ulriken.[35] A new sunrecorder was established at Bergen Airport in December 2015, and this records from 1450 to 1750 (2018) hours of sunshine.

| Climate data for Bergen - Florida (met.office); average temperatures and precipitation 1981-2010; | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.9 (62.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

33.4 (92.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

11.2 (52.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7 (45) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

8.3 (47.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7 (45) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

5.4 (41.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.3 (2.7) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 252.7 (9.95) |

197.8 (7.79) |

200.3 (7.89) |

133.7 (5.26) |

104.5 (4.11) |

119.4 (4.70) |

151.1 (5.95) |

198.4 (7.81) |

254.9 (10.04) |

270.8 (10.66) |

261.4 (10.29) |

267.8 (10.54) |

2,412.8 (94.99) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19.1 | 16.4 | 17.4 | 14.0 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 15.9 | 17.0 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 18.5 | 195.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 76 |

| Source: Meteoclimat (temperatures) [36] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Bergen Airport Flesland; average temperatures and precipitation 1981-2010; sunshine 1961-1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.9 (62.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

33.4 (92.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

10.3 (50.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

7.3 (45.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.3 (39.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.3 (2.7) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 225.5 (8.88) |

169.4 (6.67) |

188.8 (7.43) |

144.5 (5.69) |

110.8 (4.36) |

111.6 (4.39) |

157.0 (6.18) |

189.7 (7.47) |

272.7 (10.74) |

257.5 (10.14) |

296.1 (11.66) |

223.9 (8.81) |

2,347.6 (92.43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19.1 | 16.4 | 17.3 | 14.0 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 15.9 | 17.0 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 18.5 | 195.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 19 | 56 | 94 | 147 | 186 | 189 | 167 | 144 | 86 | 60 | 27 | 12 | 1,187 |

| Source #1: NOAA (temperatures) [37] NOAA (humidity and sunshine)[38] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Voodoo Skies for extremes[39] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1500 | 5,500 | — |

| 1769 | 18,827 | +242.3% |

| 1855 | 37,015 | +96.6% |

| 1900 | 94,485 | +155.3% |

| 1910 | 104,224 | +10.3% |

| 1920 | 118,490 | +13.7% |

| 1930 | 129,118 | +9.0% |

| 1940 | — | |

| 1950 | 162,381 | — |

| 1960 | 185,822 | +14.4% |

| 1970 | 209,066 | +12.5% |

| 1980 | 207,674 | −0.7% |

| 1990 | 212,944 | +2.5% |

| 2000 | 229,496 | +7.8% |

| 2010 | 256,580 | +11.8% |

| 2014 | 271,949 | +6.0% |

| 2016 | 278,121 | +2.3% |

| Source: Statistics Norway.[40][41] Note: The municipalities of Arna, Fana, Laksevåg and Åsane were merged with Bergen 1 January 1972. | ||

As of the end of Q4 2019, the municipality had a population of 283,929,[1] making the population density 599 people per km2. As of 1 January 2017, the main urban area of Bergen had 254,235 residents[42] and covered an area of 96.71 square kilometres (37.34 sq mi).[43] Other urban areas, as defined by Statistics Norway, consist of Indre Arna (6,536 residents on 1 January 2012), Fanahammeren (3,690), Ytre Arna (2,626), Hylkje (2,277) and Espeland (2,182).[43]

Ethnic Norwegians make up 84.5% of Bergen's residents. In addition, 8.1% were first or second generation immigrants of Western background and 7.4% were first or second generation immigrants of non-Western background.[44] The population grew by 4,549 people in 2009, a growth rate of 1,8%. Ninety-six percent of the population lives in urban areas. As of 2002, the average gross income for men above the age of 17 is 426,000 Norwegian krone (NOK), the average gross income for women above the age of 17 is NOK 238,000, with the total average gross income being NOK 330,000.[44] In 2007, there were 104.6 men for every 100 women in the age group of 20–39.[44] 22.8% of the population were under 17 years of age, while 4.5% were 80 and above.

| Ancestry | Number |

|---|---|

| Total | 38,790 |

| 4,990 | |

| 1,840 | |

| 1,600 | |

| 1,360 | |

| 1,340 | |

| 1,330 | |

| 1,230 | |

| 1,200 | |

| 1,160 | |

| 1,110 |

The immigrant population (those with two foreign-born parents) in Bergen, includes 42,169 individuals with backgrounds from more than 200 countries representing 15.5% of the city's population (2014). Of these, 50.2% have background from Europe, 28.9% from Asia, 13.1% from Africa, 5.5% from Latin America, 1.9% from North America, and 0.4% from Oceania. The immigrant population in Bergen in the period 1993-2008 increased by 119.7%, while the ethnic Norwegian population grew by 8.1% during the same period. The national average is 138.0% and 4.2%. The immigrant population has thus accounted for 43.6% of Bergen's population growth and 60.8% of Norway's population growth during the period 1993–2008, compared with 84.5% in Oslo.[46]

The immigrant population in Bergen has changed a lot since 1970. As of 1 January 1986, there were 2,870 people with a non-Western immigrant background in Bergen. In 2006, this figure had increased to 14,630, so the non-Western immigrant population in Bergen was five times higher than in 1986. This is a slightly slower growth than the national average, which has sextupled during the same period. Also in relation to the total population in Bergen, the proportion of non-Westerns increased significantly. In 1986, the proportion of the total population in the municipality of non-Western background was 3.6%. In January 2006, people with a non-Western immigrant background accounted for 6 percent of the population in Bergen. The share of Western immigrants has remained stable at around 2% in the period. The number of Poles in Bergen rose from 697 in 2006 to 3,128 in 2010.[47]

The Church of Norway is the largest denomination in Bergen, with 201,006 (79.74%) registered adherents in 2012. Bergen is the seat of the Diocese of Bjørgvin with Bergen Cathedral as its centrepiece, while St John's Church is the city's most prominent. As of 2012, the state church is followed by 52,059 irreligious [48] 4,947 members of various Protestant free churches, 3,873 actively registrered Catholics[49][50] 2,707 registered Muslims, 816 registered Hindus, 255 registered Russian Orthodox and 147 registered Oriental Orthodox.

Cityscape

The city centre of Bergen lies in the west of the municipality, facing the fjord of Byfjorden. It is among a group of mountains known as the Seven Mountains, although the number is a matter of definition. From here, the urban area of Bergen extends to the north, west and south, and to its east is a large mountain massif. Outside the city centre and the surrounding neighbourhoods (i.e. Årstad, inner Laksevåg and Sandviken), the majority of the population lives in relatively sparsely populated residential areas built after 1950. While some are dominated by apartment buildings and modern terraced houses (e.g. Fyllingsdalen), others are dominated by single-family homes.[51]

The oldest part of Bergen is the area around the bay of Vågen in the city centre. Originally centred on the bay's eastern side, Bergen eventually expanded west and southwards. Few buildings from the oldest period remain, the most significant being St Mary's Church from the 12th century. For several hundred years, the extent of the city remained almost constant. The population was stagnant, and the city limits were narrow.[52] In 1702, seven-eighths of the city burned. Most of the old buildings of Bergen, including Bryggen (which was rebuilt in a mediaeval style), were built after the fire. The fire marked a transition from tar covered houses, as well as the remaining log houses, to painted and some brick-covered wooden buildings.[53]

The last half of the 19th century saw a period of rapid expansion and modernisation. The fire of 1855 west of Torgallmenningen led to the development of regularly sized city blocks in this area of the city centre. The city limits were expanded in 1876, and Nygård, Møhlenpris and Sandviken were urbanized with large-scale construction of city blocks housing both the poor and the wealthy.[54] Their architecture is influenced by a variety of styles; historicism, classicism and Art Nouveau.[55] The wealthy built villas between Møhlenpris and Nygård, and on the side of Mount Fløyen; these areas were also added to Bergen in 1876. Simultaneously, an urbanization process was taking place in Solheimsviken in Årstad, at that time outside the Bergen municipality, centred on the large industrial activity in the area.[56] The workers' homes in this area were poorly built, and little remains after large-scale redevelopment in the 1960s-1980s.

After Årstad became a part of Bergen in 1916, a development plan was applied to the new area. Few city blocks akin to those in Nygård and Møhlenpris were planned. Many of the worker class built their own homes, and many small, detached apartment buildings were built. After World War II, Bergen had again run short of land to build on, and, contrary to the original plans, many large apartment buildings were built in Landås in the 1950s and 1960s. Bergen acquired Fyllingsdalen from Fana municipality in 1955. Like similar areas in Oslo (e.g. Lambertseter), Fyllingsdalen was developed into a modern suburb with large apartment buildings, mid-rises, and some single-family homes, in the 1960s and 1970s. Similar developments took place beyond Bergen's city limits, for example in Loddefjord.[57]

At the same time as planned city expansion took place inside Bergen, its extra-municipal suburbs also grew rapidly. Wealthy citizens of Bergen had been living in Fana since the 19th century, but as the city expanded it became more convenient to settle in the municipality. Similar processes took place in Åsane and Laksevåg. Most of the homes in these areas are detached row houses, single family homes or small apartment buildings.[57] After the surrounding municipalities were merged with Bergen in 1972, expansion has continued in largely the same manner, although the municipality encourages condensing near commercial centres, future Bergen Light Rail stations, and elsewhere.[58][59]

As part of the modernisation wave of the 1950s and 1960s, and due to damage caused by World War II, the city government ambitiously planned redevelopment of many areas in central Bergen. The plans involved demolition of several neighbourhoods of wooden houses, namely Nordnes, Marken, and Stølen. None of the plans was carried out in its original form; the Marken and Stølen redevelopment plans were discarded and that of Nordnes only carried out in the area that had been most damaged by war. The city council of Bergen had in 1964 voted to demolish the entirety of Marken, however, the decision proved to be highly controversial and the decision was reversed in 1974. Bryggen was under threat of being wholly or partly demolished after the fire of 1955, when a large number of the buildings burned to the ground. Instead of being demolished, the remaining buildings were restored and accompanied by reconstructions of some of the burned buildings.[57]

Demolition of old buildings and occasionally whole city blocks is still taking place, the most recent major example being the 2007 razing of Jonsvollskvartalet at Nøstet.[60]

Billboards are banned in the city.[61]

Administration

Since 2000, the city of Bergen has been governed by a city government (byråd) based on the principle of parliamentarism.[62] The government consists of seven government members called commissioners, and is appointed by the city council, the supreme authority of the city. After the local elections of 2007, the city has been ruled by a right-wing coalition of the Progress Party, the Christian Democratic Party, and the Conservative Party, each with two commissioners.[63] The Conservative Party member Trude Drevland is mayor-on unpaid leave since 1 September 2015,[64][65] while conservative Ragnhild Stolt-Nielsen is the leader of the city government,[66] the most powerful political position in Bergen.

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 13 | |

| People's Action No to More Road Tolls (Folkeaksjonen nei til mer bompenger) | 11 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 3 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 7 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 14 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 2 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 3 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 4 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 6 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

In the 2015 election, the Labour Party won the Bergen election with a landslide, and got 37,8 % of the votes, up 9 percent from 2011, while the Conservative party lost 12,8 % and ended up at just 22,1 %. The Labour Party formed a new centre-left city government with the Liberal Party and the Christian Democrats. The Labour Party is now holding both the mayor office and governing mayor office. After the 2015 landslide elections for the Labour party, Marte Mjøs Persen (Labour Party) is the new Bergen mayor, and Harald Schjeldrup (Labour Party) the new Bergen governing mayor. The Labour Party has formed a new centre-left city government including the Labour Party, the Liberal Party, and the Christian Democrats.

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 28 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 6 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 4 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 15 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 6 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 6 | |

| Total number of members: | 73 | |

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 19 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 7 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 1 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 24 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 3 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 5 | |

| City Air List (Byluftlisten) | 1 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

The 2007 city council elections were held on 10 September. The Socialist Left Party (SV) and the Pensioners Party (PP) ended up as the losers of the election, SV going from 11.6% of the votes in the 2003 elections to 7.1%, and PP losing 2.9% ending up at 1.2%. The Liberal Party more than doubled, going from 2.7% to 5.8%. The Conservative Party lost 1.1% of the votes, ending up at 26.3%, while the Progress Party got 20.2% of the votes, a gain of 3% since the 2003 elections. The Christian Democratic Party gained 0.2%, ending up at 6.3%. The Red Electoral Alliance lost 1.4%, ending up at 4.5%, while the Centre Party gained 1.2%, ending up at 2.8%. Finally, the Labour Party continued being the second-largest party in the city, gaining 1% and ending up at 23.9%.[70]

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 16 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 14 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 18 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 3 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 2 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 4 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 15 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 12 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 18 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 3 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 8 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 2 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 20 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 13 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 14 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 2 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party Name (in Nynorsk) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 24 | |

| Progress Party (Framstegspartiet) | 14 | |

| Conservative Party (Høgre) | 19 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristeleg Folkeparti) | 9 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Raud Valallianse) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 3 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 6 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party Name (in Nynorsk) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 30 | |

| Progress Party (Framstegspartiet) | 10 | |

| Conservative Party (Høgre) | 16 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristeleg Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 3 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Raud Valallianse) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 4 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 10 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party Name (in Nynorsk) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 29 | |

| Progress Party (Framstegspartiet) | 17 | |

| Conservative Party (Høgre) | 22 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristeleg Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Raud Valallianse) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Joint list of the Liberal People's Party (Liberale Folkepartiet) and Liberal Party (Venstre) | 4 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party Name (in Nynorsk) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 30 | |

| Progress Party (Framstegspartiet) | 9 | |

| Conservative Party (Høgre) | 27 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristeleg Folkeparti) | 8 | |

| Liberal People's Party (Liberale Folkepartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Raud Valallianse) | 1 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party Name (in Nynorsk) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 26 | |

| Progress Party (Framstegspartiet) | 4 | |

| Conservative Party (Høgre) | 35 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristeleg Folkeparti) | 9 | |

| Liberal People's Party (Liberale Folkepartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Raud Valallianse) | 1 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 3 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 5 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

Boroughs

Bergen is divided into eight boroughs,[76] as seen on the map to the right. Clockwise, starting with the northernmost, the boroughs are Åsane, Arna, Fana, Ytrebygda, Fyllingsdalen, Laksevåg, Årstad and Bergenhus. The city centre is located in Bergenhus. Parts of Fana, Ytrebygda, Åsane and Arna are not part of the Bergen urban area, explaining why the municipality has approximately 20,000 more inhabitants than the urban area.

Local borough administrations have varied since Bergen's expansion in 1972. From 1974, each borough had a politically chosen administration. From 1989, Bergen was divided into 12 health and social districts, each locally administered. From 2000 to 2004, the former organizational form with eight politically chosen local administrations was again in use and from 2008 through to 2010, a similar form existed where the local administrations had less power than previously.[77]

| Borough | Population[78] | % | Area (km2) | % | Density (/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arna | 12,680 | 4.9 | 102.44 | 22.0 | 123 |

| Bergenhus1 | 38,544 | 14.8 | 26.58 | 5.7 | 4.415 |

| Fana | 38,317 | 14.8 | 159.70 | 34.3 | 239 |

| Fyllingsdalen | 28,844 | 11.1 | 18.84 | 4.0 | 1.530 |

| Laksevåg | 38,391 | 14.8 | 32.72 | 7.0 | 1.173 |

| Ytrebygda | 25,710 | 9.9 | 39.61 | 8.5 | 649 |

| Årstad2 | 37,614 | 14.5 | 14.78 | 3.2 | 4.440 |

| Åsane | 39,534 | 15.2 | 71.01 | 15.2 | 556 |

| Not stated | 758 | ||||

| Total | 260,392 | 100 | 465.68 | 100 | 559 |

(Pertaining to the table above: The acreage figures include fresh water and uninhabited mountain areas, except:

1 1 The borough Bergenhus is 8.73 km2 (3.37 sq mi), the rest is water and uninhabited mountain areas.

2 2 The borough Årstad is 8.47 km2 (3.27 sq mi), the rest is water and uninhabited mountain areas.)

A former borough, Sentrum

Sentrum (literally, "Centre") was a borough (with the same name as a present-day neighbourhood). The borough was numbered 01, and its perimeter was from Store Lungegårdsvann and Strømmen along Puddefjorden around Nordnes and over to Skuteviken, up Mt. Fløyen east of Langelivannet, on to Skansemyren and over Forskjønnelsen to Store Lungegårdsvann, south of the railroad tracks.[79]

The population of the (now defunct) borough, numbered in 1994 more than 18,000 people.[79]

Education

There are 64 elementary schools,[80] 18 lower secondary schools[81] and 20 upper secondary schools[82] in Bergen, as well as 11 combined elementary and lower secondary schools.[83] Bergen Cathedral School is the oldest school in Bergen and was founded by Pope Adrian IV in 1153.[84]

The "Bergen School of Meteorology" was developed at the Geophysical Institute beginning in 1917, the Norwegian School of Economics was founded in 1936, and the University of Bergen in 1946.

The University of Bergen has 16,000 students and 3,000 staff, making it the third-largest educational institution in Norway.[85] Research in Bergen dates back to activity at Bergen Museum in 1825, although the university was not founded until 1946. The university has a broad range of courses and research in academic fields and three national centres of excellence, in climate research, petroleum research and medieval studies.[86] The main campus is located in the city centre. The university co-operates with Haukeland University Hospital within medical research. The Chr. Michelsen Institute is an independent research foundation established in 1930 focusing on human rights and development issues.[87]

The Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, which has its main campus in Kronstad, has 16,000 students and 1800 staff.[88] It focuses on professional education, such as teaching, healthcare and engineering. The college was created through amalgamation in 1994; campuses are spread around town but will be co-located at Kronstad. The Norwegian School of Economics is located in outer Sandviken and is the leading business school in Norway,[89] having produced three Economy Nobel Prize laureates.[90] The school has more than 3,000 students and approximately 400 staff.[91] Other tertiary education institutions include the Bergen School of Architecture, the Bergen National Academy of the Arts, located in the city centre with 300 students,[92] and the Norwegian Naval Academy located in Laksevåg. The Norwegian Institute of Marine Research has been located in Bergen since 1900. It provides research and advice relating to ecosystems and aquaculture. It has a staff of 700 people.[93]

Economy

In August 2004, Time magazine named the city one of Europe's 14 "secret capitals"[94] where Bergen's capital reign is acknowledged within maritime businesses and activities such as aquaculture and marine research, with the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) (the second-largest oceanography research centre in Europe) as the leading institution. Bergen is the main base for the Royal Norwegian Navy (at Haakonsvern) and its international airport Flesland is the main heliport for the Norwegian North Sea oil and gas industry, from where thousands of offshore workers commute to their work places onboard oil and gas rigs and platforms.[95]

One of Norway's largest shopping centres, Lagunen Storsenter, is located in Fana in Bergen, with retail sales of 2,8 billion Norwegian kroner, and around 4.6 million visitors in 2018.[96]

Tourism is an important income source for the city. The hotels in the city may be full at times,[97][98] due to the increasing number of tourists and conferences. Prior to the Rolling Stones concert in September 2006, many hotels were already fully booked several months in advance.[99] Bergen is recognized as the unofficial capital of the region known as Western Norway, and recognized and marketed as the gateway city to the world-famous fjords of Norway, and for that reason, it has become Norway's largest - and one of Europe's largest - cruise ship ports of call.[100]

Transport

Bergen Airport, Flesland, is located 18 kilometres (11 mi) from the city centre, at Flesland.[101] In 2013, the Avinor-operated airport served 6 million passengers. The airport serves as a hub for Scandinavian Airlines, Norwegian Air Shuttle and Widerøe; there are direct flights to 20 domestic and 53 international destinations.[102] Bergen Port, operated by Bergen Port Authority, is the largest seaport in Norway.[103] In 2011, the port saw 264 cruise calls with 350,248 visitors,[104] In 2009, the port handled 56 million tonnes of cargo, making it the ninth-busiest cargo port in Europe.[105] There are plans to move the port out of the city centre, but no location has been chosen.[106] Fjord Line operates a cruiseferry service to Hirtshals, Denmark. Bergen is the southern terminus of Hurtigruten, the Coastal Express, which operates with daily services along the coast to Kirkenes.[101] Passenger catamarans run from Bergen south to Haugesund and Stavanger,[107] and north to Sognefjord and Nordfjord.[108]

The city centre is surrounded by an electronic toll collection ring using the Autopass system.[109] The main motorways consist of E39, which runs north–south through the municipality, E16, which runs eastwards, and National Road 555, which runs westwards. There are four major bridges connecting Bergen to neighbouring municipalities: the Nordhordland Bridge,[110] the Askøy Bridge,[111] the Sotra Bridge[112] and the Osterøy Bridge. Bergen connects to the island of Bjorøy via the subsea Bjorøy Tunnel.[113]

Bergen Station is the terminus of the Bergen Line, which runs 496 kilometres (308 mi) to Oslo.[114] The Norwegian State Railways operates express trains to Oslo and the Bergen Commuter Rail to Voss. Between Bergen and Arna Station, the train runs about every 30 minutes through the Ulriken Tunnel; there is no corresponding road tunnel, forcing road vehicles to travel via Åsane or Nesttun.[115]

Bergen is one of the smallest cities in Europe to have both tram and trolleybus electric urban transport systems simultaneously. Public transport in Hordaland is managed by Skyss, which operates an extensive city bus network in Bergen and to many neighbouring municipalities,[116] including one route which operates as a trolleybus. The trolleybus system in Bergen is the only one still in operation in Norway and one of two trolleybus systems in Scandinavia.[117]

The modern tram Bergen Light Rail (Bybanen) opened between the city centre and Nesttun in 2010,[118] extended to Rådal (Lagunen Storsenter) in 2013 and to the Bergen airport Flesland in 2017.[119] Extensions to other boroughs may occur later.[120] Fløibanen is a funicular which runs from the city centre to Mount Fløyen and Ulriksbanen is an aerial tramway which runs to Mount Ulriken.

Culture and sports

Bergens Tidende (BT) and Bergensavisen (BA) are the largest newspapers, with circulations of 87,076 and 30,719 in 2006,[121] BT is a regional newspaper covering all of Hordaland and Sogn og Fjordane, while BA focuses on metropolitan Bergen. Other newspapers published in Bergen include the Christian national Dagen, with a circulation of 8.936,[121] and TradeWinds, an international shipping newspaper. Local newspapers are Fanaposten for Fana, Sydvesten for Laksevåg and Fyllingsdalen and Bygdanytt for Arna and the neighbouring municipality Osterøy.[121] TV 2, Norway's largest private television company, is based in Bergen.

The 1,500-seat Grieg Hall is the city's main cultural venue,[122] and home of the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, founded in 1765,[123] and the Bergen Woodwind Quintet. The city also features Carte Blanche, the Norwegian national company of contemporary dance. The annual Bergen International Festival is the main cultural festival, which is supplemented by the Bergen International Film Festival. Two internationally renowned composers from Bergen are Edvard Grieg and Ole Bull. Grieg's home, Troldhaugen, has been converted to a museum. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Bergen produced a series of successful pop, rock and black metal artists,[124] collectively known as the Bergen Wave.[125][126]

Den Nationale Scene is Bergen's main theatre. Founded in 1850, it had Henrik Ibsen as one of its first in-house playwrights and art directors. Bergen's contemporary art scene is centred on BIT Teatergarasjen, Bergen Kunsthall, United Sardines Factory (USF) and Bergen Center for Electronic Arts (BEK). Bergen was a European Capital of Culture in 2000.[127] Buekorps is a unique feature of Bergen culture, consisting of boys aged from 7 to 21 parading with imitation weapons and snare drums.[128][129] The city's Hanseatic heritage is documented in the Hanseatic Museum located at Bryggen.[130]

SK Brann is Bergen's premier football team; founded in 1908, they have played in the (men's) Norwegian Premier League for all but seven years since 1963 and consecutively, except one season after relegation in 2014, since 1987. The team were the football champions in 1961-1962, 1963, and 2007,[131] and reached the quarter-finals of the Cup Winners' Cup in 1996-1997. Brann play their home games at the 17,824-seat Brann Stadion.[132] FK Fyllingsdalen is the city's second-best team, playing in the Second Division at Varden Amfi. Its predecessor, Fyllingen, played in the Norwegian Premier League in 1990, 1991 and 1993. Arna-Bjørnar and Sandviken play in the Women's Premier League.

Bergen IK is the premier men's ice hockey team, playing at Bergenshallen in the First Division. Tertnes play in the Women's Premier Handball League, and Fyllingen in the Men's Premier Handball League. In athletics, the city is dominated by IL Norna-Salhus, IL Gular and FIK BFG Fana, formerly also Norrøna IL and TIF Viking.

Bergensk is the native dialect of Bergen and a variation of Vestnorsk. It was strongly influenced by Low German-speaking merchants from the mid-14th to mid-18th centuries. During the Dano-Norwegian period from 1536 to 1814, Bergen was more influenced by Danish than other areas of Norway. The Danish influence removed the female grammatical gender in the 16th century, making Bergensk one of very few Norwegian dialects with only two instead of three grammatical genders. The Rs are uvular trills, as in French, which probably spread to Bergen some time in the 18th century, overtaking the alveolar trill in the time span of two to three generations. Owing to an improved literacy rate, Bergensk was influenced by riksmål and bokmål in the 19th and 20th centuries. This led to large parts of the German-inspired vocabulary disappearing and pronunciations shifting slightly towards East Norwegian.[133]

The 1986 edition of the Eurovision Song Contest took place in Bergen. Bergen was the host city for the 2017 UCI Road World Championships. The city is also a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network in the category of gastronomy since 2015.[134]

Music

Bergen has been the home of several notable alternative bands, collectively referred to as the Bergen Wave. These bands include Röyksopp and Kings of Convenience on the small, Bergen-based record label Tellé Records, as well as related side-projects, such as The Whitest Boy Alive and Kommode, on independent labels. Other internationally well-received artists also originating from Bergen include Sondre Lerche, Magnet, Kygo, Boy Pablo and Alan Walker.

Street art

Bergen is considered to be the street art capital of Norway.[135] Famed artist Banksy visited the city in 2000[136] and inspired many to start creating street art. Soon after, the city brought up the most famous street artist in Norway: Dolk.[137][138] His art can still be seen in several places in the city, and in 2009 the city council choose to preserve Dolk's work "Spray" with protective glass.[139] In 2011, Bergen council launched a plan of action for street art in Bergen from 2011 to 2015 to ensure that "Bergen will lead the fashion for street art as an expression both in Norway and Scandinavia.[140]

The Madam Felle (1831-1908) monument in Sandviken, is in honour of a Norwegian woman of German origin, who in the mid-19th century managed, against the will of the council, to maintain a counter of beer. A well-known restaurant of the same name is now situated at another location in Bergen. The monument was erected in 1990 by sculptor Kari Rolfsen, supported by an anonymous donor. Madam Felle, civil name Oline Fell, was remembered after her death in a popular song, possibly originally a folksong,[141] "Kjenner Dokker Madam Felle?" by Lothar Lindtner and Rolf Berntzen on an album in 1977.

Neighbourhoods

The traditional neighbourhoods of Bergen include Bryggen, Eidemarken, Engen, Fjellet,

Kalfaret, Ladegården, Løvstakksiden,[142] Marken, Minde,

Møhlenpris, Nordnes, Nygård, Nøstet, Sandviken,

Sentrum, Skansen, Skuteviken, Strandsiden, Stølen, Sydnes,

Verftet, Vågsbunnen, Wergeland,[143] and Ytre Sandviken.

Grunnkretser

The various addresses in Bergen, each belong to one of the various grunnkrets.

International business

Each year Bergen sells the Christmas Tree seen in Newcastle's Haymarket as a sign of the ongoing friendship between the sister cities.[144] The Nordic friendship cities of Bergen, Gothenburg, Turku and Aarhus arrange inter-Nordic camps each year by registering 10th grade school classes from each of the other cities to school camps, for a profit. Bergen received a totem pole as a gift of friendship from the city of Seattle on the city's 900th anniversary in 1970. It is now placed in the Nordnes Park and gazes out over the sea towards the friendship city far to the west.

See also

- List of people from Bergen

References

- "Table 2: Population and quarterly population changes. The whole country, counties and municipalities". Statistics Norway. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Heggemsnes, Nils (26 September 2012). "Bergen Havn". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "Cruisestatistikk". Cruise (in Norwegian). Port of Bergen. 2016. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Brekke, Nils Georg (1993). Kulturhistorisk vegbok Hordaland (in Norwegian). Bergen: Hordaland Fylkeskommune. ISBN 82-7326-026-7.

- Elisabeth Farstad (2007). "Om kommunen" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- NRK, "Bergens historie må skrives om"

- Marguerite Ragnow (2007). "Cod". Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- Tom R. Hjertholm (16 December 2013). "- Tørrfisken vender hjem". Bergensavisen.

- Alf Ragnar Nielssen (1 January 1950). "Indigenous and Early Fisheries in North-Norway" (PDF). The Sea in European History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Anette Skogseth Clausen. "7. oktober 1754 - fra et hanseatisk kontor til et norsk kontor med hanseater" (in Norwegian). Arkivverket. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- UNESCO (2007). "World Heritage List". Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- Carl Hecker, Justus Friedrich (1833). The Black Death in the Fourteenth Century.

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol III, (1847) Charles Knight, London, p.211.

- Downing Kendrick, Thomas (2004). A History of the Vikings. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-486-43396-7.

- "Innvandring 1600-2000, Arkivenes dag 2002" (in Norwegian). Arkivverket. Archived from the original on 6 December 2002. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- Ivan Kristoffersen (2003). "Historien om Norge i nord" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- "Distriktsinndeling og navn" (in Norwegian). Fornyings- og administrasjonsdepartementet. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- Statistics Norway (1999). "Historisk oversikt over endringer i kommune- og fylkesinndelingen" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- Jenny Heggsvik; Lars Borgersrud; August Rathke; Egil Christophersen; Ole-Jacob Abraham. "Prosjektbeskrivelse for det historiske forskningsprosjektet SABORG I BERGEN". Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- NRK (21 November 2017). "The Isdalen Mystery". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- McCarthy, Marit Higraff and Neil (25 June 2019). "Death in Ice Valley: New clues in a Norwegian mystery". Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Tønder, Finn Bjørn (26 November 2002). "Viktig nyhet om Isdalskvinnen" [Important news about Isdal Woman]. Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Bergen Kommune (2007). "Styringssystemet i Bergen kommune" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- Brekke, Nils Georg (1993). Kulturhistorisk vegbok Hordaland (in Norwegian). Bergen: Hordaland Fylkeskommune. p. 252. ISBN 82-7326-026-7.

- "Bjørgvin bispedøme" (in Norwegian). Scandion.no. 2004. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- Gunhild Agdesteen (2007). "I den syvende himmel". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- "Norwegian Mountains: Gullfjellstoppen". Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- Meterologisk Institutt (2007). "met.no: Normaler for Bergen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ANB-NTB (2007). "Stopp for nedbørsrekord" (in Norwegian). siste.no. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- "Nå er 33,4 den nye varmerekorden i Bergen". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Bjørbæk, G. 2003. Norsk vær i 110 år. N.W. DAMM & Sønn. ISBN 82-04-08695-4; page 260

- Meze-Hausken, Elisabeth (October 2007). "Seasons in the sun--weather and climate front-page news stories in Europe's rainiest city, Bergen, Norway". International Journal of Biometeorology. 52 (1): 17–31. Bibcode:2007IJBm...52...17M. doi:10.1007/s00484-006-0064-5. hdl:1956/2114. ISSN 1432-1254. PMID 17245564.

- "The rainiest city in Europe. Allegedly". eugene.kaspersky.com. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Europe and the United Kingdom Average Yearly Annual Precipitation". www.eldoradoweather.com. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Over 1600 soltimer i Bergen i fjor trass i elendig vær i skoleferien". 10 February 2017.

- http://meteo-climat-bzh.dyndns.org/listenormale-1981-2010-1-p159.php

- "NOAA stats - Bergen". NOAA. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "BERGEN - FLORIDA Climate Normals: 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Microsoft Word - FOB-Hefte.doc" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- "Tabell 6 Folkemengde per 1. januar, etter fylke og kommune. Registrert 2009. Framskrevet 2010-2030, alternativ MMMM" (in Norwegian). Ssb.no. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- "Population and land area in urban settlements, 1 January 2017". Statistics Norway. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- "Urban settlements. Population and area, by municipality. 1 January 2012". Statistics Norway. 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "SSB: Tall om Bergen kommune" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- "Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre i 13 kommuner, page 476" (in Norwegian). ssb.no. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- "Statistics Norway". Stat Bank. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Immigrant population in Bergen

- "County Mayor of Hordaland - Norwegian". Fylkesmannen.no. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- http://www.katolsk.no/organisasjon/norge/kommun03

- "Bergens Tidende - Norwegian". Bt.no. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. p. 27. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. p. 23. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. p. 25. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- Østerbø, Kjell (23 September 2007). "Da rike og fattige fikk sine strøk". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. pp. 25–26. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. pp. 26–27. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. pp. 9–61. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- Mæland, Pål Andreas (16 May 2008). "Nå kommer slangen til Paradis". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Røyrane, Eva (9 May 2007). "Bergen bygges tettere". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Okkenhaug, Liv Solli (21 April 2007). "Rev de siste husene". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- São Paulo: The City With No Outdoor Advertisements

- "Styringssystem" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- Christian Lura (2007). "- Fantastisk å bli spurt" (in Norwegian). Bergens Tidende. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- Vibeke Vik Nordang, Elisabeth Farstad (2007). "Har valt Gunnar Bakke til ordførar" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- Bergens-ordfører Trude Drevland ut i permisjon

- Vibeke Vik Nordang (2007). "Byrådet er valt" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- "Tall for Norge: Kommunestyrevalg 2019 - Nordland". Valg Direktoratet. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Table: 04813: Members of the local councils, by party/electoral list at the Municipal Council election (M)" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway.

- "Tall for Norge: Kommunestyrevalg 2011 - Hordaland". Valg Direktoratet. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Valgresultater - regjeringen.no" (in Norwegian). Kommunal- og regionaldepartementet. 2007. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Kommunestyrevalget 1995" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1996. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Kommunestyrevalget 1991" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1993. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Kommunestyrevalget 1987" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1988. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Kommunestyrevalget 1983" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1984. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Kommunestyrevalget 1979" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1979. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Statistics Norway (2004). "Bydeler i Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger og Trondheim" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- "Lokaldemokratiets utvikling 1814 - 2014". Bergen kommune (in Norwegian Bokmål). Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Statistics Norway - Population, by sex and age. Bergen. Urban district". Ssb.no. 1 January 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Bergen byleksikon, trykt utgave 2009 (25 January 2001). "Bergen byleksikon".

- "Oversikt over barneskoler" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Oversikt over ungdomsskoler" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Skoleportalen" (in Norwegian). Hordaland fylkeskommune. 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Oversikt over kombinerte skoler" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- Hartvedt, Gunnar Hagen (1994). Bergen Byleksikon. Kunnskapsforlaget. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- "Om Universitetet i Bergen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Mia Kolbjørnsen and Hilde Kvalvaag (2002). "UiB får tre SFF" (in Norwegian). på høyden. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- "About CMI" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- "Høgskolen på Vestlandet" (in Norwegian). 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "FT.com / Business Education / Masters in management". Financial Times (in Norwegian). 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2004". 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- "Om NHH" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- "Om Kunsthøgskolen i Bergen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- "About imr" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- "Europe's Secret Capitals". TIME Magazine. 30 August 2004. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- "Film Location:Bergen". West Norway Film Commission. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- "Olav Thon Group Annual Report 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- Lars Kvamme and Ingvild Bruaset. "Russerne kommer" (in Norwegian). bt.no. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- Frode Buanes and Lars Kvamme (2006). "Sender bergensturister vekk" (in Norwegian). bt.no. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- Arild Berg Karlsen and Erik Fossen (2006). "Fulle hoteller møter Stones-fansen" (in Norwegian). bt.no. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- Bergen Havn. "Velkommen til Bergen havn - "Inngangen til Fjordene"" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- "Transport to Bergen". Innovation Norway. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Flight Timetables". Avinor. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Eliassen, Jan I. (24 June 2006). "Bergen havn holder koken". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Cruise ships". Bergen Port Authority. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "World Port Rankings 2009" (PDF). American Association of Port Authorities. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Haga, Anders (24 June 2006). "- Vi har alle vært feige". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Hurtigbåt- og lokalbåtruter" (in Norwegian). Tide ASA. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "Fjord1 - Ekspressbåter" (in Norwegian). Fjord1. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- Gunnar Hagen Hartvedt (1994). "bompengering". Bergen Byleksikon: 119–120.

- Norwegian Public Roads Administration (1994). "The Nordhordland Bridge" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2006.

- "Askøy Bridge" (PDF). Aas-Jakobsen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Fjell, Ragnvald (1989). Sotrabrua (in Norwegian). Fjell: A/S Sotrabrua. p. 5.

- Jahnsen, Jack (2006). Fastlandssamband for Bjorøy og Tyssøy (in Norwegian). Straume: Fastlandssambandet Tyssøy - Bjorøy. ISBN 82-303-0642-7.

- Jernbaneverket (2007). Jernbanestatistikk 2006 (PDF). Oslo: Jernbaneverket. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2007.

- Aagesen, Ragnhild (21 September 2010). "Bergen-Arna" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "About Skyss". Skyss. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Aspenberg, Nils Carl (1996). Trolleybussene i Norge. Oslo: Baneforlaget. p. 96.

- "Signingsferden" (in Norwegian). 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Melhus, Ståle (11 September 2009). "Vil ha bybane til Flesland i 2015". Fanaposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Rykka, Ann Kristin and Solfrid Torvund (13 December 2006). "Usamde om bybaneutvidinga". Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (in Norwegian).

- "Avisenes leser- og opplagstall for 2006" (in Norwegian). Mediebedriftenes Landsforening. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- "Grieghallen: Floor space and capacity". Grieg Hall. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- "Bergen Filharmoniske Orkester" (in Norwegian). 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Ann Kristin Frøystad (2003). "Telle: - Angrer ingenting" (in Norwegian). ba.no. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- Lars Ursin (2005). "Bløffmakerens guide til Bergensbølgen". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Lars Ursin (2005). "Bergensbølgen tørrlagt på Alarm" (in Norwegian). Bergens Tidende. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- "European Capitals of Culture 2000-2005". Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- "What is a buekorps?". Buekorpsene.com. 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- "Studenter hestes av buekorps på nettet" (in Norwegian). Studvest.no. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- Conrad Fredrik von der Lippe (Store norske leksikon)

- Ole Ivar Store (2007). "- Gratulerer, Brann!" (in Norwegian). Norges Fotballforbund. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- "Stadionfakta" (in Norwegian). Brann.no. 2007. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- Nesse, Agnete (2003). Slik ble vi bergensere - Hanseatene og bergensdialekten. Sigma Forlag. ISBN 82-7916-028-0.

- "Bergen, City of Gastronomy - Havbyen Bergen". marin.bergen-chamber.no. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- "Gatekunstens hovedstad" (in Norwegian). Ba.no. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "Fikk Banksy-bilder som takk for overnatting" (in Norwegian). Dagbladet.no. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- "Derfor valgte ikke DOLK Bergen" (in Norwegian). Ba.no. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Populær Dolk selger så det suser" (in Norwegian). Bt.no. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- "Forsvarer verning av graffiti" (in Norwegian). Ba.no. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- "Bergenkommune.no - Graffiti og gatekunst i kulturbyen Bergen - Utredning og handlingsplan for perioden 2011-2015" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Bergen.kommune.no. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Davidsen, Knut B. (7 December 2002). "Var madam Felle Jonnemann sin mor?" [Was Madam Felle Jonnemann's Mother?]. Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian Bokmål). Bergen, Norway: Media Norge, Schibsted. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- Et liv uten filter

- Frykter spredning av narkomiljøet

- "Æresborger av Newcastle". kongehuset.no. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- "Bergen kommune - International relations - Sister Cities". 2 March 2001. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "City of Aarhus Sister cities". 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Town Twinning | Newcastle City Council". Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- "Seattle International Sister City: Bergen, Norway". Retrieved 10 August 2011.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bergen. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bergen, Norway. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bergen. |

- Municipality website in Norwegian and English

- German U-Boat Base in Bergen