Acadians

The Acadians (French: Acadiens, IPA: [akadjɛ̃]) are the descendants of French colonists who settled in Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries, many of whom are also descended from the Indigenous peoples of the region.[lower-alpha 1][4]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~126,146 – 2,000,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

96,145[1][2] 901,260 | |

| 32,950 | |

| 25,400 | |

| 20,400 | |

| 11,180 | |

| 8,745 | |

| 3,020 | |

| 30,000 | |

| 815,260 | |

| 56,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Acadian French (a variety of French with 370,000 speakers in Canada),[3] English, or both; some areas speak Chiac; those who have resettled to Quebec typically speak Quebec French or Joual. | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| French (Poitevin and Saintongeais), Cajuns, Métis, Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, Penobscot, French-Canadians | |

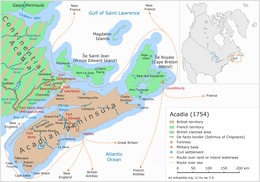

The colony was located in what is now Eastern Canada's Maritime provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island), as well as parts of Quebec, and present-day Maine to the Kennebec River, Acadia was a distinctly separate colony of New France. It was geographically and administratively separate from the French colony of Canada (modern-day Quebec). As a result, the Acadians and Québécois developed two distinct histories and cultures.[5] The settlers whose descendants became Acadians primarily came from western and southwestern regions of France, such as Poitou and Aquitaine.[6]

During the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War), British colonial officers suspected that Acadians were aligned with France, after finding some Acadians fighting alongside French troops at Fort Beauséjour. Though most Acadians remained neutral during the French and Indian War, the British, together with New England legislators and militia, carried out the Great Expulsion (Le Grand Dérangement) of the Acadians during the 1755–1764 period. They deported approximately 11,500 Acadians from the maritime region. Approximately one-third perished from disease and drowning.[7] The result was described as an ethnic cleansing of the Acadians from Maritime Canada.[8]

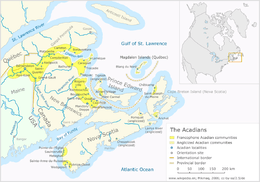

Most Acadians were deported to various British American colonies, where many were forced into servitude or marginal lifestyles. Some Acadians were deported to England, to the Caribbean, and some were deported to France. After being expelled to France, many Acadians were eventually recruited by the Spanish government to migrate to present-day Louisiana (known then as Spanish colonial Luisiana), under Spanish rule since the British victory in the Seven Years War. Their descendants gradually developed what became known as Cajun culture.[9]

In time, some Acadians returned to the Maritime provinces of Canada, mainly to New Brunswick. The British prohibited them from resettling their lands and villages in what became Nova Scotia. Before the US Revolutionary War, the Crown settled Protestant European immigrants and New England Planters in former Acadian communities and farmland. After the war, it made land grants in Nova Scotia to Loyalists (including nearly 3,000 Black Loyalists, slaves of rebels given freedom after joining British forces). British policy was to establish a majority culture of Protestant religions, and to assimilate Acadians with the local populations where they resettled.[7]

Acadians speak a variety of French called Acadian French. Many of those in the Moncton area speak Chiac and English. The Louisiana Cajun descendants speak a variety of American English called Cajun English. Many also speak Cajun French, a close relative of Acadian French from Canada, but influenced by Spanish and the West African languages of Louisiana and the peoples they mixed with.

Pre-deportation history

During the early 1600s,[10] about sixty French families were established in Acadia. They developed friendly relations with the peoples of the Wabanaki Confederacy (particularly the regional Mi'kmaq), learning their hunting and fishing techniques developed for local conditions. The Acadians lived mainly in the coastal regions of the Bay of Fundy; they reclaimed farming land from the sea through building dikes to control water and drain certain wetlands. Living in a contested borderland region between French Canada (modern Quebec) and the British territories on New England and the coast, the Acadians often became entangled in the conflict between the powers. Their competition in Europe played out in North America as well. Over a period of seventy-four years, six wars took place in Acadia and Nova Scotia, in which the Confederacy and some Acadians fought to keep the British from taking over the region (See the four French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War).

While France lost political control of Acadia in 1713, the Mí'kmaq did not concede land to the British. Along with some Acadians, the Mi'kmaq from time to time used military force to resist the British. That was particularly evident in the early 1720s during Dummer's War, but hostilities were brought to a close by a treaty signed in 1726.

The British had conquered Acadia in 1710. Over the next 45 years, the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. Many were influenced by Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre, who from his arrival in 1738 until his capture in 1755, preached against the 'English devils'.[11] Acadians took part in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[12] During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat posed by the Acadians and to interrupt the vital supply lines which they provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[13][14]

The British founded the town of Halifax and fortified it in 1749 in order to establish a base against the French. The Mi'kmaq resisted the increased number of British (Protestant) settlements by making numerous raids on Halifax, Dartmouth, Lawrencetown, and Lunenburg. During the French and Indian War, the Mi'kmaq assisted the Acadians in resisting the British during the Expulsion of the Acadians.[15]

Many Acadians might have signed an unconditional oath to the British monarchy had the circumstances been better, while other Acadians would not sign because they were anti-British. The French and British competition had a long history, including opposing Christian established religions: Catholic in France and its colonies, and Protestant (Anglican) in England.[16] Acadians had numerous reasons against signing an oath of loyalty to the British Crown. As noted, the British monarch was the head of the (Protestant) Anglican Church of England. Acadian men feared that signing the oath would commit them to fighting against France during wartime. They also worried about whether their Mi'kmaq neighbours might perceive an oath as acknowledging the British claim to Acadia rather than that of the indigenous Mi'kmaq. Acadians believed that if they signed the oath, they might put their villages at risk of attack by the Mi'kmaq.[17]

Acadians at Annapolis Royal by Samuel Scott, 1751

Acadians at Annapolis Royal by Samuel Scott, 1751 Acadians by Samuel Scott, Annapolis Royal, 1751

Acadians by Samuel Scott, Annapolis Royal, 1751 'Homme Acadien' (Acadian Man) by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur

'Homme Acadien' (Acadian Man) by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur

Deportation

In the Great Expulsion (known by French speakers as le Grand Dérangement), after the Battle of Fort Beauséjour beginning in August 1755 under Lieutenant Governor Lawrence, approximately 11,500 Acadians (three-quarters of the Acadian population in Nova Scotia) were expelled, their lands and property confiscated, and in some cases their homes burned. The Acadians were deported to separated locations throughout the British eastern seaboard colonies, from New England to Georgia. Although the British took measures during the embarkation of the Acadians to the transport ships, some families became split up.

After 1758, thousands were transported to France. Most of the Acadians who later went to Louisiana sailed there from France on five Spanish ships. These had been provided by the Spanish Crown, which was eager to populate their Louisiana colony with Catholic settlers who might provide farmers to supply the needs of New Orleans residents. The Spanish had hired agents to seek out the dispossessed Acadians in Brittany, and kept this effort secret in order to avoid angering the French King. These new arrivals from France joined the earlier wave expelled from Acadia, and gradually their descendants developed the Cajun population (which included multiracial unions and children) and culture. They continued to be attached to French culture and language, and Catholicism.

The Spanish offered the Acadians they had transported lowlands along the Mississippi River, in order to block British expansion from the East. Some would have preferred Western Louisiana, where many of their families and friends had settled. In addition, that land was more suitable to mixed crops of agriculture. Rebels among them marched to New Orleans and ousted the Spanish governor. The Spanish later sent infantry from other colonies to put down the rebellion and execute the leaders. After the rebellion in December 1769, the Spanish Governor O'Reilly permitted the Acadians who had settled across the river from Natchez to resettle along the Iberville or Amite rivers closer to New Orleans.[18]

The British conducted a second and smaller expulsion of Acadians after taking control of the North Shore of what is now New Brunswick. After the fall of Quebec and defeat of the French, the British lost interest in such relocations. Many Acadians gradually returned to British North America, settling in coastal villages that were not occupied by colonists from New England. A few of the Acadians in this area had evaded the British for several years but the brutal winter weather eventually forced them to surrender. Some returnees settled in the region of Fort Sainte-Anne, now Fredericton, but were later displaced when the Crown awarded land grants to numerous United Empire Loyalists from the Thirteen Colonies after the victory of the United States in the American Revolution.

In 2003, at the request of Acadian representatives, Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada issued a Royal Proclamation acknowledging the deportation. She established July 28 as an annual day of commemoration, beginning in 2005. The day is called the "Great Upheaval" on some English-language calendars.

Geography

The Acadian descendants today live predominantly in the Canadian Maritime provinces, as well as parts of Quebec, Canada, and in Louisiana and Maine, United States. In New Brunswick, Acadians inhabit the northern and eastern shores of New Brunswick, from Miscou Island (French: Île Miscou) Île Lamèque including Caraquet in the center, to Neguac in the southern part, Grande-Anse in the eastern part and Campbellton through to Saint-Quentin in the northern part. Other groups of Acadians can be found in the Magdalen Islands and throughout other parts of Quebec. Many ethnic Acadian descendants still live in and around the area of Madawaska, Maine, where some of the Acadians first landed and settled in what is now known as the St. John Valley. There are also Acadians in Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia, at Chéticamp, Isle Madame, and Clare. East and West Pubnico, located at the end of the province, are the oldest regions that are predominantly ethnic Acadian.

Other ethnic Acadians can be found in the southern and eastern regions of New Brunswick, Western Newfoundland and in New England. Many of these latter communities have assimilated to varying degrees into the majority culture of English speakers. For many families in predominantly Anglophone communities, French-language attrition has occurred, particularly in younger generations.

The Acadians who settled in Louisiana after 1764 became known as Cajuns for the culture they developed. They have had a dominant cultural influence in many parishes, particularly in the southwestern area of the state, which is known as Acadiana.

Culture

Today Acadians are a vibrant minority, particularly in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Canada, and in Louisiana (Cajuns) and northern Maine, United States. Since 1994, Le Congrès Mondial Acadien has worked as an organization to unite this disparate communities and help preserve the culture.

In 1881, Acadians at the First Acadian National Convention, held in Memramcook, New Brunswick, designated August 15, the Christian feast of the Assumption of Mary, as the national feast day of their community. On that day, the Acadians celebrate by having a tintamarre, a big parade and procession for which people dress up with the colors of Acadia and make a lot of noise and music.

The national anthem of the Acadians is "Ave Maris Stella", adopted in 1884 at Miscouche, Prince Edward Island. The anthem was revised at the 1992 meeting of the Société Nationale de l'Acadie. The second, third and fourth verses were translated into French, with the first and last kept in the original Latin.

The Federation des Associations de Familles Acadiennes of New Brunswick and the Société Saint-Thomas d'Aquin of Prince Edward Island have resolved to commemorate December 13 annually as "Acadian Remembrance Day," in memory of the sinking of the Duke William and of the nearly 2000 Acadians deported from Ile-Saint Jean who died in 1758 while being deported across the North Atlantic: from hunger, disease and drowning.[19] The event has been commemorated annually since 2004; participants mark the day by wearing a black star.

Representation in other media

- In the 21st century, cartoons and animated films have been produced that feature Acadian characters. In addition there is a TV show named Acadieman.

Legacy of The Expulsion

- American writer Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published Evangeline, an epic poem loosely based on the 1755 deportation. The poem became an American classic. Activists used it as a catalyst in reviving a distinct Acadian identity in both Maritime Canada and in Louisiana.

- In the early 20th century, two statues were made of the fictional figure of "Evangeline" to commemorate the Expulsion: one was installed in St. Martinville, Louisiana and the other in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia.

- Canadian musician Robbie Robertson wrote a popular song based on the Acadian Expulsion, entitled "Acadian Driftwood". It was a track on The Band's 1975 album, Northern Lights – Southern Cross.

- Antonine Maillet's novel Pélagie-la-charette concerns the return voyage to Acadia of several deported families, starting 15 years after the Great Expulsion.

- The Acadian Memorial (Monument Acadien) has an eternal flame;[20] it honors the 3,000 Acadians who settled in Louisiana after the Expulsion.

- Monuments to the Acadian Expulsion gave been erected at several sites in the Maritime Provinces, such as at Georges Island, Nova Scotia, and at Beaubears Island.

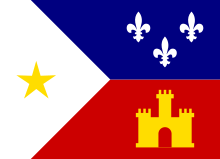

Flags

The flag of the Acadians is the French tricolour, with the addition of a golden star in the blue field (see above). This symbolizes Saint Mary, Our Lady of the Assumption, patron saint of the Acadians and widely known as the "Star of the Sea". This flag was adopted in 1884 at the Second Acadian National Convention, held in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island.

Acadians in the diaspora have adopted other symbols. The flag of Acadians in Louisiana, known as Cajuns, was designed by Thomas J. Arceneaux of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. In 1974 it was adopted by the Louisiana legislature as the official emblem of the Acadiana region. The state has supported the culture, in part because it has attracted cultural and heritage tourism.[21]

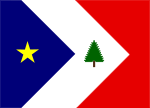

In 2004 New England Acadians, who were attending Le Congrès Mondial Acadien in Nova Scotia, endorsed a design by William Cork for a New England Acadian flag.[22] They have advocated for its wider acceptance.

Prominent Acadians

- Noël Doiron (1684–1758). A regional leader, Noel was among the more than 350 Acadians who died during the deportation when the Duke William sank on December 13, 1758.[23] He was widely celebrated and places have been named for him in Nova Scotia.

- Joseph Broussard, an Acadian folk hero and militia leader who joined French priest Jean-Louis Le Loutre in resisting the British occupation of Acadia.

Contemporary Canadian figures

- Angèle Arsenault, singer

- Aubin-Edmond Arsenault, the first Acadian premier of any province and the first Acadian appointed to a provincial supreme court

- Joseph-Octave Arsenault, the first Acadian appointed to the Canadian Senate from Prince Edward Island

- Jean-François Breau, singer

- Édith Butler, singer

- Phil Comeau, film director

- Rheal Cormier, baseball pitcher

- Julie Doiron, singer/songwriter

- Lyse Doucet, BBC journalist and presenter

- Yvon Durelle, boxer

- Jacques LeBlanc, boxer

- Roméo LeBlanc, former Governor General of Canada

- Phoebe Legere, artist

- Louis Robichaud, former New Brunswick premier, modernized education and the government of New Brunswick in the mid-20th century.

- Peter John Veniot, first Acadian to serve as Premier of New Brunswick

Figures in the US

- William Arceneaux, Louisiana historian and President of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) .

- Beyoncé, US singer, has some Acadian ancestry

- Solange Knowles, US singer, has some Acadian ancestry.

- Dudley J. LeBlanc, US Senator from Louisiana

- Zachary Richard, singer/songwriter from Louisiana

- John Pinette, stand-up comedian, actor and Broadway performer

See also

- List of Acadians

- History of Nova Scotia

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of the Acadians

- Acadian cuisine

Notes

- For information on Acadians who also have Indigenous ancestry, see:

- Parmenter, John; Robison, Mark Power (April 2007). "The Perils and Possibilities of Wartime Neutrality on the Edges of Empire: Iroquois and Acadians between the French and British in North America, 1744–1760". Diplomatic History. 31 (2): 182. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2007.00611.x.

- Faragher (2005), pp. 35-48, 146-67, 179-81, 203, 271-77

- Paul, Daniel N. (2006). We Were Not the Savages: Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations (3rd ed.). Fernwood. pp. 38–67, 86, 97–104. ISBN 978-1-55266-209-0.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2004). An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 23–39, 70–98, 111–14, 122–38. ISBN 978-0-8122-1869-5.

- Robison, Mark Power (2000). Maritime frontiers: The evolution of empire in Nova Scotia, 1713-1758 (PhD). University of Colorado at Boulder. pp. 53–84.

- Wicken, Bill (Autumn 1995). "26 August 1726: A Case Study in Mi'kmaq-New England Relationships in the Early 18th Century". Acadiensis. XXIII (1): 20–21.

- Wicken, William (1998). "Re-examining Mi'kmaq–Acadian Relations, 1635–1755". In Sylvie Depatie; Catherine Desbarats; Danielle Gauvreau; et al. (eds.). Vingt Ans Apres: Habitants et Marchands [Twenty Years After: Inhabitants and Merchants] (in French). McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 93–114. ISBN 978-0-7735-6702-3. JSTOR j.ctt812wj.

- Morris, Charles. A Brief Survey of Nova Scotia. Woolwich: The Royal Artillery Regimental Library.

The people are tall and well proportioned, they delight much in wearing long hair, they are of dark complexion, in general, and somewhat of the mixture of Indians; but there are some of a light complexion. They retain the language and customs of their neighbours the French, with a mixed affectation of the native Indians, and imitate them in their haunting and wild tones in their merriment; they are naturally full cheer and merry, subtle, speak and promise fair,...

- Bell, Winthrop Pickard (1961). The Foreign Protestants and the Settlement of Nova Scotia: The History of a Piece of Arrested British Colonial Policy in the Eighteenth Century. University of Toronto Press. p. 405.

Many of the Acadians and Mi'kmaq people were mixed bloods, foreign aboriginals or métis example, when Shirley put a bounty on the Mi'kmaq people during King George's War, the Acadians appealed in anxiety to Mascarene because of the "great number of Mulattoes amongst them".

Citations

- "Canadian census, ethnic data". Retrieved 18 March 2013.

A note on interpretation: With regard to census data, rather than going by ethnic identification, some would define an Acadian as a native French-speaking person living in the Maritime provinces of Canada. According to the same 2006 census, the population was 205,400 in New Brunswick; 34,025 in Nova Scotia; 32,950 in Quebec; and 5,665 in Prince Edward Island

- "Detailed Mother Tongue, Canada– Île-du-Prince-Édouard". Archived from the original on July 25, 2009.

- "File not found - Fichier non trouvé". statcan.ca. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Pritchard, James (2004). In Search of Empire: The French in the Americas, 1670-1730. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-82742-3.

Abbé Pierre Maillard claimed that racial intermixing had proceeded so far by 1753 that in fifty years it would be impossible to distinguish Amerindian from French in Acadia.

- Landry, Nicolas; Lang, Nicole (2001). Histoire de l'Acadie. Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 978-2-89448-177-6.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- Lockerby, Earle (Spring 1998). "The Deportation of the Acadians from Ile St.-Jean, 1758". Acadiensis. XXVII (2): 45–94. JSTOR 30303223.

- John Faragher. Great and Noble Scheme, 2005.

- Han, Eunjung; Carbonetto, Peter; Curtis, Ross E.; Wang, Yong; Granka, Julie M.; Byrnes, Jake; Noto, Keith; Kermany, Amir R.; Myres, Natalie M. (2017-02-07). "Clustering of 770,000 genomes reveals post-colonial population structure of North America". Nature Communications. 8: 14238. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814238H. doi:10.1038/ncomms14238. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5309710. PMID 28169989.

- The Oxford companion to Canadian history. Hallowell, Gerald. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0195415599. OCLC 54971866.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Parkman, Francis (1914) [1884]. Montcalm and Wolfe. France and England in North America. Little, Brown.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8566-8.

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749–61: A Study in Political Interaction". In Buckner, Phillip Alfred; Campbell, Gail Grace; Frank, David (eds.). The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation. pp. 105–106.

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm.

- Faragher (2005), pp. 110–112.

- For the best account of Acadian armed resistance to the British, see Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008.

- Reid, John G. (2009). Nova Scotia: A Pocket History. Fernwood. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-55266-325-7.

- Holmes, Jack D.L. (1970). A Guide to Spanish Louisiana, 1762-1806. A. F. Laborde. p. 5.

- Pioneer Journal, Summerside, Prince Edward Island, 9 December 2009.

- "Acadian Memorial - The Eternal Flame". Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Acadian Flag". Acadian-Cajun.com. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- "A New England Acadian Flag". Archived from the original on 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- Scott, Shawn; Scott, Tod (2008). "Noel Doiron and East Hants Acadians". The Journal of Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. 11: 45.

General references

- Dupont, Jean-Claude (1977). Héritage d'Acadie (in French). Montreal: Éditions Leméac.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-24243-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frink, Tim (1999). New Brunswick, A Short History (2nd ed.). Summerville, New Brunswick: Stonington Books. ISBN 978-0-9682-5001-3.

- Scott, Michaud. "History of the Madawaska Acadians". Retrieved 2008-03-05..

- Mosher, Howard Frank (1997). North Country: A Personal Journey Through the Borderland. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-39124-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Chetro-Szivos, J. Talking Acadian: Work, Communication, and Culture, YBK 2006, New York ISBN 0-9764359-6-9.

- Griffiths, Naomi. From Migrant to Acadian: a North American border people, 1604–1755, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005.

- Hodson, Christopher. The Acadian Diaspora: An Eighteenth-Century History (Oxford University Press; 2012) 260 pages online review by Kenneth Banks

- Jobb, Dean. The Acadians: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph, John Wiley & Sons, 2005 (published in the United States as The Cajuns: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph)

- Kennedy, Gregory M.W. Something of a Peasant Paradise? Comparing Rural Societies in Acadie and the Loudunais, 1604-1755 (MQUP 2014)

- Laxer, James. The Acadians: In Search of a Homeland, Doubleday Canada, October 2006 ISBN 0-385-66108-8.

- Le Bouthillier, Claude, Phantom Ship, XYZ editors, 1994, ISBN 978-1-894852-09-8

- Magord, André, The Quest for Autonomy in Acadia (Bruxelles etc., Peter Lang, 2008) (Études Canadiennes - Canadian Studies 18).

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (1969). The Acadian Deportation: Deliberate Perfidy Or Cruel Necessity?. Copp Clark.

- Runte, Hans R. (1997). Writing Acadia: The Emergence of Acadian Literature 1970–1990. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-0237-1.

- Deveaux Cohoon, Cassie (2013). Jeanne Dugas of Acadia. Cape Breton University Press. ISBN 978-1-897009-71-0.

External links

- Thematic project on the Acadians at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- 1755: The History and the Stories

- Acadian-Cajun History & Genealogy – Acadian-Cajun culture, history, & genealogy.

- Acadian.org - Oldest Acadian history and genealogy website

- Musee acadien and Research Centre of West Pubnico

- Jean Pitre circa 1635

- Acadians of Madawaska, Maine

- Quit rents paid by Acadians (1743–53)