White-winged dove

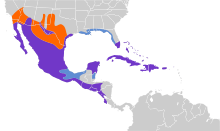

The white-winged dove (Zenaida asiatica) is a dove whose native range extends from the south-western United States through Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

| White-winged dove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Perching on a saguaro cactus in Tucson, Arizona | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Genus: | Zenaida |

| Species: | Z. asiatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Zenaida asiatica | |

| |

| Purple : Year-round Orange : Breeding Blue : Nonbreeding | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy and systematics

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram showing the position of the white-winged dove in the genus Zenaida.[2] |

The white winged dove is one of fourteen dove species found in North America north of Mexico.[3] The Zenaida doves evolved in South America, and then dispersed into Central and North America.[4]

The English naturalist George Edwards included an illustration and a description of the white-winged dove in his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds which was published in 1743.[5] The dove was also briefly described by the Irish physician Patrick Browne in 1756 in his The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica.[6] When in 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the tenth edition, he placed the white-winged dove with all the other pigeons in the genus Columba. Linnaeus included a brief description, coined the binomial name Columba asiatica and cited the earlier authors.[7] The type locality is Jamaica.[8] The dove is now placed in the genus Zenaida that was introduced in 1838 by the French naturalist Charles Lucien Bonaparte.[9][10]

The West Peruvian dove used to be considered part of the white-winged dove species, but was split off as its own species in 1997 – though together they form a superspecies.[4]

The genus Zenaida was named for Zénaïde Laetitia Julie Princesse Bonaparte, the wife of Charles Lucien Bonaparte.[11]:414 The specific epithet asiatica means Asiatic, likely meant in reference to the Indies. The naming is erroneous however, as a mistake of translation. It was intended to refer to Jamaica – in the West Indies – not the Indian subcontinent and its East Indies.[11]:57

Subspecies

Three subspecies are recognised:[10]

- Z. a. asiatica (Linnaeus, 1758) – The nominate subspecies, its breeding range is in the southern US to Nicaragua and the West Indies.[4]

- Z. a. australis (Peters, 1913) – The breeding range is in western Costa Rica and western Panama. It is smaller than the nominate subspecies, with browner back and wings, and a more red colored chest. It includes former subspecies Z. a. panamensis.[4] Australis means "southern" in Latin.[11]:62-63

- Z. a. mearnsi (Ridgway, 1915) – The breeding range encompasses the southwestern US, western Mexico, including Baja California. It is larger, paler, and grayer than the nominate subspecies. This subspecies includes the former subspecies Z. a. clara, Z. a. grandis, Z. a. insularis, and Z. a. palustris.[4] It is named after Lt. Col. Edgar Alexander Mearns, an American ornithologist, army surgeon, and bird collector throughout the Americas and Africa.[11]:244

Though they are highly variable, some general trends in characteristics may be made based on geography. Eastern birds tend to be paler and grayer, and southern birds tend to be browner and darker. Birds in central Mexico and Texas are the largest, whereas birds in southern Mexico, lower Central America, the Yucatán Peninsula are the smallest.[4]

Description

White-winged doves are a plump medium sized bird (large for a dove), at 29 cm (11 in) from tip to tail and a mass of 150 g (5.3 oz).[12] They are brownish-gray above and gray below, with a bold white wing patch that appears as a brilliant white crescent in flight and is also visible at rest. Adults have a patch of blue, featherless skin around each eye and a long, dark mark on the lower face. They have a blue eye ring and their legs and feet are brighter pink/red. Their eyes are bright crimson, except for juveniles who have brown eyes. Juveniles are duller and grayer than adults and lack iridescence. Juvenile plumage is usually found between March and October.[12]

Differentiating between sexes is difficult, and usually requires examination of the cloaca. Males do have a more iridescent purple color to the crown, neck and nape as well as a more distinctive ear spot, though the differences are slight. Males are usually heavier on average, but differences in daily weight due to feeding make this an inaccurate field tool. Thus most observers cannot accurately differentiate between sexes based on external characteristics alone.[13]

The identifying hallmark is its namesake white edged wing, which similar species lack. It appears similar to the mourning dove, with which it may be easily confused. Compared to the mourning dove, it is larger and heavier. It has a short rounded tail, whereas the mourning dove has a long, tapered triangular tail. The mourning dove has several black spots on the wing; the white winged dove does not.[12] Other similar species include the white-tipped dove, but the lack of white wing edging is distinctive. The same goes for the invasive Eurasian collared dove, which is further differentiated by grayish overall color and black neck band.[13]

Their molt is similar to that of the mourning dove. Molting runs June through November, and occurs in the summer breeding grounds unless interrupted by migration.[13]

Vocalizations

David Sibley describes the call as a hhhHEPEP pou poooo, likening it to the English phrase "who cooks for you". They also make a pep pair pooa paair pooa paair pooa call, with the last two words being repeated at length.[12] Males will set on dedicated perches to give their call, which is referred to as a "coo". Calling is most frequent during the breeding season, and peaks in May and June. Most calls are given just before dawn, or in the late afternoon. Females give a slightly softer and more slurred call than males. The purpose of calling is uncertain, but is mainly used for courtship and to defend territory. A shortened version of their song may be used between mates to maintain pair bonds. Nestlings can make noises starting at two days old; by five days old they can whistle a sur-ee call to beg for food.[4]

Non-vocal sounds include a wing whistle at take-off, which is similar to that of the mourning dove, albeit quieter. Their wing beats are heavy, sounding similar to other pigeons.[12] When leaving cooing perches, males make an exaggerated and noisy flapping of the wings.[4]

Distribution and habitat

Some populations of white-winged doves are migratory, wintering in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. They are year-round inhabitants in Texas. San Antonio, Texas, had a year-round population of over a million doves in 2001.[14] The white-winged dove inhabits scrub, woodlands, desert, urban, and cultivated areas.[4] They are found increasingly far north, now being visitors to most of the United States, and small parts of southern Canada.[12]

In recent years with increasing urbanization and backyard feeding, it has expanded throughout Texas, into Oklahoma, Louisiana and coastal Mississippi. It has also been introduced to Florida.[4] The white-winged dove is expanding outside its historic range into Kansas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and northern New Mexico. It has been increasingly reported as far north as Canada and Alaska.[15][16] Within Arizona, populations are effectively divided between agricultural and desert groups.[17] It shares its habitat with that of the mourning dove, but the white winged dove will fly higher.[12]

They generally nest at low densities in the desert, but are found in high concentrations near riparian areas. Nesting in riparian zones is referred to as colonial, as opposed to non-colonial behavior in more harsh environments.[3] Such colonies are quite variable, but may be very large. Colony size varies from 5 hectares (0.019 sq mi) to well over a 1,000 hectares (3.9 sq mi). Outside of colonies, nests have a density of less than 10 per hectare, but within colonies there are 500-1,000 nests per hectare.[18]

Before the advent of widespread agriculture, they may not have been widely present in what is now the United States – evidenced by a lack of fossil remains and absence from the journals of early European explorers. Their presence in California is likely recent, as a result of the manmade filling of the Salton Sea at the turn of the 20th century. The historical range of the dove closely mirrors that of the saguaro cactus, which it relies on heavily for nectar and fruit where it is found. Modern agriculture has greatly expanded their range by providing a reliable source of forage.[3] The urban heat island effect may also enable them to live further north than they otherwise could.[4]

White-winged doves typically migrate into Arizona beginning in March.[3] In California, birds arrive in April and depart by August. Texas migrations run from April through June, peaking in May, and departures run September to October.[4] Migratory groups may include as many as 4,000 individuals,[19] though typically less than 50. A combination of weather, food availability, and hunting pressure can affect the timing of migration.[4] As populations expand in Texas they are becoming less migratory; about 1/3 of birds now overwinter in Texas.[20] Migrations are tracked via traditional banding methods, but the isotope composition of hydrogen and carbon in the feathers can also be used. A 2015 study showed that by tracking the amount of various isotopes, researchers could accurately identify a white-winged doves migration origin. They could also identify if it had been eating from saguaros because of the unique carbon signature that cactus photosynthesis produces.[17]

Behavior and ecology

Flocks of up to a million birds have been recorded.[19]

Breeding and nesting

To impress females, males circle them with tail spread and wings raised. Males and females work together in raising the young. It builds a flimsy stick nest in a tree of any kind and lays two cream-colored to white, unmarked eggs. One chick often hatches earlier and stronger, and so will demand the most food from the parents. A dove may nest as soon as 2–3 months after leaving the nest, making use of summer heat. The dove will nest as long as there is food and enough warmth to keep fledglings warm. In Texas, they nest well into late August. Families and nestmates often stay together for life, perching and foraging together.

They have better nesting success when in mesquite or tamarix trees. Breeding occurs in two peaks in the summer, although the timing of their breeding varies among years. The peak breeding times for these desert doves occur from May-June to July-August. Breeding in urban areas also occurs in two peaks but may be somewhat offset in timing compared to the desert birds. By early September, most of the adult birds have already begun the migration south. The young leave soon after.[3]

Eggs are relatively small compared to bodyweight, as white-winged doves invest more energy in feeding altricial young instead of laying large eggs that would enable precocial young.[21]

They will return to the same nesting site year after year, sometimes rebuilding a nest in the exact location it was the year before.[18]

Males attend to the nest for the majority of the day, except for foraging breaks during the mid-morning and late afternoon while the female watches the nest. At night, females watch the nest, the male roosts nearby.[20]

Juvenile feathers begin to replace the natal down by seven days old. The prejuvenile molt is complete around 30 days old.[13]

Feeding

White-winged doves are granivorous, feeding on a variety of seeds, grains, and fruits. Western white-winged doves (Zenaida asiatica mearnsii) migrate into the Sonoran Desert to breed during the hottest time of the year because they feed on pollen and nectar, and later on the fruits and seeds of the saguaro cactus. They also visit feeders, eating the food dropped on the ground. Unlike mourning doves, they corn and wheat right off the head.[4] This gregarious species can be an agricultural pest, descending on grain crops in large flocks.

White-winged doves have been found to practice collaborative feeding. Observations in Texas revealed that some bird were shaking seeds from a Chinese tallow tree for the benefit of those on the ground. Mourning doves may represent a vector to spread the invasive Chinese tallow tree, by defecating undigested seeds.[22]

Agricultural fields, especially cereal grains, are a major source of forage. However, they provide less nutrition and protein content, which limit productivity. Having access to significant amounts of native seed is important to ensure that nestlings fledge and are healthier. This is made even more critical by the fact that white-winged doves do not supplement their diet with insects while raising young, unlike many other grain eating birds.[21]

Survival

White-winged doves are subjected to the usual arid-land predators, including foxes, bobcats, snakes, and coyotes. Aerial predators include owls and hawks. Domestic cats and dogs also take doves.[15]

The oldest recorded wild individual lived to 21 years and 9 months, though the average lifespan is closer to 10 or 15 years. In captivity they have been recorded to live up to 25 years.[15]

In culture

White-winged doves are popular as game-birds for hunting. They are the only North American game species that is also a migratory pollinator.[23] Hunting of the species peaked in the late 1960's, with an annual take of about 740,000 birds in Arizona. That has since fallen; in 2008 just under 80,000 birds were taken in Arizona. However the national take is larger, 1.6 million were hunted in 2011, with Texas representing the lions share at 1.3 million. A majority of the hunted birds are juveniles, averaging about 63% of the catch. Large numbers of birds were taken prior to the 1970's, when falling populations led a tightening of hunting laws. In the 1960's, hunters could legally take up to 25 birds per day in Arizona over a three week season. The Arizona dove season has since been restricted to two weeks and six birds per day, with shooting only allowed for half of each day.[3] The bag limit in Texas is four birds per day, but the Texas catch remains the largest of any state.[24]

They are also popular among birders and photographers. People in many areas provide feeding stations and water in backyards to attract them for observation.[3]

The Stevie Nicks song Edge of Seventeen features a white-winged dove.[15]

Status

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has tracked the population of the mourning dove for decades. The United States population peaked in 1968, but fell precipitously in the 1970's. The decline is likely due to loss of large nesting colonies in the 1960’s and 1970’s from habitat destruction, shifts in agricultural trends, and over-hunting. The population has continued to decline despite tougher hunting laws. Its population and range in Arizona has sharply contracted, though its range continues to expand in Texas. Even though it is the second most shot-hunted bird in the United States, it remains poorly studied, especially in California, Florida, as well as in Mexico.[3][24]

Lead poisoning, especially in hunting areas, poses a significant risk to white-winged dove health. A 2010 Texas study found that 66% of doves had elevated lead levels. The study noted that birds with lethal concentrations of lead were not found because accidental ingestion of lead shot can kill birds in just two days, and that they are incapacitated before that point, meaning that such birds died before they could be collected by researchers.[25]

Climate change is expected to expand their range to the north, but will also threaten populations with increased drought and fire, which destroy habitat, and spring heatwaves which can kill young in the nest.[26]

Colonial nesting sites in Mexico have seen significant losses. The main causes were brush clearing to make way for agricultural or urban development (leading to habitat loss), extreme weather such as droughts and hurricanes, and over-hunting. The population in Mexico followed the trend of American populations. In the 1970's, there were only a million birds in northeastern Mexico, compared to a rebound of 16 million in the 1980's, and five million in 2007. Habitat fragmentation is of great concern to the species, especially due to the preference for returning to the same large colonies year after year. Due to continued pressures, large nesting colonies are now mainly gone, and are not expected to return. Despite this, the white-winged dove has proved adaptable to human disturbance, and is regarded as a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[1][18]

Gallery

Showing off a slightly more purpleish color

Showing off a slightly more purpleish color.jpg) Closeup showing the distinctive red eye and blue eye ring

Closeup showing the distinctive red eye and blue eye ring

The white wing patch that edges the wings at rest becomes a stripe when the wing is extended

The white wing patch that edges the wings at rest becomes a stripe when the wing is extended.jpg) With squabs in Puerto Rico

With squabs in Puerto Rico Juvenile

Juvenile Composite identification image

Composite identification image.jpg) Eating from its favorite food, a saguaro fruit

Eating from its favorite food, a saguaro fruit

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Zenaida asiatica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banks, R.C.; Weckstein, J.D.; Remsen Jr, J.V.; Johnson, K.P. (2013). "Classification of a clade of New World doves (Columbidae: Zenaidini)". Zootaxa. 3669 (2): 184–188. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3669.2.11. PMID 26312335.

- Rabe, Michael J. (June 2009). Sanders, Todd A. (ed.). "Mourning Dove, White-winged Dove, and Band-tailed Pigeon: 2009 population status" (PDF). Laurel, Maryland: United States Fish and Wildlife Service. pp. 25–32.

- Schwertner, T. W.; Mathewson, H. A.; Roberson, J. A.; Waggerman, G.L. (March 4, 2020). Poole, A.F.; Gill, F. B. (eds.). "White-winged Dove - Zenaida asiatica - Birds of the World Online". birdsoftheworld.org. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Edwards, George (1743). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. London: Printed for the author, at the College of Physicians. p. 76, Plate 76.

- Browne, Patrick (1756). The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica. London: Printed for the author, and sold by T. Osborne and J. Shipton. p. 468.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae:Laurentii Salvii. p. 163.

- Peters, James Lee, ed. (1937). Check-List of Birds of the World. Volume 3. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 87.

- Bonaparte, Charles Lucian (1838). A Geographical and Comparative List of the Birds of Europe and North America. London: John Van Voorst. p. 41.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Pigeons". IOC World Bird List Version 10.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names (PDF). London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Sibley, David, 1961- (2014). The Sibley guide to birds. Scott & Nix (Firm) (Second ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-307-95790-0. OCLC 869807502.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fredricks, Timothy B.; Fedynich, Alan M.; Benn, Steve J. (June 2010). "Evaluation of a New Technique for Determining Sex of Adult White-Winged Doves (Zenaida asiatica)". The Southwestern Naturalist. 55 (2): 225–228. doi:10.1894/MH-35.1. ISSN 0038-4909.

- "White-winged Dove", Dept. of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences Texas A&M University, retrieved March 7, 2015

- "White-winged Dove Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- "Featured pollinators". US Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Carleton, Scott; Rio, Carlos; Robinson, Timothy (2015-08-01). "Feather isotope analysis reveals differential patterns of habitat and resource use in populations of white‐winged doves". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 79 (6): 948–956. doi:10.1002/jwmg.916.

- Johnson, Yara Sánchez; Hernández, Fidel; Hewitt, David G.; Redeker, Eric J.; Waggerman, Gary L.; Meléndez, Heriberto Ortega; Treviño, Héctor V. Zamora; Roberson, Jay A. (2009). "Status of White-Winged Dove Nesting Colonies in Tamaulipas, México". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 121 (2): 338–346. doi:10.1676/08-054.1. ISSN 1559-4491. JSTOR 20616905.

- "White-Winged Dove Fact Sheet". www.desertmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- Small, Michael F.; Taylor, Emariana S.; Baccus, John T.; Schaefer, Cynthia L.; Simpson, Thomas R.; Roberson, Jay A. (2007). "Nesting Home Range and Movements of an Urban White-Winged Dove Population". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 119 (3): 467–471. doi:10.1676/05-132.1. ISSN 1559-4491. JSTOR 20456034.

- Pruitt, Kenneth D.; Hewitt, David G.; Silvy, Nova J.; Benn, Steve (2008). "Importance of Native Seeds in White-Winged Dove Diets Dominated by Agricultural Grains". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 72 (2): 433–439. doi:10.2193/2006-436. ISSN 0022-541X. JSTOR 25097558.

- Colson, William; Fedynich, Alan (June 2016). "Observations of unusual feeding behavior of white-winged dove on Chinese tallow". The Southwestern Naturalist. 61 (2): 133–135. doi:10.1894/0038-4909-61.2.133. ISSN 0038-4909.

- "White-winged Dove". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- Collier, Bret A.; Kremer, Shelly R.; Mason, Corey D.; Peterson, Markus J.; Calhoun, Kirby W. (2012). "Survival, fidelity, and recovery rates of white-winged doves in Texas". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 76 (6): 1129–1134. doi:10.1002/jwmg.371. ISSN 1937-2817.

- Fedynich, Alan M.; Fredricks, Timothy B.; Benn, Steve (2010-09-01). "Lead Concentrations of White-winged Doves, Zenaida asiatica L., Collected in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, USA". Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 85 (3): 344–347. doi:10.1007/s00128-010-0072-3. ISSN 1432-0800. PMID 20686750.

- "White-winged Dove". Audubon. 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- Kelling, Steve. "Cornell Lab of Ornithology". What we’re learning: Dynamic Dove Expansions: Citizen Science illustrates the spectacular range expansions taking place throughout North America. Audubon Conservation. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- "National Geographic" Field Guide to the Birds of North America ISBN 0-7922-6877-6

- Handbook of the Birds of the World Vol 4, Josep del Hoyo editor, ISBN 84-87334-22-9

- "National Audubon Society" The Sibley Guide to Birds, by David Allen Sibley, ISBN 0-679-45122-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zenaida asiatica. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Zenaida asiatica |

- White-winged Dove Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- White-winged Dove - Zenaida asiatica - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Stamps (for Belize, Cayman Islands, Honduras, Mexico, and United States) at bird-stamps.org

- White-winged dove photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- "White-winged dove media". Internet Bird Collection.

- White-winged dove videos at Tree of Life

- White-winged dove species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Interactive range map of Zenaida asiatica at IUCN Red List maps

- White-winged Dove Journal Natures World